Relations and Functions in Mathematics

advertisement

Relations

What is a Relation?

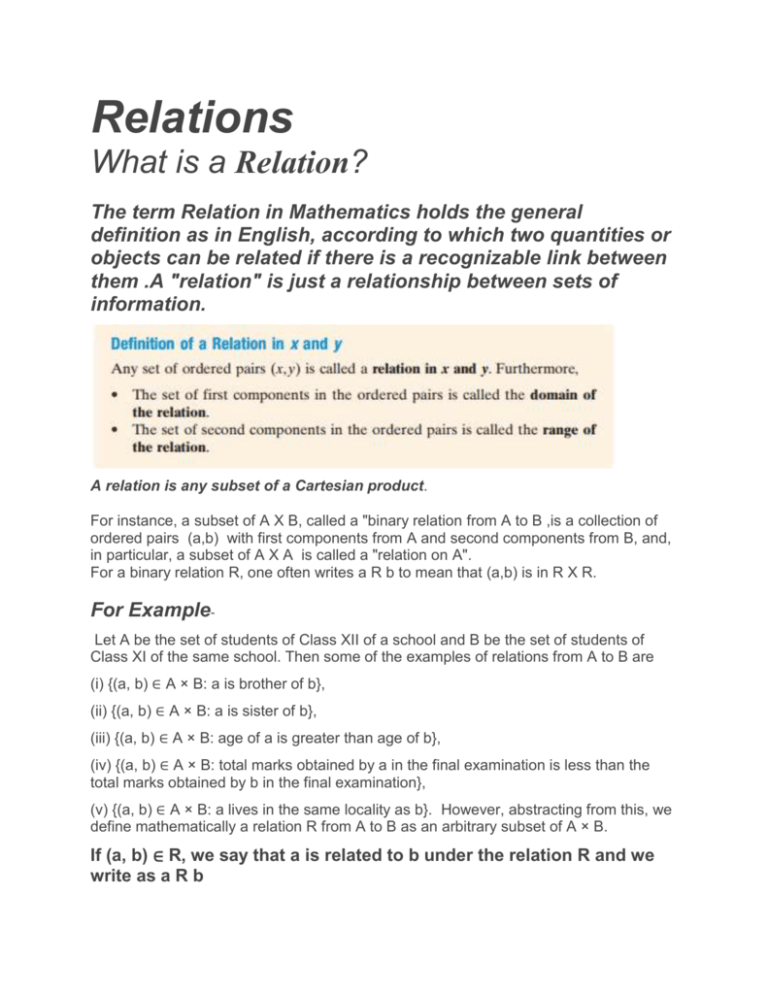

The term Relation in Mathematics holds the general

definition as in English, according to which two quantities or

objects can be related if there is a recognizable link between

them .A "relation" is just a relationship between sets of

information.

A relation is any subset of a Cartesian product.

For instance, a subset of A X B, called a "binary relation from A to B ,is a collection of

ordered pairs (a,b) with first components from A and second components from B, and,

in particular, a subset of A X A is called a "relation on A".

For a binary relation R, one often writes a R b to mean that (a,b) is in R X R.

For ExampleLet A be the set of students of Class XII of a school and B be the set of students of

Class XI of the same school. Then some of the examples of relations from A to B are

(i) {(a, b) ∈ A × B: a is brother of b},

(ii) {(a, b) ∈ A × B: a is sister of b},

(iii) {(a, b) ∈ A × B: age of a is greater than age of b},

(iv) {(a, b) ∈ A × B: total marks obtained by a in the final examination is less than the

total marks obtained by b in the final examination},

(v) {(a, b) ∈ A × B: a lives in the same locality as b}. However, abstracting from this, we

define mathematically a relation R from A to B as an arbitrary subset of A × B.

If (a, b) ∈ R, we say that a is related to b under the relation R and we

write as a R b

Types of Relations

Empty Relations

Universal Relations

Identity Relation

Empty Relation

A relation R in a set A is called empty relation, if no element of A is related

to any element of A, i.e., R = φ ⊂ A × A.

Universal Relation:

A relation R in a set A is called universal relation, if each element of A is

related to every element of A, i.e., R = A × A.

Identity Relation

The identity relation is true for all pairs whose first and second element are

identical ,i.e., R= { (x,x)| x∈ A} ⊂ A x A

EXAMPLE

All these relations are definitions of the relation "likes" on the set {Ann, Bob, Chip}.

Happy world

In this world, "likes" is the full relation on the universe. Because it is full, every person

likes every other person, including him- or herself. The extension of this "likes" relation

is {(Ann,Ann),(Ann,Bob),(Ann,Chip),(Bob,Ann),(Bob,Bob),(Bob,Chip),

(Chip,Ann),(Chip,Bob),(Chip,Chip)}.

Narcissistic world

In this world, "likes" is the identity relation on the universe. Because it is the identity

relation, every person likes him- or herself, but no one else. The extension of this

"likes" relation is {(Ann,Ann),(Bob,Bob),(Chip,Chip)}.

Emptily unhappy world

In this world, "likes" is the empty relation. Because it is empty, no person likes any

other person, including him- or herself. The extension of this "likes" relation is { }.

