File

advertisement

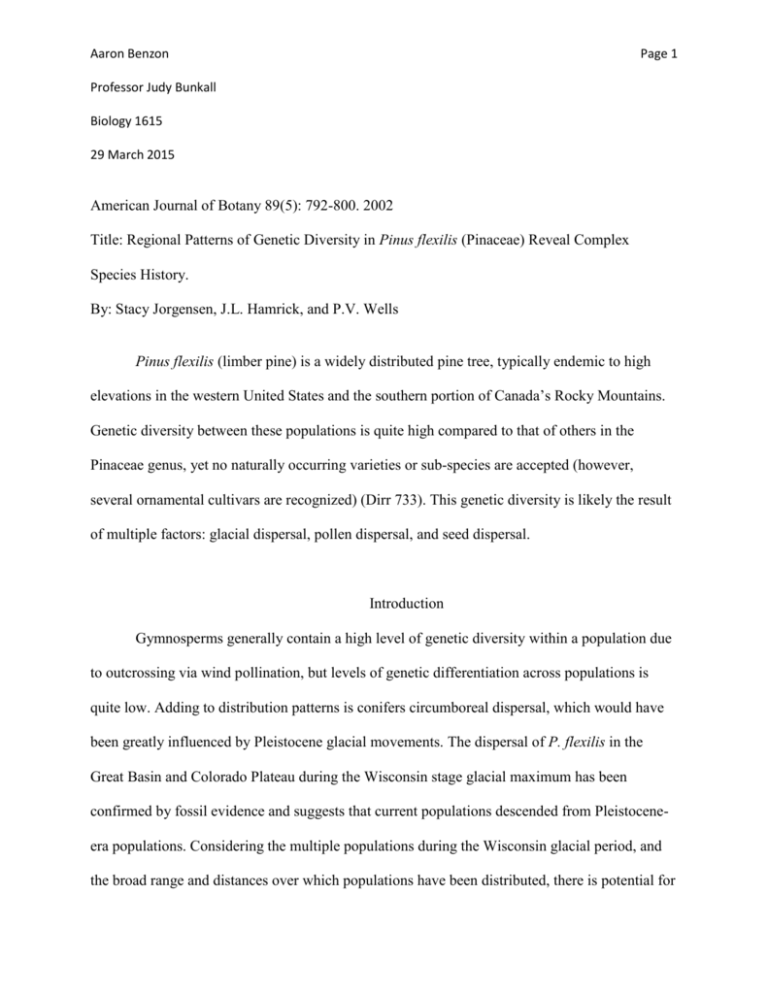

Aaron Benzon Page 1 Professor Judy Bunkall Biology 1615 29 March 2015 American Journal of Botany 89(5): 792-800. 2002 Title: Regional Patterns of Genetic Diversity in Pinus flexilis (Pinaceae) Reveal Complex Species History. By: Stacy Jorgensen, J.L. Hamrick, and P.V. Wells Pinus flexilis (limber pine) is a widely distributed pine tree, typically endemic to high elevations in the western United States and the southern portion of Canada’s Rocky Mountains. Genetic diversity between these populations is quite high compared to that of others in the Pinaceae genus, yet no naturally occurring varieties or sub-species are accepted (however, several ornamental cultivars are recognized) (Dirr 733). This genetic diversity is likely the result of multiple factors: glacial dispersal, pollen dispersal, and seed dispersal. Introduction Gymnosperms generally contain a high level of genetic diversity within a population due to outcrossing via wind pollination, but levels of genetic differentiation across populations is quite low. Adding to distribution patterns is conifers circumboreal dispersal, which would have been greatly influenced by Pleistocene glacial movements. The dispersal of P. flexilis in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau during the Wisconsin stage glacial maximum has been confirmed by fossil evidence and suggests that current populations descended from Pleistoceneera populations. Considering the multiple populations during the Wisconsin glacial period, and the broad range and distances over which populations have been distributed, there is potential for Page 2 broad genetic diversity over its territories. These distribution patterns will also most likely reflect size and location of Wisconsin stage populations. Another factor for consideration in P. flexilis genetic diversity is distribution of seed by birds. Other than wind pollination, Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga Columbiana) is currently the sole regenerative mechanism for the species. Distances of seed dispersal can vary from a few hundred meters to an observed 22 km. Study objectives were to (1) determine quantities of genetic diversity and distribution within populations, (2) determine geographic dispersal and genetic variations among populations, especially due to glacial advances, and (3) consider and compare genetics of other western North American pine species to those of P. flexilis. Material and Methods Field Sampling- Thirty populations of P. flexilis were sampled from core ranges. Tissue samples from branches and buds were randomly selected from individuals. These samples were stored in plastic bags at 5ºC until enzyme extraction. Laboratory Analysis- Tissue was frozen using liquid nitrogen and then crushed with a mortar and pestle. Enzymes were collected from powered samples. Gel electrophoresis was conducted resulting in 12 enzyme systems. Page 3 Statistical Analysis- Four geographic regions were defined in order to assess broad geographic trends: Utah Rocky Mountains, Northern Rocky Mountains, Colorado Rocky Mountains, and Basin/Range. The subscript “s” was used to indicate species, subscript “p” to indicate population, and “f” as a statistic for polymorphic loci. Genetic analysis were gathered by three methods. (1) Measures of heterozygosity at the polymorphic locus and average genetic diversity within and among populations. (2) Identification of location of polymorphic alleles. (3) Genetic distances from population to population were calculated. Results Genetic Diversity- A wide range of genetic diversity was found within populations with 20 of 21 allele loci being polymorphic. Among populations P. flexilis showed a 10% genetic diversity and a small, but significant, genetic to geographic relationship was found. A significant similarity was also found in the Northern and Utah Rocky Mountain populations which happen to follow a predominantly north to south orientation. Regional Variations- While little variation manifested in terms of alleles at polymorphic loci, there were strong differences between the Basin/Range populations and the Northern Rocky Mountain populations due to heterozygosity. A factor found inbreeding highest in the Basin/Range and Utah Rocky Mountain populations. Page 4 Discussion While P. flexilis has a higher mean genetic diversity than pines as a whole, it is average for other widespread pines in Western North America. Typically plant species over such dislocated mountain terrain show less genetic diversity within their populations, but higher genetic diversity among populations. The opposite was concluded for P. flexilis. Distribution of P.flexilis by Pleistocene glacial movement was most significant in the northern Rocky Mountain ranges. Conversely, the Basin/Range populations would have existed at lower, ice-free elevations during the Pleistocene Era and Wisconsin glaciations meaning the Basin/Range populations were not transported as the northern Rocky Mountain populations, but rather have long existed in their same ranges. These findings indicate two strong genetic divisions for P. flexilis. That dividing factor is in fact the continental divide. Populations to the east of the continental divide appear to be descended from Wisconsin stage Great Plains populations, while populations found to the west of the continental divide are descendants of the Basin/Range populations. In conclusion, the findings indicate three primary factors that have influenced genetic variation. (1) Glacial distribution of Pleistocene populations, (2) avian seed dispersal following glacial retreats, and (3) more recent genetic dispersal via pollen and seed. Works Cited Dirr, Michael. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants: Their Identification, Ornamental Characteristics, Culture, Propagation and Uses. Champaign, IL: Stipes Pub., 1998. Print. Page 5