Syllabus - Connect

advertisement

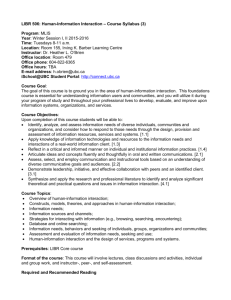

LIBR 506: Human-Information Interaction – Course Syllabus (3) Program: MLIS/Dual Year: Winter Session I, II 2015-2016 Time: Tuesdays 8-11 a.m. Location: Room 155, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre Instructor: Dr. Heather L. O’Brien Office location: Room 479 Office phone: 604-822-6365 Office hours: Tuesdays, 11:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. E-mail address: h.obrien@ubc.ca iSchool@UBC Student Portal: http://connect.ubc.ca Course Goal: The goal of this course is to ground you in the area of human-information interaction. This foundations course is essential for understanding information users and communities, and you will utilize it during your program of study and throughout your professional lives to develop, evaluate, and improve upon information systems, organizations, and services. Course Objectives: Upon completion of this course students will be able to: Identify, analyze, and assess the information needs of diverse individuals, communities and organizations, and consider how to respond to those needs through the design, provision and assessment of information resources, services and systems. [1.1] Apply knowledge of information technologies and resources to information needs and interactions. [1.3] Reflect in a critical and informed manner on individual and institutional information practices. [1.4] Enhance interpersonal and written communication skills. [2.1] Assess, select, and employ communication strategies based on the nature of the communicative goal and audience. [2.2] Collaborate effectively with peers through course assignments and in-class activities. [3.1] Understand and apply relevant library and information science literature and search tools to address information needs, questions and issues in information interaction. [4.1] Course Topics: Overview of human-information interaction; Constructs, models, theories, and approaches in human-information interaction; Information needs; Information sources and channels; Strategies for interacting with information (e.g., browsing, searching, encountering); Databases and online searching; Information needs, behaviors and seeking of individuals, groups, organizations and communities; Assessment and evaluation of information needs, seeking and use; Human-information interaction and the design of services, programs and systems. Prerequisites: LIBR Core course Format of the course: This course will involve lectures, class discussions and activities, individual and group work, and instructor-, peer-, and self-assessment. Required Reading Journal and conference papers available through UBC Libraries. Case, D.O. (2012). Looking for Information: A Survey of Research on Information Seeking, Needs and Behavior. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [Copies available at UBC Bookstore; on print reserve at IKBLC] The following texts contain required course readings, and works that may be useful for assignments or additional learning. Fidel, R. (2012). Human Information Interaction: An Ecological Approach to Information Behavior. MIT Press. [On print reserve at IKBLC AND e-book] Fisher, K.E., Erdelez, S. & McKechnie, L.E.F. (2005). Theories of Information Behavior. American Society for Information Science and Technology. [On print reserve at IKBLC] Nahl, D. & Bilal, D. (2007). Information and Emotion: The Emergent Affective Paradigm in Information Behaviour Research. Medford, NJ: Information Today. [On print reserve at IKBLC] Ross, C.S., Nilsen, K. & Radford, M.L. Conducting the Reference Interview, Second Edition. New York: Neal-Shuman Publishers, Inc. [On print reserve at IKBLC] Spink, A. & Heinström, J. (Eds.). (2011). New Directions in Information Behaviour. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [On print reserve at IKBLC] Supplemental Resources UBC Library Tutorials for conducting basic, advanced, and subject-specific searching and using library materials: http://help.library.ubc.ca/planning-your-research/tutorials/ Google search education, Power searching online modules http://www.powersearchingwithgoogle.com/course/aps Vancouver Public Library Subject Guides http://guides.vpl.ca and video tutorials https://www.youtube.com/user/vancouverlibrary/videos Weekly Schedule and Readings Week Date Topic Readings 1 Jan Syllabus Case (2012). Chapter 1. Information behavior: An introduction. 5 Introduction Case (2012). Chapter 2. Common examples of information to the course behavior. Fidel, R. (2012). What is human information interaction? Human Information Interaction: An Ecological Approach to Information Behavior (pp. 17-43). MIT Press. 