Att to 184 Rossiter

advertisement

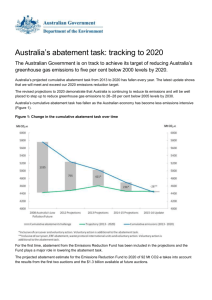

SUBMISSION ON POST-2020 EMISSIONS REDUCTION TARGETS BY: David Rossiter, MEngSci, BSc, CPEng (Ret), FICE, FIEAust Former Renewal Energy Regulator, and former Greenhouse Energy and Data Officer Page 1|7 Introduction and Background Most of the 196 countries in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), representing well over 80% of the global total of emissions, have agreed that the effects of climate change need to be limited to a maximum temperature rise of 2 degrees Celsius. Pledges were made following the Copenhagen Conference of Parties in December 2009. The Australian Government is part of that international commitment known as the Copenhagen Accord. Article 1 of the Copenhagen Accord states: We underline that climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time. We emphasise our strong political will to urgently combat climate change in accordance with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. To achieve the ultimate objective of the Convention to stabilize greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system, we shall, recognizing the scientific view that the increase in global temperature should be below 2 degrees Celsius, on the basis of equity and in the context of sustainable development, enhance our long-term cooperative action to combat climate change. We recognize the critical impacts of climate change and the potential impacts of response measures on countries particularly vulnerable to its adverse effects and stress the need to establish a comprehensive adaptation programme including international support. As the issues paper states, global warming is a fact and Australia has already experienced 0.9 degrees C of warming, mostly since 1950. The scientific basis of global warming is well established and has been known for over 100 years, yet carbon dioxide equivalent levels are still increasing rapidly into the atmosphere. To limit global warming to no more than 2 degrees C, total emissions to the atmosphere must be significantly and rapidly reduced. Carbon dioxide equivalent levels in the atmosphere have already risen to over 400 parts per million (ppm) which is around 42% above the highest levels in the 800,000 year period prior to industrialisation (pre-1750). This is why Australia already has experienced 0.9 degrees C warming and why further warming is already locked in to the system. For the world to have any chance of remaining below the agreed 2 degree limit, it has been calculated that total global emissions to the atmosphere should be effectively zero by 2050. This amount of total global emissions has been described as a carbon budget. The world carbon budget is estimated to be 565 billion tonnes, based on studies done using over forty different climate change models. Ensuring that the production of greenhouse gases does not exceed that amount over the next 35 years is the challenge facing the entire global community. Australia’s share of that world carbon budget is only around 8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions. The current target of 5% reduction in emissions (from 2000 level) by 2020 represents emissions of around 531 million tonnes (Mt) per year. If this rate continues unchanged, Australia’s total carbon emissions budget will all be exhausted in about fifteen years, giving society and industry only a short time to adapt to a net zero emission world. Page 2|7 So, Australia’s challenge is to steadily reduce our emissions over a longer period, so that our 8 billion tonne budget is gradually used up over the next 35 years, instead of the next 15 years, slowly reducing emissions by under 3% per year. This would have the benefit of allowing a graduated transition to a net zero carbon economy over that period. What should Australia’s post-2020 target be and how should it be expressed? The post-2020 target should be expressed in the context of the Copenhagen Accord, meaning that countries have agreed that they will be producing virtually zero net emissions by the year 2050. So, we know what the end result and the time frame are. Zero percent by 2050. While that is unambiguous, there is clearly a need to set interim targets, so that we can measure how we are tracking and whether our policies and strategies for getting there need adjustment. At the very least, interim decadal targets for 2020, 2030 and 2040 should be established. To repeat, we have only 35 years to reach our zero emission commitment. I propose the following emissions reduction targets, utilising the year 2000 as the base: 2020 – 19% 2030 – 40% 2040 – 70% 2050 – 100% The current target for 2020, which seems likely to be met, is 5%. The Government committed to increasing that target as high as 25% if there was evidence of similar commitments from key international players. It is now becoming apparent that there is real movement on the international front, especially in the lead-up to the international climate change meeting in Paris later this year. Countries have been asked to declare their commitments by June, and all the indications are that the key players, including China, the US, Brazil and the EU, are making the sort of commitments that should demand a complementary significant commitment from Australia. In addition, on 20 April 2015, evidence was published to show a number of these countries have used the current UN process to ask Australia a number of questions about its commitment to reducing emissions. For instance, China accused Australia of doing less to cut emissions than it is demanding of other developed countries, and asked it to explain why this was