The Evolution of Painting

advertisement

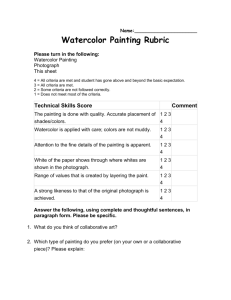

Panicali 1 Darren Panicali Professor Jablonka MHC 100 23 November 2010 The Evolution of Painting Through Time When we gaze at paintings, some unique, enigmatic feeling within us is fiercely triggered and strongly evoked. It is something innate, something indescribable. Some will label it as beautiful, and some will depict it as a spiritual experience. As William Segal put it, you “forget everything except what is here right in front of you” and “there is something here that goes beyond applying paint on a canvas.” Whatever it may be, it has been with us since the birth of the human mind so long ago. Since even before the dawn of civilization, primitive men would smear raw materials onto crude surfaces for just the same essential reason we apply refined paints to professional canvases today: there is something liberating and intriguing in selfexpression. But despite the same general feeling experienced among disparate works, the subjects portrayed, media used, techniques employed, and other aspects of a specific painting can convey particular messages and elicit intricate feelings unique to that work. Needless to say, paintings found today differ significantly from those discovered on cavern walls. They have evolved through the ages from prehistoric times to the contemporary era with alarming vigor, and with a focus on four different paintings, we can come to comprehend how paintings have changed as well as the messages and feelings behind them. Below are paintings from chronological eras respectively representing in sequence the origin of man, the dawn of civilization, the establishment of sophisticated techniques, and the birth of explosive creativity and expression. Panicali 2 Painting 1 Painting 2 Painting 3 Painting 4 Before cities developed and record keeping began, hunter-gatherer communities dominated Earth, and they left their mark with cave paintings. The first painting (Painting 1) above displays 30,000 B.C. horse heads from the Chauvet Cave, which houses some of the earliest paintings ever uncovered. With the onset of civilization, more elaborate paintings surfaced, as with the second painting (Painting 2), Nany's Funerary Papyrus, illustrating an Egyptian woman being judged on her way to the afterlife in 1040 B.C. The third painting (Painting 3) shows Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam, painted upon the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in 1511. This represents the age of refinement of painting to include depth, realism, and higher elegance. And the final painting (Painting 4) from 1952, Willem de Kooning’s Woman, I, demonstrates the abstract expressionist, cubist era of rebirth of the same creativity that inspired that first cave painting by man so long ago – the journey into something new and original. The motivation and particular messages of paintings have, with time, deepened in their scope and their demonstrated awareness of the world. The impetus for prehistoric painters to make the first paintings is hotly debated, but the creator of Painting 1 most likely wanted to honor the creatures with which he or she shared a strong bond. The artist might have desired to preserve the memory of the horses that served him or her so well or represent the beauty of the creatures themselves. As civilization sprouted, spiritual themes began to show up in art, depicting burials and posthumous existence. Painting 2’s portrayal of a woman’s traversal to the afterlife was probably crafted to commemorate her success and venerate her memory. Jump a Panicali 3 few thousand years to the Renaissance, a period when trade flourished and painting gained greater social and religious value and typically signified great wealth. Painting 3’s depiction of Adam and God displays clear religious rationale and significance, and it glorifies the human body in its natural state; only the Church or the wealthy could have had such things painted at the time. As time passed, creative ideas expanded and artists deserted “the habit of looking at every object or body as though it were complete in itself, its completeness making it separate” and began to convert structures “to arrangements […] so that the elements of any one form were interchangeable with another” (Berger 86), as with Painting 4 at a mid-1900s high point in the abstract expressionist, cubist movement. Its abstract woman was painted probably to distort the classic female image and force us to re-evaluate her in different lights, aided by surrounding diverse colors and shapes. But where would these paintings be without their components? The medium, materials, and techniques of a painting display a trend of cultivation and advancement as time has proceeded. Painting 1 was scrawled onto a cave wall, one of the only surfaces available for art to last against the elements indefinitely, and it was probably made with a mixture of scavenged nearby organic material and minerals. The medium was crude, as were the paint elements, which were simply applied in rough, rudimentary strokes. As prehistoric man evolved into “civilized” man, better media like paper were developed, and Painting 2’s papyrus medium is indicative of this, painted on with greater accuracy and in a profile mode. The paint must have been more intricate in its constituents, but it was still limited to local materials and rarely might have incorporated resources obtained through trade caravans. As the separate