Comprehensive Case Study NUR 7201

advertisement

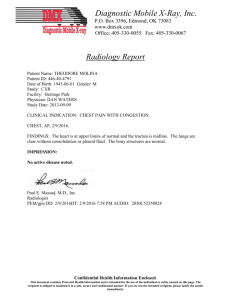

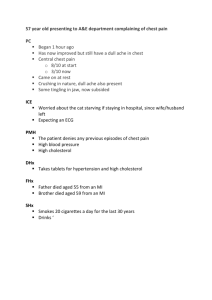

Running head: COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 Comprehensive Case Study NUR 7201 Ashley Peczkowski Wright State University NUR7201 1 COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 2 Comprehensive Case Study NUR 7201 Comprehensive Case Study Patient Information Name: G.M., Age: 79, Race: White, Gender: Male. Source and reliability Patient. He is reliable. Chief Complaint “After the procedure I started getting chest and arm pain and was having trouble getting my breath.” History of Present Illness Mr. G. is a 79 year old white male who presents with a gradual onset of sharp chest pain over 20 minutes that radiates to the right arm and back with increasing shortness of breath. He is a half hour post esophageal dilation for a history of achalasia. He has been tolerating a clear liquid diet post procedure. He states the pain began 20 minutes ago in the center of his chest. The pain has progressively become more intense and now radiates to his upper back and down his right arm. He describes the pain as a sharp pain that is worse with deep breathing and unable to be relived. During this time he has become increasingly more short of breath and had to be placed on two liters nasal cannula. He states the right side of his neck appears to have started to swell since the chest pain started. Past Medical History COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 3 Childhood illnesses. Whooping cough and chicken pox Immunization. Believes he received all his childhood vaccination. Influenza vaccination in September 2012. Pneumococcal vaccination three years ago. DPT vaccination three years ago. Adult illnesses. Achalasia (dx. 30 years ago), dysphagia (dx. 30 years ago), colon polyps (2008), benign essential hypertension (HTN) (2003), bronchitis (unknown), erectile dysfunction (2005), renal insufficiency (2010, hospitalized), Diabetes type 2 (2010, hospitalized), gastric esophageal reflux disease (unknown), glaucoma in the left eye (2011), and bilateral cataracts (2009). Operations. Esophageal dilations (multiple times over the past 30 years for achalasia. Most performed at VA hospitals), three esophageal Botox injections (2005, 2006, 2006. For achalasia), colonoscopy (2008. At VA hospital for polyp removal), and bilateral cataract removal (2011). Family History Mother- cancer, HTN, deceased; Father- unknown, deceased; Brother: asthma, HTN, MI, living. Social History Birthplace: Painesville, Ohio. Residence: Columbus, Ohio. Education: Middle school education. Work: Retired press machine worker. COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 4 Relationship: Married for 60 years. Sexual history: Yes, with wife only. Family: Wife only; No children. Tobacco use: Previous smoker of one pack a day for ten years. Quit 47 years ago. Alcohol: Denies. Drugs: No illicit drug use. Allergies No known allergies (NKA) Medications Omeprazole 40mg by mouth (PO) daily, and Lasix 20mg PO daily. Review of Systems General health. Overall good health. Denies recent weight changes Skin. Denies rash, lesions, pruritis, or changes in moles. New lower leg edema since admission. HEENT. Head. Denies headache, trauma, or vertigo. COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 5 Eyes. Denies recent visual changes, diplopia, or pain. Wears reading glasses post cataract removal surgery. Ears. History of hard of hearing has hearing aids. Denies tinnitus, discharge, or pain. Nose and sinuses. Denies discharge, obstruction, or epistaxis. Throat and mouth. Denies sores, lesions, bleeding, jaw pain, abnormal taste, hoarseness, or voice changes. Neck. Right neck swelling, Denies stiffness, adenopathy, or goiter Respiratory. Shortness of breath with rest, difficulty taking a deep breath. Denies orthopnea, wheezing, cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, pain, pleurisy, night sweats, TB exposure, pneumonia, or asthma. Does require two pillows to sleep at night. Cardiovascular. Sharp, mid-chest, chest pain that is constant but worse with breathing in and radiates to upper back and right arm, bilateral leg edema to knees. Denies palpitations, claudication, ascites, cold feet, phlebitis, or cyanosis. Gastrointestinal. Abdominal distention and left upper and lower abdominal quadrant pain. Denies nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight changes, hematemesis, melena, hemorrhoids, hernia, or rectal pain. COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 6 Genitourinary. Occasional incontinence. Denies oliguria, dysuria, hematuria, or nocturia. Musculoskeletal. Denies arthralgia, arthritis, myalgia, joint stiffness, swelling, or pain. Genital track. Current problems with erectile dysfunction, impotence, and changes in libido. Unaware of infertility