Nature and Purpose Of Religious Art Nature and Purpose of

advertisement

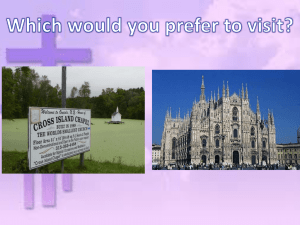

Nature and Purpose Of Religious Art Nature and Purpose of Religious Art What is religious art? Religious Art is unusual because it does not describe art of a particular style, period or region e.g. Renaissance Art refers to art created around the 1400’s in Europe, which was known as the Renaissance. Impressionism was a 19th century art movement that began in Paris and gets its name from a piece of work called Impression Sunrise by Claude Monet (right). Instead theReligious term Religious Art describes a particular range of purposes, whichacover The term Art describes a particular range of purposes, which cover wide a wide range of forms and styles (Beth Williamson Christian Art: A Very Short Introduction) range of forms and styles (Beth Williamson Christian Art: A Very Short Introduction) “Christian art” has some different meanings. Mainly, the fine arts found in the service of the Church: eg constructions or embellishments in houses of worship, homes of the consecrated servants of God, Monasteries, convents, and last restingplaces of the faith, or arts used in rites and ceremonies of the Church. In this sense, Christian art is also called Ecclesiastical art. Secondly Christian art is sometimes also used to describe artwork inspired by Christian ideals and principles, eg paintings and sculptures separate to the places of worship. (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03710a.htm) One of the interesting things about religious art, particularly Christian, is that it often includes a wide range of other subjects, such as history, politics, theology, philosophy, science and many more. Christian art began small, in very restrictive circumstances in tiny persecuted communities, coming out of Judaism, and has now developed into an almost universal presence in the public buildings and private spaces across the world. When considering the fact that Christianity came out of Judaism, it is important to remember that within the older religion there was a view that to create images of God or religion was to create idols which had neither spirituality in them or anything linked to God. However, the Greeks and Romans who were also converting to Christianity came from a background of celebrating their worship with statues, pictures and monuments. It would seem obvious that the two cultures clashed and split, however, the Judeo-Christians adopted the idea of celebrating worship with Statues and imagery. Max Weber and George Simmel, classical sociologists, regard religious art as ‘social fact’ arguing that ‘art empowers the soul to supplement one world with another and thereby to experience itself at the point of union.’ In other words, religious art offers the chance to visualise religious ideas such as heaven, hell, and God, and offers a religious experience for the believer through the art itself. The French Sociologist Emile Durkheim stressed importance of the connecting relationship of religious art objects with their specific functions to religious beliefs and points of view. This has been an active concern of art historians for some time. Some accept this without question, others seek to show how clear the relationship is. Problems with classification of religious art Firstly, care must be taken in making assumptions about iconicity or importance of religious symbols and the ‘creative’ character of visual images. Some artists believe they were guided by God in creating their master pieces, can we argue this is not the case or vice-versa? As Richard Wollheim argued, we must always take account of the believer as well as our own view. A second problem is that there are real difficulties in distinguishing between religious art as a set of symbols giving information about the content and place of religion in a society, and the same art functioning for individuals within that society. Thirdly, there is the difficulty of distinguishing between the physical representation of the sacred as an art product, and as a cult object. This problem is seen clearly when religious artefacts are reproduced on a mass scale and sold to tourists, e.g. Images of Mexico’s ‘Our Lady of Guadeloupe’ are one such example, and what African retailers often call ‘airport art’ another. Finally there is the ‘traditional’ descriptive difficulty of whether or not to regard religious art, along with religion or art itself, as a free-standing category of ideas and experience, or essentially, as no more than the visual spin-off from political, social, cultural and institutional activity. Implicit Art: Art which has implied – suggested religious connotations e.g. inspirational art. Explicit Art: Art which is clearly religious e.g. Icons, Illuminated Manuscripts The Range of visual art in religion There are three main ranges of visual art in religion; Obvious, less obvious and more contemporary. Obvious: Type Architecture Wall Paintings Stained Glass Religious Paintings Description Sacred architecture focuses on buildings; looking at geometry, iconography and the use of sophisticated signs, symbols and religious