File

advertisement

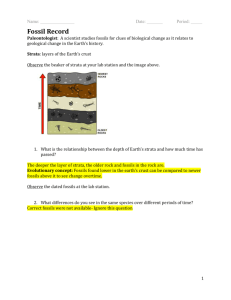

EVIDENCE FOR EVOLUTION There is a wide range of evidence for evolution from both palaeontology and from living organisms. The following is a brief summary of some of this evidence: (1) Fossil evidence The fossil record, although certainly not complete, does indicate several major evolutionary themes over long periods of time. The trend from simple to complex organisms and the trend from aquatic to terrestrial organisms is clearly evident from the fossils, as is the development of sexually reproducing organisms from asexually reproducing ones. (2) Transitional forms Transitional forms (or link organisms) are evident in the fossil record as well as amongst living organisms. Fossil remains of a fish (Crossopterygian) that could absorb oxygen directly from the air have been found in rocks formed 400 million years ago. This fish, in addition to the usual scales, fins and gills also had bones inside of lobe-fins which suggest it could drag itself over land. It also had lungs and it is thought that amphibians developed from fish along this line of descent. The extinct Archaeopteryx is most likely a link between the reptiles and birds. An example of a living transitional form would be the Peripatus which is a link between the annelids and the arthropods. (3) Evidence from taxonomy The characteristics of organisms differ in such an orderly pattern that they can be fitted into a hierarchical scheme of categories. Our present, well-established classification scheme, first developed by Carolus Linnaeus, shows relationships between groups of organisms that follows evolutionary development. If plants and animals were not related in evolution but had been independently created, their characteristics would most likely be distributed in a confused, random fashion and a well-organised classification scheme would be impossible. (4) Morphology There is much evidence for evolution from comparative anatomy. The existence of homologous structures is particularly striking in vertebrates. All vertebrates show some form of a basic five-digit plan in the bones of their limbs (the pentadactyl limb). It would be difficult to explain why the limbs of such diverse creatures as a human, a whale, a bat and a frog all shared a common basis for the construction of their limbs if there were no evolutionary relationship between them. As well, the presence of vestigial organs which are useless or degenerate structures found in the modern organism points to the existence of some ancestral forms in which these organs were once functional. The human tail bone at the base of the spine is such a vestigial structure. (5) Comparative embryology: “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” First described by Ernst Haeckel in 1866, this principle suggests that embryos, in the course of their development, recapitulate or repeat the evolutionary history of their ancestors. The early human embryo resembles a fish embryo in that it has gill slits, pairs of aortic arches, a fish-like heart with a single atrium and ventricle, a primitive fish-like kidney and a tail that can wag. Later in its development, the human embryo resembles a reptile with closed gill slits, fused vertebra, a new kidney and an atrium partitioned into left and right chambers. Still later the human embryo develops the four-chambered heart of birds and resembles a chick embryo more than an adult human. Even after seven months of development the human embryo (if covered with hair) looks more like a baby ape than a human being. (6) Biochemical evidence Chemical similarities at the cellular level, such as amino acid sequences in common plasma proteins and tissue enzymes, can be used to confirm the evolutionary relationships within groups of organisms. Cytochrome c, a respiratory chain enzyme, has been studied extensively in this regard and many species have been compared. The further apart any two species are evolutionarily, the greater the number of differences in their amino acid sequences. The universality of genetic information (i.e. human DNA can function perfectly in bacterial cells) is strong evidence for a common ancestor for all living things. (7) Geographic distribution Particular types of plants and animals are found in certain continents and not others. For example, the animals and plants of Asia and Australia are very different. This phenomenon was first described by Alfred Russel Wallace who suggested Wallace’s Line to demarcate the distribution of these organisms. It is widely accepted that Australia’s unique mammals and flowering plants resulted from periods of evolution in isolation.