issues. Denies penile discharge, lesions, sexual transmitted diseases, scrotal swelling, masses, testicular pain, or hernia. Neurological. Syncope in the past. Denies weakness, paralysis, seizures, incoordination, paresthesia, or impaired balance. Psychiatric. Denies depression, suicidal ideation, visual or auditory hallucinations, memory loss, or paranoia. Physical Exam Vital signs. Height: 5’7”, Weight: 189lbs., BMI: 29.6, Temp: 98.5 oral, HR: 95 SR, BP: 126/63, O2: 92% on 2LNC, RR: 18. General. COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 Older white male who appears stated age, moderately obese. Grimacing. Shallow respirations. Skin. Pink, warm, and dry. Bilateral lower extremity edema one plus pitting up to knees. HEENT. Head. Normocephalic, no masses or lesions Eyes. PERRLA. EOMI. No nystagmus or ptosis. Red reflex intact. Ears. TM’s non-injucted, good light reflex Nose and sinuous. Nares patent, no deformity, septal deviation or perforation. Nasal mucosa moist. Throat and mouth. Oral mucosa moist, gag presents, no lesions or sore, moderate dentation. Neck. No lymphadenopathy, masses, carotid pulses two plus bilaterally without bruits, supple, full ROM, trachea midline, right clavicle/ neck line swelling with crepitus, non-pitting. Respiratory. Bilateral basilar crackles with inspiration. No wheezing, rhonchi, or rub. Reparations even, shallow, and labored. No use of accessory muscles. Cardiovascular. 7 COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 SR on monitor, S1, S2, PMI at 6th ICS, 4cm lateral to MCL, no heaves or thrills, no mitral click hear, Pulses palpable in all 4 extremities, Pulses: Carotid: R-2+, L-2+, Brachial: R2+, L2+, Radial: R-2+, L-2+, Femoral: 2+, 2+, DP: R-1+., L-1+, PT: R-1+, L-1+. Gastrointestinal. Distended and firm with hyperactive bowel sounds in all four quadrants, no bruits, nontender to palpation, obese, liver, spleen, kidneys not palpable, no masses. Genitourinary. No lesions, inflammation or discharge from penis, rectal exam deferred, no external hemorrhoids or melena seen. Genital tract. Distribution and amount of hair constituent for age, no penile lesions or discharge, no evidence of inflammation or tenderness, epididymis without tenderness, inguinal canal without evidence of hernia. Musculoskeletal. Normal gait, no joint pain, stiffness or swelling, muscle strength 4/5 in all extremities. Neurological. CN II-XII intact, alert and oriented, cooperative, no focal defects. Extremities. 8 COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 9 Extremity size symmetric without swelling, mild atrophy, temperature warm bilaterally, all pulses presents two plus, skin pink-tan color with fair turgor and good capillary refill, without lesions; no femoral bruit, bilateral lower extremity one plus pitting edema, no clubbing of finer tips. Data. Abnormal labs. BUN 28, Cr-1.22, GFR-51, G-140, INR-1.4, PT-17.1, PTT-36, RBC3.59, Hgb-12.3, Hct-36.7, Lymps-20.4, mono-9.0 Chest x-ray. stable left chest tube, stable cutaneous staples, stable R tracheal deviation, Left pleural effusion persists, Left apical pneumothorax with pleural stripe measuring 2mm, left basilar atelectasis consolidation, stable ectasia, stable cardiac enlargement silhouette. . DVT prophylaxis. SCDs, ambulation twice, once with PT and once with RNs, heparin 5,000 units Q8 SQ. Antibiotics. Ertapanem, fluconazole, and Vancomycin prophylaxis for esophageal secretion into pleura. Differential Diagnosis The most likely differential diagnosis for this patient is pneumomediastinum secondary to an esophageal perforation. Other differentials could be acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, viral pleuritis, and costochondritis; in that sequence for degree of probability. Even though acute coronary syndrome and pulmonary embolism are not the most likely diagnosis, they must first be ruled out due to the high risk of morbidity and mortality. Acute coronary syndrome. COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 10 Acute coronary syndrome is associated with centralized chest pain that may radiate to the left arm, back, epigastric region, or jaw. Pain can be pressure, squeezing, or heaviness and is often associated with other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, and dizziness. Physical findings include jugular venous distention, S4 gallop, mitral regurgitation murmur, rales, tachycardia, hypotension, or bradycardia (Overbaugh, 2009). Acute coronary syndrome is not a likely diagnosis based on the patient’s history and because the ECG did not show signs of a STEMI or NSTEMI and the chest x-ray was positive for an apical pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum. Pulmonary embolism A pulmonary embolism is also not a likely diagnosis because the patient did not have hemoptysis, syncope, loud P2 sound, S4 gallop, jugular venous distention, or a right ventricular lift. More