motif. Christian churches in the Middle Ages featured a cruciform plan, meaning the layout took the form of the cross. It consists of a nave, transepts, and the altar stands at the east end. Modern churches span several styles with similar characteristics resulting in simplification of form and the elimination of ornament. Wall paintings are a unique art form, complementing, and yet distinctly separate from, other religious imagery in churches. Unlike carvings, or stained glass windows, their support was the structure itself, with the artist's `canvas' the very stone and plaster of the church. They were also monumental, often larger than life-size images for public audiences. Notwithstanding their dissimilarity from other religious art, wall paintings were also an integral part of church interiors, enhancing devotional imagery and inspiring faith and commitment in their own right, and providing an artistic setting for the church's sacred rituals and public ceremonies. Stained glass has been used in churches for over 1000 years. The design of a window may be non-figurative or figurative; may incorporate narratives drawn from the Bible, history, or literature; may represent saints or patrons, or use symbolic motifs, in particular armorial. Windows within a building may be thematic, for example: within a church - episodes from the life of Christ; within a parliament building - shields of the constituencies; within a college hall - figures representing the arts and sciences; or within a home - flora, fauna, or landscape. The earliest religious paintings can be found in the catacombs in Rome and date around the 3rd Century. Interestingly the paintings do not tend towards the Crucifixion but focus on Jesus as the Good Shepherd leading his followers to the truth. It is only later during the Medieval period that the focus moves towards the Crucifixion and the messages surrounding it. Modern Religious paintings tend to vary in focus, and are often mass reproduced along with earlier paintings. Statues Images Religious statues have featured in worship as long as other forms of art. They tend to represent the different types of religious icon and historical figures that are looked to for guidance and reassurance. Some see religious statues as a symbol or provide insight, reassurance or encouragement. Many people use for example Religious Statues of their favorite or patron Saint, they believe that by praying for their assistance these Saints will intercede on their behalf with the Lord. But a few of the faithful actually believe that members of the religious icons and Religious Statues actually have spiritual power or significance of their own. These people think that in some manner that the actual Religious Statues have spiritual significance and power in their own right. Christian images and symbols have been used for centuries as a way to identify each other. The Cross is the symbol of Christ’s suffering, emphasising for Christians what he did by suffering for them. The fish – Ichthys – came about due to the persecution of early Christians who were perceived as a threat by the Romans. Animals are used throughout the Bible with literal and symbolic meanings. Colours also have meaning within Christianity e.g. blue means heaven and wisdom. The triquatre is a symbol of the holy spirit – God in 3 Less Obvious Type Illuminated manuscripts Icons Description ‘Manuscript’ is Latin for handwritten. Before printing Bibles had to be written by hand. This was a laborious process which could take months or years. Most of the work was produced on vellum which was made from deer-skin; a large manuscript might use one whole cow to produce 3 or 4 sheets of paper, and a thick book could require the hides of whole herds. This meant that such books where very expensive. Some manuscripts were made even more precious by ‘illumination’. This term comes from the Latin word for ‘lit up’ or ‘enlightened’ and refers to the use of bright colours and gold to embellish initial letters or to portray entire scenes. Sometimes the initials were purely decorative, but often they work with the text to mark important passages, or to enhance or comment on the meaning of the text. Art historians use the term ‘icons’ much narrower than the Greek Eikon which it derives from. The earlier greek term includes all images. But the modern understanding is an image painted on a panel. The earliest surviving icon’s date from the 6th Century, although it is clear they existed earlier than this (200AD). The portrait in the icon is crucial as it is believed to be an accurate representation of the figure, which is why they are painted today as they were when they were first painted. Icons are found mainly within Greek Orthodox, and some in Catholicism. Protestantism rejected the idea of icons believing them to be blasphemous and idolatrous and against the true meaning of Christianity. Illustrations Propaganda material Religious furniture Artefacts Act of worship itself Religious texts, particularly the illustrated manuscripts, are filled with illustrations which hold symbolic meaning. Whether religious people, or representations of