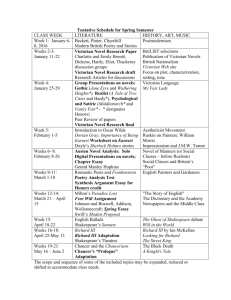

The Canterbury Tales * Introduction

advertisement

Victorian Literature – An Overview VICTORIAN LITERATURE is the literature produced during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901) and corresponds to the Victorian era. It forms a link and transition between the writers of the Romantic period and the very different literature of the 20th century. The 19th century saw the novel become the leading form of literature in English. The works by preVictorian writers such as Jane Austen and Walter Scott had perfected both closely-observed social satire and adventure stories. Popular works opened a market for the novel amongst a reading public. The 19th century is often regarded as a high point in British literature as well as in other countries such as France, the United States, and Russia. Books, and novels in particular, became ubiquitous, and the “Victorian novelist” created legacy works with continuing appeal. Queen Victoria Charles Dickens arguably exemplifies the Victorian novelist better than any other writer. Extraordinarily popular in his day with his characters taking on a life of their own beyond the page, Dickens is still the most popular and most read author of the time. His first real novel, The Pickwick Papers, written at age twenty-five, was an overnight success, and all his subsequent works sold extremely well. He was in effect a self-made man who worked diligently and prolifically to produce exactly what the public wanted; often reacting to the public taste and changing the plot direction of his stories between monthly numbers. The comedy of his first novel has a satirical edge which pervades his writings. These deal with the plight of the poor and oppressed and end with a ghost story cut short by his death. The slow trend in his fiction towards darker themes is mirrored in much of the writing of the century, and literature after his death in 1870 is notably different from that at the start of the era. William Thackeray was Dickens’ great rival at the time. With a similar style but a slightly more detached and barbed satirical view of his characters, he also tended to depict situations of a more middle class flavor than Dickens. He is best known for his novel Vanity Fair, subtitled A Novel without a Hero, which is also an example of a form popular in Victorian literature: the historical novel, in which very recent history is depicted. Anthony Trollope tended to write about a slightly different part of the structure, namely the landowning and professional classes. Away from the big cities and the literary society, Haworth in West Yorkshire held a powerhouse of novel writing: the home of the Brontë family. Anne, Charlotte and Emily Brontë had time in their short lives to produce masterpieces of fiction although these were not immediately appreciated by Victorian critics. Wuthering Heights, Emily’s only work, in particular has violence, passion, the supernatural, heightened emotion and emotional distance, an unusual mix for any novel but particularly at this time. It is a prime example of Gothic Romanticism from a woman’s point of view during this period of time, examining class, myth, and gender. Another important writer of the period was George Eliot, a pseudonym which concealed a woman, Mary Ann Evans, who wished to write novels which would be taken seriously rather than the romances which women of the time were supposed to write. The style of the Victorian novel Virginia Woolf in her series of essays The Common Reader called George Eliot's Middlemarch “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people.” This criticism, although rather broadly covering as it does all English literature, is rather a fair comment on much of the fiction of the Victorian Era. Influenced as they were by the large sprawling novels of sensibility of the preceding age they tended to be idealized Intro to Victorian Literature 1 portraits of difficult lives in which hard work, perseverance, love and luck win out in the end; virtue would be rewarded and wrong-doers are suitably punished. They tended to be of an improving nature with a central moral lesson at heart, informing the reader how to be a good Victorian. This formula was the basis for much of earlier Victorian fiction but as the century progressed the plot thickened. Charles Dickens Eliot in particular strove for realism in her fiction and tried to banish the picturesque (focusing on scenic pleasure) and the burlesque (parody and grotesque exaggeration) from her work. Another woman writer Elizabeth Gaskell wrote even grimmer, grittier books about the poor in the north of England, but even these usually had happy endings. After the death of Dickens in 1870 happy endings became less common. Such a major literary figure as Charles Dickens tended to dictate the direction of all literature of the era, not least because he edited All the Year Round, a literary journal of the time. His fondness for a happy ending with all the loose ends neatly tied up is clear and although he is well known for writing about the lives of the poor, they are sentimentalized