accurately the ECG would have shown tachycardia with S1, Q3, and T3 while the chest x-ray would have been normal or shown decreased perfusion. If clinical suspicion is high for a pulmonary embolism then a D-timer should be ordered (Agnelli & Becattini, 2010). Pneumonia and viral pleuritis. Pneumonia and viral pleuritis are also not as likely because the patient did not have leukocytosis. While the ECG will be normal, the chest x-ray will show infiltrates or effusion. Physical findings associated with pneumonia and viral pleuritis are decreased breath sounds, dull percussion, increased tactile fremitus, pleural friction rub, and fever. If clinical suspicion is high for pneumonia then blood cultures should be ordered and broad spectrum antibiotics are administered (King, Lee, Levy, Loscalzo, & Tucker, 2012). Costochondritis. COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 11 Costochondritis could be considered if the pain associated did not radiate to the right arm and the patient did not experience shortness of breath. Costochondritis usually precedes an acute injury and has a very specific reproducible pain. This is diagnosed through clinical exam and should be treated with NSAIDs (Proulx & Zryd, 2009). Pneumomediastinum. Pneumomediastinum is the most probable diagnosis based on history, physical and chest x-ray findings. Thirty minutes prior to the development of his chest paint he patient had just undergone an esophageal dilation for achalasia. Achalasia is an idiopathic disorder where the lower distal portion of the esophagus constricts and becomes aperistalsis while the lower esophageal sphincter experiences increased tone. This develops from a progressive neuronal degeneration of the myenteric plexus of Auerbach. The exact cause is unknown but it is thought to develop from an autoimmune response based on the reduced intramural ganglion cells secondary to inflammation. Achalasia is not curative and treatment is focused on symptom relief. Treatment includes Botox injections to the esophagus to relax the muscles, esophageal dilations to relieve the strictures, and a Heller myotomy procedure. A Heller myotomy is a long term treatment that involves cutting the esophageal muscles to prevent stricture (Ahmed, 2008). This inflammation pattern and the history of repeated dilations, reduces the amount of smooth muscle, leading to increased risk for perforation. Perforations tend to occur at the site of the stricture. Common signs of perforation are severe or persistent pain, dyspnea, tachycardia, subcutaneous crepitus over the chest and up into the neck area, and possibly a fever. The chest x-ray can be either normal or show signs of a perforation such as subcutaneous air, pneumothorax, or pneumomediastinum. A water soluble swallow esophagram is the gold standard of diagnosis and has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 92%. If the esophagram is negative and there is still COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 12 a high suspicion for perforation then a chest CT should be performed (Adler et al., 2006; Jonas et al., 2010). A barium swallow esophagram is not recommended because of the barium induce inflammation in the mediastinum if a perforation is present (Arne Soreide & Viste, 2011) Treatment for esophageal perforation includes operative, hybrid, and non-operative. Operative management involves anastomosis of the esophagus; hybrid management includes the use of endoscopy, video assisted thoracotomy, and sent placement; non-operative management is the practice of making the patient strict nothing by mouth and allowing the esophagus to heal on its own. Management and treatment within the first twenty four hours has been shown to reduce the risk of complications and length of stay (Carrott et al., 2011). Diagnostic Tests Acute chest pain differential work up. ECG. This patient developed a sudden onset of sharp chest pain that radiated to his back and right arm. An ECG was obtained to rule out acute events such as cardiac ischemia, pulmonary embolism, or abnormal cardiac findings such as dilated cardiomyopathy and mitral valve prolapse. In the presences of chest pain in individuals at risk for cardiac complications an ECG is the preferred test because of its rapid results. An ECG has the sensitivity of 76% and the specificity of 88% for acute myocardial ischemia (Baud et al., 2010). The results of the ECG were: normal sinus rhythm. CXR. COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 13 When performing an initial work up for acute chest pain, a chest x-ray is essential. This test is used to rule out other differentials such as pneumonia, viral pleuritis, pneumothorax, and cardiomegaly. The chest x-ray can show signs of an esophageal perforation such as pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum. It is recommended to obtain an upright chest x-ray for the evaluation