earth, animal, heaven, or flowers. Modern illustrations continue to hold religious symbolism and meaning. In some cases the illustrations are provided to add to the story, or in some cases tell the story itself. Not all illustrations are within religious texts, but all include a message. During the reformation, starting in 1400’s, crude comic strips were created because literacy rates were low. These forms of communication featured drawings that conveyed message and included simple, briefs rhymes that enabled peasants to connect the picture with the desired message. The goals were to take action and change the way things were. In more recent times Christians have produced material includes doctrine against films and books such as Harry Potter Religious furniture whilst not considered ‘holy’ or ‘sacred’ plays an important role within Christianity. Publically furniture such as Lecturns, Altars, ceilings, seats and many other items are finely carved and ornately decorated to show their significance. Privately; crucifixes, icons and artwork. Similarly to religious furniture, artefacts such as altar pieces, miserichords, funeral monuments, church plate, vestments, and so on, whilst not often considered ‘sacred’ have an important role during worship. In many cases they are finely carved or ornately decorated. John 4:23 "Yet a time is coming and has now come when the true worshipers will worship the Faith in spirit and truth, for they are the kind of worshipers the Father seeks. God is spirit and his worshipers must worship in spirit and in truth." 1 Corinthians 10: 31: "So whether you eat or drink or whatever you do, do it all for the glory of God." 1 Peter 4:9,10: "Offer hospitality to one another without grumbling. Each one should use whatever gift he had received to serve others, faithfully administering God's grace in its various forms." Singing has long been a part of worship, it is known the early Christians meeting in secret in Rome in the first century sang together. Dance, and theatre and other visual spectacles have also been adopted into worship: medieval passion plays, modern theatre, even film: the passion of the Christ. More contemporary Type Video art Description Viola uses video to explore the phenomena of sense perception as an avenue to self-knowledge. His works focus on universal human experiences—birth, death, the unfolding of consciousness—and have roots in both Eastern and Western art as well as spiritual traditions, including Zen Buddhism, Islamic Sufism, and Christian mysticism. Using the inner language of subjective thoughts and collective memories, his videos communicate to a wide audience, allowing viewers to experience the work directly, and in their own personal way. The Purpose of Religious Art Graham Howes identifies four distinct dimensions to the relationship between religious art, religious belief and religious experience. Although they are inseparable, it is possible to break them down slightly: 1. Iconographic and Devotional Iconographic refers to the personal side of worship, through the use of icons. Icons are images of saints or holy persons (right is an icon of Christ). The icon is not simply worshipped, but a window through which the unseen world looks onto ours. For some worshippers, icons act as intermediaries, between God and the Worshipper. An eighteenth century theologian John of Damascus put it, icons ‘contain a mystery and, like a sacrament, are vessels of divine energy and grace ... through the intermediary of sensible perception our minds receive a spiritual impression and are uplifted towards the invisible divine majesty.’ However, working as channels of grace like the cross and the Gospels, icons are important but they are not in themselves holy. The icon depicts and shares in the sanctity and glory, which means it receives veneration, but not adoration which is for God alone. Icons are mainly found within Greek Orthodox religion, and within Catholicism. The Protestant movement found the idea of icons ‘idolatrous’ and ‘blasphemous.’ In many cases the Protestants activity attacked the places of worship, removing many of the ‘idolatrous’ images, altars and such, as was seen throughout England at the time of the Reformation and throughout Europe with the Movements of Lutheranism and Calvinism. More recently Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury argued, ‘all art should be liturgical’ in other words, should be direct to God. 2. Didactic Didactic means educational, moralising, improving and refers to this aspect of religious art. European Gothic Art of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were used in a didactic nature. As early as 1005 a local synod (church council) at Arras had already proclaimed that ‘art teaches the unsettled what they cannot learn from books’. This area of religious art was much more than a visual stimulant, it served for religious insight and spiritual awareness in the worship of God. Abbot Suger of St Denis in Paris described it: “I see myself dwelling in some strange region of the universe which neither exists entirely in the slime of the earth nor entirely in the purity of heaven; and that, by the Grace of God, I can be transported from this inferior to that higher world in an anagogical manner ... transferring that which is material to that which is immaterial.” In other words, the place of worship as a building itself had the ability to lead the mind from the physical world, to the divine and make spiritual things visible. The Cathedral at St Denis was also felt to be just as important for it’s technical excellence, as a feat of engineering and intellect, as it was for its spiritual and culturally reflexive qualities. Pope Gregory the Great (590-604AD) stated that Christian art was the ‘books of the illiterate.’ In a letter to St Serenus, the bishop of Marseilles, Gregory said: “What writing does for the literate, a picture does for the illiterate looking at it, because the ignorant see it in what they ought to do.’ And ‘Painted likenesses [are] made for the instruction of the ignorant, so that they might understand the stories and so learn what occurred.” To the left is one of the stained glass window’s at St Mary’s Parish Church in Dundee. It depicts the parable of the Good Samaritan. To the right and left are the Levite and Priest, in the centre the Samaritan helps the injured the man. The significance of the Samaritan in the centre was that it shows the right action. Another example can be found in the ceiling of Carlisle Cathedral, built 1122. The ceiling is a dark blue covered with stars, depicting the heavens. This was to signify that prayers rose to heaven. Just beneath, are two rows of gilded figures, these represent the angels in heaven, and beneath are the saints, and on the cornices are the apostles. They are not just images, but were created to remind the Medieval Christian of what his prayers and beliefs were for, leading him to heaven. 3. Institutional The concept of Institutional Christian Art, is that many institutions hire someone to create religious artworks for them. In this sense the artist did not necessarily need to have their own vision, or be guided by some inner voice, they merely did what was required of them: “the artist did not have to worry about ‘feeling’: he was given his assignment – his Crucifixion or his Virgin – and knew perfectly well, down to the last gesture and the last fold of drapery, what he had to In the fifteenth century for example, the church seems to have found no difficulty in do. The religious formwas wasovertly accepted by both parties.” Howes.that paganism accepting sacred art that frivolous and worldly Graham in treatment, established a comfortable appearance: the face of the Green Man appears in many churches from this time (below right the Green Man of Canterbury Cathedral’s Black Prince’s Chantry). In the nineteenth century there was a great change. It was rare for a great master to work in a religious building, unlike the Da Vinci’s of the past working in the Sistine Chapel. For the first time in history a great artistic movement arose without any true connection to religion; impressionism. Since then all development in art, sculpture, painting, and so on, has done so outside of religion, and in some cases their development has challenged religion, spiritually and morally. Think of Damien Hirst’s sheep in formaldehyde and the outrage that first caused when it was placed on display. This has lead the Church to ask what part can it have in the future of art, when it stands against some of the new developments. 4. Aesthetic The Aesthetic Christian Art concept arose because of the modern issue of Institutional Art. Tillich describes it as: “sentimental, beautifying naturalism ... the feeble drawing, the poverty of vision, the petty historicity of our church-sponsored art is not simply unendurable, but incredible... it calls for iconoclasm.” It is the concept of the reproduction of art for the masses. Within the protestant tradition, Holman Hunt’s ‘Light of the World’ rapidly became a widely distributed icon in many Victorian house-holds. This was not an isolated incident, and occurred not just within Protestantism, but also within Catholicism, and wider throughout the Christian denominations. The art is useful to the Church. Sometimes they have a dual function, serving as vehicles of national identity as well as personal devotions, for example Mexico’s ‘Our Lady of Guadeloupe’ and Peru’s ‘Lord of the Miracles’. However many modern artists avoid it for the dominant aesthetic, the ones everyone appears to ‘want’ is to narrow to allow any personal interpretation of the Gospels and truth. Whilst this appears pessimistic, that the masses will go for the most obvious, without needing to ‘de-code’ the artwork, at the same time there is nothing to prevent the artist from doing what they desire. But these are not the only purposes of religious art, there are others that Howes has not identified in his dimensions: 1. Art as aid to prayer and worship Whilst Howes discussed iconographic art, focusing mainly on icons and images, he does not identify the more ornate art that has a purpose in worship but is not in itself ‘holy’. For example the lectern (left) is designed to hold the Bible from which readings of the Gospels take place. It is significantly important in that it plays an important part in the service, holding the Bible whilst the Gospels are read. It is usually finely carved out of wood or crafted in brass. Often the image of an eagle is used, showing the might and power of the word of God, sometimes lions are also depicted on the legs for the same purpose. In public worship, churches and cathedrals are used and have a cruciform design, showing the importance of the crucifixion, reflecting the use of the building and also the hierarchical organisation of the church and cathedral. In public places of worship architecture is also used to give a sense of the numinous. 