portraits, made acceptable for people of character to read; to be shocked but not disgusted. The more unpleasant underworld of Victorian city life was revealed by Henry Mayhew in his articles and book London Labour and the London Poor. This change in style in Victorian fiction was slow coming but clear by the end of the century, with the books in the 1880s and 90s more realistic and often grimmer. Even writers of the high Victorian age were censured for their plots attacking the conventions of the day with Adam Bede being called “the vile outpourings of a lewd woman’s mind” and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall “utterly unfit to be put into the hands of girls.” The disgust of the reading audience perhaps reached a peak with Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure which was reportedly burnt by an outraged bishop of Wakefield. The cause of such fury was Hardy’s frank treatment of religion and his disregard for the subject of marriage; a subject close to the Victorians’ heart, with the prevailing plot of the Victorian novel sometimes being described as a search for a correct marriage. Hardy had started his career as seemingly a rather safe novelist writing bucolic scenes of rural life, but his disaffection with some of the institutions of Victorian Britain was present as well as an underlying sorrow for the changing nature of the English countryside. The hostile reception to Jude in 1895 meant that it was his last novel, but he continued writing poetry into the mid 1920’s. Other authors such as Samuel Butler and George Gissing confronted their antipathies to certain aspects of marriage, religion or Victorian morality and peppered their fiction with controversial anti-heros. Butler's Erewhon, for one, is a utopian novel satirizing many aspects of Victorian society with Butler’s particular dislike of the religious hypocrisy attracting scorn and being depicted as “Musical Banks.” The Victorians are sometimes credited with “inventing childhood,” partly via their efforts to stop child labor and the introduction of compulsory education. As children began to be able to read, literature for young people became a growth industry, with not only established writers producing works for children (such as Dickens' A Child's History of England) but also a new group of dedicated children’s authors. Writers like Lewis Carroll, R. M. Ballantyne and Anna Sewell wrote mainly for children, although they had an adult following. Other authors such as Anthony Hope and Robert Louis Stevenson wrote mainly for adults, but their adventure novels are now generally classified as for children. Other genres include nonsense verse, poetry which required a child-like interest (e.g. Edward Lear). School stories flourished: Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown's Schooldays and Rudyard Kipling's Stalky and Co. are classics. Intro to Victorian Literature 2 The Victorian Bildungsroman Generally speaking Great Expectations, like Jane Eyre, fits the Victorian version of the bildungsroman, a term adopted from the genre of novel that arose during the German Enlightenment. It generally has many of the following characteristics The protagonist grows from child to adult. The protagonist must have a reason to embark upon his or her journey. A loss or discontent must, at an early stage, jar him or her away from their home or family setting. The process of maturation is long, arduous and gradual, involving repeated clashes between the hero’s needs and desires and the views and judgments enforced by an unbending social order. Eventually, the spirit and values of the social order become manifest in the protagonist, who is ultimately incorporated into the society. The novel ends with the protagonist’s assessment of himself and his new place in that society. The Victorian Subgenres Great Expectations is possibly the greatest of all Dickens’ novels, not the least because it contains important elements of a number of Victorian subgenres.. The thirteenth of his novels, it is one of three relatively short novels designed for weekly magazine serialization rather than monthly “part” publication, the other two being Hard Times (1854) for Household Words and A Tale of Two Cities (1859), the first novel serialized in All the Year Round. It is also his third major work to employ the first-person narrative point of view, the other two being the quasi-autobiographical David Copperfield (1849) and (at least, in part) Bleak House (1852). Though the modern reader may see this novel as a retrospective, first-person confessional, Great Expectations can be classified in terms of the various subgenres of the Victorian novel; for, unlike his earlier attempt at pseudo-autobiography, David Copperfield, Great Expectations does not fit perfectly into the Bildungsroman – like Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. Great Expectations contains elements of all of the following Victorian “subgenres”: Social Satire To counter the lack of humor in A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens set out to provide character comedy, situation comedy, and