Images of Noble, Vanishing or Dying Indians

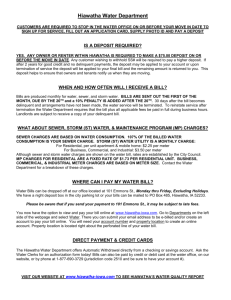

advertisement

English 4125: Colonial and Early American Literature Noble, Vanishing, and Dying Indians in Art and Literature ____________________________________________________________________________ Epigraph: Wallace Stevens, “Sunday Morning” Death is the mother of beauty, mystical, Within whose burning bosom we devise Our earthly mothers waiting, sleeplessly. QUESTION: What is the effect of making Indians themselves, especially dying, vanishing, or “last” Indians (as well as their archeological remnants) objects of aesthetic contemplation or objects of art? “Aesthetics of genocide?” 1) The Noble Indian/Savage “Hiawatha,” by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (American, 1848-1907). Metropolitan Museum of Art. The inspiration for this full-size seated nude was drawn from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's epic poem The Song of Hiawatha (1855), a popular wellspring of themes for American artists during the late nineteenth century. Saint-Gaudens represented the central protagonist, a Chippewa chief, as a contemplative figure seated on a rack, leaning against a tree trunk with his quiver of arrows and bow nearby, and "Pondering, musing in the forest / On the welfare of his people," as the excerpt from Longfellow's poem inscribed on the marble base declares. Omahaw, War Eagle, Little Missouri, and Pawnees, 36 1/8″ x 28″, oil (1821), National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC. Charles Bird King, Young Charles Bird King, Red Jacket, c. 1828. National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC. 2) The Wounded, Dying, or Vanishing Indian “Dying Gaul.” Capitoline Museum, Rome. Peter Stephenson (American, 1823-1861), Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA “The Wounded Indian may be the most beautiful and affecting work in the Chrysler's Ricau collection of American neoclassical sculpture. Apart from its historical significance, which is formidable, this life-size figure of a dying warrior embodies grace and dignity, and evokes empathy and a sense of loss.” Of unmatched importance as an icon of American culture, the Native American's representation has been both rich and contradictory. From the 1820s to 1840s Thomas Cole used Indians as romantic, poetic symbols of a lost past, while artist-explorers George Catlin and Karl Bodmer stressed ethnographic accuracy. Charles Bird King's famous portraits of Native Americans are considered the most complete expression of the idea of the Noble Savage in American art: King's contemporaries compared his sitters to ancient Romans, citing their nobility, intelligence, and character (see object 58.85.1). Concurrent with Western expansion, what some historians call "the myth of the vanishing Indian" developed as a corollary to Manifest Destiny. This racially based theory held that once Native Americans were exposed to European culture their extinction was inevitable; as a primitive people they were doomed whether white men bore arms against them or not. This myth was easily assimilated into nineteenth-century art and literature. In Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1855 poem The Song of Hiawatha, the Indians, weakened and quarreling, are scattered westward, and after blessing the arrival of the white men, Hiawatha paddles peacefully into the hereafter. As Brian Dippe has explained, the Indian's "vanishing" was cause for both celebration and sorrow: proponents of expansion applauded progress but lamented the loss of an unspoiled America. By the mid1850s, two visual expressions of these sentiments had become established. In landscape painting, the Indian appeared on a promontory overlooking a cultivated, urbanizing landscape (see object 71.729). In sculpture, a chieftain or warrior, based loosely on the classical Dying Gaul, stoically met death. Asher Durand, “Advance of Civilization.” 1853