Background Notes and Resources for Teachers The depiction of

advertisement

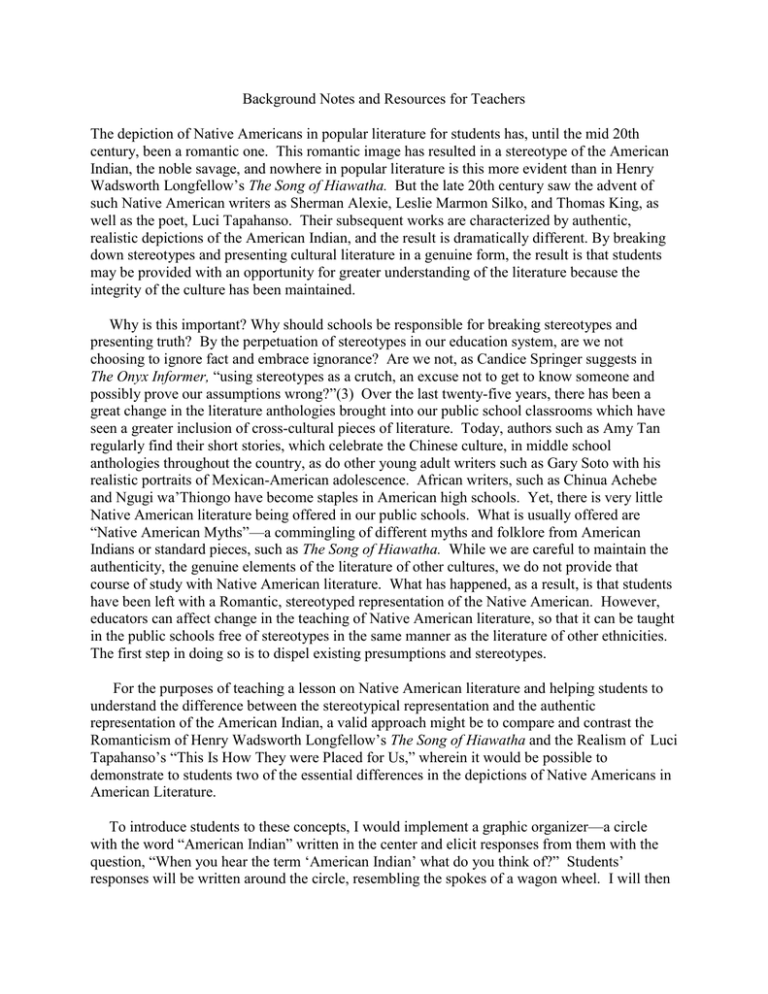

Background Notes and Resources for Teachers The depiction of Native Americans in popular literature for students has, until the mid 20th century, been a romantic one. This romantic image has resulted in a stereotype of the American Indian, the noble savage, and nowhere in popular literature is this more evident than in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha. But the late 20th century saw the advent of such Native American writers as Sherman Alexie, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Thomas King, as well as the poet, Luci Tapahanso. Their subsequent works are characterized by authentic, realistic depictions of the American Indian, and the result is dramatically different. By breaking down stereotypes and presenting cultural literature in a genuine form, the result is that students may be provided with an opportunity for greater understanding of the literature because the integrity of the culture has been maintained. Why is this important? Why should schools be responsible for breaking stereotypes and presenting truth? By the perpetuation of stereotypes in our education system, are we not choosing to ignore fact and embrace ignorance? Are we not, as Candice Springer suggests in The Onyx Informer, “using stereotypes as a crutch, an excuse not to get to know someone and possibly prove our assumptions wrong?”(3) Over the last twenty-five years, there has been a great change in the literature anthologies brought into our public school classrooms which have seen a greater inclusion of cross-cultural pieces of literature. Today, authors such as Amy Tan regularly find their short stories, which celebrate the Chinese culture, in middle school anthologies throughout the country, as do other young adult writers such as Gary Soto with his realistic portraits of Mexican-American adolescence. African writers, such as Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa’Thiongo have become staples in American high schools. Yet, there is very little Native American literature being offered in our public schools. What is usually offered are “Native American Myths”—a commingling of different myths and folklore from American Indians or standard pieces, such as The Song of Hiawatha. While we are careful to maintain the authenticity, the genuine elements of the literature of other cultures, we do not provide that course of study with Native American literature. What has happened, as a result, is that students have been left with a Romantic, stereotyped representation of the Native American. However, educators can affect change in the teaching of Native American literature, so that it can be taught in the public schools free of stereotypes in the same manner as the literature of other ethnicities. The first step in doing so is to dispel existing presumptions and stereotypes. For the purposes of teaching a lesson on Native American literature and helping students to understand the difference between the stereotypical representation and the authentic representation of the American Indian, a valid approach might be to compare and contrast the Romanticism of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha and the Realism of Luci Tapahanso’s “This Is How They were Placed for Us,” wherein it would be possible to demonstrate to students two of the essential differences in the depictions of Native Americans in American Literature. To introduce students to these concepts, I would implement a graphic organizer—a circle with the word “American Indian” written in the center and elicit responses from them with the question, “When you hear the term ‘American Indian’ what do you think of?” Students’ responses will be written around the circle, resembling the spokes of a wagon wheel. I will then tell them that what they are responding to is really a stereotype—that there is no prototypical Native American; rather, the American Indian is made up of different cultures and subcultures with distinct differences in language, clothes, culture, and even homes. To underscore this, I would then show a picture of a hogan and a picture of a wigwam and explain their respective Native American roots. Then I would ask the question, “What do you know about Native Americans in popular culture?” This should provide further evidence of stereotyping, from Disney’s Little Hiawatha and Pocahontas to Tonto and even P.L. Travers’ Mary Poppins. Then, to provide frontloading, I would introduce the following information for students: that The Song of Hiawatha is an epic poem, written in 1855 by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and that for many years it has held a certain esteemed place as a literary piece representative of the Romantic Movement and a literary piece that represents the idealized Native American. To underscore the preceding, I would introduce the poem through the use of