2. Creating a sense of the numinous Historically there are two permanent symbolic attributes of ‘high church’ architecture. First it provides a religious environment, a mood, an ambience, in the sense that it evokes the ‘numinous’. The idea of ‘numinous’ comes from Rudolf Otto, who says the term implies an additional dimension over and above mere goodness, with several facets of meaning. First of all there is the element of awfulness, that which evokes the ‘fear of God’. It is almost a primitive reaction to the fearful majesty of God. Secondly there is also a sense of energy; power, might, transcendence and mystery are some of the qualities of the numinous. They hold the individual in a grip of awe and fascination. The ‘numinous’ will be used for the architectural expression of the ‘mood, the ambiance’ that church architecture displays. The numinous can be found in churches from the earliest times eg Stonehenge, pyramids. Western architecture implies the numinous through negatives like silence and darkness. Silence is certainly a negative quality associated with churches and temples, "Yahweh is in his holy temple, let all Earth keep silence before him". It is still common to regard noise in a church as sacrilegious. 3. Propaganda and political statement Kings and rulers would use Christian imagery to bolster their own ideologies and political rhetoric. Religious art was also used to put over religious propaganda. Christian art was transformed by the Reformation. The Reformation is a term which applies to more than one movement at different periods of time in history. The are two main strands: The Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Reformation. The first is a collection of movements that fought to break away from the pope around the 16th century, and continued to develop the different protestant religions: Church of England. A great many works of art were created during the fight at the beginning of these movements. For and against by both Protestant and Catholic artists. As the Protestant movement grew, so did their work. With the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII much of the religious Catholic art in the country at that time was destroyed, ornate altars ripped out of churches, entire monasteries and buildings destroyed. The Protestant movement preferred a much simpler place of worship, seeing no need for adornments and ornaments which some referred to as blasphemous and idolatrous. This lead to the rise of priest holes and places of hidden worship, for those who wished to remain part of the Catholic faith. During Queen Mary’s reign, Protestantism was illegal and many were executed for their belief’s, some burnt at the stake, many imprisoned for their faith, only offered freedom if they rejected the ‘new’ faith, many artworks were created reflecting this time. After Queen Mary’s death, the Country reverted from Catholicism to Protestantism. Although Queen Elizabeth I allowed both Catholicism and Protestantism to be practice in the country, the dominant religion became Protestantism, and much of the Christian artwork in this country since that time comes from that denomination. 4. Art as expression of status and wealth People would also commission religious art as they saw it as a way of decreasing their time in purgatory or not having to go at all. Instead they would go straight to heaven. During the Medieval period, some wealthy landowners would patronise (fund) convents or monastery’s, in doing so ensure that the nuns or monks would say prayers to guarantee them a place in heaven, whilst at the same time, showing off their wealth and power in having such monuments on their land. They believed that architecture could point to authority and the power of the religion, or certainly in Christian terms, the power and wealth of the benefactor In the home, there would significant religious symbolism, showing again their status and wealth. The most powerful expression of status and wealth connected to Medieval Christianity, was Henry VIII’s reformation. 