Andrea Tarnowski, Dartmouth College Philippe de Mézières` Epistre

advertisement

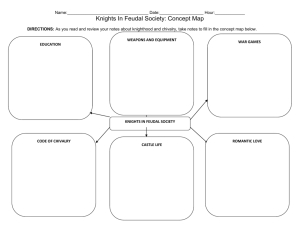

Philippe de Mézières' Epistre lamentable et consolatoire, Written after the defeat of French/Western forces in Bulgaria in 1396, Mézières' thought and style in the Epistre lamentable et consolatoire are marked by a spirit of equation in the service of transcendence. He lines up and connects contemporary figures, historical examples, and a variety of metaphors and allegory in a vast network of similitude, and then uses these equated terms and images to promote the single objective of forming a new chivalric order. For example, he draws analogies between himself, his dedicatee the Duke of Burgundy, King Charles VI of France, and Christians generally. He envisions the knighthood he wants to found as a medecine, a city, an altar, and an ark. He requires perfect unity of purpose among the crusaders he seeks to recruit; the three geographical branches he foresees will act in concert, simultaneously single and triple in echo of the Holy Trinity. The knights will all dress the same, obey a single code, live from the same purse, hold the same ideal. Mézières's self-positioning as an author is of prime importance. In the Epistre lamentable, Mézières has a delicate task in conjoining an account of an on-the-ground event with the projection of a transcendent aim. He must deplore the defeat at Nicopolis, posit that Christians lost because of sinful overconfidence, and propose that his order can, in "less that a hundred weeks," as he says, position Western forces for success. He has a notable advantage in speaking as an authority on peoples of the East; he evokes the years he spent as chancellor of Cyprus and carefully provides his reader with a history of Ottoman conquest. His remarks about the false character of those who follow Mohammed are unsurprising; more striking is the fact that he describes Turks as possessing the flawless discipline that Christian troops require. A second example of admiration for the miscreant is his depiction of the living habits of the "Grand Khan de Tartarie" (whose doings have been described to him by an eyewitness friend). The Khan sets up living quarters surrounded by a million troops and horses, arrayed in irreproachable order; when the resources of the site become scarce, he packs up, moves on, and sets everything up just as meticulously the next time. For Mézières and the Epistre lamentable, this description has import beyond face value; it does not simply acknowledge a talent for establishing and breaking military camp. Mézières praises what he calls the Khan's "cité portative," or portable city; this is precisely the term he evokes repeatedly to define the chivalric order that will avenge the deaths of Nicopolis and go on to retake Jerusalem. His knights must form a portable city, carrying Christ in their hearts and divesting themselves of material ties. The image of the Khan's camp allows Mézières both to target Christian error at Nicopolis - overly concerned for their own comfort, the knights were arrogant and careless in the conviction they would win -- and provide a material template for spiritual reform. Mézière's idea of a portable city of Christian devotion thus finds a platform outside France and Europe.