2 Jan The Reference and User Services (RUSA) Guidelines: 12 reference “Reference/Information Services - Guidelines for Behavioral interview Performance of Reference and Information Service Providers” http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines Ross, C.S., Nilsen, K. & Radford, M.L. Conducting the Reference Interview, Second Edition. New York: NealShuman Publishers. Chapter 1: Why bother with a reference interview? (pp. 1-37) Chapter 2: Setting the stage for the reference interview (pp. 39-67) 3 Jan 19 4 Jan 26 5 Feb 2 Feb 9 6 7 81 Chapter 3: Finding out what they really want to know (pp. 69-109) Introduction Liddy, E. (2001). How a search engine works. Searcher, 9(5), to information 38-45. searching; Hendry D. & Efthimiadis E. (2008). Conceptual models for Introduction search engines. In Spink A. & Zimmer M. (Eds.) Web to UBC searching: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 277-308). Berlin: Library Springer. resources Fidel, R. (2012). Five search strategies. Human Information Erin Fields Interaction: An Ecological Approach to Information Behavior (pp. 97-118). MIT Press. Approaching Feldman, S.E. (2012). The Answer Machine. Synthesis complex Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services searches (137 pp.), DOI:10.2200/S00442ED1V01Y201208ICR023. Erin Fields In-class search assignment Information needs & needs assessment Feb 16 Feb 23 Winter Break Mar 1 Information seeking, searching, browsing and avoidance - Reading Case (2012). Chapter 4. Information needs and information seeking. Case (2012). Chapter 11: Research by occupation. Case (2012). Chapter 12: Research by social role and demographic group. Fidel, R. (2012). Information need and the decision ladder. Human Information Interaction: An Ecological Approach to Information Behavior (pp. 83-96). MIT Press. Working Together Project. The Community-Led Libraries Toolkit. Working Together Project website. Available: http://www.librariesincommunities.ca/resources/CommunityLed_Libraries_Toolkit.pdf Hupfeld, A., Sellen, A., O’Hara, K., & Rodden, T. (2013). Leisure-based reading and the place of e-books in everyday life. In Human-Computer Interaction–INTERACT 2013 (pp. 118). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Hillesund, T. (2010). Digital reading spaces: How expert readers handle books, the web and electronic paper. First Monday 15(4–5). Available: http://firstmonday.org/article/view/2762/2504 Ross, C. S. (1999). Finding without seeking: the information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 783-799. Recommended: Pearson, J., Buchanan, G., & Thimbleby, H. (2013). Designing for Digital Reading. Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services, 5(4), (135 pp). Allard, S., Case, D. O., Andrews, J. E., & Johnson, J. D. (2005). Avoiding versus seeking: The relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 93(3), 353–362. Kelly Burke 9 Mar 8 Evaluating information sources, services and systems 10 Mar 15 Health Information Practices Dr. Devon Greyson 11 Mar 22 Academic Information Practices Case (2012). Chapter 5. Related concepts Fidel, R. (2012). Theoretical constructs and models in information seeking behavior. Human Information Interaction: An Ecological Approach to Information Behavior (pp. 49-82). MIT Press. Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 42(5), 361– 371. Marchionini, G., Plaisant, C., & Komlodi, A. (2003). The people in digital libraries: Multifaceted approaches to assessing needs and impact. Digital library use: Social practice in design and evaluation, 119-160. [UBC Library e-Book] Nielsen, J. & Molich, R. (1990). Heuristic evaluation of user interfaces. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '90). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 249-256. DOI=http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/97243.97281 Zhang, Y. & Deng, S. (2014). Social question and answer services versus library virtual reference: evaluation and comparison from the users' perspective. Information Research 19(4). Available http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-4/paper650 Reference and User Services (RUSA) Guidelines: “Reference/Information Services – Health and Medical Reference Guidelines” http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines Zhang, Y. (2014), Beyond quality and accessibility: Source selection in consumer health information searching. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65, 911–927. doi: 10.1002/asi.23023 Borgman, C.L. Darch, P.T., Sands, A.E., Pasquetto, I.V., Golshan, M.S., Wallis, J.C. & Traweek, S. (2015). Knowledge infrastructures in science: data, diversity, and digital libraries. International Journal on Digital Libraries, 16(3), 207-227. Head, A.J. (December 4, 2013). Learning the ropes: How freshmen conduct course research once they enter college, http://projectinfolit.org/images/pdfs/pil_2013_freshmenstudy_f ullreport.pdf Palmer, C. L., Teffeau, L. C., & Pirmann, C. M. (2009). Scholarly information practices in the online environment: Themes from the literature and implications for library service development. Dublin, OH: OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. 