Syllabus - Connect

advertisement

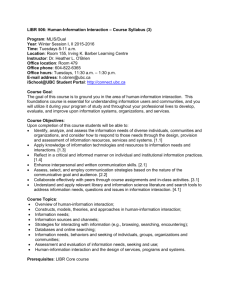

LIBR 506: Human-Information Interaction – Course Syllabus (3) Program: MLIS Year: Winter Session I, II 2015-2016 Time: Tuesdays 8-11 a.m. Location: Room 155, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre Instructor: Dr. Heather L. O’Brien Office location: Room 479 Office phone: 604-822-6365 Office hours: TBA E-mail address: h.obrien@ubc.ca iSchool@UBC Student Portal: http://connect.ubc.ca Course Goal: The goal of this course is to ground you in the area of human-information interaction. This foundations course is essential for understanding information users and communities, and you will utilize it during your program of study and throughout your professional lives to develop, evaluate, and improve upon information systems, organizations, and services. Course Objectives: Upon completion of this course students will be able to: Identify, analyze, and assess information needs of diverse individuals, communities and organizations, and consider how to respond to those needs through the design, provision and assessment of information resources, services and systems. [1.1] Apply knowledge of information technologies and resources to the information needs and interactions of a real-world information client. [1.3] Reflect in a critical and informed manner on individual and institutional information practices. [1.4] Articulate ideas and concepts fluently and thoughtfully in oral and written communications. [2.1] Assess, select, and employ communication and instructional tools based on an understanding of diverse communicative goals and audiences. [2.2] Demonstrate leadership, initiative, and effective collaboration with peers and an identified client. [3.1] Synthesize and apply the research and professional literature to identify and analyze significant theoretical and practical questions and issues in information interaction. [4.1] Course Topics: Overview of human-information interaction; Constructs, models, theories, and approaches in human-information interaction; Information needs; Information sources and channels; Strategies for interacting with information (e.g., browsing, searching, encountering); Database and online searching; Information needs, behaviors and seeking of individuals, groups, organizations and communities; Assessment and evaluation of information needs, seeking and use; Human-information interaction and the design of services, programs and systems. Prerequisites: LIBR Core course Format of the course: This course will involve lectures, class discussions and activities, individual and group work, and instructor-, peer-, and self-assessment. Required and Recommended Reading Journal and conference papers available through UBC Libraries will be assigned (see course schedule for weekly readings). Readings may be drawn from the following texts. Case, D.O. (2012). Looking for Information: A Survey of Research on Information Seeking, Needs and Behavior. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [2012 on print reserve at IKBLC; 2002 e-book] Fidel, R. (2012). Human Information Interaction: An Ecological Approach to Information Behavior. MIT Press. [On print reserve at IKBLC AND e-book] Fisher, K.E., Erdelez, S. & McKechnie, L.E.F. (2005). Theories of Information Behavior. American Society for Information Science and Technology. [On print reserve at IKBLC] Nahl, D. & Bilal, D. (2007). Information and Emotion: The Emergent Affective Paradigm in Information Behaviour Research. Medford, NJ: Information Today. [On print reserve at IKBLC] Spink, A. & Heinström, J. (Eds.). (2011). New Directions in Information Behaviour. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [On print reserve at IKBLC] Course Assignments: Assignment Participation: Contribution to class discussion, participation in group activities 1. In-class search assignment Due date Throughout term Oct. 20 2. Term project (2-3 students) Oct. 13 Dec. 8 Weight 15% Reflection – 15% Peer Assessment – 10% Part 1, written report of information client and need (group) – 20% Part 2, report to client (group) – 20% Part 2, reflection (individual) – 20% *All written assignments must use APA style format. Participation: This grade is determined by meaningful contributions to the class in the context of discussions and inclass activities. Failure to attend class may result in a lower class grade. In-class activities may be evaluated for up to 5% of students’ participation grade. There will be more than one evaluated activity and students’ best mark will be counted toward their final grade. Assignment 1 - In-class search assignment: This assignment will allow you to act as information intermediaries in the search process, and you will have the ability to use and consider the utility of various information resources and tools. Specifically, you will: Identify, analyze, and assess the information needs of a classmate; Apply knowledge of information technologies and resources to the classmate’s information need; Articulate ideas and concepts fluently and thoughtfully in oral and written communications with the classmate and instructor; Demonstrate initiative and effective collaboration in this team-based assignment. You