The Frederick Remington Illustrated Edition: The Song of Hiawatha, with its “387 Illustration of Indian artifacts” (cover). I would choose this edition because of the illustrations which will help to provide visuals to explain the point at hand and because Remington (1861-1909), who was the most successful Western illustrator at the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th Century, and whose depiction of the American Indian is, and remains, highly stylized and with a great attention to detail, was more interested in, as Longfellow was, a general representation of the American Indian and not a specific tribe: “the full page photogravures are designed by Mr. Remington to serve directly as accompaniments to the poem, and he has followed the poet in using a certain freedom of treatment” (x). By “freedom of treatment” I read “stereotype,” an indulging of a general, inauthentic iconography as opposed to any loyalty to a particular tribe. The anonymous editor’s following comment confirms this: “Mr. Longfellow was more careful of the Indian type than exact in a consistent portraiture of one personage, and used his imagination to emphasize the central truths of his poetic interpretations of Indian life, rather than sought to follow scrupulously the lines of the archaeologist,” and as a result, “his long and close stud[ies] of the Indian in many situations . . . sometimes are fanciful in their treatment” (x-xi). By demonstrating this through the use of the illustrations, students will be further introduced to the notion of the stereotyped and generalized treatment and depiction of Native Americans. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) was a professor at Harvard who believed that being a teacher hindered his writing as it was “a great hand laid on all the strings of my lyre, stopping their vibration” (Oxford Companion 443). As a result, he resigned in 1854 to devote himself to his poetry. In June of 1854, Longfellow began writing The Song of Hiawatha. Longfellow based his poem on Ojibwa/Chippewa folktales and stories as well as those of other Native American peoples such as the Iroquois, Huron, and Delaware tribes in Algic Researches, a collection by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1793-1864), an American explorer and ethnologist of Native American culture, as well as the writings of George Caitlin, a traveler who wished to record the culture of the American Indians before they disappeared, and John Heckewelder, a missionary whose writings about the Delaware and Huron tribes served to inspire the likes of James Fenimore Cooper. And, while the name of Hiawatha is taken from the true life Iroquois chief who helped form the Iroquois Confederacy, the protagonist of The Song of Hiawatha shares a commonality in name only. Unlike Schoolcraft, who broke down his stories of the Algic/North American Indians into such subgroups as Ottawa, Ojibwa, Sioux, Saginaw, Algonquin, and Chippewa, there is, for Longfellow, a blend of Native Americans in his poem; the tribes are indistinct from one another; but he has created his romanticized version of the American Indian, that includes all of them, rather than any specific Native American subgroup. This is borne out in Schoolcraft’s The Myth of Hiawatha, and Other Oral Legends, Mythologic and Allegoric, of the North American Indians in which he states that the myth of Hiawatha “is one of the most general in the Indian country” (13) and that “the prevalence of this legend, among the Indian tribes, is extensive. . . . Longfellow has given prominence to it, and its chief episodes, by selecting and generalizing such traits as appeared best susceptible of poetic uses” (25). It is a perpetuation of an “American Indian Culture,” when, in truth, no such thing exists. The Song of Hiawatha begins with a bibliography concerning the musician Navadaha, who regales this story as it was told him by the animals of the forest. Broken into 23 cantos, it is essentially a tale about the Great Spirit, Gitche Manito, a name taken from the Saginaw or Chippewa, (Schoolcraft Algic Researches 165), who, disturbed by the incessant quarrelling of his people, the American Indians, promises to send them a counselor and prophet of peace. The tale continues with the birth of Hiawatha; Hiawatha’s fight with his father, Mudjekeewis, the West Wind and ruler of all the winds; and his marriage to Minnehaha, up to the advent of the White Man and the death of Hiawatha. To provide additional foundation for students, I would then explain how The Song of Hiawatha stands very much as a prime example of the Romanticism movement of the 18th and 19th centuries with its “primitivism and cult of the ‘noble savage’” (Oxford Companion 651); for, indeed, the very notion of the “noble savage” arose during the Romantic movement—a character untainted by civilization, who lives closer to nature in a simpler, more primitive state. In addition, the popularity of the epic poem did