Notetaking Tool for Platos Republic

advertisement

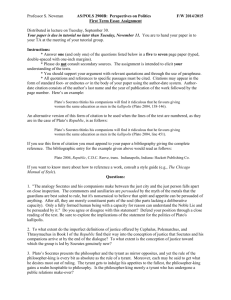

Notetaking Aid for Plato’s Republic Note to Instructors: Each section of the text (Following Jowett, Lee, and Bloom at different times and in no particular order) is present here. The demarcation of sections roughly follows Lee. The document is designed to ask questions that prompt discussion and is designed to be useful for leading online or seated discussions. Comments welcome at escobar@ecc.edu or fpegsl@rit.edu. Note to Students: This document is designed to promote a fuller understanding of Plato’s Republic. It is important to note that it will not replace your own reading and interpretation, but that it hopes to ask some of the questions that arise during the course of the text. Following the resource links should also be of assistance, but these should be supplements to the reading and not try to replace it. Still, this is a complex text and there is no shame in failing to understand portions of it. The thing is to try and plug away in a consistent and dedicated fashion. You can do this by taking notes on each section of the text, either as you read it or as you discuss it in a classroom setting. It is my hope that this will make you an active reader and force you to think through the relevant issues. The rest is up to you, however: no instrument can replace your own love of learning. Book and Section Questions Please begin by summarizing what you have read in these first few pages. Your summary should consist solely of your own words (plagiarism is punished with an immediate F in the course). Include the following elements in your summary: Book One 327-331 1. The discussants - briefly state who is speaking. 2. The plot. What happens in the first couple of pages? What is the setting? 3. The topic of discussion. 4. The arguments. Does anyone claim anything? If so, what do they claim and what reasons do they give for it? Make your response about 300 words. Please quote the text directly at least twice. When doing so, use Stephanus numbers to denote the source. Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Resources: Book One The Squashed Republic - an adumbrated version of the text Sparknotes - summary of major themes 1. What is the topic of this part of the text? 2. What does Polemarchus argue in these pages? 3. Who is doing the questioning and who is doing the answering? Does the Q&A nature of the dialogue establish any specific power dynamic? Who's in charge of the conversation during these five pages? Resources: 331-336 Book One 336b337e A Reader's Guide to the Republic: Summary of Polemarchus-Socrates Discussion Another Analysis of the Discussion An Explanation of Socratic Method 1. Who is speaking? 2. Who is Thrasymachus? Do some research to get a sense of the following: (a) the literal meaning of his name; (b) his role in the Republic. 3. What does Thrasymachus say about the method of argument and discussion that is taking place? What is his major point about it? 4. What challenge does he present to Socrates? 5. It is helpful to know that Thrasymachus is considered a sophist, and that this fact is related to his demand for payment in 337d. What is a sophist? 6. How does sophism relate to the educational system or systems to which you belong? Does the attack on sophism Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions translate also into an attack on modern education? If so, how or why? Resources: Book One 338a343d Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. 5 & 6 translated by Paul Shorey. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1969. 1. The discussion still concerns the correct definition of justice. What does it mean to say that justice is the interest of the stronger? 1. Note: make sure you understand the reference to "Polydamas the Pancratiast." Find out what Socrates means by this point (338c). 2. Note also the fuller definition/explanation of justice that Thrasymachus gives in 338e. 2. It has been said by the utilitarians (look up utilitarianism) that ethical correctness is defined by whatever maximizes happiness for all concerned. Here, Thrasymachus appears to be arguing explicitly that ethical correctness (justice) is whatever maximizes happiness for the ruling party of a society. Give a short argument for or against the position taken by either party. State the conclusion of the argument clearly and give two to three premises (reasons) in favor of the conclusion. 3. At 339c Socrates begins an attack on Thrasymachus' definition. Summarize the gist of the attack in one or two sentences. 1. Note that Polemarchus and Cleitophon break in at this point. Do they offer anything of value, or are they just parroting their leaders? Focus particularly on 340b. 2. At 340d Thrasymachus rejects the help that Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Cleitophon has tried to give him. Try to figure out what exactly is happening there. 4. Note the discussion around 341 and 342 of the true nature of a person who is practicing an art. Socrates speaks of pilots and physicians, for example. What is his overall point? Note that Socrates argues at one point that the arts "rule over" something. The art of medicine, we might say, "rules over" the body and thereby tries to strengthen it. We can imagine a doctor attending to someone's body, finding a weakness in it, and then attempting to eliminate the deficiency through the art of medicine. Socrates is trying to get Thrasymachus to accept this point over not just medicine, but all arts. In the end, then, he wants to extract the following admissions and promote the following argument: 1. Every art strives toward some excellence 2. All such excellences are for the sake of something other than the art - in other words, the art doesn't strive for anything other than to help make its subjects excellent. 3. If these things are true, then no art should ever strive for the sake of the gain of the artist. 4. And if #3 is true, then the art of ruling should not strive for the sake of the gain of the ruler. It stands to reason, claims Socrates, that the art of ruling is something we engage in solely for the sake of the excellence of the ruled. That, just as we try to improve horses by becoming horsemen, and just as we try to improve students by becoming teachers, we try to improve the people by becoming rulers. 5. But note the reaction by Thrasymachus on 343b. Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Is this a convincing response? Resources: Book One 343e-354 LitCharts: http://www.litcharts.com/lit/the-republic/book1. Contains a brief overview of each argument in Book One. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/callicles-thrasymachus/#3. Article on Callicles and Thrasymachus summarizing two different attacks on conventional morality that are presented (and refuted) in Plato's work. I've linked directly to the Thrasymachus v Socrates section, but the entire article is worthwhile. 