Non-fiction Sample #2 Research Paper When Victoria Claflin

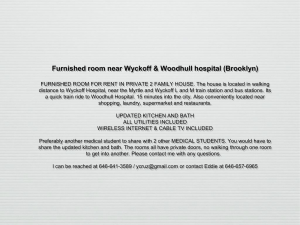

advertisement

Non-fiction Sample #2 Research Paper When Victoria Claflin Woodhull was just fourteen years old, she began to work as a clairvoyant. Her drunk, criminal father Buck, trying to increase her confidence in this money-making venture he designed, wrote Woodhull an unknowingly “prophetic rhyme that read, ‘Girl your worth has never yet been known, but to the world it shall be shown’” (Gabriel 11). Of course, Buck was merely thinking of his exploitation of his daughter – he could have no idea as to the social and political ramifications of his statement, as the basis of a revolution his own daughter would herself champion. In the mid-19th century, American society and government still did not recognize woman’s worth; her political, economic, social, and educational rights were all denied her. But in the latter half of the century, a revolt among inspired women would seek to change this fact. These women were far ahead of their time, and could have only limited effect on their contemporaries. An antiquated society was not eager to accept the reforms these visionary ladies espoused, often outright rejecting them from regular civilization. Their successes were tragically slow to appear, some only showing their faces decades after the women who birthed them were dead. The lives of late 19th century feminists Victoria Claflin Woodhull, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Mary Edwards Walker were all characterized by their revolutionary ideas, their rejection by society, and their ultimate tragic triumph, proving that the expectations and values of American society are slow to change when prompted by pioneers. The late 19th century feminist Victoria Claflin Woodhull was shockingly ahead of her time in terms of her revolutionary ideas. Like many other women’s rights activists of her time, Woodhull advocated suffrage for women; however, she “believed the fight for equality started not in the voting booth but in the bedroom, where polite society refused to go” (Gabriel 39). Woodhull demanded not only political but sexual equality for women, an idea truly unheard of in respectable society. She attacked the traditional bias towards males by asking: ‘What man with sufficient ability and wealth to support a party is ever attacked on the score of his immorality or irreligion; in other words, for his drunkenness, blasphemy or licentiousness? These Non-fiction Sample #2 are his private life. To go behind a man’s hall-door is mean, cowardly, unfair opposition. This is the polemical code of honor between men. Why is a woman to be treated differently?’ (Gabriel 111-112) While Victorian society looked on in horror, Woodhull challenged every basic idea behind the relations between the sexes. Everything that had previously been taken for granted as a man’s “‘private life’” was brought to the forefront and shown for what it truly was – unfair (Gabriel 39). Fifty years before women achieved even the right to vote, Victoria Claflin Woodhull’s claims were certainly revolutionary, and thus largely ignored by her more respectable contemporaries. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was another women’s rights activist whose pioneering ideas shocked her society. She never seemed to give any thought to public opinion; she simply saw the wrongs against women, and what had to be done to end them. Stanton had a clear perception of these wrongs, and for this reason her beliefs were far-reaching and visionary. She saw women’s rights as “‘more than a demand for suffrage. … [It] is a question covering a whole range of woman’s needs and demands … including her work, her wages, her property, her education, her physical training, her social status, her political equalization, her marriage and her divorce’” (Griffith 140). The total elevation of women in all areas of life, as Stanton advocated, was revolutionary for her time, and rejected by most. But perhaps Stanton’s most rebellious and unorthodox ideas concerned religion, which she saw as simply another vehicle for the subjugation of women. She challenged the way established religion viewed women in her book The Woman’s Bible, as “‘an afterthought in creation, the origin of sin, cursed by God, marriage for her a condition of servitude, maternity a degradation, unfit to minister at the altar and in some churches even to sing in the choir,’” (Griffith 210). Religion being an ingrained part of American society in the 1800s, Stanton’s ideas were so novel as to completely expel her from the common fold. Traditional society was again unable to accept the prophetic ideas espoused by a woman like Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Non-fiction Sample #2 In addition, the doctor and feminist Mary Edwards Walker’s views on the condition of women were perceived as radical for her time. In an age in which women were expected to wear floor-length skirts and rib-cracking corsets, Walker