A relation R in a set A is said to be an equivalence relation if R is

reflexive, symmetric and transitive

Examples using Ann, Bob, and Chip:

Happy world

"likes" is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. (It is an equivalence relation.)

Narcissistic world

"likes" is reflexive, symmetric, antisymmetric, and transitive. (It is both an

equivalence relation and a non-strict order relation, and on this world

produces an antichain.)

Emptily unhappy world

"likes" is not reflexive, and is trivially irreflexive, symmetric, antisymmetric,

and transitive.

Circularly unhappy world

This world's extension of "likes" is {(Ann,Bob),(Bob,Chip),(Chip,Ann)}.

"likes" is irreflexive, antisymmetric, and not transitive.

Somewhat-happy world with 2-circuit

This world's extension of "likes" is {(Ann,Bob),(Bob,Ann),(Chip,Chip)}.

"likes" is neither reflexive nor irreflexive, but is both symmetric and

transitive..

Happy world with 2-circuit

This world's extension of "likes" is

{(Ann,Ann),(Ann,Bob),(Bob,Ann),(Bob,Bob),(Chip,Chip)}. "likes" is

reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.. (It is an equivalence relation.)

Functions

How to identify a Function?

A Function is a special set of Relation , which has

only one range value for each domain.

Types of Function:

Injective

Surjective

A function f : X → Y is defined to be one-one (or injective), if the

images of distinct elements of X under f are distinct, i.e., for

every x1, x2 ∈ X, f(x1) = f(x2) implies x1 = x2. Otherwise, f is

called many-one.

The function f1 and f4 in Fig 1.2 (i) and (iv) are one-one and the

function f2 and f3 in Fig 1.2 (ii) and (iii) are many-one.

A function f : X → Y is said to be onto (or surjective), if every

element of Y is the image of some element of X under f, i.e., for

every y ∈ Y, there exists an element x in X such that f(x) = y.

The function f3 and f4 in Fig 1.2 (iii), (iv) are onto and the

function f1 in Fig 1.2 (i) is not onto as elements e, f in X2 are not

the image of any element in X1 under f1.

Composition of Functions and Invertible Function

Composition of Functions

Let f : A → B and g : B → C be two functions. Then the composition of f and g,

denoted by gof, is defined as the function gof : A → C given by gof(x) = g(f(x)), ∀ x

∈ A.

Invertible Function

A function f : X → Y is defined to be invertible, if there exists a function g : Y →

X such that gof = IX and fog = IY. The function g is called the inverse of f and is

denoted by f -1.

Thus, if f is invertible, then f must be one-one and onto and

conversely, if f is one-one and onto, then f must be invertible.

This fact significantly helps for proving a function f to be invertible

by showing that f is one-one and onto, specially when the actual

inverse of f is not to be determined.

Binary Operations

A binary operation ∗ on a set A is a function ∗ : A × A → A. We

denote ∗ (a, b) by a ∗ b

1. A binary operation ∗ on the set X is called commutative, if a ∗ b = b ∗ a, for every

a, b ∈ X.

Since a + b = b + a and a × b = b × a, ∀a, b ∈ R, ‘+’ and ‘×’ are commutative

binary operation.

However, ‘–’ is not commutative, since 3 – 4 ≠ 4 – 3. Similarly, 3 ÷ 4 ≠ 4 ÷ 3

shows that ‘÷’ is not commutative

2. A binary operation ∗ : A × A → A is said to be associative if (a ∗ b) ∗ c = a ∗ (b ∗

c), ∀a, b, c, ∈ A.

Addition and multiplication are associative, since (a + b) + c = a + (b + c) and

(a×b) × c = a × (b × c) ∀ a, b, c ∈ R.

However, subtraction and division are not associative, as (8 – 5) – 3 ≠ 8 – (5 – 3)

and (8 ÷ 5) ÷ 3 ≠ 8 ÷ (5 ÷ 3)

3. Given a binary operation ∗ : A × A → A, an element e ∈ A, if it exists, is called

identity for the operation ∗, if a ∗ e = a = e ∗ a, ∀ a ∈ A.

a + 0 = 0 + a = a and a × 1 = a = 1 × a, ∀a ∈ R implies that 0 and 1 are identity

elements for the operations ‘+’ and ‘×’ respectively.

Further, there is no element e in R with a – e = e – a, ∀a. Similarly, we can not

find any element e in R, such that a ÷ e = e ÷ a, ∀a in R∗. Hence, ‘–’ and ‘÷’ do

not have identity element.

4. Given a binary operation ∗ : A × A → A with the identity element e in A, an

element a ∈ A is said to be invertible with respect to the operation ∗, if there

exists an element b in A such that a ∗ b = e = b ∗ a and b is called the inverse of

a and is denoted by a-1.

As a + (– a) = a – a = 0 and (– a) + a = 0, – a is the inverse of a for addition.

Similarly, for a ≠ 0, a ×1/ a = 1 = 1/ a × a implies that 1/ a is the inverse of a

for multiplication.

Since – a ∉ N, – a can not be inverse of a for addition operation on N,

although – a satisfies a + (– a) = 0 = (– a) + a.

Similarly, for a ≠ 1 in N, 1/ a ∉ N, which implies that other than 1 no element of

N has inverse for multiplication operation on N.