Multi-morbidity, goal-oriented care and equity

advertisement

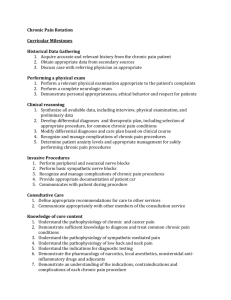

Multi-morbidity, goal-oriented care and equity. James Mackenzie lecture 2011. Prof. J. De Maeseneer, MD, Ph.D., FRCGP (Hon)1, Pauline Boeckxstaens, MD, PhD-student2. 1, 2 Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, International Centre for Primary Health Care and Family Medicine – Ghent University, WHO Collaborating Centre on Primary Health Care. 1, 2 General practitioner, Community Health Center "Botermarkt", Ledeberg – Gent. 1 Vice-dean Strategic Planning Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ghent University. 1 Chairman European Forum for Primary Care (www.euprimarycare.org) and Secretary-General The Network: Towards Unity for Health (www.the-networktufh.org) Introduction. James Mackenzie (°1853) was a famous general practitioner who spent a major part of his practice life in Burnley, an industrial town in the north of England. He was a great clinician with the skill of detailed observation that underpins, even nowadays, any scientific activity. Already in 1907, when opening the Leeds post graduate course, he stressed the central role of the general practitioner in observing and managing chronic disease throughout its course. Hereby, James Mackenzie was probably one of the first to think of epidemiology in terms of non-infectious diseases. Today it is clear that we face an important demographic and epidemiological transition, confronting us with the challenge of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which occur more and more in the context of multi-morbidity. In the next decade, multi-morbidity will become the rule, no longer the exception. We explore the presentation of multi-morbidity in an international context and describe how patients with multi-morbidity are approached today. We will argue for the need for a paradigm-shift from problem-oriented to goal-oriented care, which requires new types of evidence and research, and finally we will try to integrate this development into the perspective of quality and equity in health. Presentation of multi-morbidity in an international context. Apart from the deaths caused by infectious diseases, the number of people dying as a result of noncommunicable diseases has risen to 36.1 million per year worldwide. This means that for the moment almost 2 of 3 deaths are attributable to NCDs 1. For adults this is even 3 in 4. NCDs are not merely a problem of the wealthy aged. Most of these deaths arise in the poorest countries (22.4 million) and 63% of premature deaths in adults (age 15-69 years) are attributable to NCDs. 1 Especially in developed countries, with increasing life expectancy, NCDs are more and more a phenomenon, accompanied by a rise in multimorbidity : 50% of the 65+ have at least 3 chronic conditions, whereas 20% of the 65+ have at least 5 chronic conditions2. In the case of COPD e.g. more than half of the patients have at least one comorbid disease3. In recent literature, this development is defined as an "NCD-crisis"4. However NCDs cannot be regarded as a completely separate problem. In HIV and AIDS several studies 5 6 7 have demonstrated an increased incidence of heart disease, diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, liver disease, osteoporosis, malignancies (other than the well known associated Kaposi’s sarcoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma), and possibly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease8 when HIV/AIDS patients were compared to age matched HIVuninfected controls. An observation which clearly creates important challenges for developing countries. Describing the rising prevalence of NCDs as a "crisis" makes for good drama, but misleads us into thinking that this problem is amenable to a quick fix. NCDs represent a set of chronic conditions, that will require a sustained effort for many decades. How do we address patients with multi-morbidity today? In recent years, not only Western countries, but also developing countries started with "chronic disease management-programs" in order to improve care. The design of those programs includes most frequently: strategies for case-finding, protocols describing what should be done and by whom, the importance of information and empowerment of the patient and the definition of process- and outcome-indicators that may contribute to the monitoring of care. Finally, incentives have been defined in order to stimulate both patients and providers to adhere to guidelines. This development has led to spectacular results e.g. in process- and outcome-indicators in the United Kingdom under the Quality and Outcomes Framework9. Moreover, the "chronic disease management"-approach has led to an acceleration of the implementation of the subsidiarity-principle in primary health care with important task-shifting from physicians, to nurses, dieticians, health educators,... In spite of some critical reflections with respect to equity10 11, to the sustainability of the quality improvement, and comprehensiveness versus reductionism12, in general, these programs have received positive feedback from providers, patients and politicians. Wagner has described the different components of the Chronic Care Model (CCM) as developed in the context of primary health care13. He emphasised the need for changes both at the level of health systems (through health care organisation) and at the community level (through resources and policies) with an emphasis on self-management support, delivery system design changes, and appropriate decision support in the context of clinical information systems. It is hoped that all these changes will lead to productive interactions between an informed, empowered patient and a prepared, pro-active practice team, in order to achieve improved outcomes. The CCM has inspired policy makers and providers all over the world and is widely accepted in North America, Europe and Australia. Taking into account the epidemiological transition, we are faced with the question: "How will this approach work in a situation of multimorbidity?" Let us illustrate this with a patient from our general practice, we call her "Jennifer". 