Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Story by C.D. Mannion

advertisement

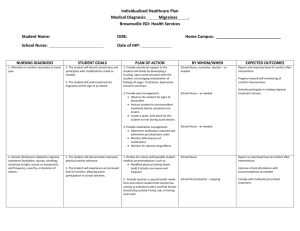

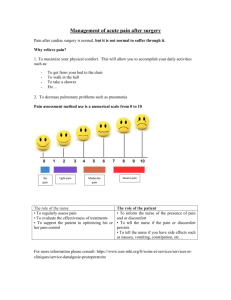

Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Story by:MannionUSMC “Sorry if I'm hurting you,” the nurse says, not seeing the irony behind this being the first time she shows concern for any pain I may feel, but I can hear sincerity in her voice. She is sorry if the removal of my IV and the tape being removed is causing me any pain, when in fact I have been in a severe amount of pain for hours and can't even feel the minor discomfort she is apologizing for. She flinches as she removes my IV. What she fails to apologize for is the treatment I’ve received in the hours I have been in her care. I am no longer in the throes of an attack and am glad the ER is over for today. However, what lingers is the nurse’s apology for removing the tape from my IV. This happens almost every time I go to the ER, and with the exception of a few RNs who know me, I am usually treated horribly every visit too. This is the nature of my illness. I suffer from a condition called Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome (CVS). I experience periods of time—sometimes every few days, sometimes only once or twice a month—where I am extremely sick, vomiting until I require aggressive IV fluids. My severe pain can only be managed by Dilaudid, the one narcotic the Emergency Room despises giving out because of its strength (and the times they failed to monitor their patients while on said medication and it caused medical emergencies). I require anxiety medication because my illness wreaks havoc on my central nervous system, most notably my autonomic nervous system. When treated improperly, this leads to me seizing, and I can get confrontational due to hormonal imbalances from being sick or being postictal from seizing. I have a good GI doctor who knows CVS well, but since he does not work out of my local hospital, the team there is refusing to listen to any advice he has to give on how to treat me. I am always asked by staff, “Why don't you just go to a different hospital already?” when I live two blocks away. Taking an ambulance to another facility (not like they would go to a different hospital if I asked) would take that ambulance out of service until they made it back into town from taking me to a “different hospital.” The facility they most often tell me to go to (the VA clinic in Brick) doesn't even handle emergencies. I live two blocks from this hospital, I have a note from my doctors on how to fix my illness if I present in the ER, I met with the head of the ER about my illness when I first moved back to town—yet I still have to pull teeth to even get them to run fluids properly. My illness is well documented. CVS sometimes goes away, in my case for a month or so, but then it always hits back. Recently the ER had a doctor convince my GP (someone not educated in CVS) that my more frequent ER visits are just a reaction to narcotic withdrawal. After that, he would not let me get a word in. In fact I go quite a while without the ER at times, even though I need help, and any testing of my urine or blood would show that narcotics are not an issue. Currently I have only had two ER attacks in the last 2 months, the last one 2 weeks ago. (I am proud of that, that entire time I had to fight attacks that almost sent me to the ER at home, and was able to abort all but two attacks). My illness can also be treated in the ER in under an hour without fail. With 2 rounds of 1mg of Dilaudid, 2mg of Zofran, 1–2mg of Ativan, and aggressive fluids on a pump, I get better in no time at all. Once the fluids are in (a second bag helps if I have been taking care of attacks at home recently), I can go home. When I get treated with different medication or treated less than human by staff (which is in most cases), then it is much harder for me to break a cycle and get my feet back under me. A look at my ER visit history will show I do not go to maintain an addiction, and I do not show up when I do not require it to treat symptoms of my illness. A visit to my room when I first show up in the ER will prove that I am in a medical emergency (my vitals, if taken, would show the same). Seeing me in the ER when I first arrive would also demonstrate that quick treatment, as recommended by my doctors, is the best way to get me out of an attack. However, my treatment changed after an ER doctor stopped listening to my care plan and talked many people in the ER into doing the same. My cycles were exasperated by the stress of not knowing how the ER would treat me the next time I needed help. I can deal with the horrible staff members (a few of them are wonderful), but I cannot deal with being mistreated while the best solution is ignored. A specialist worked hard to develop a care plan for me, and it is not being taken seriously. I can’t handle how the doctors in the ER have said, “I only used to give you those medications because it was the easiest.” So why would you keep the easiest solution to the problem I am having from me? It sure seems like punishment when they know that my medication cocktail works. During an ER visit a few weeks before that, this same doctor said, “Well it worked the last few times, so of course I will give it to you.” Then his pride or ego gets bruised and he wants to come into my ER room and bully me while I am still sick and then call in 7 security guards in an attempt to make me lose my cool after I had a seizure. (It worked.) I don’t know his side of the story, of course, but that’s mine. We the chronically ill are people too. Even the “drug seekers” you speak of are fewer and further between then you think. It's human nature to gravitate toward looking down on others to feel better about ourselves. We all do it to someone to some degree, but in the case of healthcare workers, they sure feel free to get unprofessional when they determine you are just there for the drugs. Doctors sometimes fail to realize not every patient is the same; you can’t slap a label on somebody and ignore the signs that they need a different kind of help than what you expect. Although some of us may be making pain noises like those they have labeled drug seekers, that does not mean we are there for the narcotics and are not in excruciating pain. I am still a human. I still recognize health care professionals as individual humans, and I need them to do the same for me. I need ER workers to recognize their ethics fatigue and talk to someone about it. I need the nurses who know the best way to deal with me (to keep me updated, treat me as fast as possible, and call the doctor until they actually show up) to help the nurses who they see are making a mess of one of my visits. I must give credit to one nurse in the ER near me; if I am in her pod, even if I am not her patient, she is usually doing everything for the nurse assigned to me. She gets so frustrated by my treatment that she just takes over for them. I need every nurse in that ER to treat me like that one nurse does. I need the ER doctors to understand that I am not there for fun, no one would be there once a month for kicks, no one would be able to “act” out a CVS episode—the vomiting followed by dry heaving and seizing is not something I have ever seen done well on TV or in the movies. I am currently waiting to hear back from the ER vice president about setting up a nursing service to come to my house and give me my medication and fluids when I get sick instead. If this works out, I am sure my number of attacks will drop with the lack of stress of impeding ER torture. I am still not anywhere close to certain that will be approved, though. So for now I am stuck fighting attacks at home and, if need be, calling for a ride to the ER to fight the struggle there. CVS has turned me into a more compassionate person. I was always helpful—before I got sick I was an EMT—but I was nowhere near as empathetic as I am now. There are a lot of worst things people can go through, and now I am grateful for what I have. I still have good days. I still have my sight. I am not locked in my body praying for release. So I count the good in my life, am glad I live in a decade with hot water on tap and that my landlord pays the heat. I try to be good to my support system while out of attack because, during seizures, I tend to yell at everyone (which is not my fault but still leaves me feeling guilty). With chronic illness, it’s easy to get down on yourself for how much of a hassle you are on the people in your life and society in general, but I realized there are still a few things I can do at this moment to be productive to society. Writing this is one example. I am trying to give caretakers and health care providers insight into what it is like to live with Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome. I am hoping to enlighten just one hospital employee to seek care for ethics fatigue, or to change their ways to be more like that one nurse who really watches my back. And if nothing else, I want to let others with CVS know they are not alone.