especially social satire. Dickens makes us laugh at a society that values wealth and class, that condones snobbery and social injustice, that transports felons for relatively minor crimes, and that has allowed a great national institution, the theatre, to deteriorate. Although the utterances and actions of many of the characters make us laugh, each character evokes a different kind or quality of laughter. The Novel of Crime and Detection A relatively new form, the Novel of Crime and Detection (sometimes mislabeled “The Murder Mystery”) has influenced the characterization and the plot of Great Expectations. Like many of Wilkie Collins's novels, Great Expectations introduces us to figures from the criminal underworld, in this case a lawyer and his nefarious clients, in particular, the escaped convict Abel Magwitch, the swindler Compeyson, and the murderess Molly Magwitch. The reader must puzzle out what the relationship of such characters is to Miss Havisham, and if her eccentricity about Satis House’s clocks and her wedding dress is somehow associated with them in the past. Silver Fork Novel The Silver Fork Novel, popular in the 1820’s and 1830’s, was at once escapist in describing former elegance and glitter, and censorious in judging the frivolities and often supercilious emphasis on the Intro to Victorian Literature 3 aesthetic (rather than on the moral) that characterized aristocratic high society. Charles Lever's A Day's Ride, which began in All the Year Round in July, 1860, concerns a class and a lifestyle that Dickens personally held in contempt but that fascinated many of his readers. We may, at one level, regard Great Expectation sas an “Anti-Silver Fork” novel, a satire upon the pretentiousness and money morality of the aristocracy, as represented by the brewery heiress Miss Havisham, her grasping relatives the Pockets, and the fatuous Uncle Pumblechook. Indeed, the very title of the novel may be meant ironically because the collapse of Pip’s great expectations leaves him with no alternative but the bourgeois course of working for a living. Newgate Novel A form of fiction pioneered by Thackeray in Catherine, Ainsworth in Rookwood, and especially by Dickens himself in Oliver Twist (1837), this subgenre involves underworld types such as the fence (receiver of stolen goods), the pickpocket, the criminal mastermind, the highwayman, the housebreaker, the prostitute, the murderer, and the thief-taker (informer). This aspect of Great Expectations is embodied in the relationship between Magwitch and Compeyson, and in the plot gambit regarding the fate of Magwitch should the authorities discover that he has returned to England. This aspect is reinforced by references to George Lillo’s George Barnwell in The London Merchant and Pip’s feelings of guilt and betrayal, ironically stemming from his theft of the brandy, the pie, and the file to aid Magwitch (who rewards Pip for what he misinterprets as compassion rather than his actual motivation: fear). The Gothic Novel The tradition of the novel of suspense, horror, fear, and superstition that began with Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), continued into the nineteenth-century with the novels of Anne Radcliffe (notably, The Mysteries of Udolpho), Sir Walter Scott's The Bride of Lammermoor, Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey (a satire on the form), and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. The melancholy ruin of Satis House, the bride frozen in time, the domineering aristocrat Bentley Drummle, the child (young Pip) and the young woman in distress, the monster (Orlick), and the suspenseful entrapments of Pip and Magwitch are all Gothic aspects of Great Expectations. Serial Fiction Each installment both advances the action, resolves previous problems, and poses fresh difficulties for the protagonist. Each part must be coherent and complete in itself, yet make connections (through continuing, easily recognized characters and settings) to what has gone before. Customarily, each part will end at a moment of crisis (for example, Pip's running off to the marshes to deliver the food and file to the convict at the end of part one) which the next will resolve--these complementary closings and openings are termed “curtains.” Romance An older form than the novel, this genre continued into the nineteenth century with Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Romance subordinates realism to emotion, and offers intensely personal Intro to Victorian Literature 4 rather than rational or objective responses. Pip’s hopeless obsession with Estella ripples all the way through Great Expectations, and is in fact his chief motivation for becoming a “gentleman.” The fairy-tale patterns derived from “Hansel and Gretel” and “Cinderella” contribute to the novel as romance. Novel-with-a-Purpose (Political Novel) Many of the novels of Wilkie Collins, Dickens's protégé, fall under this heading since they advocate legal and social change--his Heart and Science, for example, attacks animal vivisection. Since Dickens described himself as “first and last, a reformer,” Great