of a pneumothorax because this position has a 37-58% sensitivity where as a supine position has a sensitivity below 30% (Albers, De Moya, Exadktylos, Haefeli, & Zimmermann, 2012). Results of current chest x-ray were: Right tracheal deviation with left apical pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum with pleural stripe measuring two millimeters. Right subcutaneous emphysema is seen in the neck and clavicle. Laboratory studies. The first initial test to obtain for acute chest pain is an ECG for signs of an MI. The second step is to obtain laboratory studies to help support or rule out differential diagnoses. Obtaining an initial CBC, BMP, troponin, CK, and BNP are ordered. The CBC is used for evaluation of hematology disease known to cause acute chest pain such as anemia and infections like pneumonia or viral pleuritis. The BMP is used to evaluate for electrolyte abnormalities known to cause cardiac arrhythmias which can cause chest pain. Elevated or decreased levels of potassium, calcium, and magnesium are prominent causes of cardiac abnormalities. Troponin and CK levels are used to evaluate if cardiac ischemia has been present causing chest pain. Lastly a BNP level is needed to evaluate fluid overload. Elevation in the BNP level is seen in conditions such as congestive heart failure and pulmonary edema; both of which are known to cause chest pain. Esophageal perforation work up. COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 14 Water soluble esophagram. A water soluble esophagram is the gold standard for evaluation of an esophageal perforation. Barium is not used where perforation is suspected because it is irritating to the tissues and can cause an inflammatory response and complications such as infection. When performing this exam the patient is instructed to drink a water soluble radiographic solution at which time a continuous x-ray is performed. This test allows the practitioner to visualize the patient ability to effectively swallow and the peristalsis response to the esophagus. It also allows visualization of the perforation by outlining the constrictions, tears, and escaping contrast into the pleural cavity. An esophagram may show a bird-break image at the site of the perforation and a dilated esophageal body. In some studies an esophagram was shown to have a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of about 89%. The best time to perform this test is within the first 24 hours; after this time the leak is often difficult to locate and a chest CT is preferred (Boeckxstaens & Richter, 2011; Jonas et al., 2010; Stewart, 2005) Chest and abdomen CT. A commuted tomography (CT) can be performed for the evaluation of an esophageal perforation if the esophagram is negative and there is still a high suspicion. Oesophagus perforation appears as a pneumomediastinum, peri-oesophagel air, or abnormal mediastinum contour as the result of fluid, hematoma, or mediastinitis. Most times a pneumomediastinum is found. This develops from the Macklin effect which is air dissecting along the bronchial and spreading into the interstitial emphysema into the mediastinum. A pneumomediastinum can be mistaken for a pneumothorax or they can co-exist together. A Pneumomediastinum can be differentiated from a pneumothorax by the septae within the pneumomediastinum (Oikonomou COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 15 & Prassopoulos, 2011). A CT has a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 85% for the evaluation pneumomediastinum (Bergen, Dissanaike, & Jurkovich, 2011). Endoscopy. The use of a flexible endoscopy has gained support over the years but is still controversial. The use of endoscopy for esophageal perforation diagnosis varies depending on the institution. Some institutions prefer an endoscopy because of the high sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 92%. The added benefit is the placement of endoscopic stenting during the procedure for conservative management (Jonas et al., 2010). Plan The treatment for esophageal perforation varies from patients depending on the severity, age, complications, and risk factors. A more conservative approach is recommended for small perforations without systemic involvement. Surgery is preferred for large leaks and for those with systemic complications or diseases affecting the esophagus or lungs. Systemic involvement includes sepsis, mediatinitis, and multi-organ failure; diseases affecting the esophagus include extended perforation and esophageal cancer, while diseases affecting the lung are pleural effusions and emphysema (Jonas et al., 2010). For this patient surgery was indicated because of his advanced age and systemic involvement. The chest x-ray showed the development of a pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and extensive subcutaneous emphysema indicating a more severe perforation. Plan is