2 In box 1 I describe the case of Jennifer. Box 1. Jennifer Jennifer is 75 years old. Fifteen years ago she lost her husband. She has been a patient at the practice for 15 years now. During these last 15 years she has been through a difficult medical history: hip replacement surgery for osteoarthritis, hypertension, diabetes type 2, and COPD. She lives independently at home, with some help from her youngest daughter, Elisabeth. I visit her regularly and each time she starts by saying: "Doctor, you must help me". Then follows a succession of complaints and feelings: Sometimes it has to do with her heart, another time with lungs, then the hip,… Each time I suggest – according to the guidelines – all sorts of examinations that do not improve her condition. Her request becomes more and more explicit, my feelings of powerlessness, inadequacy and irritation, increase. Moreover, I have to cope with guidelines that are contradictory: for COPD she sometimes needs corticosteroids, which always worsens her diabetes control. The adaptation of the medication for the blood pressure (once too high, once too low) does not meet with her approval, and nor does my interest in her HbA1C and lungfunction test-results. After so many contacts, Jennifer says: "Doctor, I want to tell you what really matters to me. On Tuesday and Thursday, I want to visit my friends in the neighbourhood and play cards with them. On Saturday, I want to go the supermarket with my daughter. Foremost, I just want some peace. I do not want to continually change the therapy anymore, especially not having to do this and to do that". In the conversation that followed, it became clear to me how Jennifer had formulated the goals for her life. At the same time I felt challenged to identify how the guidelines could contribute to the achievement of Jennifer's goals. I have visited Jennifer with pleasure ever since. I know what she wants and how much I can (merely) contribute to her life. According to the actual guidelines, Jennifer is faced with a lot of tasks14: joint protection, aerobic exercise, muscle strengthening, a range of motion exercising, self-monitoring of blood glucose, avoiding environmental exposure that might exacerbate COPD, wearing appropriate foot wear, limiting intake of alcohol, maintaining body weight. She has to receive patient education regarding diabetes selfmanagement, foot care, osteoarthritis and COPD medication delivery system training. Her medication 3 schedule includes 11 different drugs, with a total of 20 administrations a day. The clinical tasks for the general practitioner include vaccination, blood pressure control at all clinical visits, evaluation of selfmonitoring of blood glucose, foot examination, laboratory tests… Moreover, referrals are needed to physiotherapy, for ophthalmologic examination and pulmonary rehabilitation. So, Jennifer's reaction is not unexpected. Jennifer's case clearly illustrates the need for a paradigm-shift for chronic care: from Problem-Oriented to Goal-Oriented Care. In 1991, Mold and Blake15 recognised that the problem-oriented model, focusing on the eradication of disease and the prevention of death, is not well suited to the management of a number of chronic illnesses. Therefore they proposed a goal-oriented approach that encourages each individual to achieve the highest possible level of health as defined by that individual. This represents a more positive approach to health care, characterised by greater emphasis on individual strengths and resources. Goal-Oriented Care assists an individual in achieving their maximum individual health potential in line with their individually defined goals. The evaluator of success is the patient, not the physician. And, what really matters for patients is their ability to function (functional status), and social participation. So, certainly in the context of multi-morbidity, there is a need for a shift from "Chronic Disease Management" towards "Participatory Patient Management", with the patient at the centre of the process. Exploring the goals of patients will require new conceptual frameworks, new types of research and new research-designs and -methods. Nowadays, understanding self-determination and self-agency in relation to the disease, is highly valued by patients. For many people, giving meaning to the chronic illnessprocess they are going through, is of the utmost importance. Safety and avoiding side-effects (not having to suffer more from the treatment than from the disease) is very important. Patients expect comprehensiveness in their care instead of fragmentation. A recent survey of "chronic disease management" in 10 European countries illustrated that most of the countries chronic disease management programs are organised by the label of one chronic condition, sometimes focusing on subgroups, within a specific chronic disease16. The 5 conditions most frequently addressed are cancer, cardiovascular disease, COPD, depression and diabetes. Most of the programs