Expectations' exposing the need for penal and educational reforms is consistent with this subgenre and Dickens’s agenda throughout his works. His higher “purpose” is connected with the simple question, “What is a gentleman?” If we read the text properly, humble Joe Gargery rather than arrogant Bentley Drummle and his frivolous Finches of the Grove should be our answer. Historical Novel Although the pattern of a story's originating in the past and moving forward to the year of publication is not uncommon in Victorian fiction, Great Expectations begins just after the Napoleonic Wars and proceeds to recount events in detail until approximately 1830-35 before jumping ahead eleven years (1840-5, the major period of England's railway construction) to close the story. Dickens carefully implants details in the text of the narrative to suggest that events therein described are very much “of the past.” For example, since the one-pound notes mentioned in Ch. 10 were out of circulation from 1826 until 1915, the story must open prior to 1826. Since the death sentence which hangs over Magwitch as a transported felon was eliminated in 1835, and since the very end of the story transpires eleven years after Magwitch's death, Dickens concludes the story no later than 1846. The paddle-wheeler, a species of which mortally wounds Magwitch, was supplanted by the screw-propeller in 1839, thereby reinforcing a terminal date sometime in the mid-1840s. The gibbet specifically noted at the opening reflects the practice abandoned in 1832 of leaving condemned criminals to rot where they were hanged. The king specifically mentioned at the beginning of the novel is George III, who died in 1820, when Pip was seven or eight. Thus, Dickens, born in 1812, seems to be identifying himself with his protagonist. The guinea, mentioned in Ch. 13, went out of circulation in 1817, yet young Charles Dickens arrived in London by coach from Chatham, the marsh country of the tale, at the age of ten (1822). Pip is about 23 in the middle of the book, and about 34 at the end; since Dickens turned 34 in February, 1846, he seems to be inviting his readers to connect the author and the narrator. Charles Dickens – Biographical Sketch Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812, the son of John and Elizabeth Dickens. John Dickens was a clerk in the Naval Pay Office. He had a poor head for finances, and in 1824 found himself imprisoned for debt. His wife and children, with the exception of Charles, who was put to work at Warren’s Blacking Factory, joined him in the Marshalsea Prison. When the family finances were put at least partly to rights and his father was released, the 12-year-old Dickens, already scarred psychologically by the experience, was further wounded by his mother’s insistence that he continue to work at the factory. His father, however, rescued him from that fate, and between 1824 and 1827 Dickens was a day pupil at a school in London. At fifteen, he found employment as an office boy at an attorney’s office, while he studied shorthand at night. His brief stint at the Blacking Factory haunted him all of his life — he spoke of it only to his wife and to his closest friend, John Forster — but the dark secret became a source both of creative energy and of the preoccupation with the themes of alienation and betrayal which would emerge, most notably, in David Copperfield and in Great Expectations. Intro to Victorian Literature 5 In 1829 he became a freelance reporter at Doctor’s Commons Courts. By 1832 he had become a very successful shorthand reporter of Parliamentary debates in the House of Commons, and began work as a reporter for a newspaper. In 1833 his first published story appeared, and was followed, very shortly thereafter, by a number of other stories and sketches. In 1834, still a newspaper reporter, he adopted the soon to be famous pseudonym “Boz.” His impecunious father (who was the original of Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield, as Dickens’s mother was the original for the querulous Mrs. Nickleby) was once again arrested for debt, and Charles, much to his chagrin, was forced to come to his aid. Later in his life both of his parents (and his brothers) were frequently after him for money. In 1835 he met and became engaged to Catherine Hogarth. The first series of Sketches by Boz was published in 1836, and that same year Dickens was hired to write short texts to accompany a series of humorous sporting illustrations by Robert Seymour, a popular artist. Seymour committed suicide after the second number, however, and under these peculiar circumstances Dickens altered the initial conception of The Pickwick Papers , which became a novel. The Pickwick Papers continued in monthly parts through November 1837, and, to everyone’s surprise, it became an enormous popular success. Dickens proceeded to marry Catherine Hogarth on April 2, 1836, and during the same year he became editor of Bentley’s Miscellany, published (in December) the second series of Sketches by Boz, and met John Forster, who would become his closest friend and confidant as well as his first