charged “that the weight, length, and strictures of typical female dress were not only uncomfortable but unsanitary and unhealthy. She said women’s garments ‘shackled and enfeebled’ their wearers and threatened their very sanity” (Walker 59). She advocated the Bloomer outfit instead, which consisted of a mid-length skirt over harem-style pants. She continued to wear her reformist dress until she died, an act that caused her to be ostracized throughout her life and career. Walker took her revolutionary views on dress to new heights of feminism when she claimed that: ‘A husband has no more right to dictate about the cut of his wife's clothes, than has the wife to interfere with the husband's, and it is time that the barbarous idea of men assuming such prerogatives, were swept away, and the inherent right of woman to dress as she pleases established’ (Walker 60-61). Historically, men controlled women’s clothing choices; their length, style, and cut were all determined according to man’s fancies and desires. When Walker declared the opposite – that women should dress for themselves according to their wants and needs – she challenged an entire system of thinking. Mary Edwards Walker’s radical opposition to the ways of society was easily shelved by a reluctant America. Women like Woodhull, Stanton, and Walker were few but not alone in the late 19th century. Across America, women from all classes “surfaced to breathe the air of freedom and self-determination,” although “women were still ‘the submerged sex’” (Kennedy, Cohen, and Bailey 351). The seeds of rebellion were being planted, although the harvest was still far off. Events like the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls in 1848 and the creation of several women’s suffrage organizations in the following years served to instill powerful ideas in women who had previously accepted their inferior status. Among many women, “the battle cry” was “‘Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less’” – a radical change in opinion from the previous eras (Bolden 22). Most women Non-fiction Sample #2 of this time period did not demand reforms as far-reaching as did the aforementioned ladies; however, even the slightest plea for a new role of women was deemed revolutionary by 19th century society. According to Ellen Carol Dubois, a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles, “By demanding a permanent, public role for all women, suffragists began to demolish the absolute, sexually defined barrier marking the public world of men off from the private world of women ... a basic challenge to the entire sexual structure” (Stalcup 233). A demand for equality was a demand for revolution, an overturning of an entire sexual caste system. Women were suddenly proposing that the public world be open to all, regardless of sex, when sex had previously defined all societal roles since the beginnings of Western culture. These calls for change terrified stalwarts of tradition, and their bearers were not fully recognized for decades as a result. Victoria Claflin Woodhull felt society’s rejection for her radical beliefs deeper than many of her contemporaries. Men in the 19th century were largely afforded the right to do as they please; any missteps on their part were settled over drink, thrust under the rug, or chalked up to eccentricities. “But no such leniency was afforded a woman who dared leave her proper place in the domestic sphere to enter public life, no matter how good her intentions. She had to be free from taint. Victoria was not” (Gabriel 89). Woodhull’s morality had always been questionable – she ran a newspaper that frequently exposed lurid scandals, she lived with both her ex-husband and her husband, she was an avid spiritualist, and she was often accused of being a prostitute and drunk. Despite the fact that many men of her time got away with much worse, Woodhull was pushed to the fringes of society because of mere rumors and societal mores. She expressed her anger at this injustice when she declared: ‘Because I am a woman, and because I conscientiously hold opinions somewhat different from the self-selected orthodoxy which men find their profit in supporting; and because I think it my bounden duty and my absolute right to put forward my opinions and to advocate them with my whole strength, self-selected orthodoxy assails me, vilifies me, and endeavors to cover my life with ridicule and dishonor’ (Gabriel 110). Non-fiction Sample #2 Apparently the ridicule was too overwhelming for Woodhull, because she was soon pushed off the continent by public hatred. Her rejection still haunted her as a housewife in Britain though, which she made apparent when she yelled at a gardener who was straightening her paths, “‘Those weeds have the courage to grow in the path of man and you murdered them’” (Gabriel 297). This was Woodhull’s fatal error; she stepped into the well-trod “‘path of man’” and she was destroyed for it (Gabriel 297). As a result of her revolutionary ideas, society