Core Principles of Engaged Teaching and Curricula UVU Faculty

advertisement

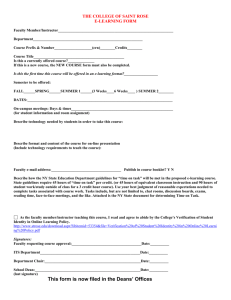

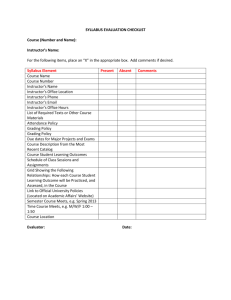

Updated February, 2011 p.1 Core Principles of Engaged Teaching and Curricula UVU Faculty Center for Teaching Excellence PURPOSE This document proposes a definitional model for “excellent” teaching at UVU based on the scientific literature regarding adult learners. This document is intended to assist in the following ways: 1) Assessment of a candidate's teaching abilities during a hiring evaluation 2) Faculty self-assessment for improving their own teaching practices and approach 3) RTP annual (with Department chair), mid-term, tenure, and post-tenure reviews and decisions regarding a candidate's teaching performance; alternatively, a model for suggesting improvement for a faculty member who is struggling to improve their teaching 4) Reviews and discussions of rehiring of adjunct faculty and lecturers 5) A model for peer reviews of a faculty member's teaching performance for RTP reviews, feedback, or mentoring 6) A set of organizing criteria for evaluating Teaching Excellence Awards. These core principles represent the emerging consensus regarding the best teaching practices that actively promote student learning and engagement. Agreement on a single, unitary definition of excellence in teaching may not be possible since teaching methods will vary by discipline and need to be customized. However, UVU could agree on a set of core principles regarding excellence in engaged teaching. Having a definition of core principles might also encourage development of practical measures of departmental and institutional assessment. Such measures could provide effective feedback to faculty, department chairs, and deans with regard to how well we are doing in fulfilling UVU’s mission of fostering student success and preparing competent professionals who are engaged lifelong learners that contribute to their communities. We encourage this definition of engaged teaching to be discussed among deans, department chairs, RTP chairs, and faculty. There are faculty who are already making use of some of these methods and who actively engage students in their classrooms and in the community. We hope they will find this document supportive of their engaged teaching strategies and useful in finding new ways to think about their teaching to improve it or expand it even further. CORE PRINCIPLES The overarching principle of engaged teaching is that the instructor is concerned foremost with student learning and what students are doing in the classroom and the community rather than being focused on what he or she is doing and saying. This requires a shift away from traditional methods of instruction and increased concern with "behind the scenes" course design and course objectives. Consequently, this also requires a shift in how faculty are evaluated with regards to their teaching. Creation of a classroom environment conducive to learning (e.g. instructor concern for students, active student participation, student cohesiveness, class is organized, sufficient learning resources are available to students, emotional safety is present, etc.) To increase student motivation and engagement, the instructor shares decision-making with students; students make real decisions that affect their grades and their learning. These decisions can include, but are not limited to, any of the following: assignments, course schedule, content to be covered, due dates, course policies, contract grading, mastery grading, etc. Students are actively encouraged to learn material that is not discussed in class but that will be assessed in addition to material that will help them in the future after the course is over. This principle must be evaluated in the context of the level of the course and external constraints. Undergraduate mentored research should also involve shared decision-making. Updated February, 2011 p.2 The instructor appropriately increases course focus on skill/competencies development, realigns course objectives to match this focus, and makes use of course content to ensure students learn key thinking skills as well as developing a knowledge base in the discipline. Engaged instructors are not wedded to "covering the content", but use of key concepts from course content as the basis for enhancing students' ability to learn. Re-aligned course objectives should focus especially in critical areas such as professional writing, oral expression, skills for working with others, analysis, synthesis, evaluation, and application of concepts in novel, ambiguous, and real-world situations. Course content relating to professional ethics and personal integrity in the field are considered foundational to enhancing student critical thinking and understanding of realworld applications. This principle must be evaluated in the context of the course level, the departmental curriculum, and external standards regarding critical areas of content. Instructors give careful consideration to involving students in the local, professional, or global community in order to foster "stewardship of place", assist students in seeing how theory is applied in real settings, and to provide real service that benefits both student learning and the community. Engaged instructors recognize that students need to be able to understand diverse perspectives, cultural values, and to value differences in ideas and approaches in order to work effectively with others and find creative new solutions to real problems. This can be accomplished in multiple ways, but includes assignments that require participation in co-curricular campus events, community or global engagement or service learning opportunities