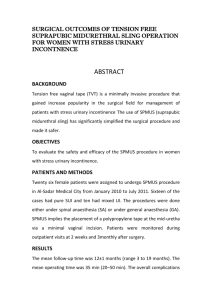

Complications of Synthetic mid

advertisement

Complications of Synthetic mid-Urethral Slings By Christian Twiss, MD and Shlomo Raz, MD Issues in Incontinence: Spring/Summer 2008 Due to its efficacy, safety, and relative simplicity, the synthetic mid-urethral sling procedure has emerged as one of the mainstays of surgical therapy for female stress urinary incontinence. The transobturator approach to placing midurethral slings has recently been marketed as safer than the retropubic approach due to avoidance of entry into the retropubic space. However, accumulated experience has demonstrated that significant complications are possible with both techniques. The purpose of this review is to summarize the rates, etiology, and management of the most common complications encountered with synthetic mid-urethral slings and to compare, based on recent evidence, complication rates of the retropubic and transobturator approaches to sling placement. Bleeding One of the difficulties in assessing bleeding complications of synthetic sling placement is that “bleeding” as a complication has no firm definition or criteria. There is great variability in the literature in reporting and assessing the degree of bleeding, including intraoperative versus postoperative bleeding, bleeding requiring reoperation, bleeding requiring transfusion, hematoma size, volume of blood loss, and major vascular injury. Bleeding can occur from the vaginal incision, from the periurethral dissection, from vessels in the retropubic space, or, in rare cases, from overt injury to the iliac or obturator vessels. When placing retropubic slings, a common source of troublesome bleeding is inadvertent deviation of the trocar within the retropubic space, either too close to the urethra, leading to bleeding from the periurethral venous complex, or too lateral, leading to venous bleeding from vessels on the pelvic sidewall. Careful control of trocar placement reduces the potential for bleeding from these sites. One of the largest series to report bleeding after retropubic placement of syntheticslings is an Austrian registry of 5578 tensionfree vaginal tape (TVT) procedures,1 which showed an overall 2.7% rate of bleeding complications with 0.8% requiring reoperation, primarily via laparotomy. Other large TVT series 2-3 report similar rates of hemorrhage/hematoma, between 1.9% and 2.7%. However, when routine pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed after retropubic sling procedures, 25% of patients were found to have clinically unsuspected retropubic hematomas.4 From these data we can conclude that significant bleeding is possible after retropubic sling placement, albeit that the reported rates in the large studies suggest that major, clinically overt bleeding is uncommon. More recent evidence suggests that bleeding is significantly reduced with the transobturator approach to mid-urethral sling placement. Several large series 5-8 fail to report any significant bleeding complications with the technique. The meta-analysis by Sung et al 9 of randomized controlled trials comparing retropubic with transobturator slings found that the rate of significant hematoma was 1.6% for the retropubic approach compared to 0.08% for the transobturator approach. Similarly, in the recent metaanalysis by Novara et al, 10 the odds ratio of pelvic hematoma was 4.83 for retropubic as compared to transobturator slings. However, despite this evidence, significant bleeding, including iliac and obturator vessel injury, has been reported 11-12 with use of the transobturator technique. Thus, although there is a consensus that transobturator sling procedures carry significantly less bleeding risk compared to retropubic midurethral sling procedures, transobturator sling placements are by no means immune to bleeding complications, and careful attention must be paid to proper technique. Perforations and erosions Perforations occur when the surgeon inadvertently places the sling material into an unwanted anatomical position, typically into the urinary tract (bladder, bladder neck, or urethra) or through the vaginal wall. Perforations are typically considered an intraoperative complication, recognized and corrected at the time of surgery. Erosions are typically detected in the postoperative period when sling material is found in the urinary tract or noted to be exposed in the vagina. While erosions are often considered a postoperative complication, it is important to be cognizant that many postoperative “erosions” are actually the result of undetected perforations that occurred at the time of surgery. Bladder perforation is one of the more common intraoperative problems encountered with retropubic midurethral sling placement, occurring in 2.7%–6% in large series. 