biographer. After the success of Pickwick, Dickens embarked on a full-time career as a novelist, producing work of increasing complexity at an incredible rate, although he continued, as well, his journalistic and editorial activities. Oliver Twist was begun in 1837, and continued in monthly parts until April 1839. It was in 1837, too, that Catherine’s younger sister Mary, whom Dickens idolized, died. She too would appear, in various guises, in Dickens’s later fiction. A son, Charles, the first of ten children, was born in the same year. Nicholas Nickleby got underway in 1838, and continued through October 1839, in which year Dickens resigned as editor of Bentley's Miscellany. The first number of Master Humphrey's Clock appeared in 1840, and The Old Curiosity Shop, begun in Master Humphrey, continued through February 1841, when Dickens commenced Barnaby Rudge, which continued through November of that year. In 1842 he embarked on a visit to Canada and the United States in which he advocated international copyright (unscrupulous American publishers, in particular, were pirating his works) and the abolition of slavery. His American Notes, which created a furor in America (he commented unfavorably, for one thing, on the apparently universal — and, so far as Dickens was concerned, highly distasteful — American predilection for chewing tobacco and spitting the juice), appeared in October of that year. Martin Chuzzlewit, part of which was set in a not very flatteringly portrayed America, was begun in 1843, and ran through July 1844. A Christmas Carol, the first of Dickens's enormously successful Christmas books — each, though they grew progressively darker, intended as “a whimsical sort of masque intended to awaken loving and forbearing thoughts” — appeared in December 1844. In 1848 Dickens also wrote an autobiographical fragment, directed and acted in a number of amateur theatricals, and published what would be his last Christmas book, The Haunted Man, in December. 1849 saw the birth of David Copperfield, which would run through November 1850. In that year, too, Dickens founded and installed himself as editor of the weekly Household Words, which would be succeeded, in 1859, by All the Year Round, which he edited until his death. 1851 found him at work on Bleak House, which appeared monthly from 1852 until September 1853. Intro to Victorian Literature 6 By 1860, the Dickens family had taken up residence at Gad's Hill. Dickens, during a period of retrospection, burned many personal letters, and re-read his own David Copperfield, the most autobiographical of his novels, before beginning Great Expectations, which appeared weekly until August, 1861. During 1869, his readings continued, in England, Scotland, and Ireland, until at last he collapsed, showing symptoms of mild stroke. Further provincial readings were cancelled, but he began upon The Mystery of Edwin Drood.. Dickens's final public readings took place in London in 1870. He suffered another stroke on June 8 at Gad's Hill, after a full day's work on Edwin Drood, and died the next day. He was buried at Westminster Abbey on June 14, and the last episode of the unfinished Mystery of Edwin Drood appeared in September. Emily Brontë – Biographical Sketch Emily Brontë was born at her father’s parsonage at Thornton in the parish of Bradford in 1818. She was the fifth child in a family whose eldest was only four years and three months old. Close as they were in ages, it proved a happy thing for Emily when yet another sister, Anne, was born in 1820, for Anne became her lifelong confidante and friend. Of all the influences on Emily’s life, the landscape of the home at Haworth had the greatest effect in quickening her mind and in shaping her character. Of human influences, there can be no doubt, her father was the most lasting; a countryman born with a keen love of nature, he eagerly opened her eyes to the natural world lying at her door. Echoes of the little moorland birds, of the invisible larks, of the linnets chattering in the eaves of the houses, are a feature of that region; Emily grew up on the sound. While material prosperity was never the prime consideration of their home it is not true to say that the children lacked the things that mattered to their happiness. They had love; they had security; they had toys, marionettes, ninepins, bricks; they had successive boxes of soldiers which in time fired their imagination to become adventurers, epic writers, chroniclers; above all, they had books, as they grew. Reading came to them like an epidemic; as soon as one could read they were all infected. Mr. Bronte had been happy indeed in marrying an intrepid young woman with high ideals who regarded poverty as a positive advantage in the pursuit of perfection. Her courage was, unfortunately, not equaled by her health, and within eighteen months of the family settling at Haworth she died of cancer, at age 38. Mr. Bronte at the age of 44 was left without a wife, to his lasting misery and increasing oddity, and the children were subjected to the authoritarian rule of a maiden aunt. She was their mother’s elder sister, Miss