and by mentoring students in conducting original research that contributes to the community, the profession, or the world. Instructors may also recommend and assist students in Study Abroad opportunities and other opportunities for global participation. The instructor ensures that students have basic skills and understand how to learn effectively and then builds on that foundation with policies, course activities and assignments that ask students to reflect on their learning, self-assess their progress and take responsibility for their learning. Critical how to learn skills include active reading (via SQ4R: Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review, wRite or other active reading methods), learning approaches (surface vs deep), time management, concept maps, technological literacy, self- and peer-assessment and discipline-specific skills necessary for success in higher level courses. The implementation of rubrics that inform students of what is expected in course assignments fosters personal responsibility for student learning. Course activities and assignments enable students to evaluate their own progress in achieving course objectives and mastery of the material. The instructor de-emphasizes his or her role as an exclusive content expert and designs course activities and assignments that require active engagement by the students with course material. Typically, the instructor will be personally engaged with individual students or groups of students and will be focused on encouraging, clarifying, and assisting students to discover core content principles rather than on just telling them information. This shift has been described as the “guide on the side” as opposed to the “sage on the stage.” This principle does not indicate a ban on lecturing; there are times when lecturing is an appropriate method, especially when used to respond to student questions or confusion or use of “mini-lectures”, but lecturing per se is not generally considered a form of engaged learning. Other examples include POGIL (Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning), collaborative or team-based learning, inquiry learning, problem based learning, Think-Pair-Share (especially in large classes), and adapting instruction to student learning styles. The instructor integrates assessment methods into the student learning process by using formative assessment to encourage students to learn from mistakes, develop skills, and increase self-awareness of areas they need to improve. Formative assessments also provide feedback to the instructor on the effectiveness of methods used and should lead to course modifications during the semester and over time. Examples include the use of rubrics, peer and self-assessments, and group exams. This principle needs to be evaluated in the context of class size, teaching loads, and available instructor support. Updated February, 2011 p.3 A sampling of relevant references: Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2002, July). Greater Expectations: A New Vision for Learning as a Nation Goes to College, National Panel Report. Available from: www.greaterexpectations.org/pdf/gex.final.pdf Barr, R.B. & Tagg, J. (1995, November/December). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change, 27, 12-25. Blumberg, P. (2009). Developing Learner-Centered Teaching: A Practical Guide for Faculty. San Franscisco: Jossey-Bass. Bransford, J., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (Eds.) (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experiences, and School. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. DeZure, D. (2000). Learning From Change. Sterling, VA: Stylus. Doherty, .A., Riordan, T., & Roth, J. (2002). Student Learning: A Central Focus for Institutions of Higher Education. Milwaukee, WI: Alverno College Institute. Doyle, T. (2008). Helping Students Learn in a Learner-Centered Environment. Sterling, VA: Stylus. Fink, L.D. (2003). Creating Significant Learning Experiences. San Franscisco: Jossey-Bass. Gardiner, L.F. (1994). Redesigning Higher Education: Producing Dramatic Gains in Student Learning. Washington, DC: Graduate School of Education and Human Development, The George Washington University. Jensen, E. (2005). Teaching with the Brain in Mind (2nd Ed). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Lazerson, M., Wagener, U., & Shumanis, N. (2000). What makes a revolution? Teaching and learning in higher education, 1980-2000. Change, 32(3), 12-19. Mullin, R. (2001). The undergraduate revolution: Change the system or give incrementalism another 30 years? Change, 33(5), 54-58. National Research Council. (2000). Educating Teachers of Science, Mathematics, and Technology: New Practices for the New Millenium. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Naitonal Research Council. (2001). Knowing What Students Know: The Science and Design of Educational Assessment. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. National Research Council. (2003). Evaluating and Improving Undergraduate Teaching in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Committee on Recognizing, Evaluating, Rewarding, and Developing Excellence in Teaching of Undergraduate Science, Mathematics, Engineering and Technology, M.A. Fox and N. Hackerman, Editors. Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Stage, F.K., Muller, P.A., Kinzie, J., & Simmons, A. (1998). Creating Learner Centered Classrooms: What Does Learning Theory Have to Say? Washington, DC: Clearinghouse on Higher Education and the Association for the Study of Higher Education. Tagg, J. (2003). The Learning Paradigm College. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing Company, Inc. Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.