1. Summarize the argument by Thrasymachus that the unjust man benefits more than the just man. 2. Give an argument of your own in favor of this argument or against. State your conclusion clearly and provide two to three premises (reasons) in support of the conclusion. 3. The argument by Thrasymachus can be summarized (and perhaps oversimplified) as the claim that justice is for suckers who don't mind working for the sake of others. In the point that he makes earlier about the ruler and the ruled, this amounts to justice being an attempt by the rulers to utilize a concept that the ruled will use to the rulers' advantage. So, when we (the ruled) act justly all we are doing is creating some benefit for the rulers. In effect, we are being suckers who fail to see that injustice is where we can gain something for ourselves. Therefore, we should not aim to be just - we should instead attempt to be unjust. This is why Thrasymachus is taken to be attacking "conventional morality" - most of us think that we should Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions try to be just, but in doing so we will end up harming ourselves and never fulfilling the high ideals of justice. Please comment on this line of thinking and apply it to a recent example of a law that you are being asked to obey. You will need to do appropriate research to answer this question if you are not the type to follow politics, so please supply the relevant citations and references. 4. Note that at 345c Socrates returns to the question of art, noting that Thrasymachus now appears to be arguing that a shepherd is in fact capable of being a shepherd while he thinks primarily of his own gain and not the gain of his sheep (the shepherd/sheep language is obvious a reference to the ruler and the ruled). Socrates charges that in this connection the shepherd is in fact not a shepherd at all (and to this point Thrasymachus appears to have already agreed), but instead is a moneymaker, with moneymaking being a separate art and not connected to the art of sheepherding or of ruling. At 346d Socrates appears to secure from Thrasymachus the admission that no one gains from the art which they practice unless they attach to it an art of money-making or wage-earning. 1. At this point I want you to think of this in light of "art" in the sense that you would consider that word today. Think of the art of making music (guitar) or painting (with oil, let's say). When you engage the art, do you engage it for the sake of gaining something from it, or do you engage it for the sake of that for the sake of which the art exists? In other words, are you engaging in the art of music-making because you want something from it, or because the art is valuable for the sake of something else? In short, we can ask the question in the following way: what is the purpose Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions of achieving excellence in an art form? Answer that question in light of your own attempts to learn an art to the point of excellence. The art can be something artistic in the modern sense (music, painting) or it can be an art in the sense that Socrates and Thrasymachus are using the word. 5. We have now come to the major questions raised by the Republic, which can be summarized as follows: 1. What is justice? At this point you should at least have a sense of the question, if not yet an answer that you would prefer to promote. 2. Is it more advantageous to be just, or unjust? Who has the better life - the just man or the unjust man? In answering this question you must have some sense of what you believe the point of life to be. 1. Note the analysis - by Thrasymachus - of the just man in 349. He is defined as a simpleton and as someone who will refuse to try to gain an advantage over others. The unjust man, by contrast, is clever and smart and will know how to make his way through life. How does Socrates respond to this line of argument? Book Two 357-358 1. Summarize the three types of goods in your own words. 2. Answer this question: does the description of the three types of goods adequately summarize goodness? Or are there instead other ways to think of goodness? Resources: "Plato's Division of Goods in the Republic." Heinaman, R. (2002). Phronesis, XLVII, 4. See especially the first Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions couple of pages where Heinaman offers various interpretations of this passage. Book Two 358-362d Jean-Leon Gerome, King Candaules (1859) Queen Rodope Observed by Gyges Image Courtesy of http://www.jeanleongerome.org/King-Candaules.html 1. Glaucon here gives what has become a famous speech in favor of injustice. First of all, why is he arguing in favor of injustice? What is his stated motivation? 2. What are the major elements of the argument? How does he reason in favor of injustice, and how does this relate to the division of goods into three types? 3. What does he say that most people believe about justice in relation to the three types of goods? In which type of good does he believe most people put justice? 4. Summarize the thought experiment about the ring discovered by Gyges the shepherd. 5. Explain the ring of Gyges in relation to a choice that you have had to make or might have to make in the future. 6. Explain how the ring story might relate to the notion of a Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions social contract to which all members of society agree in order to maintain peace and establish civil society. Resources: Book Two 362e-367 Book Michael LaBossiere on the Ring of Gyges: http://aphilosopher.wordpress.com/2009/12/29/summaryof-platos-ring-of-gyges/. Philosophy.Lander.Edu: Summary of the Ring and its themes: http://philosophy.lander.edu/intro/gyges.shtml. Pay special attention to the ethical theories mentioned in the overview. Make sure that you connect the Republic from now on to those theories. They will play an important role from now on. 1. Glaucon's argument in the previous section might be summarized as an attempt to establish justice on the basis of egoistic motivations -- we are just because it's better for us than to be unjust (or at least this is what we believe). How does his brother, Adeimantus, take up the argument? What is his initial task in this section? 2. Adeimantus summarizes various sayings about justice that he believes affect the minds of the young. What impact does he believe these sayings have on young minds? 3. Interpret the passage that begins with "What about the gds?" on 365d and ends with the paragraph about Hades (about 366b). What is Adeimantus saying people believe about the relationship between justice and religion? 