expelled Victoria Claflin Woodhull cruelly and completely. Elizabeth Cady Stanton also experienced rejection by society for her unorthodox views. As one of the first women to publicly suggest suffrage as a facet of the women’s movement, Stanton was familiar with the public’s scorn from the start. As she later wrote, “‘The few who insisted on the absolute right [to universal suffrage] stood firmly together under a steady fire of ridicule and reproach even from their lifelong friends most loved and honored’” (Griffith 142). Stanton’s ideas, being different from those established by traditional society, defined her to many. Her polarizing views on religion also set her apart from most Americans, even within the women’s rights movement she helped to create. Her fellow feminists discouraged her from writing her book The Woman’s Bible, as they thought it would make their cause look silly. When Stanton published her book despite the torrents of criticism, she separated herself from her heirs for good. Her dear friend Susan B. Anthony was accepted as the leader of the women’s movement, and Stanton was shut out completely. She expressed her bitterness at the situation when she wrote, “‘They have given Susan thousands of dollars, jewels, laces, silks, and satins and me, criticisms and denunciations for my radical ideas’” (Griffith 215). Even the women Stanton was fighting for and with were held back by the constraints of their time, and were unable to accept all of her visionary reforms. Thus, the ostracism of Elizabeth Cady Stanton demonstrates society’s indifference to pioneering ideas at their birth. Mary Edwards Walker was also a victim of her society’s wrath towards her visionary ideas, as well as solely towards her womanhood. As a physician, Walker was forced to endure horrible discrimination, just in order to practice. Female doctors in 19th century America were seen as “women Non-fiction Sample #2 who did not know their rightful, biblical place in society and who disrupted the social pattern by insisting on invading a domain that was historically exclusively male” (Walker 57). Walker was subject to these same unfair stereotypes when she applied for a post as a physician during the Civil War. She tried for a commission again and again, yet was always declined – until 1864 – due simply to her status as a woman. Her male peers often went so far as to declare, as a medical board did in early 1864, “‘that she had no more medical knowledge than an ordinary housewife,’” clearly betraying their own inadequacies more than Walker’s (Walker 133). Not only was Walker rejected from the scientific community; she also encountered an unwelcoming women’s rights community. Like both Woodhull and Stanton, Walker’s ideas about women’s rights extended beyond the vote and immediate economic concerns. “Eventually she became something of a pariah among the women's rights activists. Her aggressiveness and growing eccentricities, and her coupling the right-to-vote campaign with her dress reform mania, embarrassed the stalwarts” (Walker 181). Because Walker demanded more than the current norm, she faced ostracism and ridicule from her peers, both in the scientific populace and the women’s movement. Mary Edwards Walker serves as yet another example of a woman largely ignored by her time as a result of her unconventional ideas. This rejection of pioneering ideas about women’s rights was not uncommon in the late 19 th century. From legislative bodies to regular citizens, many Americans were shocked by the demands of the feminists. Their appeals were repeatedly struck down by congresses across the nation, like the 1867 New York Constitutional Convention, which: rejected suffrage because it was an innovation ‘so revolutionary and sweeping, so openly at war with a distribution of duties and functions between the sexes as venerable and pervading as government itself, and involving transformations so radical in social and domestic life’ (Stalcup 235-236). Non-fiction Sample #2 Americans were not yet willing to give up the sexual structure that was to them as important as “‘government itself,’” and certainly as old (Stalcup 236). For that reason, society was diametrically opposed to the pleas of the women’s rights activists. Guardians of respectability were also loud combatants of the women’s rights movement. “Pure-minded Americans sternly resisted these affronts to their moral principles,” the “affronts” being merely demands for basic human rights (Kennedy, Cohen, and Bailey 623). Many Americans saw women’s rights as something that was morally wrong, and as a result, it would be a long and difficult journey to change their minds. Despite the massive backlash against their movement, 19th century feminists did not stem their calls for justice. Instead, they “realized that if they were going to push for equality, they needed to ignore criticism and what was then considered acceptable social behavior … However, the ardent feminists discovered that many people felt women