12 Mar 29 13 Apr 5 Collaborative information seeking & retrieval – Kelly Burke Hansen, P., & Järvelin, K. (2005). Collaborative information retrieval in an information-intensive domain. Information Processing & Management, 41(5), 1101–1119. Karunakaran, A., Reddy, M. C., & Spence, P. R. (2013). Toward a model of collaborative information behavior in organizations. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(12), 2437-2451. Twidale, M. B., Nichols, D. M., & Paice, C. D. (1997). Browsing is a collaborative process. Information Processing & Management, 33(6), 761–783. Optional Reading: Boehm, T., Klas, C.-P., & Hemmje, M. (2014). ezDL: Collaborative information seeking and retrieval in a heterogeneous environment. Computer, 47(3), 32–37. Course wrap up and term project presentations Course Assignments: Assignment Participation: Contribution to class discussion, participation in group activities ASSIGNMENT 1: In-class search assignment (to take place on February 2) ASSIGNMENT 2: Search task assignment ASSIGNMENT 3: Term Project (GROUP) Proposal Presentation Report/Product Due date Throughout term February 9 February 12 March 8 Weight 10% January 26 April 5 April 8 5% 10% 25% Peer Assessment – 10% Reflection – 20% 20% * Notes about assignments: All written assignments must use APA style format. All submitted files should be labeled with your last name(s) and the name of the assignment. o For example: Lastname(s)_Assignment1_ClientDeliverable. Assignments in Detail Participation This grade is determined by meaningful contributions to the class in the context of discussions and in-class activities. Failure to attend class may result in a lower class grade. Assignment 1: In-class search assignment This assignment will allow you to act as information intermediaries in the search process, and you will have the ability to use and consider the utility of various information resources and tools. Specifically, you will: Identify, analyze, and assess the information needs of a classmate; Apply knowledge of information technologies and resources to the classmate’s information need; Articulate ideas and concepts fluently and thoughtfully in oral and written communications with the classmate and instructor; Demonstrate initiative and effective collaboration in this team-based assignment. You will be asked to prepare (in advance of class) three personal information searches based on specified criteria. These three searches will be brought to class for the assignment. You will be asked to articulate to your partner: the nature of the search; your motivation or interest in searching for the information; and its intended use or purpose. You will draw from our classes on the reference interview and information searching for this assignment, and this is an opportunity to practice interpersonal, interviewing, and searching skills. During class, you will be paired with a classmate. Each of you will take on the role of the intermediary (searching on behalf of another person) and the client. You will conduct brief interviews with each other, where the intermediary is intended to clarify the client’s information needs and identify further details about the searches as relevant. Following the interview, you will conduct independent searches on behalf of your partner using a variety of resources. Intermediaries must save all relevant queries, search strategies, and results pages. You can do this by utilizing features within databases, screen captures, etc. Following the search period, you will regroup with your partner and share the findings of your respective searchers. Intermediaries should make notes about clients’ responses to their search results. You may choose to work on one information need at a time, or all three, though it is best to ensure you have at least one complete search to report on for your reflection assignment (see below); you do not want to run out of time or feel rushed. Some partners may choose to search independently or consult each other during the process to clarify aspects of the search, show each other some preliminary results, etc. Communicate your preferences with your partner in advance of beginning. You will submit TWO deliverables for this assignment, one as the “intermediary” and one as the “client”. Deliverable: “Intermediary” (1500-2000 words): An overview of your search strategy for one of the three searches, including keywords or queries, resources consulted, etc. A reflection describing 1) your experience acting as a search intermediary, 2) the high points and challenges you encountered during the activity, 3) advantages and limitations of the resources and search tools you consulted in relation to the specified search, and 4) your perception of whether you adequately addressed your client’s need and your rationale for this assessment. Deliverable: “Client” (questionnaire): An assessment of the intermediary’s performance, based on a questionnaire developed by the instructor. This will take into account the intermediary’s effectiveness in communicating before and after the search, your level of satisfaction with the search results, and your evaluation of the intermediary’s strategy or approach to the information searches. The questionnaire will include open-ended and closed-ended questions. This will be shared with your intermediary to provide him/her with valuable feedback. As such, it should be fair and detailed in terms of your partner’s strengths and areas for improvement. You are being graded your ability to deliver constructive and meaningful feedback in a professional manner. Assignment 2: Search Task Assignment The purpose of this assignment is to gain further experience utilizing search tools to address complex search tasks. You will be provided with a list of multi-facets search tasks and asked to select two from the list for this assignment. These will be available on Connect in the “Assignments” section of the site. You should use a variety of resources for each search task, comparing how, for example, a search engine compares to an academic database, or a public library database for reader’s advisory compares with GoodReads, or CINAHL versus a consumer health resource such as the Mayo Clinic. This will give you an appreciation of how the same search can be approached differently and whether each produces different results. Deliverable (2000-2500 words): For each of the two search tasks you must provide a summary report of your search process and outcome. This should include: Your approach to the task, including how you broke the search down into manageable parts and search strategies you employed during the task (e.g., general to specific, pearl growing, etc.); The resources you used, and how you used them (e.g. database thesauri or index, applying limiters, use of Boolean operators); Decisions that you made regarding the relevance of items, alterations in what or how you were searching, and how you confirmed or triangulated your information; Comparison of each of the tools used with regards to their benefits and drawbacks related to the search; Conclusion in terms of how well you addressed the search task, and challenges or uncertainties encountered uncertainty. If this search was being conducted for someone else, would you hand it off to the client and why/why not? Assignment 3: Term Project The purpose of this project is to design an information resource, system or service for a specific user community. This could take the form of: a tutorial, program, workshop, subject guide, website, app, finding aid, online community, etc. You will work in groups of 3* people to decide what you are designing, who it is for, and the mode through which it will be delivered (in person, on the web via a library portal or YouTube, etc.). * Groups of 2 are permissible but not groups larger than 3. You cannot work alone. Deliverables Proposal (500-750 words) Who are the members of the team? What are you designing? Who is the intended information user or audience? How will the resource, system, or service be delivered to the user community? What form will it take? Why is this appropriate? What will each member of the team be contributing to the project? Timeline for completing the project by the end of term, including goals and objectives for each segment. Presentation Students will present their designs and ideas in the final class. All members of the team must participate in a meaningful way. Presentations can take any form, and may depend on the product. It should, however, be clear, who the intended user or audience of the program/service/system is, the motivation for its creation (i.e., why is this a good idea), and how it works/what it is meant to accomplish. The time devoted to presentations will depend on the number of projects and the class time available. We will work out this detail and the schedule closer to the end of the term. Report/Product (3000-4000 words) The final deliverable should include: A description of the program/system/service and the motivation for its creation. A supporting argument, drawn from the research literature (8-12 sources), regarding the need for this information resource/system/service within this specific user community. For example, if you design an information portal for children, you should utilize the research literature around how children seek and use information to inform your decision-making about the portal’s design features or navigation structure. Ensure you connect the “what” (product) with the “who” (user group, community). The designed system/service/program. This can take the form of: a video, a lesson plan for a program, a simple website, a paper mock up of an online system. There should be enough context for the reader/viewer