Résumé: Absolutism

advertisement

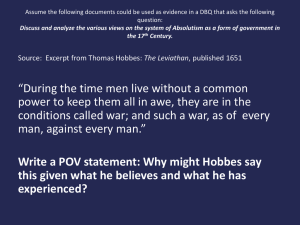

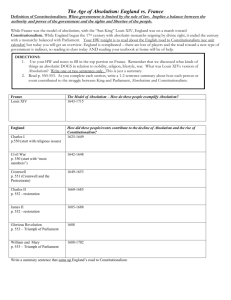

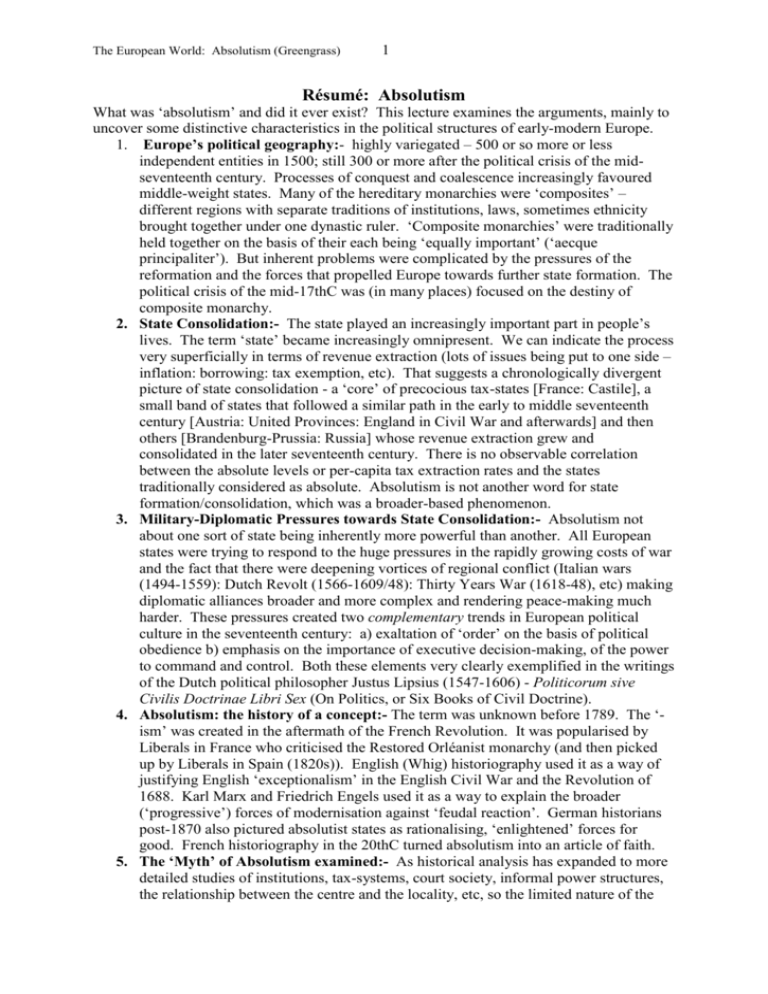

The European World: Absolutism (Greengrass) 1 Résumé: Absolutism What was ‘absolutism’ and did it ever exist? This lecture examines the arguments, mainly to uncover some distinctive characteristics in the political structures of early-modern Europe. 1. Europe’s political geography:- highly variegated – 500 or so more or less independent entities in 1500; still 300 or more after the political crisis of the midseventeenth century. Processes of conquest and coalescence increasingly favoured middle-weight states. Many of the hereditary monarchies were ‘composites’ – different regions with separate traditions of institutions, laws, sometimes ethnicity brought together under one dynastic ruler. ‘Composite monarchies’ were traditionally held together on the basis of their each being ‘equally important’ (‘aecque principaliter’). But inherent problems were complicated by the pressures of the reformation and the forces that propelled Europe towards further state formation. The political crisis of the mid-17thC was (in many places) focused on the destiny of composite monarchy. 2. State Consolidation:- The state played an increasingly important part in people’s lives. The term ‘state’ became increasingly omnipresent. We can indicate the process very superficially in terms of revenue extraction (lots of issues being put to one side – inflation: borrowing: tax exemption, etc). That suggests a chronologically divergent picture of state consolidation - a ‘core’ of precocious tax-states [France: Castile], a small band of states that followed a similar path in the early to middle seventeenth century [Austria: United Provinces: England in Civil War and afterwards] and then others [Brandenburg-Prussia: Russia] whose revenue extraction grew and consolidated in the later seventeenth century. There is no observable correlation between the absolute levels or per-capita tax extraction rates and the states traditionally considered as absolute. Absolutism is not another word for state formation/consolidation, which was a broader-based phenomenon. 3. Military-Diplomatic Pressures towards State Consolidation:- Absolutism not about one sort of state being inherently more powerful than another. All European states were trying to respond to the huge pressures in the rapidly growing costs of war and the fact that there were deepening vortices of regional conflict (Italian wars (1494-1559): Dutch Revolt (1566-1609/48): Thirty Years War (1618-48), etc) making diplomatic alliances broader and more complex and rendering peace-making much harder. These pressures created two complementary trends in European political culture in the seventeenth century: a) exaltation of ‘order’ on the basis of political obedience b) emphasis on the importance of executive decision-making, of the power to command and control. Both these elements very clearly exemplified in the writings of the Dutch political philosopher Justus Lipsius (1547-1606) - Politicorum sive Civilis Doctrinae Libri Sex (On Politics, or Six Books of Civil Doctrine). 4. Absolutism: the history of a concept:- The term was unknown before 1789. The ‘ism’ was created in the aftermath of the French Revolution. It was popularised by Liberals in France who criticised the Restored Orléanist monarchy (and then picked up by Liberals in Spain (1820s)). English (Whig) historiography used it as a way of justifying English ‘exceptionalism’ in the English Civil War and the Revolution of 1688. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels used it as a way to explain the broader (‘progressive’) forces of modernisation against ‘feudal reaction’. German historians post-1870 also pictured absolutist states as rationalising, ‘enlightened’ forces for good. French historiography in the 20thC turned absolutism into an article of faith. 