2, 13-16 Bladder perforation during retropubic sling placement occurs more commonly in patients with a history of anti-incontinence procedures,13 likely due to scarring within the retropubic space. Bladder perforation occurs less frequently with the transobturator approach compared to the retropubic approach, 9,10,17 with reported rates of bladder perforation between 0% and 1.5% with this technique. 7,9,17,18 However, the majority of bladder perforations, when recognized intraoperatively, are relatively minor complications and are often corrected intraoperatively by repositioning and re-passage of the trocar and sling material,16 typically followed by a period of bladder drainage with a urethral catheter. Urethral perforation remains rare for both retropubic and transobturator approaches, but it can occur with either.2,7,16,19 As opposed to the case of bleeding and bladder perforation, the evidence does not currently suggest that urethral perforation occurs less commonly with the transobturator approach compared to the retropubic approach. Intraoperative urethral injury has been reported in 0.07%–0.2% of retropubic sling cases 2,16 and 0.1%–2.5% of transobturator sling cases.7,20,21 Since the urethra is a high-pressure system, this complication typically requires a formal repair of the damaged area and is somewhat more serious than bladder perforation. After repair, the choice of placing or not placing a sling depends upon the severity of the perforation and the comfort level and judgment of the surgeon. Regardless, as with bladder injury, a period of urethral catheterization is recommended during the healing period. When sling material is found in the urethra in the postoperative period, it is termed a urethral erosion. The risk factors for postoperative urethral erosion include undetected urethral perforation, excessive sling tension, and postoperative urethral dilations.19 Treatment involves removal of the offending material and formal urethral repair. Unfortunately, both in our experience and in that of others, recurrent incontinence (stress and/or urge incontinence) is common after intervention in these cases.19,22 Bowel perforation is a potentially lethal complication that typically occurs when the retropubic approach is utilized in patients with bowel adhesions in the retropubic space due to prior abdominal surgeries. 23,24 Bowel perforation is rare, reported to occur in 0.03%–0.7% of retropubic sling cases. 13,23,24 The risk of this complication is greatly reduced with use of the transobturator approach because it specifically avoids entry into the retropubic space. We agree with other authors that the transobturator approach should be considered in patients who are at particularly high risk for bowel adhesions in the retropubic space. Treatment for bowel perforations is directed at resolving associated sepsis, removal of the sling, and resection and/or repair of the damaged segment of bowel. Postoperative vaginal erosions are another problem with synthetic slings. Metaanalyses 10,17 of randomized trials comparing retropubic with transobturator synthetic slings fail to demonstrate a significant difference in vaginal erosion rates between the two techniques. Large case series 2,23,25,26 of TVT and SPARC-sling procedures report that vaginal erosions are rare, occurring in 0.2%–1.8% of cases. While some authors 27 have suggested slightly higher rates of vaginal erosions with transobturator slings, this may reflect the high erosion rates (6.1%–20%) noted to occur with the Mentor ObTape kit, 2830 which has subsequently been removed from the market. More recently, a large French registry 20 of 984 TVT-O (inside-out transobturator approach for TVT) procedures reported a postoperative vaginal erosion rate of 0.6%, a figure within the range found in the large TVT and SPARC series. These results bring to light that the more important factor in preventing vaginal erosions appears to be choice of synthetic sling material. Soft, woven, monofilament polypropylene mesh with large (> 75 microns) pore size appears to be the mesh of choice, as it allows proper incorporation of the mesh into host tissue and facilitates immune surveillance. 