5. Art to help process of canonisation Canonisation is the process before a deceased Christian becomes a Saint. It is a form of recognition for great work, but holds great religious significance for Christians, showing that God was working through that individual. For example some argue that the work Mother Teresa did in Calcutta for the sick and needy was evidence of God working through humans, and the process of canonisation has begun with petitions for her to recognised as a saint. In some cases, religious artwork is create to illustrate the case. An example painting is St Louis of Toulouse by Simone Martini (left). The painting shows Louis performing miracles and healing the sick. Showing what he has done in life in order for him to become a saint. The work was created before St Louis was canonised. Distinctive Features of Christian Art Heading Architecture Symbolism Subject Matter Non representational form Writing Particular artefacts Art for liturgical purposes Notes As previously discussed Christian architecture has a distinctive style and design, with many symbols and meanings. Again as previously discussed; cross, crucifix, fish, triquatre, dove, and so on. Symbolism of particular people, eg Virgin Mary, Jesus, Saints, Bishops etc. There are many different forms of subject matter in Christian Art: Mostly Representation of figures eg Saints and Martyrs, Bishops, teachers, Also patterns, or contentious subject matter: drugs, same-sex marriage. Non-representation form merely means that without images, for example carefully crafted Manuscripts, and patterned designs in mosaics or carved into furniture. Often they hold significant meaning. Illuminated manuscripts often contain images and colours each containing their own meaning and symbolism important for the religious believer, literate and illiterate. Most artefacts found in a church have significant meaning, eg altar pieces, lecturns, misericords, candels, flowers, church pews, screens, etc Art should be directed to God: Ceremonies, dance, singing, etc Art in Worship in Christianity. Private worship: May be at home, or alone in a place of worship: eg in the mother’s chapel, focusing on private prayer, or contemplative worship (mediatation) Type Devotional Inspirational Unifying Worshippers Providing a focal point for worship Public worship: Usually in groups, as part of congregation or choir. Often in a specific place of worship: church or outdoors Description Art as an aid to prayer, meditation, etc. e.g. icons. How does the art of a particular religion draw the viewer towards a higher realm? In what ways can art be inspirational? Art participating in corporate worship, e.g. dance, or architecture by enclosing a ‘sacred’ space in which worship is conducted Art focusing the mind on worship or during worship e.g. altars during the Eucharist, altar pieces reflecting Visual forms of the liturgy and liturgical objects and vessels. different times of the ecclesiastical year. Vestments, candelabras, communion plates and many more objects hold significance during worship, and may be very finely crafted, but are not considered themselves ‘holy’. Importance and significance of Religious Art for the Artist and Community. For community: Whilst it is well documented that religious institutions commissioned art for churches and establishments, with strict rules and requirements, it is clear that the art produced also has touches of personality. Whilst created to be didactic, liturgical and inspirational, giving a sense of the numinous, many examples of communal religious art also adds something from the personal. The misericords at Cartmel Priory in the Lake District, were chosen directly for the first monks who were to be seated upon them. The prior’s stall contains the letter William which has been taken to refer to Prior William who commissioned the work. The others contain different symbols on each seat. There were five main complex reasons for commissioning art; credal, institutional, political, artistic and personal. Credal relates to a set of beliefs or statements. There are many creeds that are said by Christians such as the Apostles Creed (below) which has influenced many art works, paintings, sculptures and carvings: 1. I believe in God the Father, Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth: 2. And in Jesus Christ, his only begotten Son, our Lord: 3. Who was conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary: 4. Suffered under Pontius Pilate; was crucified, dead and buried: He descended into hell: 5. The third day he rose again from the dead: 6. He ascended into heaven, and sits at the right hand of God the Father Almighty: 7. From thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead: 8. I believe in the Holy Ghost: 9. I believe in the holy catholic church: the communion of saints: 10. The forgiveness of sins: 1l. The resurrection of the body: 12. And the life everlasting. Amen. Institutional art in the Middle Ages was often commissioned to be a certain style and form, giving out a certain message. It was often didactic in design, sending out a message, in particular stained glass in order to give a message to the those who couldn’t read. Political art in the Middle Ages was often to show power and wealth. The Sistine Chapel was painted 500 years ago by Michelangelo Buonarrati, as directed by Pope Julius II to show his papal power and significance, leaving his ‘mark’ before he died. English Kings and Queens were often depicted in their portraits with some religious symbolism or imagery in their paintings. Modern political art often has a deep clear message, either