4. Summarize the challenge that Adeimantus and Glaucon have given to Socrates in the first ten pages of book two. 1. In general, what will be Socrates' plan of attack to respond Notes/Answers Book and Section Two 368-373 Questions 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. to the challenge that Glaucon and Adeimantus have laid down? What does he mean by "justice in small letter" and "justice in large letters"? Socrates goes on to build a city in this section. Determine, for yourself and in your own words, what is the most basic requirement of a city or of any society of individuals. On 370 Socrates enunciates a principle of specialization. Describe that principle in your own words, but also quote the relevant passage. This principle will be important to the whole of the republic, so keep it in mind as we move forward. Socrates continues to build his "city in theory." At one point the question of whether he has built "enough" of a city comes up. Respond to this question. For example, you will see Glaucon say "It seems that you make your people feast without any delicacies" on 372c. Assuming this is true, and Socrates has in fact not bothered to add "delicacies" to the city, is this a problem? Must a city - or society, if you wish - make an effort to introduce luxuries into the life of men? Or should it be structured so that it ensures that only the necessities are addressed. Speculate about the definition of "need" and "luxury." Is it possible to define these terms objectively? Don't be too quick to deny the possibility of such an objective definition. Such denials are popular, but likely wrong. Consider, for example, the silliness of claiming that caviar is a necessity. If such a claim is clearly wrong, then, there must be other "luxuries" that are also not true needs. And if there are such things then perhaps it is also true that there are some true needs and some things that can only be luxuries. 1. But don't swing too hard in the other direction, Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions either. If it is true that there are some things that simply cannot count as needs, does this mean that there are some things that must count as needs? Resources: Book Two 373-383 Summary of Republic Books 1-4 - Philosophy Pages: http://www.philosophypages.com/hy/2g.htm. Summary of Book Two - by a student of the Republic: http://cgarriott.bol.ucla.edu/plato/book2.html. See his general Republic site here: http://cgarriott.bol.ucla.edu/plato/. His "Tips" are helpful. About the good fortune my children would have, Free of disease throughout their long lives, And of all the blessings that the friendship of the g-ds would bring me. I hoped that Phoebus' (Apollo's) divine mouth would be free of falsehood, Endowed as it is with the craft of prophecy. But the very g-d who sang, the one at the feast, The one who said all this, he himself it is Who killed my son. -Thetis, recalling the death of her son Achilles 1. The city has grown, and with growth come additional needs. The first such need is the need for an army. Plato might be arguing that the city grows only because we desire luxury. The need for an army to defend the city, therefore, is directly tied to the human impulse toward luxury. Speculate about this connection and whether you think it is real. Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions 2. Note that at this point (373-374, the early stages on the argument about soldiers and armies) that Socrates is calling the soldiers "Guardians." That term will be important. Note also that at some point he will divide this group into auxiliaries and guardians, with the latter term referring to the leaders of the city and not directly to soldiers. Soldiering will be reserved for the auxiliaries, with guardians playing a loftier role as the city's political elite. 1. Note: Some author argue that this is one of those complexities that Plato believes needs to be introduced only because of the growth of the city. We require political elites, the argument goes, because we cannot have the simple life any longer once we have become large and in need of strong political leadership to keep the city from coming apart. 3. It's very unimportant in the large scheme of the Republic, but don't go the entire book without knowing what a cobbler is. 4. Is warfare a profession? Must we make soldiering a profession, or would it make more sense to have volunteer soldiers who come together only when the city is in need of an army? In the modern context, consider American society without a standing army or navy (those of you who know your Constitutional and colonial history will be especially intrigued by this question, I'm sure). 5. Socrates now launches into an inquiry into the nature of a good guardian (here to be understood as a soldier). What are the qualities that he believes make up a good guardian? 6. On 377 Socrates begins to argue that if we are to establish rules according to which our guardians will be made, then we will have to control the education of the guardian (we Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions don't make engineers without controlling their education, and we don't make soldiers without controlling their education either, Socrates might reason). To control "education" in the Athenian context, however, Socrates proposes that we must "supervise the storytellers" (377c). In what major ways does he propose to "supervise" (control) the storytellers, and who exactly does he mean by storytellers? 7. Connect the argument in these last pages of book two to modern society. Today we would call this an argument in favor of censorship. Can you see a reason to support censorship under certain circumstances? Resources: Book Three 386-390 Book Three 391-397 Griswold, Charles L., "Plato on Rhetoric and Poetry", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2012/entries/platorhetoric/. See especially Section 3. 1. Characterize the type of content that is to be excluded from the educational system in Plato's city. 2. What is the aim of education? Answer this in regard to: 1. Plato's city 2. Our own modern times 1. Explain the distinction between imitation and narrative. 2. Summarize the types of imitations that are to be allowed and prohibited. Explain the reasoning why this should be done. 3. Connect the discussion on imitation to today's youth. Does Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions the reasoning support restricting the "imitations" to which the young are exposed in today's age? Book Three 1. Name and describe the four modes of musical expression. 2. Explain how Plato argues music touches the inner part of the soul. 397-402 Consider the following exchange at 402e: Socrates: Has excess of pleasure any affinity to temperance? Glaucon: HOw can that be? Pleasure deprives a man of the use of his faculties quite as much as pain. Socrates: Or any affinity to virtue in general? Book Three 402-403 Glaucon: None whatever. Socrates: Any affinity to wantonness and intemperance? Glaucon: Yes, the greatest. Socrates: And is there any greater or keener pleasure than that of sensual love? Glaucon: No, nor a madder. Socrates: Whereas true love is a love of beauty and order - temperate and harmonious? Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Glaucon: Quite true. Socrates: Then no intemperance or madness should be allowed to approach true love? Glaucon: Certainly not. The exchange occurs in relation to the question of how lovers (people who love others) should treat their beloveds (people who are loved). The purpose of the exchange is to lay down some rules about how adult men should treat their beloved young boys. In effect, Socrates is saying that when adult men love young boys, they should refrain from having sex with them. But this implies that they can still "love" them. In response to this exchange: 1. Discuss the definition of love used by the two speakers. 2. Determine whether they are right to strictly separate love from sex. 3. Mount an argument concerning the question of whether sex is a kind of madness. Book Three 403-417 1. Summarize the training of athletes and how it contrasts with the physical training of guardians. 2. Summarize the criticisms of medicine and law that are made by Plato in this passage. 3. What is the purpose of medicine, in your opinion, after reading this passage? 4. Summarize what Plato believes can happen if one takes one type of training (music or gymnastics) too far and does not balance with the other. Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions 5. Describe the Three Tests mentioned at the end of Book Three. Note especially the distinction between guardians and auxiliaries made at about 414b. Note also the use of the "three metals" in the third test (the "Phoenician Tale"). This concept of the three metals will become important. Book Four 419-421 Book Four 421-427c 1. The book begins with a comment on the life of the guardian class. Summarize the concern voiced by Adeimantus. 2. Explain the Socratic response. 3. Do you agree with this response? 1. Desmond Lee titles this section "Final Provisions for Unity" because he sees in it Plato's last words on how to unify this large city. At this point, remember that Socrates/Plato might not be too fond of the complexity of the city that they have built thus far. As a result of this complexity, various measures must be introduced to prevent the usual causes of disunity and strife. It is diversity - opposed to social homogeneity and unity of purpose - that is being addressed here. Consider this in the context of the comments on poverty at 421e. Do you agree that both poverty and wealth are "evils"? 2. Summarize the Socratic argument that the city will be able to fend off much more rich and powerful enemies. 3. Speak broadly to the point about unity: is it impossible to achieve in a large state? Consider this in the context of the current immigration debate: can there be a U.S.-style "melting pot" and unity at the same time, or are heterogenous societies like the U.S. doomed to disunity and strife? Don't take either stance too far, however: noting that diversity leads to disunity and strife does not have to imply that such societies will not persist over time Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions (or that they will destroy themselves via civil war). On the other hand, arguing that diversity is a net positive for a nation need not paper over the difficulties involved in promoting diversity. Finally, consider just what someone might mean by valuing diversity. Why is difference inherently good, if it is good at all? This is a crucial section. Study it well. Try to get a good understanding of the role of "minding one's own business" in the argument. Book Four 427b434d Book Four 434e441a 1. State the four virtues (or "qualities," as Lee calls them) of the state. 2. Explain where each virtue is located in the people or in the state itself. 3. Finally, define each virtue briefly. Make sure to capture the definition of justice in "large letters" (that is, social justice as opposed to individual justice, which is justice in small letters). 1. Socrates builds his argument in favor of the definition of individual justice slowly. He begins the argument by drawing an analogy to social justice, defined in the last section. Just as justice in the state is a moderation and control of various conflicts that arise from disunity, it will turn out that individual justice involves the same kind of moderation and control: to be a just city requires us to control the impulses that arise in a city; to be a just individual requires us to control the impulses that arise in an individual. But this requires us to understand the conflicts inherent to human nature. To do so, we must know what elements compose the mind. Name, therefore, the three parts of the soul (or the mind, depending on your Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions translation). 2. Define each part. 3. Describe the conflicts that arise between the three parts. Focus particularly on the opposition between desire and reason. 4. Connect this opposition to the conversation about old age and sex in Book One - 329 to 330. 1. Define justice in the individual. 2. Connect the definition to the taming of the soul that is described in 442. 3. Explain the role of harmony in the definition. Book Four 441b-445 Book Five 449-457b Note that mention - at the very end of book four - of the "forms of vice" which correspond to the forms of the state. The Republic is about to take a significant detour, and we return to this topic only in book eight. A more immediate topic has to be discussed in book five: what to do with the women and children. 1. Note first Lee's comment that books 5-7 are a digression. The form of the argument in books 1-4 was roughly this: once the participants got to talking about justice, the challenge was given to Socrates to show that justice was better than injustice. In order to meet that challenge Socrates believed that he needed first to define justice. But to define justice properly one has to define it both in the state (social justice, as we would call it) and in the individual. The definition of justice in the state in turn required Socrates to explain the nature of a state (we can't define social justice without defining society, after all). So, we can break up the project as follows: 1. Establishing the question of justice and the Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions challenge to Socrates - this is done in book one and early in book two 2. Defining the state and its bounds - this is the work of books two and three 3. Defining justice in the state and in the individual this is done in book four 4. Mounting an argument in defense of the claim that it is better to be just than to be unjust - we haven't gotten to that point, and that is why Lee says that books 5-7 are a digression. We will return to the question of whether it is best to be just in book eight. So, we can say that the argument in favor of justice takes place in books 8-10. 5. What happens in books 5-7 is roughly this: Glaucon and Adeimantus want to know more about the type of state that Socrates has defined so far. They specifically want to know more about women, but they will also have questions about the training of the guardians. All of that work is taking place in these three books. 2. What question is raised by Adeimantus concerning women and children? 