31 Both multifilament meshes and monofilament meshes with small pore sizes allow passage of microbes but not host macrophages, thereby promoting infection and subsequent erosion. 31 Management of vaginal erosions consists of either complete excision of the mesh, excision of the exposed portion of mesh, or observation. While several authors 32-34 have reported on their experience with mesh erosions, there is currently no evidence-based consensus on the management of vaginal erosions. We typically attempt complete mesh removal in cases where the mesh is infected or traverses the urinary tract, the mesh composition (multifilament, small pore size) is unfavorable and likely to reerode or become infected, or the mesh is causing significant pain due to infection or its location. We perform more conservative excision of the exposed area of mesh followed by closure of the vaginal wall in cases where the mesh is uninfected, non-painful, and composed of favorable material. Others 35 have adopted a similar management scheme for vaginal erosions. Some authors 34 have also reported successful conservative observation and spontaneous healing of small, non-infected erosions. Groin and thigh complications Groin and thigh complications are significantly more prevalent with transobturator slings than retropubic slings and can be lifethreatening in some cases. A meta-analysis 17 of randomized controlled trials comparing retropubic with transobturator slings found that the odds ratio of groin/thigh pain was 8.3 for transobturator as compared to retropubic slings, and the large French registry of TVT-O procedures 20 reported a 2.7% rate of residual pain lasting greater than 4 weeks duration. In our experience and in that recently published by others, 36 the groin and thigh pain encountered after transobturator sling placement can in some cases be unrelenting and require sling removal, a challenging task. Such pain can result from the passage of the sling through the adductor brevis, adductor magnus, and gracilis muscles (with subsequent myositis); infection and/or abscess; hematoma; or, rarely, obturator nerve entrapment. 12,37 More significant is that serious infectious complications resulting from transobturator slings have been reported,38 including groin and thigh abscesses, sepsis, and gangrene. Managing groin and thigh complications raises the important issue of “invasiveness” with regard to transobturator slings. While transobturator sling procedures are often marketed as “less invasive” due to avoidance of the retropubic space, one must be cognizant that transobturator slings are placed into an anatomic region that is very difficult to access after the sling is placed. Removal of retropubic slings remains relatively straightforward, especially because urologists and gynecologists are familiar with the anatomy of the retropubic space and urethra. Conversely, removal of a transobturator sling remains challenging because it occupies a deeptissue space that is difficult to access, and the anatomy of this region is far less familiar to pelvic surgeons. Thus, both retropubic and transobturator sling procedures are “invasive,” and each sling carries its own set of problems associated with the anatomic region that it occupies. Postoperative voiding dysfunction Voiding dysfunction after sling placement typically includes postoperative urgency/urge incontinence symptoms and/ or obstructive symptoms. The occurrence of voiding difficulties in the postoperative period highlights the importance of determining and documenting the patient’s voiding pattern prior to surgical intervention. For example, persistent urinary urgency after sling placement is typically not considered a complication whereas de-novo urgency symptoms are considered a complication of the surgical intervention. Recent evidence 17,39 suggests that de-novo urgency after sling placement is relatively common, occurring in 10%–15% of cases; however, the range in the literature 40-43 spans a tenfold difference, from 3.1% to 32%. Recent meta-analyses of randomized trials comparing retropubic to transobturator slings are conflicting. The meta-analysis of Latthe et al 17 suggests that there is no significant difference in de-novo urgency rates with respect to the retropubic as compared to the transobturator approach, whereas the study by Novara et al suggests fewer storage-related lower urinary tract symptoms with the transobturator technique compared to the retropubic. A recent study by Botros et al 42 suggests that transobturator