The terms hypothesis and prediction are

advertisement

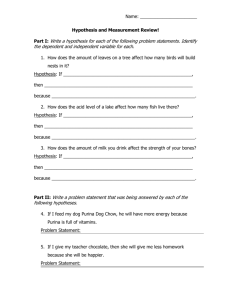

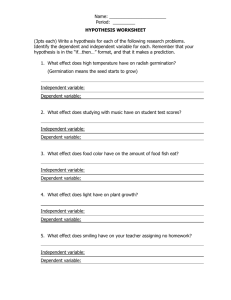

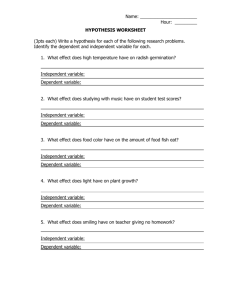

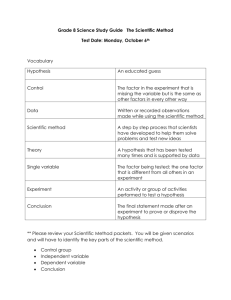

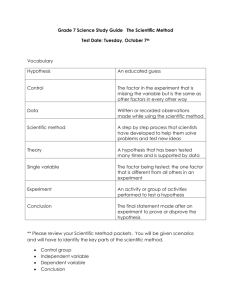

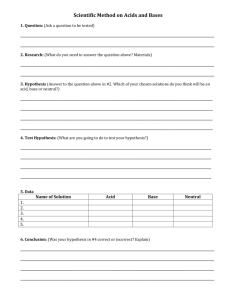

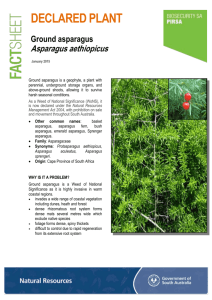

Understanding Hypotheses and Predictions The terms hypothesis and prediction are sometimes used interchangeably, but it’s important to understand the difference and include them as distinct statements in the lab report. Research Question Before we get to the hypothesis, we must start at the beginning of the research process, known as the scientific method, with a research question. Research questions often stem from observations – these observations can be made in passing, or they might come as a result of previous research. For example, while out bird watching, you notice that a certain species of sparrow made all of its nests with the same material: grasses. From that observation, you might wonder, “Why are the nests of sparrows made with grasses rather than twigs?” This is your research question. Hypothesis A hypothesis is, in simple terms, the answer to your research question. From your question about sparrow nests, you would derive a hypothesis based on your background research. You might hypothesize, “Sparrows use grasses in their nests rather than twigs because grasses are the more abundant material in their habitat.” Prediction A prediction, on the other hand, is specific to the study and experiment that you design to test your hypothesis. It’s the outcome you would observe if your hypothesis were supported. Predictions are often written in the form of “if, then” statements, as in, “if my hypothesis is true, then this is what I will observe.” Following our example, you could design an experiment wherein birds are provided with differing quantities of the two nest materials, and you could predict that, “If sparrows use grasses in their nests rather than twigs because grasses are the more abundant material in their habitat, then when twigs are more abundant, sparrows will use those in their nests.” A more refined prediction might alter the wording so as not to repeat the hypothesis verbatim: “If sparrows choose nesting materials based on their abundances, then when twigs are more abundant, sparrows will use those in their nests.” Example Let’s take a look at another example: Hypothesis: When planted alongside asparagus, marigolds will deter asparagus beetles. Prediction: If marigolds deter asparagus beetles, then asparagus plants planted alongside marigolds will host fewer asparagus beetles than asparagus plants planted on their own. A final note Resist the urge to change your hypotheses and predictions based on the outcome of your study or experiment. Your work will not be negated (or marked down) because you didn’t find what you had expected. To the contrary, an unexpected result often provides more area for discussion – consider what about your background research led you to your hypotheses and predictions and discuss why your research had an unpredicted outcome. The Academic Skills Centre Trent University www.trentu.ca/academicskills acdskills@trentu.ca 705-748-1720