3. How does Socrates respond to the idea that women are not suited for certain jobs? Resources: The Rise of Women in Ancient Greece: http://www.historytoday.com/michael-scott/rise-womenancient-greece. Ecclesiazusae (Aristophanes): http://classics.mit.edu/Aristophanes/eccles.html. Lysistrata (Aristophanes): Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Book Five 457b-461 Book Five 462-466d Book Five 466d471c http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3 Atext%3A1999.01.0242. British Museum Fact Sheet on Women, Children, and Slaves in Ancient Greece: http://www.ancientgreece.co.uk/staff/resources/backgroun d/bg18/home.html. Background on the Socratic Equality Argument of Book Five: http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl201/modules/Philosophe rs/Plato/plato_on_women_plain_text.html. 1. "Then let the wives of our guardians strip, for their virtue will be their robe, and let them share in the toils of war and the defence of their country..." Locate and interpret the quotation, making sure to explain the "permission" to let the wives strip. 2. What is the "second wave"? 3. Socrates presents an analogical argument in favor of his breeding program. Explain the nature of an analogical argument. Then, explain the two analogues in the Socratic argument in this section. 1. What is the "chief aim of the legislator" in a state? 2. Socrates once again employs analogical argumentation in this section. Explain the analogy between community of property and community of men, women, and children. Relate it to Question One above and also to 419-422. 1. Socrates argues in favor of making children "spectators of war." Present an argument with at least two clear premises in favor or against this conclusion. Defend the premises with clear reasoning. Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions 2. Research the etymology and meaning of "Hellene." Book Five 471d-480 1. What is the "third wave"? 2. Socrates argues as follows at about 473c: "Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy, and political greatness and wisdom meet in one, and those commoner natures who pursue either to the exclusion of the other are compelled to stand aside, cities will never have rest from their evils - no, nor the human race, as I believe - and then only will this our State have a possibility of life and behold the light of day." Summarize the argument that he gives in favor of this conclusion. Try to list each step in the argument in a clear list of premises leading to the conclusion. 3. In the context of this argument, what is a philosopher? Give the etymological definition as used in 475. 4. Discuss the point that Socrates makes in 476 about "the lover of sights and sounds." Why is such a lover not a philosopher? 5. How does Socrates define opinion? How does he define knowledge? How do they differ? 6. Note: This is a very important point in the Republic - the argument that Socrates is putting together will play an important role in the argument in favor of justice, for it is through the love of wisdom (philosophy) that Socrates believes one becomes a true human being. You will want to make a clear note of this and return to this passage later. In addition, the definitions of opinion and knowledge will be important to the acquisition of wisdom (wisdom, after all, is a type of knowledge and is not about merely having opinions). Finally, note also the presence here of the distinction between the one and the many. While this Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions distinction is largely lost on us moderns, it was crucial to the Greeks who sought to understand the structure of reality. 1. A nice encapsulation of this section is attempted by Jowett's margin notes at 479d: "Opinion is the knowledge, not of the absolute, but of the many." In short, the lover of sights and sounds, or the lover of individual things, lacks something: he lacks knowledge of generalizations and knowledge of that which encompasses the individual. For example, I might know all about my dog, but if I never extend the knowledge of my dog into knowledge of dogs in general then I can't say something like "Dogs have hair." The most I would be able to say is "My dog has hair." This might seem strange to you, but Socrates is arguing that the person who can speak knowingly about dogs in general has knowledge, while the person who is limited to knowledge of his own dog merely has opinion. It is very important for you to ask yourself at this point why Socrates would argue like this: why does he say that I would only be holding an opinion if I could look at my dog, see that it has hair, and then claim with all of the certainty rooted in my senses that it does in fact have hair? Why is that an opinion? Hint: there is a claim being made about the relationship between knowledge and the senses. To be continued in book six, but I'll give you a little teaser: if you've ever heard about the Allegory of the Cave, then you've heard of this argument. Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Resources: Book Six 484-487a Book Six 487b497a Book Six Overview of Pre-Socratic Greek Philosophy: http://www.utm.edu/staff/jfieser/class/110/1presocratics.htm. Early Greek Philosophy, J. Burnet. Available at http://www.classicpersuasion.org/pw/burnet/index.htm. See especially the Introduction. For an overview of the problem of the one and the many, see §68 in Ch. 3 (the Heraclitus chapter, which contains a section on the one and the many). The One and the Many: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/presocratics/ and http://www.philosophypages.com/hy/2b.htm. 1. What is a philosopher? How is he or she contrasted with non-philosophers? Note: This will become relevant again at the end of book six. 2. What does Plato mean by the pleasures of the soul in this section? With what sorts of pleasures are these being contrasted? 1. What criticisms are levied against philosophers in this section? 2. What does Socrates say in response to these accusations? In particular, how does he argue that philosophical natures can deteriorate into non-philosophers? What are the possible pitfalls of the study of philosophy? 