The Theology of Holy Communion - The Methodist Church of New

advertisement

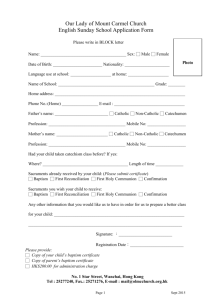

Leading the Celebration. Notes for People Newly Authorised to Lead Celebrations of Holy Communion. The Theology of Holy Communion and Its Embodiment in Worship. Rev David Poultney. Hamilton Methodist Parish. Notes on terms. Though this paper talks of the sacraments it is primarily about what we believe about and how we celebrate the Holy Communion or Eucharist. I use the terms Holy Communion and Eucharist interchangeably here. In the Methodist Church we have often talked of the Holy Communion or Lord’s Supper. This focuses on the receiving of the bread and wine. The word Eucharist, which we are using more frequently of late, comes from the Greek word for ‘ to give thanks’ and focuses on celebrating the goodness of God as shown in the history of both the people of Israel and the Christian community. In passing references to Roman Catholic practise I will use the term Mass; which derives its meaning from the Latin words of dismissal traditionally used at its conclusion. Who Celebrates? The Methodist Church entrusts certain persons to celebrate the sacraments of Baptism and Eucharist or Holy Communion. Ordinarily the sacraments are celebrated by presbyters, who at their ordination are charged with the task of celebrating the sacraments on behalf of the whole church. It should be noted that when a presbyter celebrates a sacrament it is not by virtue of a particular power he or she receives but because they do so for the whole church. The Sacraments do not belong to the presbyterate nor do they belong to the particular congregation where they are celebrated; they belong to the whole church. Because they belong to the whole church Methodist practice permits other people to be authorised to celebrate the sacraments. This authorisation is done by Conference exercising its ministry of oversight. It is usual for probationers to be authorised as they, though not ordained, are exercising ministry as presbyters. Also authorisation can be given both to deacons and to lay people. This authorisation is given to ensure that those who come to our worship services are not deprived of regular sacramental care simply because of any scarcity of ordained presbyters. The circumstances where this authorisation might be given are many and varied; perhaps you are part of a local shared ministry team in a rural area? Maybe you are authorised to celebrate for a particular community which worships in the language of one of our migrant communities? Whatever the circumstances under which you practice this ministry your authorisation will be to serve a particular community for a particular period of time, this period of time is open to review as per the pastoral need of that community. Whoever you are and whatever the circumstances of the sacramental ministry you practice you do so because you are entrusted buy the church to tell the story of God’s redemptive love in word and sign. The Methodist Context. The Methodist movement began firmly rooted in Anglicanism. Though we think of Anglican worship today as centred on the celebration of the Sunday Eucharist this was not always the case. In the Church of England at the time of John and Charles Wesley the average parish church would have celebrated the Holy Communion quarterly. In a sense this was a hangover from pre-Reformation Catholicism where the Eucharist or Mass was celebrated very frequently but lay people would very rarely receive communion. The Protestant churches have always maintained a clear connection between the celebration of the sacrament and the reception of communion buy those in attendance. This only became normative in 1 the Roman Catholic Church in the early twentieth century. The average Anglican service would have been one of the prayer services in The Book of Common Prayer (either morning or evening prayer.) The revival which birthed the Methodist revival was unusual in that it was not a preaching led movement alone but a sacramental revival too. John Wesley encouraged frequent attendance at Holy Communion and encouraged Methodists to attend their parish church whenever it was celebrated. He saw Holy Communion as “an ordinary means of grace.” Something ordained by God to provide us with spiritual nourishment and help us in our growth as Christians. Though John Wesley was a fervent and loyal Anglican who regarded the Anglican model of threefold ministry (bishop, priest and deacon) as superior to the nonconformist model of ordained ministry we now have, he was also clear that the sacramental nurturing of Christians takes precedence over the claims of any particular form of ministry. To ensure the care of Methodists in America he ordained men for ministry there though, by doing so he hastened separation from Anglicanism. He was prepared to break with Anglican practice and the received witness of the pre-Reformation church and – as a presbyter – ordain others to this ministry. What are we doing when we celebrate Holy Communion? Sometimes you will here talk of “high’ and “low” views of Holy Communion that correspond to “High Church” and “Low Church.” Though these are terms drawn from an Anglican context to describe the differences between the catholic and evangelical wings of Anglicanism they are useful to us as illustrations of difference. A high understanding of the Church and the Eucharist stresses a real sense of the presence of Christ which demands veneration and reverence. It also places great stress on continuity with the past and with traditions of worship. A low view stresses the church as a gathered community centred around preaching the Word and sees the Holy Communion as a memorial and as an act of obedience to Jesus; who commanded we do this to remember him. In reality people – and churches – are quite complex and you and your church may draw upon elements of both understandings. It is also worth noting that it is quite likely there are diverse understandings and backgrounds amongst your congregation. In my parish there are people from solely Methodist backgrounds alongside people who have come from Anglican, Baptist, Brethren, Pentecostal, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, Reformed and Salvationist backgrounds. This is an urban parish but rural churches are very often just as varied. Some denominations are associated with very clear and specific understandings about what ‘happens’ when we celebrate Holy Communion. For example both the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches have specific theologies about how Christ is present in the bread and wine of the Eucharist. Methodism has never had a formal theology of what ‘happens’ or how Christ is present in the celebration. For some of our ecumenical partners this can be a cause of frustration. This does not mean that Methodists have been or are indifferent to it and there have been many Methodist scholars who have contributed to a deeper understanding of Holy Communion. Methodist spirituality has been informed by Holy Communion, we see this in the large body of Eucharistic hymns by Charles Wesley, We rarely sing them nowadays but they are worth reading to understand what Holy Communion meant to the Wesleys. When Christians talk (and argue!) about the presence of Christ in the celebration of Holy Communion there is a range of differences but there are two positions I would like us to consider. That Christ is really present in the bread and wine and their true nature is as his body and blood once they have been consecrated. This is a somewhat simplified version of a traditional Roman Catholic understanding. 