anti-drugs, anti-war, or promarriage. It often uses liturgical context to get it’s message across, but sometimes misses it’s audience. The problem with political art is that sometimes the work lost it’s religious meaning, being significant for who painted it, how much it cost, or the overt political message involved, rather than it’s spiritual meaning. Artistic and Personal another angle of religious art for the community is marking significant events, time or seasons, and conveying deeper religious truths. For the artist: For some artists religious art is an expression of outworking faith. In other words a form of worship in itself. This is most easily seen in singers who choose to sing religious songs, such as Gospel Choirs, and Leona Lewis’ Footprints in the Sand. But other artworks are also a form of religious expression. Josefina de Vasconcellos’ sculpture of Archangel Michael (left) stands proudly in place in Cartmel Priory in the Lake District. Create in the 1930’s it represents St Michael fighting against the jaws of evil. She also wrote Christian poetry as an expression of her faith. Within Western Christianity it is easy to single out particular artists, as they often leave signatures or something which identifies them as the person who has created their piece of art. Within the Eastern Orthodox tradition of icon painting, it is very different. Icons are usually produced by priests whose work is unsigned. The Sound Council of Nicaea in 787AD said: “Icon painting was not invented by painters; it is, on the contrary, an established institution and tradition of the church” and that “Icons are in painting what the Holy Scriptures are in writing: an aesthetic form of the truth, which is beyond the understanding of Man and cannot be comprehended by the sense.” Before even beginning to work on the icon, the priests will fast, pray, confess and go to communion. The method of creating an icon does not change from person to person very much, and is virtually identical to that first formally set down in the early tenth century. In Western Christianity it is very different. Whilst Medieval monks worked on their illuminated manuscripts, all similar in fashion, they selected the images they wanted to add to the pictures, all with specific symbols and meanings. Artists themselves began to create different forms of art. Whilst Italy was responding to the advent of realism, Germany and the Netherlands were creating very individual interpretations of religious themes (Durer, Memling), and Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro transformed the pictorial depiction of Biblical narrative (1606-69). Rembrandt was brought up in the Protestant Reformed Church, but it did not influence his work, inducing him to create liturgical art or one created for a church setting. Instead, his was more meditative art, centring around individual consciousness, on the states of the soul in themselves, and then on their relation or non-relation to others. Visser ‘t Hooft said: “Rembrandt was the painter of the grace of God, exhibited to the unworthy, the unimportant, those without merit, in such a way that only the grace of God mattered.” And “Rembrandt’s Christianity cannot be defined in terms of the Church, but is the result of his personal encounter with the Bible.” It is known that his mother read the Scriptures to him as a boy, and that he stood Latin at school and read the Bible, and that as an adult he found pleasure in reading the Bible. All this, as Howes states, “reinforced both his religious and artistic identity”. For both groups: Both groups are interdependent on each other, the artist needing the community to buy the art, and the community needing the artist to produce the art. Some artists may argue that this is not the case, their art needing no-one but them, but often validation is required. For both groups, art is a sign and symbol of relationships, e.g. patronage, the artists work is funded by the community, and relationship with the divine for both. What is interesting to consider is the changing use of art, how it is depicted and how it expresses the meaning, but that the meaning itself never actually changes. The word of God in the Bible is the ultimate, and cannot be altered no matter what the art says or does. Relevance of Religious Art today Looking back to the first Christians, a small fledgling group persecuted by the current authorities for their beliefs, in some cases killed and martyred. Whatever artworks they produced has not survived through those times. The earliest art surviving art shows that Christians were trying to spread the message of Jesus the Good Shepherd. As you look through history you can see the message, though still spreading the word of God and the Gospel’s ‘good news’, however the form of the message alters. In the early church Jesus is the Good Shepherd leading his people from darkness to heaven. Through to the Middle Ages focusing on how Jesus died for the sins of the world. To the modern message of Jesus’ love for humankind. Showing the opposition of iconoclasm of 8th century and the Protestant Reformation, where religious art was seen as being of secondary