How Did Speech Develop

advertisement

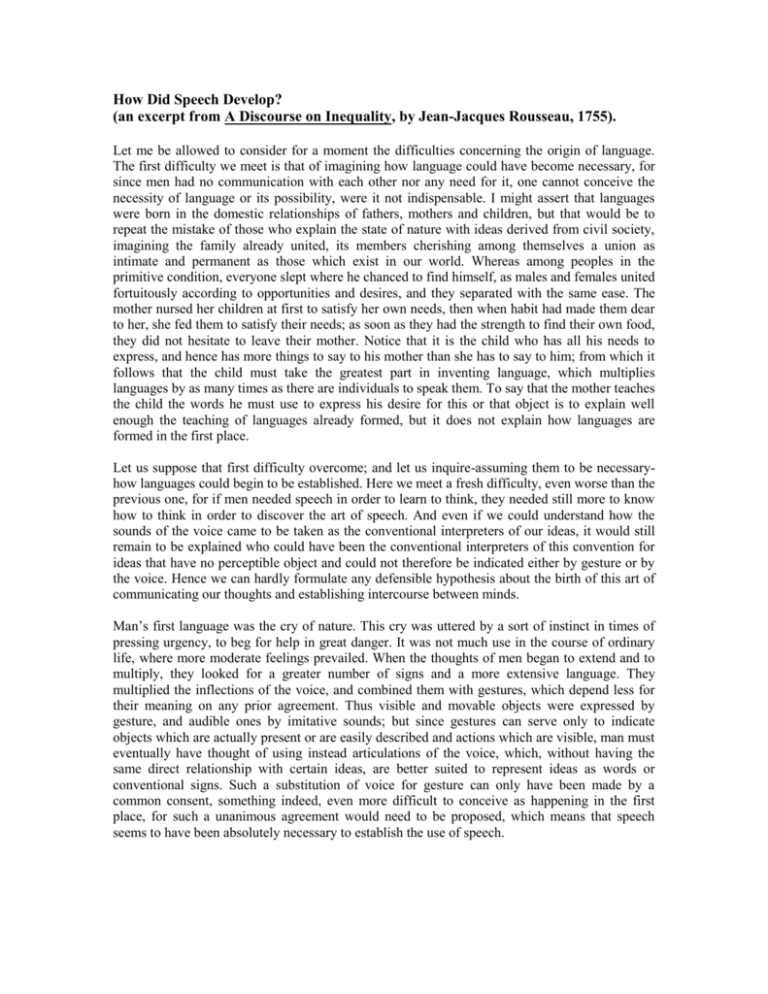

How Did Speech Develop? (an excerpt from A Discourse on Inequality, by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1755). Let me be allowed to consider for a moment the difficulties concerning the origin of language. The first difficulty we meet is that of imagining how language could have become necessary, for since men had no communication with each other nor any need for it, one cannot conceive the necessity of language or its possibility, were it not indispensable. I might assert that languages were born in the domestic relationships of fathers, mothers and children, but that would be to repeat the mistake of those who explain the state of nature with ideas derived from civil society, imagining the family already united, its members cherishing among themselves a union as intimate and permanent as those which exist in our world. Whereas among peoples in the primitive condition, everyone slept where he chanced to find himself, as males and females united fortuitously according to opportunities and desires, and they separated with the same ease. The mother nursed her children at first to satisfy her own needs, then when habit had made them dear to her, she fed them to satisfy their needs; as soon as they had the strength to find their own food, they did not hesitate to leave their mother. Notice that it is the child who has all his needs to express, and hence has more things to say to his mother than she has to say to him; from which it follows that the child must take the greatest part in inventing language, which multiplies languages by as many times as there are individuals to speak them. To say that the mother teaches the child the words he must use to express his desire for this or that object is to explain well enough the teaching of languages already formed, but it does not explain how languages are formed in the first place. Let us suppose that first difficulty overcome; and let us inquire-assuming them to be necessaryhow languages could begin to be established. Here we meet a fresh difficulty, even worse than the previous one, for if men needed speech in order to learn to think, they needed still more to know how to think in order to discover the art of speech. And even if we could understand how the sounds of the voice came to be taken as the conventional interpreters of our ideas, it would still remain to be explained who could have been the conventional interpreters of this convention for ideas that have no perceptible object and could not therefore be indicated either by gesture or by the voice. Hence we can hardly formulate any defensible hypothesis about the birth of this art of communicating our thoughts and establishing intercourse between minds. Man’s first language was the cry of nature. This cry was uttered by a sort of instinct in times of pressing urgency, to beg for help in great danger. It was not much use in the course of ordinary life, where more moderate feelings prevailed. When the thoughts of men began to extend and to multiply, they looked for a greater number of signs and a more extensive language. They multiplied the inflections of the voice, and combined them with gestures, which depend less for their meaning on any prior agreement. Thus visible and movable objects were expressed by gesture, and audible ones by imitative sounds; but since gestures can serve only to indicate objects which are actually present or are easily described and actions which are visible, man must eventually have thought of using instead articulations of the voice, which, without having the same direct relationship with certain ideas, are better suited to represent ideas as words or conventional signs. Such a substitution of voice for gesture can only have been made by a common consent, something indeed, even more difficult to conceive as happening in the first place, for