3. What draws someone away from philosophy after they have been initially inclined toward it? A pair of contrasting visions of philosophy (and philosophers) is presented in this section. What is the philosopher as Plato sees him Notes/Answers Book and Section 497a502d Book Six 502d509c Book Six 509d-511 Questions or her, and what is the philosopher as others (the masses) see him or her? Compare and contrast both visions. This section features Socrates' comments on what has come to be known as the simile of the sun. More to the point, however, it is a section that explains just why Plato believes that philosophers must become kings and kings must adopt the spirit of philosophy. In your own words, explain the section in that context. Focus on the educational content of the philosophical life: what do philosophers know, or learn, and how does this relate to the simile of the sun and the philosopher's leadership role in Plato's ideal society? Explain the Analogy of the Divided Line, focusing on the division between the parts or aspects of reality. How is it that the parts of the line relate both to an individual person's development and the nature of reality? Resources: John Uebersax on the Divided Line: http://www.johnuebersax.com/plato/plato1.htm. This passage features what is probably the most famous of all of Plato's writing: the allegory of the cave. Book Seven 514-521 You have come a long way in your reading of the Republic. At this time you should stop to take stock of what has come before. In particular, consider what you did in your reading of the divided line. Connect that to an analysis of the cave allegory and explain how the two figures come together. That is, explain how the elements of the cave story line up with the parts of the divided Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions line. Here is an image: Image by Unknown Author – Retrieved from https://opusverba.wordpress.com/tag/allegory-of-the-cave/ This section is a long exposition of Plato's theory of education of the philosopher. For our purposes what matters to our analysis are the following elements: Book Seven 521-541 1. What is the purpose of philosophical education? What is the overall effect that Plato is trying to achieve with regard to education of the philosopher? 2. What specific subjects shall philosophers be taught? Why? Explain the nature of both subjects in detail. With regard to mathematics, explain how it accomplishes (according to Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Plato) the goal that he has in mind. Explain also how it falls short of the ultimate goal of philosophy, and why it is that Plato must introduce dialectic to fulfill that ultimate project. 3. Reflect on your own mathematical training. Explain whether it has been fulfilling. Explain why it has succeeded or failed, and consider the way that you would reform it to suit what you believe would be a productive purpose. 4. Spend some time defining "dialectic" and its relationship to philosophy's mission. Consider whether this is a mission worth pursuing. In his summary of the eighth book of the Republic, the translator and Plato scholar CDC Reeve writes as follows: Book Eight 543-545 The description of the kallipolis and of the man whose character resembles it - the philosopher-king - is now complete, and Socrates returns to the argument interrupted at the beginning of Book V. he describes four individual character types and the four types of constitutions that result when people who possess them rule in a city. This passage effectively summarizes the task of book eight. In this first passage we have to contend with the underlying assumption of this approach: that it is possible to align personality types with types of states. In other words, Plato is telling us that we should be able to assess a community by looking at the types of people that live in it. He is arguing that a community of wealth-mongers, for example, will be a certain type of community, while a community of honor-lovers will be a different type of community. And, of course, the "kallipolis" will be a place filled with people who love Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions wisdom above all else. Your first question is therefore to address this assumption: is it in fact the case that when we form a community it will take on the personality of the people within it? Or, if you want to think of it in more colorful terms, think of it like this: will a society filled with nothing but selfish assholes be a certain type of society? Before you answer "Duh, obviously" think of this possible counterargument: that it might be possible for a society to improve its people. In other words, this counterargument might claim, it might be true that many of us are bad people at birth or by virtue of the training we receive from our parents. A well-formed society, however, will be one that properly channels our lower impulses and makes lemonade out of lemons - or saints out of assholes. Indeed, look no further than contemporary social theory for this kind of an argument (this might be an oversimplification, but consider it nonetheless): yes, it might be true that all human beings are selfish, but we can take that inherent drive toward selfpromotion and turn it to good account. As all individuals strive for more and more material wealth society will in fact be improved so long as there are free markets (properly regulated, perhaps) to channel that egoism in the directions most appropriate to social success. So, if people are in fact wealth-mongers that does not have to mean that the poor among us will be left out in the cold. Perhaps a rising tide lifts all boats (standard capitalist theory speaks of the invisible hand, e.g.), or maybe it's the case that where the least-advantaged among us are likely to be left behind we can make special provisions for them (i.e., we can create welfare states to prop them up). Whether you are a modern capitalist or welfarist, then, it seems Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions that you could have common ground in attacking Plato's theory that a society is nothing more than the personality of its people. Discuss. In this section Socrates explains the devolution of aristocracy (the best state, being ruled as it is by wisdom-lovers) into timocracy (sometimes translated timarchy). The best way to understand timocracy is through its root. You might know that -cracy refers to the state. This root comes from kratis, which simply means power. The root timo- comes from the Greek thumos, which means spirit. Book Eight 545-550b Recall the division of the soul into three parts: reason, desire, and spirit. A wisdom-lover (a philosopher) is someone ruled by reason. This is a rational man, one that is willing to follow reason and truth wherever they will lead. There are other types of men, however: those ruled by desire (e.g., gluttons), and those ruled by spirit. Those who are ruled by spirit are best explained in book five: these are individuals who relentlessly pursue honor and who follow their heart. They are often associated with military men because of their identification (again, in book five) with the class of auxiliaries (soldiers). So the "devolution" into a society of honor is a devolution of the soul: rather than the soul now being ruled by reason, it is ruled by the heart and promotes those goals that a military society might promote. This is not so bad as far as a devolved society goes, however. It's better than a society that is ruled wholly by desirelovers, at least, and so Plato has set it up so that the structure of book eight follows a hierarchy: as the aristocratic society dies off and philosopher-kings stop ruling our city, we lose the focus on reason and begin to be ruled by other (lesser) parts of the soul. It might not sound so bad to live in a city ruled by honorable men and women (and remember, Plato has argued for allowing women Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions to join the military - a revolutionary argument for its time). Is it? Is there a real devolution here? To