neither should nor could be equal to men” (ushistory.org). This discovery was made soon, and although it did not hold back the feminists, it certainly held back their society from accepting their reforms. The rejection of women’s rights was deeply ingrained in American culture, and would prove to be difficult to remove. In the face of unrestrained prejudice and hatred, Victoria Claflin Woodhull was still able to die in triumph. Woodhull always knew she was ahead of her time; she often referred to the prospect youth, who would “‘in after years bless Victoria Woodhull for daring to speak for their salvation’” (Gabriel 224). Although the blistering ridicule she was bombarded with on a daily basis hurt horribly, Woodhull never doubted that she was speaking the voice of the future. Upon her death, a local Reverend “delivered a brief tribute, saying that Victoria had been one of the ‘twice born, the people of genius, not always understood or appreciated as they should be by the more dull once born ... She was in advance of her time, and accordingly suffered persecution’” (Gabriel 301). Woodhull saw the flaws in her society that no one else yet could, and was thus shunned for making those tradition-shattering realizations. Even after she was forced to leave America by cause of her ostracism, she did not forget what she had endured, and how she overcame it. When she finally died after a long and full life, “she said she wanted simply to be Non-fiction Sample #2 remembered by a line from Kant: ‘You cannot understand a man’s work by what he has accomplished but by what he has overcome in accomplishing it’” (Gabriel 300). By this measure, Woodhull was put to rest a truly great woman; she overcame childhood poverty, an exploitative and crude family, male and moral prejudice, scathing newspapers, and an overwhelmingly hypocritical and antiquated society. In the end, Victoria Claflin Woodhull was able to die triumphant, knowing that she was above the society that had ridiculed her. Elizabeth Cady Stanton also was not held back in death by her society’s rejection. By the end of her life, she was completely expelled from the suffrage organization that she had helped to create; however, she did not truly feel rejected or shortchanged. In fact, she felt her expulsion freed her, for she was no longer held by anyone else’s expectations. She wrote, “‘I have outgrown the suffrage association, as the ultimate [sic] of human endeavor, and no longer belong in its fold with its limitations’” (Griffith 215). At her death, Stanton was at last able to write, say, and believe as she pleased – even as she was alone. For in truth, Stanton never cared if she was a lone voice against many. She believed that: ‘cautious, careful people always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing, never can bring about a reform. Those who are really in earnest must be willing to be anything or nothing in the world’s estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathy with despised and persecuted ideas and advocates, and bear the consequences’ (Griffith 141). In addition, Stanton always knew that however much her ideas were ridiculed, the fight was always worth it. “‘I never forget that we are sowing winter wheat, which the coming spring will see sprout, and other hands than ours will reap and enjoy,’” she wrote after a particularly difficult episode (Griffith 208). Her triumph was that she never lost her convictions, even when the public condemned them. She never forgot the women of the future for whom she fought. Although Elizabeth Cady Stanton did not live to see most of her reforms enacted, her work for women’s rights gave her a triumphant legacy. Non-fiction Sample #2 Mary Edwards Walker was also able to triumph over her tragic circumstances. In 1865, Walker was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Andrew Johnson for her brave service as a physician in the Civil War. She held this medal as her most prized possession, an earthly recognition of her strength and courage, even in the face of rude male opposition. However, in 1917, her Medal of Honor was stricken from the records. It was determined that Walker had not shown great bravery in battle, and was thus no longer eligible for the award. But she did not let this harsh blow defeat her. “When the army struck her medal from the rolls she simply refused to acknowledge the decision. Nor did she surrender her medal ... and the army wisely did not force the issue. She continued to wear her medal until her death” (Walker 199). Walker would not let her rejection by society destroy her faith in herself and her abilities. She did not care what the government’s opinion was; she knew what the medal meant to her, and it did not matter to her if it meant nothing in America’s eyes. Thankfully, her medal eventually did mean something to America’s eyes, though years after her death. In 1977, Walker’s Medal of Honor was restored, at last giving her the honor she deserved. The Senate Veterans Affairs Committee