to perform an esophagram which showed an extensive perforation and leak into the pleural cavity. Because the patient had been eating and drinking after the perforation, a lung decortication and washout is needed to remove the developing empyema (Murthy, 2013). Once the lung has debrided of infection a double chest tube is placed for COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 16 removal of further infection development and pneumothorax. The pneumomediastinum is generally left alone and allowed to be reabsorbed by the body. If severe enough another chest tube can be placed across the mediastinum (Fleischer, Fujii, Harrison, & Lau, 2010) The perforation is anastomosed by simple dissolvable sutures. A nasogastric tube is placed to remove gastric secretions to prevent to build up which can cause distention and pressure on the new anastomosis. Distention and pressure placed on the anastomosis can cause the site to re-rupture. An esophageal stent placed through endoscopy is recommended because the thinned esophagus from the achalasia and repeated dilation. The placement of a stent helps prevent anastomotic leaks, reducing the mortality rate, complication rate, and overall length of stay (Gullichsen, Laine, & Salminen, 2009). Because the patient experienced a perforation from his dilation, he can no longer receive esophageal dilations. This requires the patient to have a laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) to prevent esophageal stricture from achalasia in the future. A LHM and Dor’s antireflux procedure are now being considered the procedure of choice for permanent treatment. This is performed by dividing the phrenoesophageal ligament and mobilizing the lateral and anterior side. A myotomy is performed six centimeters above the gastroesophageal junction and one to 1.5 centimeters above the stomach. Lastly an anterior 180degree fundoplication is performed according to the Dor method. Symptoms of esophageal stricture such as dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain, and weight loss after the surgery are measured to evaluate effectiveness. This is called the Eckardt score and a score of three or higher indicates treatment failure (Table 1.) (Annese et al., 2011). Finally, a gastrostomy (G-tube) and jejunostomy (J-tube) tube are placed. The G-tube is placed to straight drain for gastric decompression and the J-tube for enteral feeding with tube feeds. The NG is kept in place for 4872 hours to ensure the G-tube is effective at gastric decompression through the removal of COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 17 chyme. After this time the NG can be removed. The bowel is kept at rest until bowel functions return post-surgery. Once bowel function has returned and the patient has experienced flatulence then tube feedings can’t be initiated. Dietary is consulted for recommending tube feeding formula. Tube feeding at started at 20cc/hr and increased after 24 hours by 10cc/hr every eight hours. Residuals should be checked every four hours (Berger, 2013). Strict NPO status is required to allow for proper healing for a two week period, at which time another esophagram is performed. If the patient passes the exam without signs of a leak then he will be placed on a clear liquid diet. The diet can be progressed slowly to a regular soft diet if the patient does not experience difficulty swallowing, pain, or show signs of infection. Once the diet is resumed, tube feeds can be stopped. Management of the patient post-surgery is complex and detailed oriented. Broad spectrum antibiotics are indicated for the treatment empyema. Because the perforation occurred in the hospital setting, therapy to treat common hospital acquired infections are also indicated. This patient will be placed on ertapanem one gram intravenously (IV) once daily, fluconazole 200mg IV once daily, and Vancomycin 1,750mg IV once daily. This allows for the most optimal coverage for hospital acquired infection, fungal coverage, gram negative coverage, and gram positive coverage. Vancomycin trough should be obtained before the third dose and then weekly (Jonas et al., 2010). Strict NPO status is important to prevent infections and allow for bowel rest, healing, and reduced gastric secretions. Even though the patient is not intubated, daily mouth care is needed to prevent the buildup of bacteria as the patient can still obtain aspirate pneumonia. Other medications should be heparin 5,000 units SQ every eight hours for deep venous thrombosis prevention; Omeprazole 40mg IV daily for stress ulcer prevention; Hydromorphone 0.5mg IV every two hours and oxycodone liquid five to ten milligrams per j- COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 18 tube every three hours as needed for pain; And metroprolol 2.5mg every six hours as needed for systolic blood pressure over 160 or diastolic blood pressure over 90. Dressing