nations of the world became more interconnected in Painting 3’s time, more materials were available for more elaborate paint composition – various textures and new colors – and fresh media were developed, like the precursors to today’s canvases. But Painting 3 was done on a Panicali 4 building ceiling, depicting how painting was transcending portable media, becoming more of an active, permanent part of people’s lives – “from the realm of ideas to the realm of experience,” shared a Metropolitan Museum of Art speaker. It exhibits realism in the human image and depth using shadow. Painting 4 represents the shift of painting to every media imaginable, all being painted with an exorbitantly extensive array of paints made available because its era was postIndustrial Revolution and international trade was well-established. Techniques expanded radically by this time, including random strokes and blotches, application of many more colors, heavy use of contorted lines and shapes, creation of three-dimensional paintings, and other revolutionary tactics that characterize the abstract and cubist modes. But fully understanding this progression is impossible without also considering the painter and the painted. The subject and artist of a painting provide incredible insight into its inner workings, and they tend to become more complex with the passage of time. Painting 1 depicts animals, showing respect for nature and the animal kingdom, and the artist was a primitive cave dweller in a time when no paintings previously existed, hinting at his inherent need to create this image. Painting 2 shows a ritual singer who was the daughter of a high priest, her heart being successfully judged on a scale to pass into the afterlife (“Nany’s Funerary Papyrus,” par. 1), placing emphasis on the Egyptian value of life after death. It could be that a lower or middle class artist painted this for the ruling class, suggesting a class distinction in art where the rulers profit from the labors of the masses. Painting 3 was constructed by Michelangelo, a master artist of the Renaissance, denoting that it would be a highly celebrated and detailed piece. Its subjects, Adam and God, suggest that men saw God in their own image and that there was a subtle yet cogent connection between man and the Almighty. The subject of Painting 4 can be said to be a woman, but gallery speaker Deborah Goldberg stressed that there was movement away from subjects and concentration on Panicali 5 different perspectives and methods in abstract expressionism; the woman’s distortion agrees with this. Its artist, like many now-famous artists of the era, had worked his way up to fame and was not one of a few masters as painters of the Renaissance appeared. They were simply common people whose work was noticed and celebrated, and word of mouth spread and they accumulated fame. This was an important shift in painting, its practice being opened up to the masses and anyone being able to rise in eminence based on the skill and pleasantness of their work. These four paintings involved similar motivations, media, materials, techniques, and subjects, with each work building upon those of the previous work, and so the further in time you go, the more divergent the paintings become from the earlier ones because the practice of painting is revolutionized from era to era. If we imagine Painting 1 as an innermost circle and the other three as outer circles encompassing each other sequentially, we see that each similarly holds aspects used in the previous one and simply builds upon the foundation. For instance, people today, like cave dwellers, still paint on crude surfaces. But just like you wouldn’t find a caveman with a beret painting on a canvas with a fine brush, this image also implies aspects unique to each painting, and we saw this with progressive differentiation in motivation and subjects (to honor/depict animals vs. spiritual scenes with people and/or deities vs. human versatility/creativity) and in media, materials, and techniques (cave wall, crude paints, and primitive strokes vs. papyrus, superior paints, and complex application vs. chapel ceiling, intricate paints, and sophisticated technique vs. professional canvas, endless/best paints, and abstract/cubist mode). But one thing has remained constant as the ultimate similarity since the birth of painting: the ability to inspire. So despite all this “evolution,” whether you are a caveman or an 21st century intellectual, paintings will always reach deep into your core and stir your imagination and emotions – perhaps the greatest instance of painting evolution of all. Panicali 6 Works Cited Berger, John, and Geoff Dyer. John Berger: Selected Essays. London: Bloomsbury, 2001. Print. De Coning, Willem. Woman, I. 1952. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Museum of Modern Art: The Collection. 2010. Web. 20 Nov. 2010. Horse Heads. 30,000 B.C. Chauvet Cave. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. 2000-2010. Web. 20 Nov. 2010. Michelangelo. The Creation of Adam. 1511. Sistine Chapel. Public Domain Photos and Images. 13 June 2010. Web. 20 Nov. 2010. Nany's Funerary Papyrus. 1040 B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Works of Art. 2000-2010. Web. 20 Nov. 2010. "Nany's Funerary Papyrus | Highlights | Egyptian Art | Collection Database | Works of Art | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York." The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Metmuseum.org. 2000-2010. Web. 22 Nov. 2010.