slings may carry a lower rate of de-novo urge incontinence when compared to retropubic slings. One hypothesis 42,44 for this difference in postoperative urgency symptoms is that transobturator slings occupy a more horizontal plane as compared to the U-shape of retropubic slings, thereby making less contact with the urethra, resulting in a reduced incidence of de-novo urgency symptoms; however, the evidence supporting this hypothesis is preliminary. Treatment of de-novo urgency after sling surgery is first directed at ruling out sling erosion into the urinary tract, followed by treatment of urge symptoms including first-line pharmacologic therapy (antimuscarinics) followed by possible second-line therapies (neuromodulation, botulinum toxin) for failures. One must also be mindful that partial obstruction resulting from the sling placement can also result in de-novo urgency symptoms. Thus, a careful history assessing for simultaneous obstructive symptoms (straining, hesitancy, positional voiding, incomplete emptying), examination of the urethra and sling (for evidence of excessive tension or malposition), and urodynamic assessment are important in the evaluation of de-novo urgency symptoms. 45 In cases where obstruction is determined to be the likely cause of de-novo urgency symptoms, intervention to loosen or incise the sling or formal urethrolysis may be required. Success rates for storage-symptom resolution after sling de-obstructing procedures vary widely from 12%–100%, but most studies report success rates in the 75%–85% range. 46 The wide range of success rates may result from the timing of surgical intervention on the obstructing sling; there is evidence 47,48 suggesting that longer periods of obstruction are associated with higher rates of persistent storage symptoms. Postoperative urinary obstruction can be a serious complication after sling surgery, and the incidence remains difficult to assess primarily due to the fact that the diagnosis is not always straightforward. While complete urinary obstruction requiring indwelling or intermittent catheterization is obvious, the diagnosis of partial obstruction can be problematic because obstructive symptoms are often accompanied by urgency symptoms, making the clinical assessment difficult, and because there are no firm urodynamic criteria for diagnosing urinary obstruction in women. We agree with other authors 49 that the single most important element in making the diagnosis is the temporal relationship between the onset of new obstructive voiding symptoms and the sling surgery. These symptoms may or may not be accompanied by some objective evidence of partial obstruction such as elevated postvoiding residual volume. This highlights the importance of defining the patient’s voiding pattern prior to surgery so that postoperative alterations can be recognized. A recent review 39 of the Medicare data on 1356 sling procedures found that within the first postoperative year there was a new diagnosis of obstruction in 7% of cases and treatment for obstruction in 8% of cases. The AUA Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Clinical Guidelines Panel estimated 50 the overall risk of permanent and temporary (< 5 weeks) postoperative urinary retention after sling surgery to be 5% and 8%, respectively. A recent study by Morey et al 51 and two recent metaanalyses 10,17 suggest that obstructive complications are more common after retropubic as compared to transobturator sling procedures; this may reflect the difference in shape of the two types of slings, as discussed above, but this concept is currently unproven. There are multiple etiologies for postoperative urinary obstruction after sling surgery, including excessive sling tension, urethral or bladder-neck perforation, urethral fibrosis, and cystocele with subsequent urethral kinking. Thus, initial management includes careful physical examination of the urethra and vagina, including diagnostic cystoscopy and assessment of urethral mobility and vaginal support. Urinary erosions and vaginal prolapse require appropriate corrective surgery; in patients without these findings, the decision to perform surgical intervention on the sling must next be made. Urodynamic evaluation of cases of suspected obstruction after sling surgery remains controversial, as preoperative urodynamic parameters do not correlate with results of urethrolysis surgery for postoperative obstruction following sling surgery, 52 and there are no firm urodynamic criteria for diagnosing