Viewpoints on Japanese American Internment

advertisement

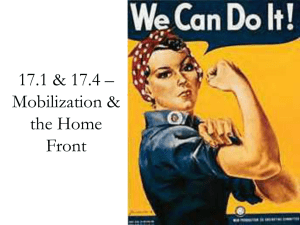

Viewpoints on Japanese American Internment In early 1942, the Secretary of War ordered the evacuation of Japanese Americans from Arizona, California, Oregon, and Washington. Many Americans defended the internment of Japanese Americans on the grounds that constitutional rights during wartime may be suspended because of necessity. Others who opposed the internment policy argued that constitutional rights must always be protected, even in wartime. Argument 1; Walter Lippman, American columnist, February 12, 1942 It is the fact that the Japanese navy has been reconnoitering the Pacific Coast more or less continually and for a considerable period of time, testing and feeling out American defenses. It is the fact that communication takes place between the enemy at sea and enemy agents on land. These are facts which we shall ignore at our own peril. I understand fully and appreciate thoroughly the unwillingness of Washington to adopt a policy of mass evacuation and mass internment of all those who are technically enemy aliens. But I submit that Washington is not defining the problem on the Pacific coast correctly and that it is failing to deal with the practical issues promptly. The Pacific coast is officially a combat zone: some part of it may at any moment be a battlefield. Nobody’s constitutional rights include the right to reside and do business on a battlefield. Argument 2; Supreme Court decision 1943 In 1942, Gordon K. Hirabayashi, a senior at the University of Washington, refused to register for deportation and deliberately violated an 8:00 pm curfew imposed on Japanese Americans living in Seattle. He was tried and convicted of both offenses, and the Supreme Court upheld his conviction. The war power of the national government is “the power to wage war successfully.” It extends to every matter and activity so related to war as substantially to affect its conduct and progress. The power is not restricted to the winning of victories in the field and the repulse of enemy forces. It embraces every phase of the national defense, including the protection of war materials and the members of the armed forces from injury and from the dangers which attend the rise, prosecution, and progress of war. . . Like every military control of the population of a dangerous zone in wartime, it necessarily involves some infringement of individual liberty, just as does the police establishment of fire lines during a fire, or the confinement of people to their houses during an air raid alarm—neither of which could be thought to be an infringement of constitutional right. . . Distinctions between citizens solely because of their ancestry are by their very nature odious to a free people whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equality. For that reason, legislative classification or discrimination based on race alone has often been held to be a denial of equal protection. . . we may assume that these considerations would be controlling here were it not for the fact that the danger of espionage and sabotage, in time of war and of threatened invasion, calls upon the military authorities to scrutinize every relevant fact bearing on the loyalty of populations in dangerous areas. Because racial discriminations are in most circumstances irrelevant and therefore prohibited, it by no means follows that, in dealing with the perils of war, Congress and the Executive are wholly precluded from taking into account those facts and circumstances which are relevant to measures for our national defense and for the successful prosecution of the war, and which may in fact place citizens of one ancestry in a different category from others. . . .The adoption by Government, in the crisis of war and of threatened invasion, of measures for the public safety, based upon the recognition of facts and circumstances, which indicate that a group of one national extraction may menace that safety more than others, is not wholly beyond the limits of the Constitution and is not to be condemned merely because in other and in most circumstances racial distinctions are irrelevant. . . Argument 3: Supreme Court dissenting opinions in Korematsu v. United States, 1944 In 1943, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the internment policy, and in the 1944 case Korematsu v. United States, it reaffirmed its earlier decision. Mr. Justice Frank Murphy, dissenting: Justification for the exclusion is sought, instead, mainly upon questionable racial and sociological grounds not ordinarily within the realm of expert military judgment, supplemented by certain semi-military conclusions drawn from an unwarranted use of circumstantial evidence. Individuals of Japanese ancestry are condemned because they are said to be “a large, unassimilated, tightly knot racial group, bound to an enemy nation by strong ties of race, culture, custom, and religion.”. . . It is intimated that many of these individuals deliberately resided “adjacent to strategic points,” thus enabling them “to carry into execution a tremendous program of sabotage on a mass scale should any considerable number of them have been inclined to do so.”. . . The main reasons relied upon by those responsible for the forced evacuation, therefore, do not prove a reasonable relation between the group characteristics of Japanese Americans and the dangers of invasion, sabotage, and espionage. The reasons appear, instead, to be largely an accumulation of much of the misinformation, half-truths, and insinuations that for years have been directed against Japanese Americans by people with racial and economic prejudices—the same people who have been amongst the foremost advocates of the evacuation. . . . I dissent therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life. It is unattractive in any setting but it is utterly revolting among a free people who have embraced the principles set forth in the Constitution of the United States. All residents of this nation are kin in some way by blood or culture to a foreign land. Yet they are primarily and necessarily a part of the new and distinct civilization of the United States. They must accordingly be treated at all times as the heirs of the American experiment and as entitled to all the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. Mr. Justice Robert Jackson, dissenting: I should hold that a civil court cannot be made to enforce an order which violates constitutional limitations even if it is a reasonable exercise of military authority. The courts can exercise only the judicial power, can apply only law, and must abide by the Constitution, or they cease to be civil courts and become instruments of military policy. Questions to think about: 1. What arguments did Lippmann and certain justices of the Supreme Court use to justify internment policy? 2. Why did Justices Murphy and Jackson oppose the internment policy? Assignment: Write a one page, typed, double-spaced essay where you react to the following question: Under what circumstances, if any, should the U.S. government be permitted to curtail [restrict] the civil rights of its citizens? Use specific quotes and/or historical examples to support your position. See rubric below. 1 2 3 4 Thesis did not give a clear opinion on whether government should be able to limit civil rights, nor did it preview what will be discussed. Included 1 piece of relevant evidence (fact, statistic, historical example, quote) that shows understanding of civil rights. Many grammatical or spelling errors that distract from the content. Author’s opinion on government limiting rights was not clear in the thesis. Included at least two pieces of relevant evidence (fact, statistic, historical example, quote) that support the topic but did not explain or credit sources. Several grammatical or spelling errors. Author’s opinion on government’s ability to limit civil rights was clear in the thesis. Included 2 pieces of relevant evidence (fact, statistic, historical example, quote) that support the thesis that are explained. Identified sources as needed. A few grammatical or spelling errors that do not distract from content. Author’s opinion on government’s ability to limit civil rights was clear in the thesis and the main points were outlined in the introduction. Included 3 or more relevant pieces of evidence (fact, statistic, historical example, quote) that support the thesis that are explained. Identified sources as needed. No grammatical or spelling errors.