use a vertical disease-oriented approach. Vertical disease-oriented programs, originated from the concept of "selective primary health care" that developed shortly after the Alma Ata Declaration. The idea was that a selective approach would attack the most severe public health problems facing a community in order to have the greatest chance to improve both health and medical care, especially in less developed countries17. Although much has been learnt from vertical disease-oriented programs, evidence suggests that better outcomes occur by addressing diseases through an integrated approach in a strong primary care system. An example is Brazil, where therapeutic coverage for HIV/aids reaches almost 100% which is much better than HIV/aids programs in other countries with less robust primary care18. Vertical disease oriented programs for HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases foster duplication and the inefficient use of resources, produce gaps in the care of patients with multi-morbidity, and reduce, especially in developing countries, government capacity by pulling the best health care workers out of the public health sector to focus on single diseases19. Moreover, vertical programmes cause inequity for patients who do not have the “right” disease20. Horizontal primary care provides the 4 opportunity for integration and addresses the problem of inequity, providing access to the care of all health problems, thereby avoiding "inequity by disease21. Need for new types of evidence: medical, contextual and policy evidence. Clinical decisions must be based on adequate knowledge of diseases (medical evidence) but at the same time, they must take into account patient-specific aspects of medical care (contextual evidence) and efficiency, equity and rationing (policy evidence)22. As far as medical evidence is concerned, within primary health care, we are confronted with the tension between the results of clinical research on the one hand and the needs of daily clinical practice on the other hand. The available research generally does not include a representative sample of patients with respect to age and ethnic origin or comorbidity, and does not take into account the typical non-specific presentation of symptoms at an early disease stage. As the case of Jennifer (see box 1) illustrates, within primary care, questions arise on which evidence to follow in the case of multimorbidity. Treatment according to the guidelines for one condition (corticosteroids for COPD) may interfere with the guidelines for another disease (glycemic control in diabetes type 2). There is a lot of evidence available on the treatment of COPD or the management of type 2 diabetes for patients younger than 75 years but there is little, if any, evidence about how to treat a 75-year old woman who has both or even additional disorders. This problem implies a need for research on the effectiveness of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions that take into account these aspects of patients in primary care. The challenge of multi-morbidity illustrates the lack of appropriate evidence. A basic assumption in the development of guidelines is that clinical research follows clinical relevance. In reality, a lot of research is driven by commercial interests23. A consequence is that the focus has shifted from "treat-the-patient" towards "treat-to-target". And in achieving the "target" much more evidence is available for pharmacological treatments than on the effects of interventions aimed at changing health behaviours. So, the threat in Evidence Based Medicine is pursuing what is possible and available, rather than what is relevant. If we want to take the goals of the patient into account, we need a new type of evidence: contextual evidence, to assist doctors in addressing the challenge of how to treat a particular patient in a specific situation. Contextual evidence deals with the principles of good doctor-patient communication in order to create trust in the interpersonal relationships, the exchange of pertinent information, exploration of the goals of the patient, and negotiation of treatment-related decisions. Communication training for doctors is only part of the story. Other factors that affect communication are related to the character and personality of both doctor and patient and their personal history (continuity of care), disease characteristics (life-threatening diseases, depression, chronic pain), actual goals in a specific life-cycle and family, socio-economic and cultural circumstances. It is difficult to imagine how exploration of the case of an individual patient may be reconciled with the need for the rigorous standardisation of a clinical encounter as required by the Randomised Controlled Trial. Another problem with RCTs is the design-related exclusion (e.g. patients with comorbidity) and the selective study dropout: patients from lower socio-economic status – in itself a barrier to 5 implementation of certain diagnostic and therapeutic strategies – might most frequently be lost to follow-up. Translation from research to practice presumes that patients are open to a "rational approach", take responsibility for their own health, and make their own informed decisions. Evidence Based Medicine depends in part on these factors, but many patients attribute their health status to external factors beyond their control (external health locus of control)24. Where research offers probabilities and numbers needed to treat, patients expect certainty from their physician, wanting to know whether the treatment will be