answer this question you must finally come to grips with one of the central arguments of the Republic: that it is, in fact, best to be a lover of reason than it is to be ruled by any other part of the soul. Several questions follow from this line of reasoning at this point in the text: 1. Is Plato's devolutionary theory of politics correct? Without being too critical of the details (see Socrates' warning at 548d), consider whether it is possible to describe social evolution and devolution in this sort of way. Do societies go through the sorts of cycles that Socrates is describing here? 2. Has he adequately described the way that the timocratic son develops? In other words, what do you think of his armchair pscyhology here? Does it make sense that a person would turn into a timocrat in the way that he describes in these pages? Book Eight 550c555b The next stage in our social devolution tour is oligarchy, named after the oligo - which means simply a few - and therefore translating into "the rule of the few." Answer the following questions: 1. How does the oligarchy arise? 2. What are the psychological features of the oligarch? Speak in terms of the parts of the soul as Plato explains them in this context. 3. Is this in fact the way that oligarchies are? Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions 4. How does the democratic son come to be? The easy question to ask here is to ask you to examine the parallels between modern "democracy" and Platonic democracy. And, while sometimes the easy question is not pedagogically warranted, in this case it's both easy to ask, obvious that it should be asked, and necessary to answer it. Book Eight 555b563d So have at it: do you see such parallels? Mount an argument in favor of your interpretation of this passage as it relates to what we call "democracy" in the modern world. If you wish to focus on the U.S., you can do so. If not, then you're welcome to choose another nation or to speak in general terms about global democratic threads of thought or governance. So much can be said about this section that it is best to leave it to you to examine it. I do have a few notes and questions you might consider, however: Book Democracy is the second worst form of government. Only tyranny is worse. Why? Consider how democracy (the rule of the many, after the root demos for people) is driven by desire-loving people who love unnecessary desires. Is this descriptive of modern democracy, or would only a cynical jerk think like this? Who are these "drones" that he speaks of? Is the U.S. a nation of spendthrifts like the situation Plato describes here? Is the U.S. too free? 1. Is it indeed the case that "the most severe and cruel Notes/Answers Book and Section Eight 563e-569 Questions slavery" evolves from the "most extreme freedom" (564a). Or is this hyperbolic? 2. We reach here the pinnacle of the thrasymachean man, the tyrant who enslaves all and lives the life of Riley. He (or she!) is - according to Thrasymachus - the happiest of all men or women in the society. Having taken the lessons of Thrasymachus to heart, he would have risen to the top by subterfuge, trickery, injustice, and - in general - taking every possible advantage over those who are just as well as over those who are unjust. The obvious question, therefore, is this: can (or must) a tyrant be happy? Is it good to be the king? Or does the tyrant instead live the worst of all possible lives? 1. A humorous moment occurs in Book Nine, where Socrates actually calculates how much worse the life of the tyrant is than the life of the lover of wisdom: 729 times! I doubt that Plato means this literally; it's probably just a cute way of signaling to the reader that there is some kind of geometrical "worseness" or "bestness" relationship between aristocracy (the best society, led by the best men) and tyranny (the worst society, led by the worst men). 3. Must a tyranny be led by the worst person? Couldn't it be the case that a tyranny is led by a great man or woman? Maybe Plato gives too little attention to this possibility. Or is it in fact the case that a tyranny would not be a tyranny if it was led by an aristocrat or by a lover of wisdom? In other words, maybe this is Plato's way of saying that when we allow our people to be degraded into a life of pleasure (i.e., oligarchy and democracy) we are necessarily going to end up being led by some kind of megalomaniacal pleasure-loving monster who uses us for his own Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions pleasures. 1. The most obvious historical example might be Caligula, but it's possible that he was just misunderstood. 2. A recent pop culture example is the television show Tyrant, but beware: anyone who watches television for meaning and philosophy should read Theodor Adorno's How to Look at Television. 4. Describe the psychology of the tyrant in Plato's terms. What is the shape of the tyrant's soul? Book Nine 571-573 The passage cited above calls to mind several important points in the Republic: the argument concerning the tripartite nature of the soul; the argument on old age and sex from Cephalus; Plato's fetish for reason, and his understanding of human nature as finding its excellence in rationality. Here we see the clearest and most vivid contrasting element with that excellence: sexual lust. The tyrant is a man or woman who is out of control, unable to control the appetitive nature that defines human animality, and who has thus failed as a human being and not merely as a leader of men. Here we see Plato's prudishness (is that what it is?) as well as the clearest example of how he wishes to marry psychology and politics into a single field of inquiry: as we study the nature of human society so must we also study the nature of control: for if we wish to be a good society we must either be self-controlled or we must be controlled by legal means. Interestingly, this seems to mean that Plato would be comfortable with a society without laws, so long as that society consisted of the right types of individuals (rational, self-controlled, and lovers of wisdom). We might think at first that the following is the best type of life: "...someone in whom the tyrant of love dwells and in whom it directs everything next goes in for feasts, revelries, luxuries, Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions girlfriends, and all that sort of thing." - 473d, translation by GMA Grube and CDC Reeve. But of course, Plato thinks otherwise: this is the worst type of life because the "tyrant of love" is that which drives us toward our uncontrolled spiral away from a reasoned and structured life. Those of us, therefore, who become lustful creatures are literally mad, insane, devoid of rationality. All of this, of course, calls to question the very nature of desire itself: just what are the "right" desires for a human being to have? In this thread, consider these two questions: 1. How does Plato distinguish between the types of desires? 