case_study_f_the_jordan_river

advertisement

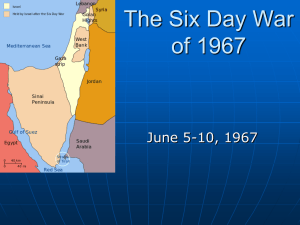

Case Study F: The Jordan River The Jordan River is small by international standards but is of extraordinary importance in the arid Middle East. It originates in the mountains of eastern Lebanon and is fed from rivers in Jordan, Israel, Syria, and Lebanon. The competition for the Jordan’s water is perhaps more intense than any other river in the world. It is especially important to Israel and Jordan, the two countries it divides for most of its southward course. The Jordan is the longest river in Israel and the only river that flows year-round; Israel’s other rivers dry up in the summer and contain contamination. Jordan has three main rivers, but one of them (the Zarqa) is heavily polluted. The lack of alternatives for fresh water makes both Jordan and Israel highly dependent on the Jordan River, and use of the river by one country indicates a decrease in the water available to the other. Jordan and Israel were in perpetual conflict from Israel’s creation in 1947 until 1994. This hostility was principally the result of the claim of both to the same territory: Jordan, along with Palestine, had been under British control until gaining independence in 1947. Like the Arab states surrounding Israel, Jordan was full of refugees from Palestine who believed that their land had been taken unjustly. Israel maintained that its territory was guaranteed by both the British and United Nations. This historical claim, combined with religious animosity, remains the overriding feature of politics in the Middle East. Despite being adversaries, Jordan and Israel have to share the Jordan River. High population increases in both countries (due mainly to immigration in Israel’s case and a high birth rate in Jordan’s case) have placed more pressure on freshwater resources. In the 1950s, Israel built its National Water Carrier, a series of aqueducts, or channels or carrying a large quantity of flowing water, and pumps, to transport water from the Jordan River and the Sea of Galilee to the Negev Desert in the south. The surrounding countries saw this diversion as a symbol of Israel’s expansionist visions, and Syrian military units fired on the construction team in 1955. In the early 1960s, Syria, backed by the other Arab countries, planned to divert the Jordan’s headwaters, the source of the river, into Arab territory, thus diminishing the amount of water available to Israel downstream. Diversion was part of a UN-initiate plan for water development for the whole region, but such plans alarmed Israel and indirectly led to war between Israel and surrounding Arab countries. The “Six-Day War,” also known as the Third Arab-Israeli War, broke out in 1967 amid heightened fears from each side that the other would launch a preemptive attack. Israel won the war emphatically. Among the territory it captured were the Banyas River headwater (this preventing Syria’s planned diversion), the West Bank, the northern bank of the Yarmouk River, and the greater portion of the Jordan River. In the year after the war ended, Israel increased its water use from the Jordan by 33 percent while Jordan lost significant access to the river’s water. The West Bank valley also became a key source of water or Israel dure to its wells and underground water source. Jordan has constructed several canals and dams to maximize its water supply, and Israel has improved the efficiency of its water use through advanced irrigation technology. Nevertheless, both countries face continuing water shortages. By the 1990s they decided that cooperation with each other was better than perpetual conflict. In 1994, they signed a peace treaty that ended the state of war between them and included articles about the Jordan River. Both countries agreed to share the river; to build storage facilities to hold excess water from rain floods; to construct dams to manage river flow; and to protect the river from pollution, contamination, and industrial disposal. This agreement will likely increase the supply of quality fresh water for both countries. While the conflict between Jordan and Israel appears to have subsided, Syria and Lebanon—the other two countries that control tributaries to the Jordan River—remain uncommitted to mutual management of the river.