will be asked to prepare (in advance of class) three personal information searches based on specified criteria. These three searches will be brought to class for the assignment. You will be asked to articulate to your partner: the nature of the search; your motivation or interest in searching for the information; and its intended use or purpose. You will draw from our class on the reference interview for this assignment, and this is an opportunity to practice this skill. During class, you will be paired with a classmate. Each of you will take on the role of the intermediary (searching on behalf of another person) and the client. At the beginning of the exercise, you will conduct brief interviews with each other, where the intermediary is intended to clarify the client’s information needs and identify further details about the searches as relevant. Following the interview, you will conduct independent searches on behalf of your partner using a variety of resources. Intermediaries must save all relevant queries, search strategies, and results pages. You can do this by utilizing features within databases, screen captures, etc. Following the search period, you will regroup with your partner and share the findings of your respective searchers. Intermediaries should make notes about clients’ responses to their search results. You will submit TWO deliverables for this assignment, one as the “intermediary” and one as the “client”. Deliverable: “Intermediary” (1500-2000 words): An overview of your search strategy for one of the three searches, including keywords or queries, resources consulted, etc. A reflection describing 1) your experience acting as a search intermediary, 2) the high points and challenges you encountered during the activity, 3) advantages and limitations of the resources and search tools you consulted in relation to the specified search, and 4) your perception of whether you adequately addressed your client’s need and your rationale for this assessment. This is worth 15% toward the intermediary’s grade. Deliverable: “Client” (questionnaire): An assessment of the intermediary’s performance, based on a questionnaire developed by the instructor. This will take into account the intermediary’s effectiveness in communicating before and after the search, your level of satisfaction with the search results, and your evaluation of the intermediary’s strategy or approach to the information searches. The questionnaire will include open-ended and closed-ended questions. This will be shared with your intermediary to provide him/her valuable feedback. As such, it should be fair and detailed in terms of your partner’s strengths and areas for improvement. This is worth 10% of the client’s grade – you are being graded your ability to deliver constructive and meaningful feedback in a professional manner. Assignment 2 - Identifying and facilitating information needs (in pairs) The purpose of this assignment is to enable you to apply knowledge and skills gained in the course to an interaction with a real client. 1. Identification of an information client and his/her/their information need(s) You will identify and meet with an information client. The client must be willing to share a current information need and meet with you at least twice during the term. The need should be substantial (beyond looking up a fact or figure) in order to complete this assignment. (Note: This cannot be a search for another students’ academic assignment where the search results are being graded as part of a larger project for that student.) Deliverable (2500-3500 words) [group]: Provide a written description of the individual(s), including their demographic characteristics, e.g., age, gender, employment status, etc. and other variables that may be important in the context of the client’s information need, such as their subject or technological expertise, the nature of their work, etc. Describe the current information need that the client has articulated for you. Situate the above in the research literature. For example, if your client is a health professional, what does the scholarly and professional literature suggest about the information motivations and needs of his/her professional group, and/or the sources, channels, and strategies utilized when interacting with information? 2. Information search exercise Conduct an information search to satisfy the client’s information needs. Meet with the client to share the results. Deliverables (TOTAL 4000-5000 words): Written report to the client indicating your query terms, tools used, search strategies, and findings. This should be depicted in a way that can be easily digested by the client, and this will be highly dependent upon the client in terms of use of your use technical terms or jargon. For example, a legal search conducted for a lawyer will require a different approach than assisting a non-legal professional with such a search (2000-2500 words) [group component]. Personal reflection on the assignment. What did you learn by sharing the results of your search with the client? What would you change, if anything, about your search strategy or approach? Based on your literature review in deliverable 1, what was confirmed within