supported this action, writing to Ann Walker, one of Mary Edwards Walker’s descendants: ‘It’s clear your great-grand-aunt [Walker] was not only courageous during the term she served as a contract doctor in the Union Army, but also as an outspoken proponent of feminine rights. Both as a doctor and feminist, she was much ahead of her time and, as is usual, she was not regarded kindly by many of her contemporaries. Today she appears prophetic’ (Walker 204). Walker knew she was prophetic, and for that reason she never gave in to her criticism. By her death, she was able to take solace in her conviction that “‘It is the times which are behind me’” (Walker 206). Thus, Mary Edwards Walker was able to experience a tragic triumph over her society – even in death. The struggle for women’s rights in the 19th century was tragic for all women involved, even as some of their goals were eventually achieved. Carrie Chapman Catt, a prominent suffragist, recognized this element within the victory of the vote for women when she wrote: Non-fiction Sample #2 ‘To get the word male out of the Constitution cost the women of the country … years of pauseless campaigning, … It was a continuous, seemingly endless chain of activity. Young suffragists who helped forge the last links of that chain were not born when it began. Old suffragists were dead when it ended’ (Ward and Burns 218). Even one of the most basic of the women’s demands – the right to vote – was so difficult to achieve that it required entire lifetimes to be given. These women, like Woodhull, Stanton, and Walker, gave precious years and social status to push for a reform they knew was worth that and more. Although both Walker and Stanton were dead by the passage of the 19th Amendment, and Woodhull was in Britain, their conviction in the noble cause of women’s rights allowed them to be victorious even when they weren’t alive to see their success. Their triumph also lies in their ability to look above the walls of society and straight at the subjugation of women. As Ellen Carol Dubois writes, “the achievement of nineteenthcentury suffragists was that they identified, however haltingly, a fundamental transformation of the family and the new possibilities for women’s emancipation that this revealed” (Stalcup 238). These “new possibilities for women’s emancipation,” although not able to be realized during the lifetimes of the first wave of feminists, laid the foundation for the second wave of feminism, which would take up the torch of the first and carry it onward (Stalcup 238). This was the true tragic triumph of the 19 th century feminist; she recognized “that the goals of genuine equality would take more than a lifetime to achieve,” and yet she still made a start (Kennedy, Cohen, and Bailey 1023). She felt for all women, not just those of her own century. Her compassion knew no bounds, just as the prejudice of her society knew none as well. But with this awareness by their sides, the women’s activists were able to meet every attack with a knowing glance and a well-put, “‘Ridicule, ridicule. Blessed be ridicule’” (Collins 308). These pioneers were not quick to change their society, but recognizing that inevitability, they were able to lay the foundation for future triumphs, thus experiencing those triumphs themselves. Thus, women’s rights activists of the late 19th century such as Victoria Claflin Woodhull, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Mary Edwards Walker held similar lives in terms of their radical views, their Non-fiction Sample #2 ostracism from society, and their ultimate victory – proving that American societal mores and values are hard to change in the face of revolutionary ideas. All of these women saw the wrongs against their sex clearer than anyone else was able to, and their unorthodox views mirror that vision gap. Although their particular focuses differed – Woodhull for sexual equality, Stanton for religious equality, and Walker for dress equality – their ideas were all revolutionary and thus all rejected. In the late 1800s, American society was still stuck in the Victorian mindset regarding women’s rights and roles. History told them that women were valuable exclusively in the home, and neither deserved nor needed political or economic rights. America was limited by the expectations it had always known, and as a result new standards and ideals were difficult to instill. The voice of the past was strong, and when women like Woodhull, Stanton, and Walker challenged it, their voices could only be ignored by the masses. But as the decades passed, their voices mingled with those of their society until they could be no less than accepted. Their path was a long and difficult one, filled with scorn and rejection, and nowhere near finished during the lifetimes of the women who took the first steps. But eventually the worst wrongs were righted and change was achieved. Society began the journey – albeit in little steps – towards the future first imagined by women long gone.