fair, and the US asked whether the emissions reduction fund was the main replacement for carbon pricing, or whether Australia planned to introduce other policies. In addition, the European Union questioned whether the emissions reduction fund could deliver a 15 or 25 per cent cut by 2020 – targets Australia has said it would embrace if other countries did the equivalent. Page 3|7 The Australian Climate Change Authority has already expressed the view that Australia could raise its 2020 target and meet a target of 19% without too much difficulty, especially as it has excess credits from the Kyoto period targets of about 4%. I support that position, and would note that an increased target for 2020 would make it easier to achieve the post-2020 targets. From the Government’s rhetoric, it looks as if the emissions for 2020 should be close to 5% below 2000 levels or even lower, showing that Australia can change from growing emissions to reducing emissions, described as turning the ship around by some, and decoupling GDP growth from growing emissions. This is a good news story for Australia’s international negotiating position. As for a base year for emissions reductions, sticking with 2000 is easier to explain than using earlier dates (1990) or complicating it by using half decades such as 2005 as base years. Proceeding with an inadequate post-2020 target or delaying the target implementation would have the following implications: 1. Australia will be placed under intensive international pressure, possibly including sanctions, and will lose any right to be regarded as an international player of substance. 2. Much tougher decisions will have to be made down the track as we will have exhausted too much of our 8 billion tonne allocation, with resultant increase in social, economic and environmental impacts. 3. Instead of spreading the costs of transition to a net zero carbon economy over 35 years, the costs will be experienced more in the period 2030-2050, causing an unfair amount of economic pain to the next generation. 4. The current business world will receive very mixed messages on the value of investment in Australia, its potential for increased sovereign risk and on the potential for stranded assets. 5. It is already clear that there will be no more coal-fired power stations built in Australia due to the likelihood of stranded assets, and almost all those already in existence are reaching the end of their design lives. This has significant implications for the country’s power generation capability. 6. We will be missing the opportunity to be a key player in the low carbon technology industries, including renewable energy and electric vehicles. What would the impact of that target be on Australia? A post-2020 target of 40% by 2030 is definitely achievable, particularly if the Renewable Energy Target is also increased to 40% by 2030. This policy, which was introduced by the Howard Government, has done much of the heavy lifting so far in helping Australia to meet its current targets. The recent Warburton review of the RET showed that the costs were less than predicted and currently the benefits exceed the costs – a win for the economy, society and the environment. The two biggest contributors to Australia’s carbon emissions are coal and gas-fired electricity generation, and the burning of fossil fuels in the transport sector. The development and uptake of new technologies such as renewable energy, electric and hybrid vehicles, are already contributing Page 4|7 to reduced emissions in these sectors, and, with policy encouragement, it is quite feasible that a greater shift to low carbon alternatives in these sectors alone can largely deliver the interim targets. We already know that almost all the coal-fired power stations in Australia are reaching the end of their design lives. They have long since amortised their costs (hence the need for the RET to enable renewables to compete), and there is virtually no likelihood that new coal-fired power stations will be built to replace them. The communities which live around these power stations are aware that the associated employment is time limited and will also welcome the demise of the disease-causing pollution associated with the industry. However, Governments will need to encourage new sources of employment in these regions if significant social impacts are to be avoided. In addition it can be reasonably be expected that, in the next 35 years, further new technologies and advances in existing technologies will give yet more valid options towards the achievement of these targets. Bear in mind technology is advancing at an ever increasing rate – one need only look back 35 years to see what advances have occurred in the period from 1980 to 2015 to conjecture what might happen in the future. We have had the expansion of the internet, mobile phones, radical improvements in motor vehicle fuel consumption, the ability to self-generate electricity from our roof tops, combined cycle power generation, super critical power plants, plus many more beneficial changes in the last 35 years. All have arrived at what appeared to be premium costs initially but have been quickly adopted and assimilated as costs have fallen rapidly with increased deployment. The impact of these targets on Australia can be estimated quite precisely using existing costs and current technology. But it is also well known (see Grattan Institute reports on the topic) that because the costs of existing and new technologies will fall with increasing demand, and more new technologies and smarter ways of doing things can emerge through properly structured markets, any costs derived at this point