much to bring into American literature those themes in Romanticism of power, imagination, and originality, perpetuating the stereotype of the American Indian as the “Noble Savage” in American literature (and the arts) well into the 20th century. Having once established the concept of the Romantic Movement and The Song of Hiawatha, I would, then, front-load information about the Dine’ (Navajo) culture. To do this, I would employ the use of Navajo ABC/A Dine’ Alphabet Book by Luci Tapahonso and Eleanor Schrick. The purpose for using the picture/Alphabet book would be similar to the use of the Frederic Remington—to provide visuals that would help to support the understanding of stereotype and genuine. Using the Navajo ABC A Dine’ Alphabet Book would provide students with the opportunity to acknowledge specific artifacts belonging to a specific Native American tribe, as opposed to general artifacts belongs to the stereotypical Native American. Emphasis would, then, be placed on the importance of the number 4 and on the character of Changing Woman. I would provide students with biographical information about Luci Tapahanso, contrasting the biographies of Longfellow and Tapahanso, with the use of a T chart, so that students can see the differences between Tapahanso (born 1953), a Native American of the Dine’ (Navajo) culture, who was born and raised on a Navajo reservation in New Mexico and who initially spoke her native Dine’ language instead of English, and how her stories and poems reflect that, with their rich use of the authentic words and phrases, which in turn mark the history of her culture. I would further explain that it is from the history of her culture that she gains her sense of identity: “Wrapped in blankets and looking at the stars, a Navajo girl listened long ago to stories that would guide her for the rest of her life. Such summer evenings were filled with quiet voices, dogs barking far away, the fire crackling, and often we could hear the faint drums and songs of a ceremony somewhere in the distance” (Blue Horses back cover). We would then read the poem, “This is How They Were Placed for Us.” “This is How They Were Placed for Us” tells the story of Changing Woman, a seminal figure in Navajo culture, who teaches values in the bearing and raising of children and the importance of family and family relationships. Through the poem, the significance of the matrilineal system is clearly defined, a system which continues to influence modern day Dine’ values and responsibilities. This, in turn, underscores the Realism of Tapahanso’s poem through its use of authentic language and its meter and rhythm which provides a sense of ceremony; its use of the geographical landscape of the mountains which represents the parameters of the Dine’ world; and its matrilineal lineage which defines the identity of the Dine’ people. In doing so, it provides a link for “the over one hundred clans today” with those “first four clans created by Changing Woman” (“Luci Tapahonso . . .Poet”): Because of her, we think and create. Because of her, we make songs. Because of her, the designs appear as we weave. Because of her, we tell stories and laugh. We believe in old values and new ideas (Blue Horses 39). By comparing and contrasting the backgrounds and source materials for both poems, it should be readily apparent that Longfellow’s poem is firmly entrenched thematically and philosophically in the Romanticism of American Literature with its espousal of themes characteristic of the Romantic Movement: primitivism, the “Noble Savage,” power, imagination, and originality, and its use of diverse and undifferentiated source material have created a general picture of the Native American, an American Indian. In contrast, Tapahanso’s poem employs the use of authentic Navajo/Dine’ tradition, folklore, and culture “because the past determines what our present is or our future will be. I don’t think there is a separation of the three . . . this land that may seem arid and forlorn to the newcomer is full of stories which hold the spirits of the people, those who live here today and those who lived centuries and other worlds ago” (“Lucy Tapahonso . . .Poet). Although her poetry is modern, Tapahanso’s sensibilities are born and remain a part of the Dine’ tradition. This should help students to identify and define the difference between the inauthentic and the authentic. To further and better understand how this background comes into play in the poems, focus should be placed on the importance of the number 4 in both works. The point of the number 4 demonstrates the contrast between Longfellow’s use of it as strictly a plot device and Tapahanso’s use of the number as an element of cultural identity. For this, students will implement a Venn Diagram, with the center overlapping section containing the number 4—the only element common to both poems. In The Song of Hiawatha, Longfellow’s use of the number 4 is demonstrated in Canto II, entitled “The Four Winds.” In this Canto, influenced by Schoolcraft’s retelling of the Ojibwa tale, “Puck Wudj Ininee” (Algic Researches 90), Mudjekeewis, the father of Hiawatha, defeats “the Great Bear of the Mountains” (The Song of Hiawatha 14) and becomes the ruler of the Four Winds. There is no mysticism or spiritualism involved; for Longfellow it is a plot device to set up Canto IV, wherein Hiawatha confronts Mudjekeewis about his father’s culpability in the death of Hiawatha’s mother Wenonah, and an opportunity for character development, and we see once again a perpetuation of the Romantic notion of the “Noble Savage”: Patiently sat Hiawatha Listening to his father's boasting; With a smile he sat and listened, Uttered neither threat nor menace Neither word not look betrayed him, But his heart was hot within him, Like a living coal his heart was (39). Once again, we see a perpetuation of the Romantic notion of primitivism in the simple and unsophisticated behavior of the “Noble Savage,” because Hiawatha, a member of an uncivilized race, behaves in a way that might be characterized as innately good: “Patiently sat Hiawatha,/Listening to his father’s boasting;/With a smile he sat and listened,/Uttered neither threat or menace;” dignified: “Neither word nor look betrayed him;” and noble” “But his heart was hot within him,/Like a living coat his heart was.” The significance of the number 4 is actually insignificant due to Longfellow’s general approach in creating an American Indian culture; this is directly at variance with Tapahanso, whose approach and use of the number 4 delineates a greater understanding of the Dine’ traditions and beliefs—a specific Native American culture. Tapahanso’s multi-faceted use of the number 4 demonstrates it to be an element of inter-relationship in the poem, bringing together identity; tradition; the present, past, and future; as well as the poem’s structure and literal and metaphorical. In the Dine’ tradition, the element of number 4 has a mystical, spiritual quality: there are 4 main colors (black, yellow, blue, and white), 4 mountains which provide the demarcation of the Dine’ world (Mt. Taylor, Mt. Hesperus, San Francisco Peaks and Blanca Peak), 4 cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west), 4 seasons (spring, summer, fall, and winter), 4 times of day (night, dawn, day, dusk), 4 beliefs (speak, think, sing, pray), 4 stages of life (birth, childhood, adulthood, old age), and 4 worlds (fire, breath, water, reemergence). A further comparison and contrast between the two poems may be seen through the use of their respective “protagonists.” In Longfellow’s poem, Hiawatha is the idealized epic hero, morally and physically strong, bigger and braver than anyone, able to defeat monsters; in Tapahanso’s poem, Changing Woman is symbolic of the more realistic and down-to-earth values of the Dine’, associated with of child bearing, child rearing, family values, and familial expectations and relationships. Finally, the Romanticism of The Song of Hiawatha may be seen in Hiawatha’s role as a bridge between Native Americans and Whites and his acceptance of the intrusion of the White Man into Native American culture as a good and natural progression; this optimism is also a part of the Romantic Movement of the 19th century, as opposed to the grounded Realism of the retention of values, customs, and the land to keep one strong with Changing Woman. In conclusion, to understand the Realism of Tapahanso, one must retain the Romanticism of Longfellow. Consequently, both works are important in terms of American Literature and in their respective representations of the Native American, and by retaining both in the classroom they will provide for a comprehensive study allowing students to break the stereotype set forth by the Romantic and recognize the authentic representation set forth by the Realistic. Works Cited Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. The Song of Hiawatha: The Frederic Remington Illustrated Edition. 1890. New York: Bounty Books, 1968. Print. “Luci Tapahonso: Native American Poet.” Native American Authors. Native Authors.com. Web. 19 Oct 2012. American The Oxford Companion to American Literature. Fifth Edition. Ed. James D. York: Oxford University Press, 1983. Print. Hart. New Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Algic Researches. 1839. Carlisle, MA: Applewood Print. Books, 2011. Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. The Myth of Hiawatha and other Oral Legends, Mythologic and Allegoric, of the North American Indians. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1856. 1-142. Project Gutenberg. Web. 2 Nov 2012. Springer, Candice. “Wisdom for the Ages.” The Onyx Informer. Feb 08: 3. Google. Web. 11 Nov 2012. Tapahonso, Luci. Blue Horses Rush In. Tuscon: The University of Arizona Print. Tapahonso, Luci and Eleanor Schick. Navajo ABC A Dine’ Alphabet Book. and Shuster, 1995. Print. Press, 1988. New York: Simon