should be changed daily for three days or until drainage stops. Once the incision sites are healed and no longer draining, then the incision should be left open to air. The chest tube dressing should be changed daily after 48 hours with a clean, dry drainage sponge. Clean drainage sponges should also be placed around the G and J-tube for drainage and comfort (Ayello, Nicks, Nitzki-George, Sibbald, & Woo, 2010). Aggressive pulmonary prevention is needed to reduce atelectasis and pneumonia. This is achieved through the use of an incentive spirometer ever hour, coughing and deep breathing every two hours, and ambulation in the hallway at least three times a day. Because this patient is older, physical and occupation therapy should be consulted for aggressive management and evaluation of physical strength. Electrolytes are monitored closely and replaced as needed. Potassium and magnesium are kept above four and two mmol/L to prevent the development of atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation is a common complication of thoracic surgery because of the fluid shifts experienced (D’Amico, Harpole, O-Brien, Onaitis, & Zhao, 2010) Follow Up Discharge follow up for esophageal perforation requires frequent clinic visits and tests; this is because perforations carry a high risk of complications and mortality. The patient will be schedule for an office visit in two weeks and with a chest x-ray prior to arrival. This allows the practitioner to view the x-ray with the patient in the office. The chest x-ray is obtained for evaluation of the lungs. Many patients are discharge with a small apical pneumothorax which can take weeks to fully be reabsorbed by the body. Other aspects are also evaluated such as fluid overload, atelectasis, and capsulated pleural infections (Stewart, 2005). During the first follow up appointment a thorough assessment is completed along with review of home medications, diet, COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 19 and activity. It is important to assess the patients breathing status and current diet. Monitor respiration rate, listen to breath sounds, and percuss for fluid or air. This focused assessment allows the practitioner to evaluate for pneumothorax, pleural effusions, pulmonary congestion, and other post-surgery complications. Diet is also very important to evaluate at this encounter. The patient should still remain on a soft diet post discharge for three months. Long term diet restrictions include avoidance of irritating and spicy foods, alcohol, hard foods, and encouragement of small bits. If the patient experiences weight loss or malnutrition then a nutritional consult should be order. Ask the patient if he is still taking his omeprazole and prescribe a new prescription for long term reflux management. Next assessment of wound healing and removal of staples are performed. Prescribe dressing changes as needed based on wound evaluation. At the two week follow up most patients are well healed and do not need to perform wound dressing changes. An Eckardt score should be obtained at each follow up appointment for effectiveness of the Heller myotomy (Annese et al., 2011). If the patient reports difficulty swallowing or pain then a follow up esophagram should be scheduled. A cross sectional cohort study between 1994 and 2002 was followed-up with a mean of 3.1 years. This study took 179 patients, 106 which had been treated with dilation and 73 of which had the LHM. Average age was about 49 years and 52% were male. All patients had achalasia with a history of dysphagia. Of the 70% who followed up successful treatment with LHM was 89% at six months and 57% at six years. Success was defined as dysphagia or regurgitation less than three times a week (Baker et al., 2006). An ECG is not needed if the patient did not develop atrial fibrillation because atrial fibrillation development peaks between the third and fifth day after surgery. If the patient did develop atrial fibrillation an ECG would need to be obtained two months after discharge. At this time the metroprolol is typically discontinued as the atrial fibrillation usually is COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 20 resolved by this time. If the ECG continues to show atrial fibrillation then the patient is referred to a cardiologist for long term management (D’Amico et al., 2010). Continued follow up in two months, six months, and one year should be scheduled. Table 1. Score Symptoms Weight Loss (kg) Dysphagia Retrosternal Pain Regurgitation 0 None None None None 1 <5 Occasional Occasional Occasional 2 5-10 Daily Daily Daily 3 >10 Each Meal Each Meal Each Meal Modified from: Annese et al., 2011 Health Promotion Health promotion is an important part of in-hospital treatment and follow care. Health promotion consists of prevention screening, vaccinations, BEERs criteria, exercise programs, nutritional