female urinary obstruction. Nonetheless, a high-pressure low-flow pattern noted on urodynamic testing, when coupled with corroborating symptoms, can be invaluable in such cases. Therefore, we routinely perform urodynamic evaluation when assessing suspected post-sling obstruction. Initial management is often conservative, consisting of intermittent self-catheterization and possible alpha-blocker therapy. There is little evidence to guide duration of this treatment, but we agree with other authors 47,48 that early intervention should be undertaken not only due to the distress caused to the patient but also because prolonged obstruction after sling surgery may be associated with increased rates of permanent voiding dysfunction. In our experience and that of others,45 operative intervention is typically required on the sling when urinary retention and/or obstructive symptoms do not resolve within approximately 4 weeks after sling placement; however, other authors 46 suggest a longer waiting period of 12 weeks. Many techniques have been described for treatment of post-sling obstruction. These include slingloosening procedures, midline sling incision, segmental sling excision, and formal urethrolysis. Formal transvaginal or retropubic urethrolysis remains the definitive treatment for sling obstruction, with reported 46 success rates of 65%–93%, and relatively low rates of recurrent stress urinary incontinence in the 0%–19% range.45 A detailed discussion of these techniques is beyond the scope of this review, but the topic has recently been comprehensively reviewed. 46 Recurrent stress incontinence: treatment failure There is currently a paucity of literature on the management of failed suburethral sling procedures. Treatment failures can arise from a number of problems, including technical problems with the sling placement, or from patient-oriented factors such as persistently high intra-abdominal pressures (obesity) or poor urethral tissue quality (radiation, aging). Technical problems with the surgery include sling laxity, poor sling placement (either proximal to the bladder neck or too distally near the meatus), or sling placement into the urethra, which can sometimes lead to simultaneous recurrent stress incontinence and obstructive/irritative symptoms. The first steps in management remain a vaginal exam and cystoscopic evaluation to rule out a major complication (perforation or erosion) and urodynamic evaluation to objectively define the patient’s current voiding pattern as best as possible. Treatment of major complications necessitates appropriate corrective surgery, often involving removal of the sling followed by a period of recovery and reevaluation prior to re-intervention. Options for re-intervention include adjusting (within a few days of original surgery) tension of slings judged to be too lax, performing a tandem sling placement, removing a malpositioned or failed sling with simultaneous placement of a new sling, or using adjuvant urethral injectable therapy. 53,54 The selected option should be based on the suspected cause of the recurrent incontinence; for example, when the urethra appears well supported, we typically administer a urethral bulking agent to augment urethral coaptation, whereas in cases of persistent hypermobility due to sling laxity or poor position, we will perform a secondary sling procedure with or without removal of the extant sling (depending upon its position and composition). Some authors 55 report decreased overall efficacy with a secondary sling as compared to a primary one while others 56 report equivalent efficacy. There is some evidence 55 that, after failure of the primary sling, a secondary retropubic sling may be more efficacious than a secondary transobturator sling. Other authors 54 have reported successful management of failed sling surgery with the use of periurethral bulking agents, but poor durability and incomplete symptom resolution remain problematic with this modality. In our experience, bulking agents are most effective in cases where recurrent incontinence is relatively mild and there is evidence of good urethral support. However, in cases of moderate to severe recurrent incontinence, we typically place either a retropubic polypropylene sling or the UCLA spiral sling with simultaneous transvaginal urethrolysis, as first described by our institution. 