The Treatment of Offenders and the Challenge of Mass Incarceration

advertisement

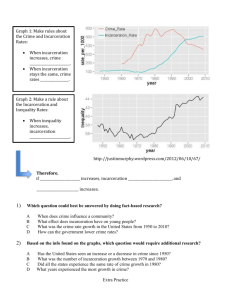

The Treatment of Offenders and the Challenge of Mass Incarceration Reflections Offered to His Holiness Pope Francis *** The Honorable Phillip Rapoza President of the International Penal and Penitentiary Foundation Your Holiness, It is both an honor and a privilege to come before you and to share some reflections that I offer as President of the International Penal and Penitentiary Foundation. The IPPF is headquartered in Switzerland and promotes studies in the fields of crime prevention and the treatment of offenders and it is with that focus that I offer the following remarks. Before proceeding further, however, I would like to thank Your Holiness most sincerely for the opportunity to come before you today and to do so together with representatives of organizations whose work is allied to that of the IPPF. With your permission, Holy Father, I would like to begin by quoting from your letter to the participants in the 19th International Congress of the International Association of Penal Law and of the 3rd Congress of the Latin-American Association of Penal Law and Criminology. In that communication you stated that the “great challenge…we all must face together” is to promote “a humanizing, genuinely reconciling justice, a justice that leads the criminal…to rehabilitation and reintegration into the community.” Your words, Holy Father, could not have been more timely. The rehabilitation of offenders and their reintegration into society is a pressing need that faces many challenges, one of which I would like to address today. We live in a world in which high rates of imprisonment have resulted in the mass incarceration of millions. More than 10 million people worldwide are in prison and the number continues to increase. Indeed, during the last 15 years, the world’s prison population has grown at a rate almost 10 percent faster than the world’s entire population. Approximately one quarter of the world’s inmates are imprisoned in the United States, where the prison population has quadrupled to 2.4 million during the last 40 years. This is not, however, a uniquely American problem. The prison population in England and Wales has more than doubled in the past 20 years, as the average prison sentence imposed and the amount of time served have both increased. Similarly, considerable increases have occurred in Latin America, where prison populations have more than quadrupled in El Salvador, tripled in Brazil and doubled in Mexico. It should be noted, however, that although not every country contributes to the problem of mass incarceration, a significant number do. Higher rates of incarceration not only increase the number of persons in prison, but also intensify the problem of prison overcrowding. Indeed, approximately 125 countries worldwide have prison systems that are either beyond or nearly beyond capacity. Overcrowded prisons, in turn, are bastions of despair, disease and violence, with increased rates of both suicide and sexual abuse. Such institutions are seriously challenged in their ability to treat inmates in a humane and dignified manner and are often without adequate resources to provide basic educational, vocational, medical and mental health services needed to help rehabilitate and reintegrate offenders. The continued high rate of incarceration has not only affected the treatment of inmates, but also changed the composition of prison populations. Where prisons were once reserved primarily for violent or repeat offenders, they are increasingly populated by low level, nonviolent and first offenders serving longer and longer sentences. Moreover, while prison populations are predominantly male, a noteworthy growth in the rate of female incarceration has taken place. The impact of this escalation in incarceration is increasingly suffered by children, who share the consequences of their parents’ imprisonment, often over the long term. In the United States, for example, approximately 1.5 million children have a parent who is incarcerated. The effects of mass imprisonment fall disproportionately on other groups as well, including the poor. Similarly, disparities are evident in the rate of incarceration for different racial and ethnic groups. By way of example, young African-American and Hispanic males are incarcerated in the U.S. at a rate far exceeding their representation in the population at large, jeopardizing not only their individual futures, but also that of their families and their communities. The mass incarceration of our fellow man reflects a change over time in the philosophy of incarceration from one of reform and rehabilitation to one of incapacitation and punishment. Redefining the theory of incarceration in that way necessarily shifts the focus from repairing the individual to concentrating on his removal from society and punishment for his crime. The prioritization of containment and retribution as the bases for incarceration is not the only cause, however, promoting high rates of imprisonment around the world. Another is the perception that incarceration is the most effective tool for controlling crime and that imprisonment reflects the just deserts