Returning My Ticket: Supporting Dostoevsky`s Rejection of Religion

advertisement

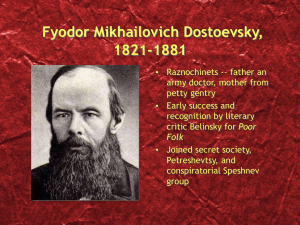

Winn 1 Julia Winn 2/21/2011 RELG2380 Returning My Ticket: Supporting Dostoevsky’s Rejection of Religion The moral critique of religion poses a great threat to religious belief. This critique suggests that religion makes humans behave intolerantly, support immoral social structures, undermine the moral law, and revere an immoral God. The fourth facet of this critique threatens religion the most, by questioning the morality of the very entity which religious believers hold above question. Dostoevsky, a 19th century Russian writer, argues this claim in the chapter “Rebellion” of his book The Brothers Karamazov. Dostoevsky’s moral critique of religion poses the greatest challenge to religious belief, because he uses undeniable logic and emotional appeals. Though theologian John Hick rebuffs this critique logically through his free will defense, Dostoevsky’s critique ultimately convinces more effectively. Dostoevsky employs both effective logical and emotional appeals in his critique to challenge religious belief. Dostoevsky’s argument begins by stating that innocent children suffer. Ivan, the character arguing against the morality of religion, provides numerous examples of suffering children. For example, Ivan retells a story about Turks who have been “torturing children, starting with cutting them out of their mothers’ wombs with a dagger”(Dostoevsky 238). These same Turks are described as tickling a baby so it laughs, and then shooting it in the face (Dostoevsky 239). Another disturbing example cited describes a Russian family who beat their five year old girl and locked her all night in an outhouse (Dostoevsky 242). Ivan’s final example describes an eight-year-old boy who accidently hurts a cruel general’s dog, and thus is punished by being ripped to pieces by the man’s dogs (Dostoevsky 243). These disturbing scenes serve as both an emotional hook and a logical introduction to Dostoevsky’s main point. The Winn 2 gruesome and vivid imagery of such examples capture the reader’s sympathy and horror for the innocent children. The emotional aspect of Dostoevsky’s critique carries a great deal of persuasive power, as it ensures an attentive reader. An argument without emotion lacks conviction, while an argument without logic lacks foundation. Thus, these descriptions of suffering also serve a logical purpose. They set the stage for the second claim of Dostoevsky’s critique of religion, and ultimately provide reason for his rejection of religion. Ivan cannot fathom why the suffering of innocent children needs to exists, if there is a moral God controlling the Earth. Dostoevsky uses apt analogies to convey this point and counter Christian responses. Christians say that evil or suffering of innocents is necessary to create harmony on earth. Ivan plays off this musical analogy, questioning: “if everyone must suffer, in order to buy eternal harmony with their suffering, pray tell me what have children got to do with it?”(Dostoevsky 244). He compares children to manure being used as fertilizer to richen the soil which is life (Dostoevsky 244). These two analogies demonstrate Dostoevsky’s refusal to accept that the well-being of the general population is worth the suffering of innocent children. By using analogies, Dostoevsky once again utilizes both logic and emotion. The analogies serve as examples for the point he is making, while also garnering the reader’s interest. Tangible examples in narrative form such as these convey a point much better than philosophical, speculative dialogue, because they help the reader easily draw comparisons between the claim and real life. Dostoevsky does not postulate on the sources of good and evil. Rather, he simply states direct cases of children suffering horrible events, and questions the necessity and worth of these events. Dostoevsky concludes that a God who allows such tragedy should not be followed. He does not deny the existence of a God, but rather he acknowledges and rejects such an immoral Winn 3 God. He ends his argument with a thought-provoking question. Ivan asks his brother Alyosha to “imagine that you yourself are building the edifice of human destiny…but for that you must…torture just one tiny creature….would you agree to be the architect on such conditions?” (Dostoevsky 245). Of course, Alyosha replies that he would not (Dostoevsky 245). Ending the argument in this way is highly effective, because Dostoevsky both causes one to consider one’s own response and logically concludes his argument. Most men would not create a structure for world harmony that requires the suffering and torture of innocent people, so why did God create such a system? This question implies