57 The latter procedure is especially effective in salvage therapy for patients who have developed a fixed, fibrotic (“pipestem”) urethra after multiple failed procedures, radiation, and/or other major insults to the urethra. Under-reporting of complications Despite that many series report complications with synthetic mid-urethral slings, there is compelling evidence that these complications remain under-reported in the literature. Deng et al 58 recently reviewed the MAUDE (Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience) database and identified 161 major complications that included 39 vascular injuries, 38 bowel injuries, and 10 deaths due to surgical complications of synthetic sling placement. In the same study, the ratio of major to total complications in the MAUDE database as compared to literature review suggested significant under-reporting of major complications resulting from synthetic sling placement. Another recent review 11 of the MAUDE database found similar underreporting of complications of transobturator sling placement. Conclusion Synthetic mid-urethral slings have become mainstream therapy for female stress urinary incontinence. Collective experience has revealed overall good safety and efficacy when proper attention is paid to technique and selection of sling material. However, clinicians must remain aware that significant and even lethal complications are possible despite the minimally invasive nature of synthetic mid-urethral sling placement and that complications of these procedures remain underreported in the literature. While the transobturator approach causes fewer bleeding and visceral perforation complications due to avoidance of the retropubic space, it carries its own set of complications associated with placement into the obturator space, which can pose challenging management problems. Thus, the “best” sling procedure is that which works best in the hands of the individual surgeon, based upon accumulated experience and familiarity with anatomy such that complications can be avoided. While complications are preventable, the recognition that complications can occur even when the procedure is performed by the most experienced hands, coupled with appropriate surveillance and recognition of intraoperative and postoperative complications, is paramount for both patient safety and the ultimate achievement of good surgical outcomes of synthetic midurethral sling procedures. References 1. Kölle D, Tamussino K, Hanzal E, Tammaa A, Preyer O, Bader A, et al. Bleeding complications with the tension-free vaginal tape operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2045-9. 2. Kuuva N, Nilsson CG. A nationwide analysis of complications associated with the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:72-7. 3. Jeffry L, Deval B, Birsan A, Soriano D, Daraï E. Objective and subjective cure rates after tension-free vaginal tape for treatment of urinary incontinence. Urology. 2001;58:702-6. 4. Giri SK, Wallis F, Drumm J, Saunders JA, Flood HD. A magnetic resonance imaging-based study of retropubic haematoma after sling procedures: preliminary findings. BJU Int. 2005;96:1067-71. 5. Neuman M. TVT and TVT-Obturator: comparison of two operative procedures. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;131:89-92. Epub 2006 Apr 18. 6. Laurikainen E, Valpas A, Kivelä A, Kalliola T, Rinne K, Takala T, et al. Retropubic compared with transobturator tape placement in treatment of urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:4-11. 7. Roumeguère T, Quackels T, Bollens R, de Groote A, Zlotta A, Bossche MV, et al. Trans-obturator vaginal tape (TOT) for female stress incontinence: one year follow-up in 120 patients. Eur Urol. 2005;48:805-9. Epub 2005 Aug 31. 8. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, Paraiso MF, Walters MD, Vasavada S, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:611-21. 9. Sung VW, Schleinitz MD, Rardin CR, Ward RM, Myers DL. Comparison of retropubic vs transobturator approach to midurethral slings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:3-11. 10. Novara G, Galfano A, Boscolo-Berto R, Secco S, Cavalleri S, Ficarra V, et al. Complication rates of tension-free midurethral slings in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing tension-free midurethral tapes to other surgical procedures and different devices. Eur Urol. 2008;53:288-308. Epub 2007 Nov 8. 11. Boyles SH, Edwards R, Gregory W, Clark A. Complications associated with transobturator sling procedures. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:19-22. Epub 2006 Mar 28. 