this body of work when compared to your interactions with the client? What discrepancies did you note about the client and the literature you examined that “typified” your client? (2000-2500 words) [individual component]. Weekly Schedule and Readings Week Date 1 September 15 Topic Syllabus and course introduction 2 September 22 3 September 29 Historical overview; constructs, models, theories, and approaches Information needs, sources, channels and strategies 4 October 6 Seeking for others: The reference interview and introduction to database and online Readings Case (2012). Chapter 1 Fidel, R. (2012). What is human information interaction? Human Information Interaction: An Ecological Approach to Information Behavior (pp. 1743). MIT Press. Marchionini, G. (2008). Human-information interaction research and development. Library and Information Science Research, 30(3), 165–174. Case (2012). Chapter 6 and 7 Case (2012). Chapter 4 Ross, C. S. (1999). Finding without seeking: the information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 783-799. Savolainen, R. (2007). Information behavior and information practice: Reviewing the “umbrella concepts” of information-seeking studies. Library Quarterly, 77(2), 109–132. Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 42(5), 361–371. searching Guest Lecture with Dr. Luanne Freund 5 October 13 Other concepts and outcomes of interest in human-information interaction 6 October 20 In-class search assignment October 27 Human-information interaction: individuals – Work-related HII and “Everyday Life Information Seeking (ELIS)” 7 8 November 3 Human-information interaction: tasks and organizations 9 November 10 Human-information interaction: groups – Guest Lecture with Kelly Burke, Collaborative information behavior/retrieval Reference and User Services (RUSA) Guidelines: “Reference/Information Services” http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines Young, C.L. (2014) Crowdsourcing the Virtual Reference Interview with Twitter, The Reference Librarian, 55(2), 172-174. Case (2012). Chapter 5 Allard, S., Case, D. O., Andrews, J. E., & Johnson, J. D. (2005). Avoiding versus seeking: The relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 93(3), 353–362. McCay‐Peet, L., & Toms, E. G. (2015). Investigating serendipity: How it unfolds and what may influence it. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(7), 1463–1476. O'Brien, H. L., & Toms, E. G. (2008). What is user engagement? A conceptual framework for defining user engagement with technology. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(6), 938-955. No readings Case (2012). Chapter 11: Research by occupation. Case (2012). Chapter 12: Research by social role and demographic group. Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: Approaching information seeking in the context of ‘‘way of life’’. Library & Information Science Research, 17(3), 259–294. Bystrom, K. & Jarvelin, K. (1995). Task complexity affects information seeking and use. Information Processing & Management, 31(2), 191-213. Choo, C. W. (2001). Environmental scanning as information seeking and organizational learning. Information Research, 7(1), 7-1. Choo, C. W., Bergeron, P., Detlor, B., & Heaton, L. (2008). Information culture and information use: An exploratory study of three organizations. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(5), 792-804. Boehm, T., Klas, C.-P., & Hemmje, M. (2014). ezDL: Collaborative Information Seeking and Retrieval in a heterogeneous environment. Computer, 47(3), 32– 37. Hansen, P., & Järvelin, K. (2005). Collaborative Information Retrieval in an information-intensive domain. Information Processing & Management, 41(5), 1101–1119. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2004.04.016 Karunakaran, A., Reddy, M. C., & Spence, P. R. (2013). Toward a model of collaborative information behavior in organizations. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 10 November 17 Human-information interaction in the design of services, programs and systems 11 November 24 Assessing and evaluating humaninformation interaction 12 December 1 Ethics and professional standards for working with individuals and communities; Serving the needs of diverse individuals, groups and communities 64(12), 2437-2451. Marchionini, G. (1992). Interfaces for end-user information seeking. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 43(2), 156-163. Foss, E., Druin, A., Yip, J., Ford, W., Golub, E., & Hutchinson, H. (2013). Adolescent search roles. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(1), 173-189. Lloyd, A., Anne Kennan, M., Thompson, K. M., & Qayyum, A. (2013). Connecting with new information landscapes: information literacy practices of refugees. Journal of Documentation, 69(1), 121-144. Case (2012). Chapter 8: The research process. Case (2012). Chapter 9: Methods by type. Kelly, D., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2013). A systematic review of interactive information retrieval evaluation studies, 1967–2006. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(4), 745770. Griffis, M. R., & Johnson, C. A. (2013). Social capital and inclusion in rural public libraries: a qualitative approach. