Dostoyevsky`s Notes From Underground

advertisement

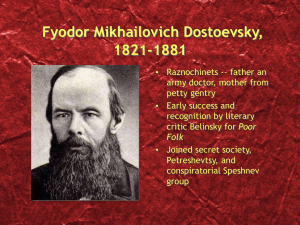

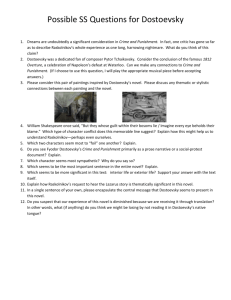

Notes From Underground Launchpad NEH Seminar – Existentialism – Summer 2014 Introduction It is perhaps no surprise that Fyodor Dostoevsky is known as one of the greatest psychological writers of all time given his own dramatic history of suffering. After being spared from the Tsar’s firing squad at the last minute, years in a Siberian gulag, and a life of plagued by epilepsy, he went on to write some of the great psychological and existential novels in all of World literature, including Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov. Notes from Underground, written in 1864, presents one of the first anti-heroes in European literature. By satirizing the rationalism and utopian sentiments of his time, the Russian novelist forces us to confront some of the more uncomfortable facts of human psychology. Dostoevsky’s antiutopianism ended up predicting many of the horrors caused by Twentieth Century efforts to systematically direct human behavior based on rational determinations of who we are and what is good for us. Dostoevsky’s novels never give us final answers to these questions, but show how the question of who we are cannot ever be answered with a simple formula. Historical Context While Notes from Underground can be seen as a critique of the progressive view of history and perfectibility in general, the text is also a direct satire of the Russian novel What Is To Be Done by Nikolai Chernyshevsky. In this novel, a poor, uneducated girl is saved from ruin by a series of enlightened benefactors. This girl, Vera, goes on to herself found a series of workshops where through enlightened benevolence, she is able to transform quite a few other poor women into educated entrepreneurs. The novel directly suggests that through enlightened self-interest, we would all arrive at the same conclusion: that working together in a spirit of harmony and openheartedness combined with scientific methods can lead to a total transformation of human society. Chernyshevsky states "...you know what the future will be. It's radiant and beautiful. Tell everyone that the future will be radiant and beautiful. Love it, strive for it, work for it, bring it nearer...to the extent that you succeed in doing so, your life will be bright and good, rich in joy and pleasure." Questions to Consider 1. Why would Dostoevsky satirize this seemingly beautiful view of the future? 2. What danger can a utopian view of humans and their future hold? 3. How do you think that the Chernyshevskian worldview relates to later Soviet and fascist ideologies? Existentialism and Dostoevsky Notes From Underground Launchpad NEH Seminar – Existentialism – Summer 2014 The movement, identified by Jean Paul Sartre as existentialism, has its roots in the nineteenth century in the works of such writers as Soren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Friedrich Nietzsche. As a novelist rather than an essayist, Dostoevsky’s relationship with the movement is more complex and ambivalent. While clearly preoccupied with such existentialist concerns as faith, death, meaning, the bureaucratization of society, and rational conceptions of humanity, Dostoevsky himself rejected the existentialist viewpoint and, as a member of the Russian Orthodox Church, identified faith as a resolution to existential angst. But his greatness as a writer enabled him to articulate the existentialist vision of the world in such a manner so as to make it persuasive and compelling. Summary In the opening lines, our unnamed narrator tells his audience “I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man.” So begins a novella that presents a disturbing theory of human psychology and a narration of the events that generated such a theory. In part one of the novella, the narrator engages the reader directly in describing his existential worldview, calls into question scientific claims that, as rational beings, humanity always follows self-interest. In opposition to these claims, the narrator declares that “We sometimes want pure rubbish precisely because in our own stupidity, we see this rubbish as the easiest path to the attainment of some preconceived profit” (p. 27)— In part two, Dostoevsky attempts to show what this existential worldview, translated into action, produces a life marked by cruelty and humiliation. Guiding Questions Part 1 – Pages 3-41 What theory of human psychology does our unnamed narrator criticize? What is his own theory of human psychology? How does Dostoevsky put forth this theory through the character of the unnamed narrator himself? What evidence does he give for his own theory? How does the unnamed narrator speak to your own experience? What is the relationship between vengeance and justice for the unnamed narrator? Why might “a man of perception” have difficulty respecting himself? Why does the unnamed narrator think pursuing self-interest threatens our freedom? Have you ever knowingly acted against your own self-interest? Why did you do so? Explain the metaphor of the piano key? Notes From Underground Launchpad NEH Seminar – Existentialism – Summer 2014 Are you like a piano key? Part 2 – Pages 42-130 Why would the narrator have imposed himself on a group of friends who do not welcome his presence? Why is the narrator so cruel to Liza? Why can’t he forgive Liza for hearing his confession about himself? What does the narrator mean when he says, “Excuse me, gentlemen, but I am not justifying myself with this allishness. As far as I myself am concerned, I have merely carried to an extreme in my life what you have not dared to carry even halfway, and what’s more, you’ve taken your cowardice for good sense, and found comfort in thus deceiving yourselves” (Peaver and Volokhonsky, 130)? How do you think episode in the narrator’s life led him to his ideas about human psychology, as expressed in part 1? REFERENCES: Chernyshevsky, Nikolai. What Is To Be Done?. Translated by Michael Katz. Cornell University Press. 1989. Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Notes from Underground. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Vintage Classics. 1994. Stephen Miller and Thomas Johnson