12. Atassi Z, Reich A, Rudge A, Kreienberg R, Flock F. Haemorrhage and nerve damage as complications of TVT-O procedure: case report and literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:161-4. Epub 2007 Sep 25. 13. Tamussino KF, Hanzal E, Kölle D, Ralph G, Riss PA; Austrian Urogynecology Working Group. Tensionfree vaginal tape operation: results of the Austrian registry. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(5 Pt 1):732-6. 14. Meschia M, Pifarotti P, Bernasconi F, Guercio E, Maffiolini M, Magatti F, et al. Tension-free vaginal tape: analysis of outcomes and complications in 404 stress incontinent women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12 Suppl 2:S24-27. 15. Abouassaly R, Steinberg JR, Lemieux M, Marois C, Gilchrist LI, Bourque JL, et al. Complications of tensionfree vaginal tape surgery: a multi-institutional review. BJU Int. 2004;94:110-3. 16. Gold RS, Groutz A, Pauzner D, Lessing J, Gordon D. Bladder perforation during tension-free vaginal tape surgery: does it matter? J Reprod Med. 2007;52:616-8. 17. Latthe PM, Foon R, Toozs-Hobson P. Transobturator and retropubic tape procedures in stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review and metaanalysis of effectiveness and complications. BJOG. 2007;114:522-31. Epub 2007 Mar 16. Erratum in: BJOG2007;114(10):1311. 18. Juma S, Brito CG. Transobturator tape (TOT): Two yearfollow-up. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:37-41. 19. Velemir L, Amblard J, Jacquetin B, Fatton B. Urethral erosion after suburethral synthetic slings: risk factors, diagnosis, and functional outcome after surgical management. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008. Jan 18 [Epub ahead of print]. 20. Collinet P, Ciofu C, Costa P, Cosson M, Deval B, Grise P, et al. The safety of the inside-out transobturator approach for transvaginal tape (TVT-O) treatment in stress urinary incontinence: French registry data on 984 women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:711-5. Epub 2008 Jan 15. 21. Costa P, Grise P, Droupy S, Monneins F, Assenmacher C, Ballanger P, et al. Surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence with a trans-obturator-tape (T.O.T.) Uratape: short term results of a prospective multicentric study. Eur Urol. 2004;46:102-6; discussion 106-7. 22. Blaivas JG, Sandhu J. Urethral reconstruction after erosion of slings in women. Curr Opin Urol. 2004;14:335-8. 23. Hodroff MA, Sutherland SE, Kesha JB, Siegel SW. Treatment of stress incontinence with the SPARC sling:intraoperative and early complications of 445 patients. Urology. 2005;66:760-2. 24. Kobashi KC, Govier FE. Perioperative complications: the first 140 polypropylene pubovaginal slings. J Urol. 2003;170:1918-21. 25. Hammad FT, Kennedy-Smith A, Robinson RG. Erosions and urinary retention following polypropylene synthetic sling: Australasian survey. Eur Urol. 2005;47:641-6; discussion 646-7. Epub 2004 Dec 31. 26. Karram MM, Segal JL, Vassallo BJ, Kleeman SD. Complications and untoward effects of the tensionfree vaginal tape procedure. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 Pt 1):929-32. 27. Marsh F, Rogerson L. Groin abscess secondary to trans obturator tape erosion: case report and literature review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:543-6. 28. Roth CC, Winters JC, Woodruff AJ. What’s new in slings: an update on midurethral slings. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:242-7. 29. Yamada BS, Govier FE, Stefanovic KB, Kobashi KC. High rate of vaginal erosions associated with the mentor ObTape. J Urol. 2006;176:651-4; discussion 654. 30. Giberti C, Gallo F, Cortese P, Schenone M. Transobturator tape for treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: objective and subjective results after a mean follow-up of two years. Urology. 2007;69:703-7. 31. Feifer A, Corcos J. The use of synthetic sub-urethral slings in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1087-95. Epub 2007 Apr 27. 32. Sweat SD, Itano NB, Clemens JQ, Bushman W, Gruenenfelder J, McGuire EJ, et al. Polypropylene mesh tape for stress urinary incontinence: complications of urethral erosion and outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2002;168:144-6. 33. Clemens JQ, DeLancey JO, Faerber GJ, Westney OL, Mcguire EJ. Urinary tract erosions after synthetic pubovaginal slings: diagnosis and management strategy. Urology. 2000;56:589-94. 34. Kobashi KC, Govier FE. Management of vaginal erosion of polypropylene mesh slings. J Urol. 2003;169:2242-3. 