Making Monsters - The Second International Symposium on Culture

advertisement

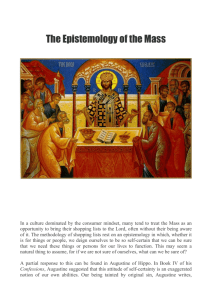

Making Monsters: the Joy of Creation, the Fear of Death and the Ethics of Interaction Design Ann Light Curiosity, inventiveness and the desire for novelty… all these qualities come into the reckoning when we consider interaction design. We observe with delight the resourcefulness that users apply to making standard tools work better for them. And this everyday appropriation is only a pale shadow of the ingenuity of the designers who conceived the devices, or the industrious scientists and engineers who furnished the technologies on which they are based. Some of that ingenuity is applied to making life happier, profounder, kinder, sexier and more fun. But similar technologies are also applied to controlling environments, managing people, increasing productivity and enhancing safety and security. Our vulnerabilities as tender and perishable animals have inspired a set of applications which seek to turn the environment into a person-sized protective layer, ready for storms, fires, wild beasts and other humans competing for finite resources. Thus, interactive computing systems are the latest in a long line of tools designed as part of two very human impulses. In this document, I discuss each through the writing of a commentator on the relation between culture and technology. I draw on Stiegler’s technics (1998) and Virilio’s military-industrial complex (2000) and examine how these social critics address the nature of humanity through our making of technology, as a prelude to discussing our responsibility as makers and researchers. The first of my commentators is Bernard Stiegler, who takes on Heidegger’s analysis of the relation between people and technology and argues that it is impossible to separate “organised inorganic matter” (namely technics) from the evolutionary development of the human being. He positions technics as primordial, since it was/is a process of externalisation - or the ‘pursuit of life by means other than life’ - that allows us to capture and share our existence. Technics, for Stiegler, makes temporality possible and with it our historical experience of time, memory, and consciousness. It is what allows the shared inheritance of past possibilities – through language, technique, and culture – that we reactivate through future projection to individuate ourselves in relation to our shared community. In other words, we need no justification for the act of inventing – it’s what we do as humans and to be human. Externalisation is as old as we are and we can only know ourselves through it, both in the sense that it provides the lens and in the sense that, for us, there was no before the imagining, creating and recording. What we are doing with ICT is extending the reach of our desire to preserve and share. The other commentator is Paul Virilio, who sees speed as the primary force shaping civilization and the pursuit of it as part of a permanent assault on the world and on human nature. This produces a macabre interpretation of technologies of communication with their world-shrinking capacities. For Virilio, information and communication tools are weapons that extend beyond the body and allow for disinformation and propaganda wars as a supplement to the contact wars that have always been waged. His criticisms of automation in general are closely connected to the development of his concept of endo-colonization — what takes place when a political power like the state turns against its own people, or, as in the case of militarized techno-science, the human body. In this reading of technology, we are in thrall to our fears, giving power to the apparatus that magnifies and distorts our anxieties about safety, adequate resources and survival into crushing socio-technical processes which finally threaten our wellbeing in a variety of different ways. This dark vision, which regards invention as the product of a will to overcome and control, is in contrast to the inventiveness of Stiegler’s humanity, but compatible with it since we are embodied creatures that must always exist in the context of our own mortality. Making is intrinsic, but what we make is not only informed by a desire to pass culture forward, but also by our angst as fragile ephemeral beings. Making accounts for buildings and structured settlements but also the ravaging of other species and the destruction of habitats, including our own. Left to run rampant, anxiety produces a world that addresses human vulnerabilities but simultaneously exploits them for the perpetuation of the state and - more recently - the depoliticizing neoliberalism of the free market. In other words, a principal reason we invent is to protect ourselves from our harsh and ultimately fatal environment and, in so doing, damage both ourselves and that environment. In which case, we need every justification for what we invent and how it is used. Indeed, the stories we tell ourselves about technology - the fiction and the newspaper reports that pervade our culture - speak of monsters. Sometimes it is the inventor, sometimes the invention that is un-human and/or anti-human in its ambitions or actions. The monsters we describe to scare ourselves threaten life and are seemingly unstoppable. These tales might be regarded as stories of conscience; as parables: a collective telling of the significance of regarding technics as an interaction embedded in life and part of a highly developed ecology of people, artefacts and processes. Behaviour