successful for them. So, understanding contextual evidence is essential to bridging the gap between efficacy (what works in isolation and in an ideal setting) and effectiveness (what works in routine practice). In order to better understand the goals of the patients, new research frameworks and researchdisciplines will be needed. This will require input from disciplines that contribute to the understanding of provider-patient interaction such as medical philosophy, sociology and anthropology. Research methods will have to shift from purely quantitative (RCT) towards qualitative approaches (focusing on understanding through in-depth-interviews, focus groups, …). We will have to look for research-tools and approaches that focus on subjective determinants of well-being, and not only at biomedical parameters. In the new research-designs, patients with multi-morbidity will be the rule (instead of an exclusion criterion) and complexity will be embraced instead of avoided25. The International Classification of Function (ICF)26 might become as important as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), as it provides a conceptual framework in which different domains of human functioning are defined. These domains are classified from an eco-bio-psycho-social viewpoint by means of a list of body functions and structures, and a list of domains of activity and participation. As an individual’s functioning and disability involves a context, the ICF includes a list of environmental factors and the concept of personal factors in its framework. The ICF is part of the “Family of International Classifications” (FIC) and meets the standards for health related classifications as defined by the WHO. Although the ICD has a dominating role in health care data management, the WHO aims to reach the same level with the ICF, a classification that is able to define functional status, irrespective of the underlying health condition. Finally, there is a need to enrich daily practice in primary care with more "policy evidence", which entails efficiency and equity. The achievement of individual treatment benefits is in itself not the final argument for promotion of that treatment for all patients. In one of her last editorials "The hidden inequity in health care", Barbara Starfield re-iterates that organ systems based medicine is becoming dysfunctional, because most illness nowadays is multi-morbidity – cutting across diseases and types of diseases and organ systems. The information on health problems is collected disease by disease. Doing so masks the greater needs of people in different population subgroups, because they are more vulnerable to and suffer more different types of illness and combinations of illness. Disease-oriented medicine, whether through guidelines, or through a focus on particular chronic diseases and their management is thus highly inequitable as it cannot address the adequacy of interventions when people have many problems. Diseases are not unique entities; there are greater differences in resource needs within disease categories than across them. We need guidelines that are appropriate to person-focused care, not 6 disease-focused care21. Therefore, health systems should be assessed in relation to their capacity to deal with multi-morbidity in an equitable way27. Looking back at the future. The development of care, especially when it comes to multi-morbidity, illustrates the principle, that, in history we often experience that "circles are closing". In the second half of the 20th century, medicine became more and more orientated towards bio-medical approaches, looking for the molecular causes of diseases. Health care delivery became increasingly fragmented, with the creation of specialties, and left the general practitioner, with a lot of uncertainty. Especially in countries where there was no clear position for the GP in the health system (e.g. no gate-keeping) GPs were facing a continuous erosion of their task and function. In the seventies, the fragmented approach was side-lined by a comprehensive bio-psycho-social model, refocusing on the needs and expectations of patients. GPs became champions in " patient centred communication and consultation"28. An increasing focus on psycho-social problems detached the GP from the "hard core" of medicine: caring for "real diseases". In the nineties, Evidence Based Medicine and clinical epidemiology brought general practitioners back to the debate on how to diagnose and treat diseases. General practitioners and public health experts were in the forefront of the development of critical appraisal of the results of clinical trials. GPs started to develop guidelines, but had to rely on the available evidence, which was disease-oriented excluding comorbidity, a key-feature of general practice. Clinical trials conceived in general practice, starting from how patients presented in clinical practice and defined by clinical symptoms instead of confirmed disease labels, helped to understand the complexity and opened up new methods and arenas for research. The contradictions that arise when implementing disease-specific guidelines for multi-morbidity patients, bring us back to a need for integration at the patient level, and include the re-birth of person- and people centred care, looking at the goals of the patient and combining medical and contextual evidence. In order for GPs to make this happen, there will be a need for a "modern medical generalism" that enables GPs to guide patients through complexity29. The recent reports of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health