35. Deval B, Haab F. Management of the complications of the synthetic slings. Curr Opin Urol. 2006;16:240-3. 36. Wolter CE, Starkman JS, Scarpero HM, Dmochowski RR. Removal of transobturator midurethral sling for refractory thigh pain. Urology. 2008. Feb 29 [Epub ahead of print] 37. DeSouza R, Shapiro A, Westney OL. Adductor brevis myositis following transobturator tape procedure: a case report and review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:817-20. Epub 2007 Feb 15. 38. Karsenty G, Boman J, Elzayat E, Lemieux MC, Corcos J. Severe soft tissue infection of the thigh after vaginal erosion of transobturator tape for stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:207-12. Epub 2006 May 24. 39. Anger JT, Litwin MS, Wang Q, Pashos CL, Rodríguez LV. Complications of sling surgery among female Medicare beneficiaries. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:707-14. 40. Nilsson CG, Kuuva N. The tension-free vaginal tape procedure is successful in the majority of women with indications for surgical treatment of urinary stress incontinence. BJOG. 2001;108:414-9. 41. Chêne G, Amblard J, Tardieu AS, Escalona JR, Viallon A, Fatton B, et al. Long-term results of tensionfree vaginal tape (TVT) for the treatment of female urinary stress incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;134:87-94. Epub 2006 Aug 7. 42. Botros SM, Miller JJ, Goldberg RP, Gandhi S, Akl M, Beaumont JL, et al. Detrusor overactivity and urge urinary incontinence following trans obturator versus midurethral slings. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:425. 43. Doo CK, Hong B, Chung BJ, Kim JY, Jung HC, Lee KS, et al. Five-year outcomes of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure for treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2006;50:333-8. Epub 2006 May 2. 44. Whiteside JL, Walters MD. Anatomy of the obturator region: relations to a trans-obturator sling. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15:223-6. 45. Gomelsky A, Nitti VW, Dmochowski RR. Management of obstructive voiding dysfunction after incontinence surgery: lessons learned. Urology. 2003;62:391-9. 46. Starkman JS, Scarpero H, Dmochowski RR. Methods and results of urethrolysis. Curr Urol Rep. 2006;7:384-94. 47. Leng WW, Davies BJ, Tarin T, Sweeney DD, Chancellor MB. Delayed treatment of bladder outlet obstruction after sling surgery: association with irreversible bladder dysfunction. J Urol. 2004;172(4 Pt 1):1379-81. 48. Leng WW, Chancellor MB. Recognition and treatment of bladder outlet obstruction after sling surgery. Rev Urol. 2004;6:29-33. 49. Carr LK, Webster GD. Voiding dysfunction following incontinence surgery: diagnosis and treatment with retropubic or vaginal urethrolysis. J Urol. 1997;157:821-3. 50. Leach GE, Dmochowski RR, Appell RA, Blaivas JG, Hadley HR, Luber KM, et al. Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1997;158(3 Pt 1):875-80. 51. Morey AF, Medendorp AR, Noller MW, Mora RV, Shandera KC, Foley JP, et al. Transobturator versus transabdominal mid urethral slings: a multi-institutional comparison of obstructive voiding complications. J Urol. 2006;175(3 Pt 1):1014-7. 52. Nitti VW, Raz S. Obstruction following antiincontinence procedures: diagnosis and treatment with transvaginal urethrolysis. J Urol. 1994;152:93-8. 53. Appell RA, Davila GW. Treatment options for patients with suboptimal response to surgery for stress urinary incontinence. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:285-92. 54. Scarpero HM, Dmochowski RR. Sling failures: what’s next? Curr Urol Rep. 2004;5:389-96. 55. Lee KS, Doo CK, Han DH, Jung BJ, Han JY, Choo MS. Outcomes following repeat mid urethral synthetic sling after failure of the initial sling procedure: rediscovery of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure. J Urol. 2007;178(4 Pt 1):1370-4; discussion 1374. Epub 2007 Aug 16. 56. Rardin CR, Kohli N, Rosenblatt PL, Miklos JR, Moore R, Strohsnitter WC. Tension-free vaginal tape: outcomes among women with primary versus recurrent stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 Pt 1):893-7. 57. Rutman MP, Deng DY, Shah SM, Raz S, Rodríguez LV. Spiral sling salvage anti-incontinence surgery in female patients with a nonfunctional urethra: technique and initial results. J Urol . 2006;175:1794-8; discussion 1798-9. 58. Deng DY, Rutman M, Raz S, Rodriguez LV. Presentation and management of major complications of midurethral slings: Are complications under-reported? Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:46-52.