that most humans are more moral than God. Assuming that moral behavior is the ultimate goal for humanity, we should seek to improve the world rather than compromising moral values for the general good. Any god who created such a flawed and immoral system which requires suffering of innocents does not deserve to be followed. John Hick provides the strongest response to the moral critique of religion in his free will defense, because he explains his case logically and appeals to our humanity. Hick states his case in three stages. The first stage upholds that God, though omnipotent, cannot create “selfcontradictions” (Hick 147). Hick uses concrete examples to explain this point. For example, God cannot create a round square, not because He isn’t all powerful, but because the concept of a round square does not fit the definition of a square (Hick 147). To elaborate his point, Hick uses the same logic on the example of a four-sided triangle, or “a horse that has none of the characteristics of a horse” (147). As justified previously, examples are most effective at capturing a reader’s attention and helping the reader draw connections between the argument and reality. The second stage of Hick’s argument flows logically from the first stage. Hick states that to create a being that is free to choose rightly but not wrongly would be a self-contradiction Winn 4 (148). Hick claims that in order to have a relationship with God, humans must have “the uncontrollable gift of freedom,” because otherwise we would just be puppets (148). The metaphor contrasting humans with puppets naturally appeals to our humanity, as we prefer to think we are free thinking beings, not controlled robots. This appeal captures the reader’s attention and causes one to speculate on one’s own free will. Hick saves his most emphatic message for last. In the third stage, he refutes the idea that God would possibly create humans who would only make the right choice. Hick says such creations would put God “in a relationship to His human creatures comparable with that of the hypnotist to his patient” (Hick 149). By using an analogy to clarify his point, Hick once again appeals to our humanity. The idea that our actions would be fake or arbitrary since we would only be able to choose the good opposes our preferred concept of freedom. Hick continues with his claim by stating that God wants “freely offered worship and obedience”(Hick 149). God would not be satisfied if He knew His creations had no options but to worship Him. Hick believes a world where humans only made the right choice would be “second-best to one in which created beings…come freely to love, trust and worship Him” (Hick 149). We referred to this idea in class as the Best Possible World; it states that suffering exists because God created humans to have free will in order to have the most authentic world. Ultimately, Dostoevsky’s side of the argument is stronger. I, like Dostoevsky, “return my ticket” and reject God (Dostoevsky 245). Dostoevsky, a professional writer, uses graphic imagery more persuasively. Though Hick persuasively argues that God wanted humans to have free will, our freedom does not justify taking away the freedom of innocent children like Dostoevsky depicts. Is the best possible world really one with situations such as Dostoevsky describes? Simply accepting that suffering must exist under God’s plan is a convenient response Winn 5 as it takes the responsibility to create change off our shoulders. An omniscient, omnipotent, just God could have created an entirely different, unfathomable system which would permit much less suffering. I believe Dostoevsky’s most shocking revelation—that most people are more moral than God—rings true. Like Dostoevsky claims, most humans would not create a system for the best possible world which would require the suffering of innocent children. Christians can claim all men suffer due to the poor choices of Adam and Eve during the creation, but babies are born pure and are sometimes harmed before they are given the chance to sin. The logic behind punishing someone before they commit a crime does not make sense. That would be comparable to expelling a student before he enters college under the assumption that he will cheat. Why accept a student into the school if only to expel him before giving them a chance? This final point is unavoidable. A God who created such a system must be immoral, and should be rejected. Though both authors have strong cases, Dostoevsky’s uses stronger emotions and tighter logic and thus prevails. I understand Hick’s view, but I believe that a God who created a system that not only allows, but requires, suffering such as genocide, rape, and torture of even the most innocent creatures, does not deserve to be worshipped or followed.