2. Do you find this tripartite division of desires convincing? Book Nine 573-580 Book Nine 581-585 What comes next - after the argument on desires and their nature is an argument about how this malformation of the soul leads into the tyrant's desire for control of society. How does Plato argue that this individual will have the worst possible life? Be specific with regard to the way that his life deteriorates after some initial (but superfluous) promise. Now that we have seen how the tyrannical life develops and devolves, we can come to some more general questions about pleasure. Plato has been keen throughout the Republic to show that the path of justice is best (remember books one and two). To do that, however, he could not simply show that the path of justice would lead to great riches (don't forget the challenge of the Ring of Gyges, not to mention common sense, which restricts Socrates from arguing that justice will have material benefits). Here we start to see that argument come to its end: Plato wants to show that justice is best, but to do this it becomes necessary to show that it leads to the most pleasurable life. This, of course, can't just mean pleasurable in the way that the tyrant's life might be Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions superficially pleasurable. Rather, it must be based on a different kind of pleasure. What is pleasure in this section? How is it defined and categorized? What types of pleasures does Plato define? Finally, explain how "true" pleasure is distinct from the absence of pain. How do the majority of the people live when it comes to their experience of pleasure? Why aren't they able to experience pleasure in the way that a philosopher can experience it? What's missing, and what can philosophy provide them? Book Nine 586-588c Book Nine 588d-592 Start to flesh out how this is leading to a final answer in favor of the claim that justice is the best kind of life. Consider, in this connection, what is perhaps the most interesting counterexample to the Platonic thesis: the life of the martyr who dies badly. Consider perhaps the death of Antipas of Perganum or the Ten Jewish Martyrs said to have been executed by the Romans. Don't focus too much on the details of any single case of martyrdom. Instead, speak to the question of whether such a bad death can be sid to be part of the best possible life. Plato is claiming that the righteous path is always best, but doesn't such a path sometimes condemn individuals to unholy terrors? And if so, how can the man or woman who suffers such an end be said to have lived the best of all lives? The end of book nine is in fact the end of the Republic's main argument. While book ten does in fact deal with many of the same themes that we have handled in the first nine books, the argumentative climax of Plato's argument occurs here. Here it is that Plato finalizes the argument in favor of the just life. Having defined justice as a kind of harmony of the soul (and of society, when we view it in large letters), he has been occupied during the last several books with developing the argument in favor of the just life. This has all been in response to the thrasymachean Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions challenge: that justice is the sucker's lot, to be followed only by those who fail to see that acting justly will lead them into a disadvantaged life that is lived for the sake and for the welfare of others. To combat this powerful line of reasoning Socrates had to redefine pleasure. It was not to be seen merely as bodily and fleshy pleasures of the moment, but had to be understood the way that a mature and rational mind would understand it: over the long term, not in the moment, and with a proper eye to "true" pleasure and not merely to pleasures that felt like pleasures because they took away our pain. If I have back pain and put on some ointment, I do not "feel pleasure," I simply feel the absence of pain. Likewise, if I have a cigarette because I think it will give me pleasure, I might be mistaking true pleasure for the absence of pain that comes with the nicotine. So I will ask the question the way that Socrates asks the question at 591: "...how can we maintain or argue, Glaucon, that injustice, licentiousness, and doing shameful things are profitable to anyone, since, even though they may acquire more money or other sort of power from them, they make him more vicious." In other words, injustice sours my soul, makes it vicious and inharmonious, and turns me into a worse person - how can this be to my advantage? Discuss. What can we say about Book Ten that hasn't already been said Book Ten about the rest of the Republic? In fact, not very much. Some (Entire theorists have seen in Book Ten a recapitulation of the rest of the Book) text. You will note, for example, that a good portion of the Book recaps the discussion in Books Two and Three concerning poetry. Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Socrates thus asks once again whether poetry shall be welcomed into our city. The result? Sure, as long as she can make a rational case for herself as a possible defender of truth. You will see if you look at the details of this argument that it all hinges on whether poetry can be rational. Can it? Feel free to discuss this in this last post. What is really wonderful and weird in this last book, however, does not have much to do (at least not on the surface) with the structured argumentation of the rest of the Republic. Indeed, it has to do with the very end of the book, Plato's account of the Myth of Er (about 614 to 621). There is no way for text to do this story justice. Unfortunately, good drawings are also hard to come by. Here is some of what Google Images has to offer: Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions All Three Images by Unknown Author –Retrieved from http://wlasseter.blogspot.com/2010/06/myth-of-er-outline.html Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions And now let's see what else we can find: Courtesy of The Monkey Dance at http://ladansedusinge.wordpress.com/2014/04/17/the-myth-of-er/. Well, how much did you expect out of Google Images? Still, it is always good to see what others' imaginations will yield when they try to encapsulate in images what they see in text. Can you imagine a true Hollywood rendition of the Myth of Er (or the Republic as a whole, for that matter)? It might not be so bad, as terribly as the production might mangle the ideas themselves. In any case, I don't want to do too much interpretation of the Myth for you. I think it's fairly straightforward and the key lies in seeing the choice at the end as the choice that you and I are making right now. The message is in fact rather trite, but here it is: we all Notes/Answers Book and Section Questions choose our lives, not just in some mythical afterlife, but in every moment and every choice that we make. And the reason to be just - if we needed one at all - is that being just makes our souls healthier. And if we need a reason to want our souls to be healthier...well then, maybe that's where reason needs to stop. Notes/Answers