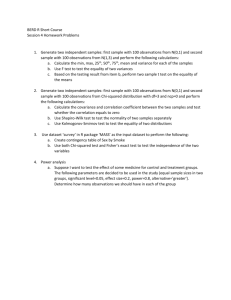

Women`s condition

advertisement