and the World Health Report 2008: "Primary health care: now more than ever!" helped GPs to put their contribution to health care into the broader interdisciplinary and intersectoral context, addressing the social determinants of health through interdisciplinary cooperation within primary care teams. At the same time, it is interesting to discover how fundamental research on the "mechanisms of disease" reveals a unity of concepts: there are common pathophysiological mechanisms to different chronic diseases (e.g. genetic concepts, inflammatory reactions of immune-ageing, chronic systemic inflammation). So, on the one hand, the "unity of fundamental concepts" and on the other hand the "unity of the integrated approach to the patient" brings us back to an era of integration, comprehensiveness and synthesis. The circles are closing… 7 Multi-morbidity, goal-oriented care and equity. When implementing Goal Oriented Care, there may be a threat to equity, as the way goals are formulated by patients might be determined by e.g. social class. Moreover, integrating "Contextual Evidence", implies the risk of taking the context for granted: people living in poverty will generally have been obliged to take on lower expectations in terms of quantity and quality of life than well-educated people. So, "goal-oriented medical care" could contribute to an increase in social inequities in health. This challenges primary health care providers with the question of how to deal with an "unhealthy" and "inequitable" context. It is obvious that this cannot be the responsibility only of primary care providers. They may have an important "signalling"-role in order to document and draw attention to the problems that patients are facing. This is where Community Oriented Primary Care (COPC) comes into the picture. COPC integrates individual and population-based care, blending clinical skills of practitioners with epidemiology, preventive medicine, and health promotion30. Starting from observations in daily patient care, Community Oriented Primary Care makes a systematic assessment of health-care needs in practice populations, identifies community health problems, implements systematic interventions, involving a target population (e.g. modification of practice procedures, improvement of living conditions) and monitoring the effect of changes to ensure that health services are improved and congruent with the needs of individual patients and of the community. COPC designs specific interventions to address priority health problems. Teams consisting of primary health care workers and community members assess resources and develop strategic plans to deal with problems that have been identified. So, Community Oriented Primary Care is an essential part of a strategy to re-orientate care towards the needs and the goals of the individual and of the community. It will help to identify the "upstream causes" that lead to social inequities in health31. Both communication and education methodologies need to be reviewed with that perspective. Including policy evidence will have important implications for research design and will bring ethics on board, not only at the micro-level, but also at the meso- and macro-level. At the micro-level doctors could be caught in a conflict between their obligation to promote health and their respect for the patients' autonomy32. At the macro-level we will have to investigate how "goal oriented care" may be reconciled with equitable resource allocation in more general terms. In this context Maynard presented the situations of two treatment options – option A, leading to 5 years of good quality-of-life-survival or healthy years of life (HY), and option B, leading to 10 HY33. An obvious evidence-based choice would be option B. However, when limited resources are taken into account, and option B is the most expensive option, at the level of the population, option A might produce more years of good quality of life. So, from a population perspective, the evidence-based choice would be option A instead of B. In this context, a clinician prescribing option B uses resources inefficiently, and deprives other patients of care from which they could benefit. All these ethical issues will have to be discussed in the framework of "Goal Oriented Care" e.g. in patients with multimorbidity. So once more, this will need a degree of congruence between the macro-level in the framework of the political debate on "choices in health care" and the micro-level in the clinical encounter with patients, when discussing how to achieve the goals that they have formulated. Finally, health is global, so more and more within a globalised context, we will need to look at health care on the global scale34. 8 Conclusion Approaching a patient with multi-morbidity challenges both practitioners and researchers. It challenges institutions for health professionals' education to train providers that are not only "experts", or excellent "professionals", but that are also "change agents"35 that continuously improve the health system and question the reality of knowledge and care, as did James Mackenzie. It requires fundamental reflection on the individual provider-patient interaction, on the need for a paradigm-shift from problem-oriented to goal-oriented care, on the organisation of the health care services and the features of the health system. Most fundamentally, it will also require dialogue and communication methodologies between the health sector and persons in need of health care and with other stakeholders within society involved in healthcare at the practice-, research- and policy-level, in order to guarantee the essential characteristics of an effective health system: relevance, equity, quality, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, people-centeredness and innovation. London, 18 November 2011 Acknowledgement. We thank Iona Heath for suggestions to improve the text. 1 WHO. Mortality and burden of disease estimates for WHO Member States in 2008. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2010. 2 Anderson G, Horvath J. Chronic conditions: making the case for ongoing care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, 2002. 3 Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, Holguin F. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;32:962-9. 4 Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R et al, for The Lancet NCD Action Group and the NCD Alliance. Priority actions for the non-communicable diseases crisis. Lancet 2011; 377: 1438–47. 5 Braithwaite RS, Justice AC, Chang CC et al. Estimating the proportion of patients infected with HIV who will die of comorbid diseases. Am J Med 2005; 118 : 890-898 6 Friss-Moller N, Sabin CA, Weber R et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003 ; 348: 1993-2003. 7 Aging with HIV : a cross sectional study of comorbidity prevalence and clinical characteristics across decades of life. JANAC 2011; 22 : 17-25 8 Crothers K, Butt AA, Gibert CL et al. Increased COPD among HIV positive compared to HIV negative veterans. Chest 2006; 130: 1326-1333 9 9 Gillam S, Siriwardena N. The quality and outcomes framework. QOF-transforming general practice. Oxford: Radcliffe, 2011. 10 Norbury M, Fawkes N, Guthrie B. Impact of the GP contract on inequalities associated with influenza immunisation: a retrospective population-database analysis. British Journal of General Practice 2011; DOI:10.3399/bjgp11x583146. 11 Boeckxstaens P, De Smedt D, De Maeseneer J, Annemans L, Willems S. The equity dimension in the Quality and Outcomes Framework. A systematic Review. BMC Health Services Research 2011 : 31; &1: 209. 12 Heath I, Rubinstein A, van Driel ML et al. Quality in primary health care: a multidimensional approach to complexity. BMJ 2009;338:911-3. 13 Wagner EH. Chronic disease management. What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract 1998;1:2-4 14 Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases. JAMA 2005;294:716-24. 15 Mold JW, Blake GH, Becker LA. Goal-oriented medical care. Fam Med 1991;23(1):46-51. 16 Rijken M, Bekkema N. Chronic Disease Management Matrix 2010: Results of a survey in ten European countries. Utrecht, NIVEL: Netherlands institute for health services research, 2011. ISBN 978-94-6122-093-6. 17 Walsh J, Warren KS. Selective Primary health care: an interim strategy for disease control in developing countries. Social Science and Medicine 1980;14:145-63. 18 Barreto ML, Teixeira MG, Bastos FI, Ximenes RAA, Barata RB, Rodrigues LC. Successes and failures in the control of infectious diseases in Brazil: social and environmental context, policies, interventions, and research needs. Lancet 2011; 377: 1877–89. 19 De Maeseneer J, van Weel C, Egilman D, et al. Funding for primary health care in developing countries: money from disease specific projects could be used to strengthen primary care. BMJ 2008; 336: 518–19. 20 De Maeseneer J, Roberts R, Demarzo M et al. Tackling NCDs: a different approach is needed. The Lancet, 2011;378: DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61135-5. 21 Starfield B. The hidden inequity in health care. Int Journal for Equity in Health 2011; 10: 15. 22 De Maeseneer JM, van Driel ML, Green LA, van Weel C. The need for research in primary care. Lancet 2003;362:1314-9. 23 Bodenheimer T. Uneasy alliance: clinical investigators and the pharmaceutical industry. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1539-44. 24 Wallston BS, Wallston KA, Kaplan GD, Maides SA. Development and validation of the Health Locus of Control (HLC) Scale. J. Consult Clin Psychol 1976;44:580-5. 25 Heath I, Rubinstein A, Stange KC, van Driel ML. Quality in primary health care: a multidimensional approach to complexity. BMJ 2009;338:911-3. 10 26 World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. 27 Swanson RC, Mosley H, Sanders D et al. Call for global health-systems impact assessments. The Lancet 374;2009:433-435. 28 Pendleton DA. Doctor patient communication. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford, 1981. 29 Anonymous. Guiding patients through complexity: modern medical generalism. London, Report of an independent commission for the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Health Foundation; October 2011. 30 Rhyne R, Bogue R, Kukulka G, Fulmer N. Community-oriented primary care: Health care for the 21st century. Washington, DC: Am Assoc Public Health, 1998. 31 De Maeseneer J,Willems S, De Sutter A, Van De Geuchte ML, Billings. Primary health care as a strategy to achieve equitable care: a literature review commissioned by the Health Systems Knowledge Network. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/primary_health_care_2007_en.pdf 32 Bremberg S, Milstun T. Parients' autonomy and medical benefit: ethical reasoning among GPs. Fam Pract 2000;14:124-8. 33 Maynard A. Evidence based medicine: an incomplete method for informing treatment choices. Lancet 1997;349:126-8. 34 De Maeseneer J, van Weel C, Roberts R. Family medicine's commitment to MDGs. Lancet 2010;375:1588-9. 35 Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta Z A, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet 2010;376:1923-58. 11