Downloaded - DORAS

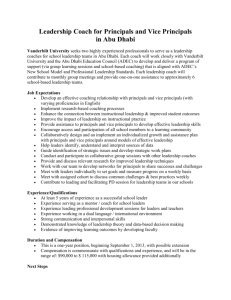

advertisement