an offender should anticipate for his or her actions. Indeed, the idea of getting “tough” on crime drives many criminal justice systems to the increased use of incarceration. This trend also has been advanced by the so-called worldwide “War on Drugs” as well as other practices such as the imposition of harsher sentences and the use of mandatory minimum sentences. In the United States in particular, the use of plea bargaining has resulted in 95 percent of all criminal prosecutions concluding with a sentencing agreement, which often calls for a period of incarceration. Whatever may be the merits of such practices, it remains that two-thirds of all inmates in the U.S. reoffend within three years of their release from prison, often committing more violent and more serious offenses than those for which they were originally incarcerated. This is not to deny, of course, that there exist legitimate considerations of public safety that support the imprisonment of violent and repeat offenders. That said, it is nonetheless appropriate to scrutinize the use of mass incarceration and to determine the most suitable and effective means to ensure that rehabilitation and reintegration remain priorities of our criminal justice policies. Perhaps the most proactive means of addressing mass incarceration is to consider alternatives to imprisonment for nonviolent offenders as well as for those who are drug dependent or mentally ill. The use of alternative sentences, intermediate sanctions and diversion programs can be a productive, not to mention cost-effective, way to treat such individuals and for offenders to serve their sentence. Moreover, suspended sentences that employ services, supervision and monitoring while the offender remains in society provide obvious benefits to the individual, his family and the community of which he or she is a part. Such sentences also can help to avoid the sometimes tragic consequences of incarceration as well as the heavy social burden typically associated with imprisonment. If nothing else, the cost efficiencies of such alternatives as compared to imprisonment constitute a significant benefit. Even in circumstances where a sentence of imprisonment is imposed, there are opportunities to mitigate the current high rate of incarceration. In the case of mandatory sentences, judicial discretion should be restored and draconian sentences for non-violent and low level drug offenses should be eliminated. At the same time more services and opportunities for rehabilitation should be provided inside prison itself. To the extent that incarcerated populations are heavily impacted by both substance abuse and mental health issues, it is also appropriate to question whether prison is the most appropriate setting in which to deal with such medical issues. Incarceration itself does not remedy the underlying problem. At the very least, however, we must consider how to provide such services during the period of incarceration. Finally, obstructions that prevent prisoners from reintegrating into society following incarceration should be removed. For example, in circumstances where the practice of parole has been eliminated it should be restored. In any case, considering that 95 percent of all prisoners are eventually released, they should be better prepared for re-entry into society. Moreover, the transition of an inmate back into the community generally will require the continued use of support services, as least until the individual is self-sustaining. In sum, Your Holiness, the weight of mass incarceration falls disproportionately on the poor, minorities, children, the drug addicted and those suffering from physical and mental illnesses. In many ways such a process creates a society within a society, the social costs of which are considerable. Moreover, conditions of imprisonment often fail to respect basic human rights. The continued high rate of incarceration, although a response to crime, is thus not a solution to it. Indeed, we cannot incarcerate our way out of the problem of crime. As you stated in the letter that I have previously quoted, “measures adopted against evil are not satisfied by restraining, dissuading and isolating the many who have caused it.” You went on to say that we must “help them to reflect, to travel the paths of good, to be authentic persons who, removed from their own hardships, become merciful themselves.” To advance the social and moral rehabilitation of those who have offended, we must respect the human dignity of every person and view each individual as worthy of rehabilitation and reintegration into society. Each of us has that duty toward our fellow man, but as Your Holiness also said, “How wonderful it would be for the necessary steps to be taken so forgiveness does not remain exclusively in the private realm, but instead reaches a truly political and institutional dimension…” I trust, Your Holiness, that it is not unreasonable to look forward to a time when our public policy and institutional practices more clearly reflect such a consensus, especially as it relates to the treatment of offenders who have stumbled but who may yet get up and walk the straight path. I humbly ask, Holy Father, that you continue to strive on their behalf, as will all of us.