management, and many others. Specific health promotion for this patient would consist of vaccination screening, BEERs criteria evaluation of medications, nutritional evaluation, and exercise promotion. This patient should be up to date with current vaccination especially influenza and pneumococcal vaccination. If the patient has not had theses vaccination then they should be administered in the hospital before discharge. This prevents development of the flu and pneumonia which can become a life threatening condition for elderly and postoperative patients (Appel et al., 2010). Next the patient’s medications should be fully examined along with side effect profile. This has been completed through the development of the BEERs criteria in which medications are suggested and discouraged based on their side effects and COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 21 accumulation in the elderly. The BEERs criteria are to be used as a guideline only so the patient may be on medication not approved by the BEERs criteria if the benefit versus risk ratio is high. This evaluation reduces the risk of drug related complications that could potentially harm the patient. This includes orthostatic hypotension, delirium, syncope, constipation, urinary retention, and many others. If the hospital provides a geriatric practitioner then gerontology should be consulted for their expert opinion (Chrischilles, Kaboli, Lund, & Steinman, 2011). Finally the importance of nutritional and exercise evaluation is essential to promote discharge home, maintain physical safety, and reduce post-operative complications. Because this patient had surgery on his esophagus his ability to swallow foods and maintain caloric intake should be evaluated. Correct nutrition helps the patient maintain a healthy weight, improve healing, provide strength, and improve immune response. If the patient suffers from difficulty swallowing he should be referred to a speech pathologist for recommendations and therapy. A nutritionist should be consulted for dietary recommendations of soft foods which are healthy and can maintain enough caloric intake. If this is not achievable then at home tube feedings my need to be initiated. The patient should monitor blood glucose levels closely to prevent hypoglycemia. The patient should be encouraged to exercise daily to improve strength, reduce weight, and stimulate a healthy immune system. Prescribing an exercise program has shown to increase adherence to recommendations. Health promotions should be discussed in detail daily in the hospital and at each follow up appointment (Appel et al., 2010). COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 22 References Adler, D., Baron, T., Davila, R., Egan, J., Faigel, D., Fanelli, R., ... Zuckerman, M. (2006). Standards of practice committee. Esophageal dilation. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 63(6), 755-760. Retrieved from http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=9304 Agnelli, G., & Becattini, C. (2010). Acute pulmonary embolism. The New England Journal of Medicine, 363, 266-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1059/NEJMra0907731 Ahmed, A. (2008). Achalasia: What is the best treatment? Annals of African Medicine, 7(3), 141148. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.55662 Albers, C., De Moya, M., Exadktylos, A., Haefeli, P., & Zimmermann, H. (2012). Can handheld micropower impulse radar technology be used to detect pneumothorax? Initial experience in a European trauma center. Injury, 44(5), 650-654. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2012.02.001 Allen, J., Belafsky, P., Leonard, R., & White, C. (2012). Comparison of esophageal screen findings on videofluoroscopy with full esophagram results. Head & Neck, 34(2), 264269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hed.21727 Annese, V., Boeckxstaens, G., Bruley des Varannes, S., Busch, O., Chaussade, S., Costantini, M., ... Zwinderman, A. (2011). Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 364(), 1807-1816. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1010502 Appel, L., Arnett, D., Daniels, S., Fonarow, G., Greenlund, K., Ho, M., ... Yancy, C. (2010). Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction. Circulation, 121, 586-613. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 23 Arne Soreide, J., & Viste, A. (2011). Esophageal perforation: Diagnostic work-up and clinical decision-making in the first 24 hours. Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation, and Emergency Medicine, 19(66), 1-7. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/17577241-19-66.pdf Ayello, E., Nicks, B., Nitzki-George, D., Sibbald, G., & Woo, K. (2010). Acute wound management: Revisiting the approach to assessment, irrigation, and closure considerations. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 3(4), 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12245-010-0217-5 Baker, M., Blackstone, E., Khandwala, F., Rice, T., Richter, J., Vela, M., & Wachsberger, D. (2006). The long term efficacy of pneumatic dilation and Heller myotomy for the treatment of achalasia. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 4(5), 580-587. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1542-3565(05)00986-9 Baud, F., Deye, N., Dillinger, J., Henry, P., Logeart, D., Sideris, G., & Voicu, S. (2010). 335 sensitvity and specificity of post-resuscitation ECG for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Emergencies and Intensive Care in Cardiology, 2(1), 111-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S187-6480(10)70337-2 Ben-David, K., Carreras, J., Chauhan, S., Collins, D., Draganov, P., Forsmark, C., ... Wagh, M. (2010). Minimally invasive treatment of esophageal perforation using a multidisciplinary treatment algorithm: A case series. Endoscopy, 43, 160-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s0030-1256094 Bergen, V., Dissanaike, S., & Jurkovich, G. (2011). Pneumomediastinum in blunt trauma: A review. Trauma , 13(3), 199-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1460408611405267 COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 24 Berger, W. (2013). Tube feeding: Indications, considerations, and technique . In P. Belafsky, C. Easterling, G. Postma, & R. Shaker (Eds.), Principles of Deglutiition (pp. 965-986). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3794-9_68 Boeckxstaens, G., & Richter, J. (2011). Management of achalasia: Surgery or pneumatic dilation. Gut, 869-879. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.212423 Bohrn, M., Browne, B., & Mattu, A. (2011). Chest pain. In Cardiovascular Problems in Emergency Medicine: A Discussion-based Review (pp. 3-70). West Sussex, United Kingdom : Jon Wiley & Sons Ltd. . Carrott, P., Felisky, C., Hubka, M., Kline, E., Koehler, R., Kuppusamy, M., & Low, D. (2011). Evolving management strategies in esophageal perforation: Surgeons using non operative techniques to improve outcomes. The American College of Surgeons, 213(1), 164-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.059 Choure, G., & Goldman, J. (2010). Metabolic disturbances of acid-base and electrolytes. In Critical Care Study Guide (pp. 691-713). New York: Springer. Chrischilles, E., Kaboli, P., Lund, B., & Steinman, M. (2011). Beers criteria as a proxy for inappropriate prescribing of other medications among older adults. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 45(11), 1363-1370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1345/aph.1Q361 D’Amico, T., Harpole, D., O-Brien, S., Onaitis, M., & Zhao, Y. (2010). Risk factors of atrial fibrillation after lung cancer surgery: Analysis of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 90(2), 368-374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.100 Fleischer, D., Fujii, L., Harrison, M., & Lau, A. (2010). Successful nonsurgical treatment of pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum, and COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 25 subcutaneous emphysema following ERCP. Gastoenterology Research and Practice, 1-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2010/289135 Gullichsen, R., Laine, S., & Salminen, P. (2009). Use of self-expandable metal stent for the treatment of esophageal perforations and anastomotic leaks. Surgical Endoscopy , 23(7), 1526-1530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0432-4 Jonas, S., Neuhaus, P., Pratschke, J., Rosch, T., Schmidt, S., Schumacher, G., ... Weidemann, H. (2010). Management of esophageal perforations . Surgery Endoscopy , 24, 2809-2813. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1054-6 King, L., Lee, L., Levy, B., Loscalzo, J., &Tucker, K. (2012). A complex cause of pleuritic chest pain. The New England Journal of Medicine, 367, 1742-1748. http://dx.doi.org/10.1059/NEJMcps1208614 Murthy, S. (2013). Lung decortication . In B. Mandell (Ed.), Perioperative Management of Patients with Rheumatic Disease (pp. 385-388). New York: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2203-7_38 Oikonomou, A., & Prassopoulos, P. (2011). CT imaging of blunt chest trauma . European Society of Radiology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13244-011-0072-9 Overbaugh, K. (2009). Acute coronary syndrome. The American Journal of Nursing, 109(5), 4252. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Abstract/2009/05000/Acute_Coronary_Syndrome.28.a spx Proulx, A., & Zryd, T. (2009). Costochondritis: Diagnosis and treatment . American Family Physician, 80(6), 617-620. Retrieved from http://www.aafp.org/afp/2009/0915/p617.html COMPREHENSIVE CASE STUDY NUR 7201 Stewart, M. (2005). Pharyngeal trauma. In Head, Face, and Neck Trauma: Comprehensive Management (pp. 223-238). New York: Thieme. 26