Reflections on Lake Baikal By the time we arrived at Olkhon island

advertisement

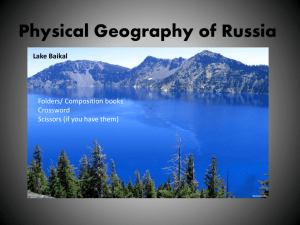

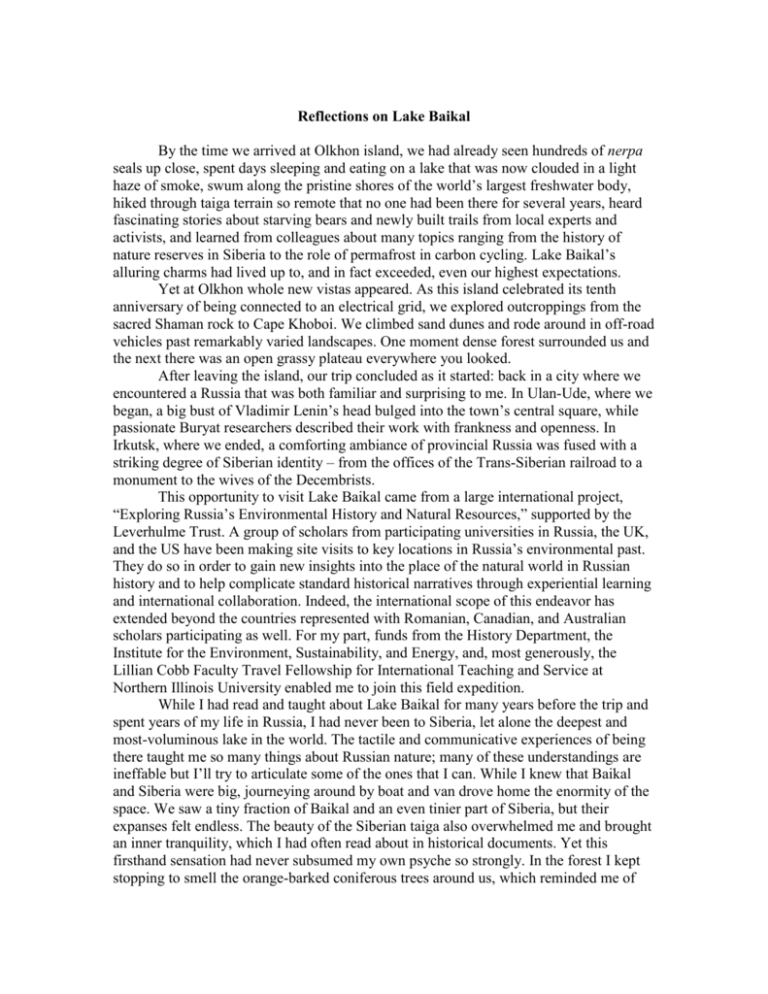

Reflections on Lake Baikal By the time we arrived at Olkhon island, we had already seen hundreds of nerpa seals up close, spent days sleeping and eating on a lake that was now clouded in a light haze of smoke, swum along the pristine shores of the world’s largest freshwater body, hiked through taiga terrain so remote that no one had been there for several years, heard fascinating stories about starving bears and newly built trails from local experts and activists, and learned from colleagues about many topics ranging from the history of nature reserves in Siberia to the role of permafrost in carbon cycling. Lake Baikal’s alluring charms had lived up to, and in fact exceeded, even our highest expectations. Yet at Olkhon whole new vistas appeared. As this island celebrated its tenth anniversary of being connected to an electrical grid, we explored outcroppings from the sacred Shaman rock to Cape Khoboi. We climbed sand dunes and rode around in off-road vehicles past remarkably varied landscapes. One moment dense forest surrounded us and the next there was an open grassy plateau everywhere you looked. After leaving the island, our trip concluded as it started: back in a city where we encountered a Russia that was both familiar and surprising to me. In Ulan-Ude, where we began, a big bust of Vladimir Lenin’s head bulged into the town’s central square, while passionate Buryat researchers described their work with frankness and openness. In Irkutsk, where we ended, a comforting ambiance of provincial Russia was fused with a striking degree of Siberian identity – from the offices of the Trans-Siberian railroad to a monument to the wives of the Decembrists. This opportunity to visit Lake Baikal came from a large international project, “Exploring Russia’s Environmental History and Natural Resources,” supported by the Leverhulme Trust. A group of scholars from participating universities in Russia, the UK, and the US have been making site visits to key locations in Russia’s environmental past. They do so in order to gain new insights into the place of the natural world in Russian history and to help complicate standard historical narratives through experiential learning and international collaboration. Indeed, the international scope of this endeavor has extended beyond the countries represented with Romanian, Canadian, and Australian scholars participating as well. For my part, funds from the History Department, the Institute for the Environment, Sustainability, and Energy, and, most generously, the Lillian Cobb Faculty Travel Fellowship for International Teaching and Service at Northern Illinois University enabled me to join this field expedition. While I had read and taught about Lake Baikal for many years before the trip and spent years of my life in Russia, I had never been to Siberia, let alone the deepest and most-voluminous lake in the world. The tactile and communicative experiences of being there taught me so many things about Russian nature; many of these understandings are ineffable but I’ll try to articulate some of the ones that I can. While I knew that Baikal and Siberia were big, journeying around by boat and van drove home the enormity of the space. We saw a tiny fraction of Baikal and an even tinier part of Siberia, but their expanses felt endless. The beauty of the Siberian taiga also overwhelmed me and brought an inner tranquility, which I had often read about in historical documents. Yet this firsthand sensation had never subsumed my own psyche so strongly. In the forest I kept stopping to smell the orange-barked coniferous trees around us, which reminded me of the sweet-scented ponderosa pines of the Rocky Mountains. Of course, they did not carry the same aroma. Furthermore, I was surprised to find that the mosquitoes in the area were considerably less ravenous than I had been told to expect. This might have been because of the forest fires nearby or the ample repellent I had applied, but my experience with Siberian mosquitoes certainly varied from what I had read about them. Human interactions also benefited from being on site. I spoke with conservation scientists about both the lake and the practice of nature protection in Russia today. These discussions enriched my perspective on many of the historical conservationists who I have written about previously—not just from what was said but also from how they conveyed it. Meeting with regional experts also opened the door for possible future visits to Lake Baikal. Professors Tatiana and Arkadii Kalikhman from Irkutsk, Aleksandr Ananin at the Barguzin Nature Reserve, and the many scholars in Ulan-Ude who presented their research warmly offered to assist us again on return visits. International collaboration will also continue within the Leverhulme network of multidisciplinary scholars studying Russia’s environmental past. A final trip to the Ural Mountains next summer is in the works and the organizer of the network, David Moon from the University of York, is planning on putting together an edited volume from the papers presented during the traveling workshops. Though I do not anticipate being able to attend future meetings, I do intend to revise my presentation, which I literally gave on a boat on Baikal, about the history of Lake Imandra on the Kola Peninsula into an essay for the collection. Andy Bruno Northern Illinois University