such a unanimous agreement would need to be proposed, which means that speech seems to have been absolutely necessary to establish the use of speech. One must conclude that the first words men used had a much wider signification in their minds than do words employed in languages already formed. Each object was given at first a particular name, without regard to genus and species, which those first founders of language were incapable of distinguishing; and each individual thing presented itself in isolation to men’s minds as it did in the panorama of nature. If one oak was called A and another was called B (for the first idea one derives from observing two things is that they are not the same, and it often requires a great deal of time to discern what they have in common), it follows that the more limited the knowledge the more extensive the dictionary. The troublesomeness of all this nomenclature could not easily be relieved, for in order to arrange things under common and generic denominators, one must know their properties and the differences between them; one must have observations and definitions; that is to say, one must have more natural history and metaphysics than men of those times could possible have had. But when our new grammarians began-by what means I cannot conceive-to enlarge their ideas and to generalize their words, the ignorance of the inventors must have subjected this method to very narrow limitations; and just as they must at first have produced too great a multiplicity of nouns of individuals for lack of knowledge of genera and species, they must afterwards have produced too few genera and species for want of discriminating between the differences in things. To extend the analysis far enough would have needed more experience and more knowledge than they could have possessed. As for the most general concepts, they must have escaped their notice. How, for instance, would these men have imagined or understood the words ‘matter’, ‘mind’, ‘substance’, or ‘movement’, when the ideas which those words denote, being purely metaphysical, have no models to be found in nature? I shall stop with these first steps, and ask my critics to suspend their reading here in order to judge on the basis of the invention of the physical substantives, which is the easiest part of language to invent, how far language still had to go. I beg my critics to reflect how much time and knowledge must have been required for the discovery of numbers, abstract words, and all the tenses of verbs, particles, syntax, and the whole logic of language. For myself, alarmed as I am at the increasing difficulties, and convinced of the almost demonstrable impossibility that languages could have been created and established by purely human means, I leave to anyone who will undertake it, the discussion of the following difficult problem: Which was the more necessary, a society already established for the invention of language, or language already invented for the establishment of society? But whatever these origins may be, we see at least from the small pains which nature has taken to unite man through mutual needs or to facilitate the use of speech how little she has prepared their sociability. Indeed it is impossible to imagine why in the primitive state one man should have need of another or, to imagine what motive could induce the second man to supply it, and if so, how the two would agree between them the terms of the transaction. I know we are constantly being told that nothing is more miserable than man in the state of nature, but I would be pleased to have it explained to me what kind of misery can be that of a free being whose heart is at peace and whose body is in health? I ask which-civilized or natural life-is the more liable to become unbearable to those who experience it? 1. Think of the theory of sociobiology. What survival advantage could speech have given early humans?