List of Sources for the 2015 Write-on Competition

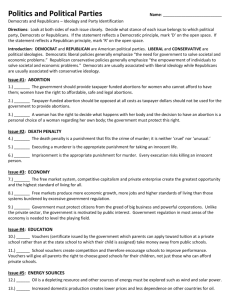

advertisement