that does not acknowledge this context is portrayed as psychopathic. It is interesting to reflect on the film The Corporation (2003) and related book The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power (Bakan 2004), which narrates the growth of the company as psychopath, ruthless in pursuit of a single interest, unconcerned with social norms and others’ needs, free of empathy and ready to appropriate anything for a quick profit. Noam Chomsky is interviewed in the film: “Corporations were given the rights of immortal persons [in the USA]… but then special kinds of persons, persons who had no moral conscience… a special kind of persons which are designed by law to be concerned only for their stockholders …and not, say, what are sometimes called their stakeholders, like the community or the work force or whatever.” These corporations drive the pursuit of technology in Virilio’s vision, in partnership or tension with the state, harnessing our gleefulness and fear and behaving as the seemingly unstoppable monster. It is not the robot or computer, but what automation, computerisation and networking have enabled our psychopaths to carry out in terms of organisation and spread that calls for heroes... In contrast to the giant transnational commercial structures of late capitalism, individual humans (and therefore designers and design researchers, social scientists and all those who observe and steer the shaping of technology) have a moral nature. Implicit in the theory of technics as primordial is recognition of a human power to reason and attribute cause and effect. With such attribution comes a sense of responsibility. And as Voltaire (1734) rejoindered in a discussion about the selfishness of self-interest, it is through (the recognition of) our mutual needs that we are useful to the human race. But there is increasing evidence that we are not just motivated by a rational and thus enlightened self-interest. Recent neuroscientific research suggests that disgust at selfishness and desire for fairness are as hard-wired as making activities, overriding logical analysis (see Tabibnia et al 2008). So, while we might not wish to curtail our unbridled creativity or admit our fear, we share a potentially conflicting feeling that selfishness is unacceptable and that mindfulness and ecological sensitivity (see, for example, Blevis 2007, Buckmaster Fuller 1969, Papenak 1985, Sengers et al 2005, Suchman 1987) must also be part of any design process. And while this emotion may not feature strongly in the practices of technological innovators or the minds of the despots that use technologies to control others, it is alive in the HCI researchers working in response to untrammelled inventiveness by finding application for it. This last impulse, for fairness, is of a different order than many of the design considerations that we consider important, such as wellbeing, sensuousness, affect, connection and intimacy, since it supports the social conditions in which these can be meaningful. It requires us to reflect on our embodiment and our situatedness, informing the design choices we make as creatures embedded in our world through our technologies. We can only prevent the construction of monsters with hindsight, but applying more foresight is within our grasp and we can design tools that help us (Light 2011). There are, it is clear, major questions to be asked about what we design. There are also more subtle nuances to this argument about the role of researchers. Social science/design researchers are perfectly placed to observe the invention and exploitation processes of new technology creation and contribute to the development of new, more considered, practices through reflective and critical activities. We might ask how far ethics is our business. How far is intervention, through data collection, commentary, or more deliberate action research, itself an ethical business? And we might argue that the act of interpretation that underpins all social science and design research, when we make sense and attach salience and value to a phenomenon, is the basis of ethics and inseparable from it. For many years we have been asked to make interaction better at the level of the individual machine or network. Here is an argument to apply broader social knowledge in the service of relations between people, artefacts and processes. This is a different kind of interaction design and one which acknowledges that, given our antecedence, ethics is inseparable from observation. References Blevis, E. (2007) Sustainable Interaction Design: Invention & Disposal, Renewal & Reuse. CHI’07 Buckmaster Fuller, R. (1969) Operating manual for spaceship earth, Southern Illinois University Press, IL Light, A. (2011) Digital Interdependence and How We Design for it, Interactions, Mar/Apr 2011 Papanek, V.J. (1985) Design for the real world: human ecology and social change (2nd edn), Academy, Chicago Sengers, P., Boehner, K., David, S. and Kaye, J. (2005) Reflective design. Proc. CC '05, ACM Press, 4958. Stiegler, B. (1998) Technics and Time, 1: The Fault of Epimetheus, Stanford: Stanford University Press. Suchman, L. (1987) Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tabibnia, G., Satpute, A. B., & Lieberman, M. D. (2008) The sunny side of fairness: Preference for fairness activates reward circuitry (and disregarding unfairness activates self-control circuitry). Psychological Science, 19, 339-347 Virilio, P. (2000) The Strategy of Deception, London: Verso Books. Voltaire, F-M. A. (1734) Lettres philosophiques (Philosophical Letters)