Elizabeth Barnwell, who came north from Penzance to keep house for her brother-in-law and bring up his children. Two of Emily’s sisters died of tuberculosis within the next few years. From 1825 to 1831 the remaining Brontës – Papa, Charlotte, Branwell, Emily, Anne – and their aunt Miss Branwell, lived together in Haworth Parsonage. These six years when they were all at home together were an extremely important formative period in the young Brontë’s lives. They roamed in the moors. They cherished pets. But the important point is that during these six years they began to create, to invent, and to write their inventions down in fictitious forms. In 1837 Emily took a post as governess in a girls’ boarding school of forty pupils, known as Law Hill, on one of the many Pennine hills surrounding the town of Halifan. The most interesting feature of her Intro to Victorian Literature 7 stay is that Law Hill is not far from High Sunderland and Shibeden Hall, two fine old houses that served as the inspiration for Wuthering Heights and Thrushcroft Grange. Charlotte held her job for three years. In the may of 1830 Charlotte left the school. Her health and spirits had utterly failed her, and the doctor consulted and advised her that if she values her life, she must return home. She did so, and was slowly restored to tranquility. She was twenty-two. In 1845 the young Brontës were all at home together, living in domestic misery and regarding themselves as failures. Then an event occurred which changed the course of their lives and added riches to English literature: Emily had been copying her poems into two notebooks, when Charlotte accidentally lighted upon one notebook and read it contents. Honor must always be paid to Charlotte for her instant conviction that these poems were quite out of the ordinary: terse, vigorous, and genuine, with a peculiar music. The Brontes decided to bring out a volume of poems by all three sisters and got them published under the male names of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. After they saw their poetry in print, the three sisters each began to write and finished a novel. Charlotte’s novel was called Jane Eyre, Emily’s novel was called Wuthering Heights and Anne’s novel was called Agnes Grey. They were refused by publisher after publisher until Smith Elder and Company, accepted Jane Eyre. Not long after that Wuthering Heights was published, followed by Anne’s Agnes Gray. Though the reviews of Jane Eyre were not particularly good, readers liked it and it became a best seller. Curiously readers believed that all three novels were written by the same person – Curer Bell, the pen name for Charlotte. Introduction to Wuthering Heights Wuthering Heights was published in 1847 under the pseudonym of Ellis Bell. Emily Bronte probably began writing this novel towards the end of 1845, though it is possible that she may have conceived the story earlier. The early reviews of this novel were a mixture of approval and disapproval. More than one commentator expressed in the same breath his condemnation of the subject matter of Wuthering Heights and his recognition of its originality and genius. Wuthering Heights is the story of two families and an outsider. The two families are the Earnshaw family living at a place called Wuthering Heights, and the Linton family residing at a place called Thrushcross Grange, which is situated, in the Valley at a distance of about four miles from Wuthering Heights which is situated on a hill. Moors and hills separate the two abodes from each other. At a small distance from Thrushcross Grange lies the village of Gimmerton with its church. The story covers almost three generations. Mr. and Mrs. Earnshaw, living at Wuthering Heights, have two children, Hindley and Catherine. Mr. and Mrs. Linton, living at Thrushcross Grange, have likewise two children, Edgar and Isabella. Subsequently, after their respective marriages, Hindley Earnshaw begets a son who is named Hareton while Cathy gives birth to a girl who is also named Catherine. Isabella, the daughter of the Lintons marries Heathcliff, an outsider who came to live with the Earnshaws when he was a boy. Of this marriage is born a son who gets the name Linton. Towards the close of the novel, Hareton and the younger Catherine are preparing to get married. It is in this way that he novel deals with three generations. The novel is dominated by the figure of Heathcliff. His personality and actions constitute the real substance of the book. Heathcliff dominates the plot like a colossus, and he largely determines the course of the story. Though not a traditional protagonist, Heathcliff is the central character of the novel. Around him, the story revolves, and he imparts to the book its real interest. If we take away Heathcliff from the novel, the story falls to pieces. The leading theme of Wuthering Heights may be stated as Heathcliff’s love for Cathy and the revenge he takes upon various persons, the revenge being prompted by the frustration of his love and by the social contempt heaped upon him by Hindley Earnshaw and Edgar Linton. Intro to Victorian Literature 8