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, DOI=0961000612470277. Halbert, H. & Nathan, L.P. (2015). Designing for discomfort: Supporting critical reflection through interactive tools. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing ACM, New York, NY, 349360. Veinot, T. C. (2013). Regional HIV/AIDS information environments and information acquisition success. The Information Society, 29(2), 88-112. Course Policies Attendance: The calendar states: “Regular attendance is expected of students in all their classes (including lectures, laboratories, tutorials, seminars, etc.). Students who neglect their academic work and assignments may be excluded from the final examinations. Students who are unavoidably absent because of illness or disability should report to their instructors on return to classes.” Evaluation: All assignments will be marked using evaluative criteria given on the SLAIS web site. Written & Spoken English Requirement: Written and spoken work may receive a lower mark if it is, in the opinion of the instructor, deficient in English. Access & Diversity: Access & Diversity works with the University to create an inclusive living and learning environment in which all students can thrive. The University accommodates students with disabilities who have registered with the Access and Diversity unit: [http://www.students.ubc.ca/access/drc.cfm]. You must register with the Disability Resource Centre to be granted special accommodations for any on-going conditions. Religious Accommodation: The University accommodates students whose religious obligations conflict with attendance, submitting assignments, or completing scheduled tests and examinations. Please let your instructor know in advance, preferably in the first week of class, if you will require any accommodation on these grounds. Students who plan to be absent for varsity athletics, family obligations, or other similar commitments, cannot assume they will be accommodated, and should discuss their commitments with the instructor before the course drop date. UBC policy on Religious Holidays: http://www.universitycounsel.ubc.ca/policies/policy65.pdf . Academic Integrity Plagiarism The Faculty of Arts considers plagiarism to be the most serious academic offence that a student can commit. Regardless of whether or not it was committed intentionally, plagiarism has serious academic consequences and can result in expulsion from the university. Plagiarism involves the improper use of somebody else's words or ideas in one's work. It is your responsibility to make sure you fully understand what plagiarism is. Many students who think they understand plagiarism do in fact commit what UBC calls "reckless plagiarism." Below is an excerpt on reckless plagiarism from UBC Faculty of Arts' leaflet, "Plagiarism Avoided: Taking Responsibility for Your Work," (http://www.arts.ubc.ca/artsstudents/plagiarism-avoided.html). "The bulk of plagiarism falls into this category. Reckless plagiarism is often the result of careless research, poor time management, and a lack of confidence in your own ability to think critically. Examples of reckless plagiarism include: Taking phrases, sentences, paragraphs, or statistical findings from a variety of sources and piecing them together into an essay (piecemeal plagiarism); Taking the words of another author and failing to note clearly that they are not your own. In other words, you have not put a direct quotation within quotation marks; Using statistical findings without acknowledging your source; Taking another author's idea, without your own critical analysis, and failing to acknowledge that this idea is not yours; Paraphrasing (i.e. rewording or rearranging words so that your work resembles, but does not copy, the original) without acknowledging your source; Using footnotes or material quoted in other sources as if they were the results of your own research; and Submitting a piece of work with inaccurate text references, sloppy footnotes, or incomplete source (bibliographic) information." Bear in mind that this is only one example of the different forms of plagiarism. Before preparing for their written assignments, students are strongly encouraged to familiarize themselves with the following source on plagiarism: the Academic Integrity Resource Centre http://help.library.ubc.ca/researching/academic-integrity. Additional information is available on the SAIS Student Portal http://connect.ubc.ca. If after reading these materials you still are unsure about how to properly use sources in your work, please ask me for clarification. Students are held responsible for knowing and following all University regulations regarding academic dishonesty. If a student does not know how to properly cite a source or what constitutes proper use of a source it is the student's personal responsibility to obtain the needed information and to apply it within University guidelines and policies. If evidence of academic dishonesty is found in a course assignment, previously submitted work in this course may be reviewed for possible academic dishonesty and grades modified as appropriate. UBC policy requires that all suspected cases of academic dishonesty must be forwarded to the Dean for possible action.