5. The ‘Myth’ of Absolutism examined:- As historical analysis has expanded to more detailed studies of institutions, tax-systems, court society, informal power structures, the relationship between the centre and the locality, etc, so the limited nature of the The European World: Absolutism (Greengrass) 2 achievements of absolute states has become clearer. Some (Henshall) say it (absolutism) never existed because there were never any ideological pretensions to absolute rule and the modest achievements of Europe’s monarchical states were in line with those of their dynastic predecessors:a) The ideological pretensions are examined through the ideas of the French philosopher Jean Bodin (1543-1596) (mixed reactions and bemusement to what he wrote, e.g. in Holy Roman Empire, Venice, and among Protestants) and his English counterpart Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) (open and public hostility in England; cautious respect in France and elsewhere). Their views seemed to rule out the expected role for the expanding groups of ‘stakeholders’ in monarchy. But no sign that they had any influence on the formulation of political ideas. JacquesBénigne Bossuet (1627-1704) gives us a better picture of how those at Louis XIV’s court justified absolute monarchy. It was very traditional, on the basis of patterns of divine rulership and patriarchy, derived from the Bible. So not much by way of distinctive ideology in absolutism. b) Not difficult to prove that ‘absolutism’ bears no relation to the way in which (e.g.) Louis XIV governed France. He did not ride roughshod over the Parlements (lawcourts) but by and large respected their privileges. His army rested on patronage and favour among officers, and it never satisfactorily resolved the huge problems of logistics it faced. The court was the focus for informal power-structures in the kingdom. Similar informal means were put to use when negotiating with the remaining representative institutions in the realm, which Louis XIV had no ideological objection to allowing to continue in existence so long as they worked in harness with royal objectives. 6. Absolutism as a Projection of Power:- Early-modern states were ‘theatre-states’, heavily reliant upon the projection of authority as a means of persuading local notables and élites to be loyal and serviceable. There is overwhelming evidence that absolutist states used the projection of power through traditional media (staged events – though not royal entries; palace construction; statues; paintings; ballet) in a more intensive and coherent way. They also utilised new mechanised media (tapestries; print; engravings; medals; coins; newspapers) and newly created cultural institutions (academies of science, music, painting, literature, etc). Absolutism is a way of delineating the coherent projection of royal power. 7. Absolutism as a Redefinition of the relationship between ruler and ‘stakeholders’:- The social bases of early-modern monarchy was based on an implied guarantee of political stability in return for the protection of the privileges of notables, mainly nobles (but ‘nobility’ was becoming a complex category) but also others (tax farmers, etc). Over and above the social basis of monarchy lay the social space that it accorded the élites to engage in politics. Absolutism restricted that social space, both by drowning out other views through the density of the projection of absolute authority (see 6), but also by building on a reluctance among those élites to engage in issues which created the kinds of divisions that had created crisis in the past (mainly over religion and politics). ‘Confessional absolutism’ further divided rulers from some of their stakeholders and, in the case of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685) created internationally vocal groups against the ‘absolutism’ of Louis XIV. The short-term result in absolutist states was the creation of an autonomous literary culture, largely divorced of political engagement. The long-term result was the creation of a critical intelligentsia that questioned the whole basis of absolute monarchy.