2 That the Holy Communion is a simple memorial meal, the bread and the wine are like his body only as signs or examples. This is loosely the position of the reformer Ulrich Zwingli and is generally seen as the polar opposite of the first position. Though there is not an official position I suspect a majority of Methodists, Presbyterians and members of the Churches of Christ hold something resembling the latter position. I recall presbyters I was placed with as a student talking about the Holy Communion as “only a symbol” and saying nothing “special” happens to the bread and wine. This view is comparatively rarer amongst Anglicans. It is worth reflecting that this was not what John or Charles Wesley believed. Charles Wesley’s Eucharistic hymns have a high view of the presence of Christ and John Wesley taught that Christ is spiritually (though not physically) present. This was also the view of John Calvin. Perhaps it might be helpful to understand what we mean by a memorial, as we often think of Holy Communion as a memorial meal. In the English language a memorial is a token of something or someone who is no longer with us. We see this most clearly in a headstone. Hence our understanding of the Holy Communion as a memorial meal has sometimes led to an observance which feels like the remembrance of someone dead and gone. This is a rather impoverished understanding of “in memory of me.” The New Testament firmly links the Last Supper in the tradition of Passover meals. In Judaism a family gathers at Passover to “remember” the liberation of the people of Israel from slavery in Egypt. An event that happened thousands of years ago. Part of the ritual of the meal is the youngest child asks the question; “Why is this night different from all other nights?” The answer is not “because tonight we remember when God acted to save our ancestors once upon a time and long ago.” The answer is “because on this night God delivers us.” A distant event becomes a living reality in the lives of the Jewish people and the Passover ritual re-presents those gathered at table with God’s redemptive action. It is this ability to make sacred reality present that is the power of worship. Whether in an emotional appeal in a revival meeting or in the beauty and art of Eastern Orthodox worship the Christian is represented with the power of God’s redemptive love. Many of us are familiar with the song “How is Jesus present?” The song shows us a reality, that we encounter Jesus – amongst other places – in worship. What might it mean then to celebrate Holy Communion aware that the reality of God’s love is present in this celebration? It does not mean that there is a particular ‘magic action’ or that the bread and wine are necessarily transformed. Contemporary theologians often do not see particular transforming act or set of ‘magic words.’ The whole service is our celebration and thanksgiving and the reality of God’s redemptive,l ove is made present in the whole. In the words and prayers, in singing and action. in the prayer of consecration and in the sharing and in the peace and love nurtured by celebrating together. Such worship does not have to be high church or low church, it is embodied in the particular context of the community gathered in worship. Whatever ritual and action we undertake though should be done with thought, care and love. Some closing thoughts. What makes the celebration? Traditionally theologians have seen the sacraments as authenticated by certain things. 3 Right intention. That this is meant to be a celebration of the Eucharist as celebrated by the Church throughout its history. This is authenticated by the celebration being led by an appropriately authorised person using an approved form of worship. For Methodist this means it is led by a presbyter or by another person licensed by Conference. Our approved liturgical texts, including the published order for Holy Communion, do not have the same binding status as The Roman Missal for Roman Catholics or A New Zealand Prayer Book for Anglicans. However the church would hold that a celebration of the Holy Communion must include two specific things. The words of institution. The words we use that Jesus is recorded as using about the bread and wine being as his body and blood and his instruction that we are to remember him when we do this together. Invocation of the Holy Spirit. Calling upon the Holy Spirit to bless the elements and to bless the gathered community. Around these two things there are a range of prayers and actions which might or might not be appropriate according to the community where the celebration is happening. Right Action. We Methodists have tended to be more rigorous with this in baptism. You could hardly baptise someone without pouring water on them or immersing them in it. Yet I have seen Methodist celebrations of Holy Communion where the celebrant does not touch the plate of bread until it is time to break it or the cup until it is time to receive from it. On one occasion I even saw a presbyter lead the service without uncovering the elements. I do not recall these to sound fussy or to imply that these celebrations were not valid. Symbols are powerful and important. So why not lift the plate when saying the words of consecration over the bread and then lift the cup? Of course this might seem to priestly for you or your congregation but it is always worth thinking through the possibilities of symbolic action. Right Substance. The substances the Christian tradition assert are right for use in Holy Communion are bread and the juice of the grape. Generally speaking for Methodists this is leavened bread and grape juice. When we celebrate Holy Communion it is not ours alone, it is not an act solely for this congregation at this moment in time. It is an act in continuity with a tradition of celebrations over the centuries and on into the future. This is important to remember as we occasionally here suggestions of using other elements; coconut flesh and coconut milk perhaps (for a Pacific community) or pizza and coke (for a children’s service.) Ask yourself how a visitor from another tradition would feel if he or she attended a Methodist Holy Communion like this? This is not an argument on my part for saying we must never be distinctive or different, or that we must never do anything which might offend anyone’s sensibilities but we need to recognise that we do not possess the Sacrament; we celebrate it as part of the whole Christian community. 4