should be regarded as the upper bounds for costs. Ultimately, costs will be lesser. For example, it was estimated when the Renewable Energy Target (RET) was first mooted and costed (around 2000, less than fifteen years ago) that the price of Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) would exceed $40 per MWh by 2005 (for an annual supply of 3.4 million RECs) and that most of the renewable energy would come from burning sugar cane waste (bagasse) because that was the cheapest technology at the time. More than ten years on, RECs still cost less than $40/MWh (for an annual supply of 18 million) and come mostly from solar photovoltaics and wind generation, with some bagasse, as these are now cheaper technologies – in the case of solar PV the capital costs are about one sixth of those experienced in 2000. So what economic impact might there be as we seek to reduce emissions from the proposed 19% target in 2020 to 40% by 2030? History tells us that if a market can be set up properly the costs are likely to be lesser than those initially calculated which tend to be upper limits of cost because they do not include sufficient allowance for the reduction in costs achieved through competition, decreased costs due to increased demand for a given technology and innovation coming from other actors in the market. Page 5|7 With the right policy environment these targets can be implemented with very little effect on the economy with beneficial effects on jobs, business and the environment. And, it seems likely that, with more incentivised participants in a polluter pays market based scheme more options will emerge and costs will tend to fall per unit of abatement. About 75 Mt per year emissions reduction would be required to meet the 40% target in 2030 (with lesser amounts in the years leading up to 2030 from 2020) which at, say, $10 per tonne would cost about $750 million per year or under 0.05% of GDP if there were no co-benefits from the emission reduction activity. Experience shows us that co-benefits will reduce the costs still further and may even completely negate them. For instance, it should be borne in mind that the recent Warburton RET review showed that cobenefits of emission abatement under that scheme now exceed the costs. In other words, the abatement costs were not only less than $10 per tonne but effectively less than zero. In that context, the estimated 0.05% of GDP cost should be regarded as a worst case scenario. (To get some feel of what a GDP cost of 0.05% in 2030 would mean, if GDP were rising at 2.5% per year in 2030 this would mean the level of GDP reached on 1 Jan 2030 without such a scheme, then that same level of GDP would be reached a week later on 8 Jan 2030.) Interestingly, the Warburton RET review also showed a 30% target for renewables by 2030 was cheaper for consumers than options reducing the 20% target for 2020 as about $2 billion per year were wiped off peak electricity costs on hot days by renewables. Which further policies complementary to the Australian Government’s direct action approach should be considered to achieve Australia’s post-2020 target and why? There will need to be a range of supplementary policies, including market-based mechanisms, as the direct action policy will be insufficient, by itself, to deliver any target over and above the existing 5% by 2020 target. The Abbott Government made it abundantly clear when it introduced the direct action policy that it did not plan to pay polluters for their abatement after 2020, and the $2.55 billion so far allocated for the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) would be unlikely to extend beyond a 5% target. Since the emergence of the carbon budget approach, it is now evident that much larger targets will be required both up to 2020 and beyond. It is also obvious that expansion of the direct action (ERF) approach is not the answer, as it would be prohibitively expensive and unsustainable in the current fiscal environment. During the development of the ERF policy, cost abatement curves were produced for potential emission reduction options and it was estimated that the maximum cost of abatement the Government would need to pay polluters would be about $8 per tonne of carbon dioxide. Page 6|7 With an emission reduction direct action policy in place, a complementary polluter pays policy could be introduced to speed up the direct action process, enhance implementation rates and provide a boost to innovation. In the UK in the early 2000’s a similar situation arose as the Non Fossil Fuel Obligation (NFFO), a government subsidised renewables payment scheme rather like direct action, was sped up by introducing a market based polluter pays system. Both schemes – direct action and polluter pays – worked successfully in parallel for some years, boosting emissions reduction substantially. If abatement for the ERF can be done at around $8 per tonne, then a market based polluter pays system is likely to cost less for each tonne of abatement as it has more incentivised participants looking for legitimate abatement innovations rather than an options limited polluter paid system like the ERF. Some of the abatement innovations we are likely to see will include improving energy efficiency of energy production, more efficient use of energy transmission and distribution, more efficient use of energy produced, switching to low carbon fuels, adoption of more renewables, establishment of sequestration projects, and, adopting new and cheaper technologies such as better battery technology for electric vehicles and household power systems, as they become more widely available over the interim 15 years. Page 7|7