to understand what the product is, how it works, and what it is intended to accomplish. Course Policies Attendance: The UBC calendar states: “Regular attendance is expected of students in all their classes (including lectures, laboratories, tutorials, seminars, etc.). Students who neglect their academic work and assignments may be excluded from the final examinations. Students who are unavoidably absent because of illness or disability should report to their instructors on return to classes.” Evaluation: All assignments will be marked using the evaluative criteria given on the SLAIS web site. Written & Spoken English Requirement: Written and spoken work may receive a lower mark if it is, in the opinion of the instructor, deficient in English. Access & Diversity: Access & Diversity works with the University to create an inclusive living and learning environment in which all students can thrive. The University accommodates students with disabilities who have registered with the Access and Diversity unit: [http://www.students.ubc.ca/access/drc.cfm]. You must register with the Disability Resource Centre to be granted special accommodations for any on-going conditions. Religious Accommodation: The University accommodates students whose religious obligations conflict with attendance, submitting assignments, or completing scheduled tests and examinations. Please let your instructor know in advance, preferably in the first week of class, if you will require any accommodation on these grounds. Students who plan to be absent for varsity athletics, family obligations, or other similar commitments, cannot assume they will be accommodated, and should discuss their commitments with the instructor before the course drop date. UBC policy on Religious Holidays: http://www.universitycounsel.ubc.ca/policies/policy65.pdf. Academic Integrity Plagiarism The Faculty of Arts considers plagiarism to be the most serious academic offence that a student can commit. Regardless of whether or not it was committed intentionally, plagiarism has serious academic consequences and can result in expulsion from the university. Plagiarism involves the improper use of somebody else's words or ideas in one's work. It is your responsibility to make sure you fully understand what plagiarism is. Many students who think they understand plagiarism do in fact commit what UBC calls "reckless plagiarism." Below is an excerpt on reckless plagiarism from UBC Faculty of Arts' leaflet, "Plagiarism Avoided: Taking Responsibility for Your Work," (http://www.arts.ubc.ca/arts-students/plagiarismavoided.html). "The bulk of plagiarism falls into this category. Reckless plagiarism is often the result of careless research, poor time management, and a lack of confidence in your own ability to think critically. Examples of reckless plagiarism include: Taking phrases, sentences, paragraphs, or statistical findings from a variety of sources and piecing them together into an essay (piecemeal plagiarism); Taking the words of another author and failing to note clearly that they are not your own. In other words, you have not put a direct quotation within quotation marks; Using statistical findings without acknowledging your source; Taking another author's idea, without your own critical analysis, and failing to acknowledge that this idea is not yours; Paraphrasing (i.e. rewording or rearranging words so that your work resembles, but does not copy, the original) without acknowledging your source; Using footnotes or material quoted in other sources as if they were the results of your own research; and Submitting a piece of work with inaccurate text references, sloppy footnotes, or incomplete source (bibliographic) information." Bear in mind that this is only one example of the different forms of plagiarism. Before preparing for their written assignments, students are strongly encouraged to familiarize themselves with the following source on plagiarism: the Academic Integrity Resource Centre http://help.library.ubc.ca/researching/academic-integrity. Additional information is available on the Connect site http://connect.ubc.ca. If after reading these materials you still are unsure about how to properly use sources in your work, please ask me for clarification. Students are held responsible for knowing and following all University regulations regarding academic dishonesty. If a student does not know how to properly cite a source or what constitutes proper use of a source it is the student's personal responsibility to obtain the needed information and to apply it within University guidelines and policies. If evidence of academic dishonesty is found in a course assignment, previously submitted work in this course may be reviewed for possible academic dishonesty and grades modified as appropriate. UBC policy requires that all suspected cases of academic dishonesty must be forwarded to the Dean for possible action.