importance to the ‘word’ and often resulted in deliberate destruction of visual art. Religious art has been used for many reasons, political, personal, violent, and so on. But where is it’s relevance today? Although today’s society is far more literate, in 2010 around 24% of England’s adults are illiterate compared to 70% of the Middle Ages, many people still gain a great deal from visual illustrations. Many people today use the visual as means of expressing key ideas and religious ideas. (Think of your VAK in your lessons at school). Modern artists have produced what might be considered Christian Art, dealing with many of the same themes and concepts that we have already seen, but which were never designed to function as part of Christian worship. The art is not created to fulfil a Christian function, but they were designed as independent artworks, to be displayed in the modern setting of the art gallery and museum, rather than in a church. Nevertheless, these works gain their reputation by referring to well-known Christian images and concepts from the past. Preservation of Art Some of the historical artworks of our country and in the Christian World, being nearly 1800 years old, needs a lot of care and attention. Some argue that the cost, which is often immense, outweighs the need to care for these ancient artworks. Whilst others would say their message is just as important as work created today. For some it is more important, some claiming to be closer to the true meanings. Most would agree that historically all have value, also religiously. But what does this say about the relevance of ‘religious art’ in contemporary society? Is it being preserved or produced purely from an aesthetic perspective, a religious perspective or both? Bibliography Howes, Graham (2007) The Art of the Sacred: An Introduction to the Aesthetics of Art and Belief. London. I.B.Tauris. Williamson, Beth (2004) Christian Art: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Knight, Kevin (2009) Catholic Encyclopedia. Accessed at URL (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03710a.htm on 17.08.10 Resources for Catholic Educators (2010) Art and Christianity. Accessed at URL http://www.silk.net/RelEd/relart.htm on 17.08.10 Streich, Michael (2009) Reformation Printing and Propaganda. Accessed at URL http://www.suite101.com/content/reformation-printing-and-propaganda-a106254 on 19.08.10 Viola, Bill (2010) Bill Viola: Artist Biography Accessed at URL http://www.billviola.com/biograph.htm on 20.08.10 Singh, Daljit (1998) Christian concept of sacred space. Accessed at URL http://www.absolutearchitecture.net/Dissert2.htm on 20.08.10 Section B Religion, Art and the Media 5 (a) Examine the range of religious art. Candidates may, but need not, refer to one religion only. Answers should reflect the wide diversity of art forms in religion. Possible forms include reference to architecture, stained glass, music, images and statuary pictures and illustrations; examples should be offered with some comment. Range is important but not all forms need be present. What is required is a clear understanding of the range of what can be termed ‘religious art’ and reasons why and how it is deployed’ (30 marks) AO1 (b) To what extent would you agree that the main purpose of religious art is to represent the divine? Awareness of the diversity of purposes in art with reflection on which, if any, purpose could be considered the main or most important. Some clear evaluation of nature of purpose, is it always representative of divine? Expect reference to religious art as, e.g. inspiring awe and wonder, contributing to sense of numinous, use of art forms in liturgy (e.g. music, dance, etc.), didactic purpose (e.g. stained glass), decorative as well as representational and criticisms of any attempt at representing ‘divine’ if appropriate in context’. (15 marks) AO2 6 (a) With reference to the art of one religion you have studied, explain the contribution of art to worship. A wide range of response possible here but answer must be confined to ONE religion. Clear reference and to and understanding of art in the context of worship is required by the question. Reference can be highlighted in various ways:- e.g. in the production of and veneration of Icons; architecture , music, role of art inspiring the sense of the sacred, unifying worshippers in action (e.g. dance drama & music etc). The structure of sacramental worship or the ritual of worship as art or theatre can also be considered. (30 marks) AO1 (b) Assess the view that the true significance of religious art can be understood only by a religious believer. This may be approached through a consideration of the nature of symbolism or of a spiritual dimension within the work of art available only to a believer. Alternatively, appreciation of art may be considered simply to be a personal response not an intellectual unpacking – in which case ‘significance’ is subjective and cannot be argued as ‘true’ or ‘false’. All points should be supported with explanatory examples / illustrations and some conclusion should be reached. (15 marks) AO2 7 (a) With reference to two works of fiction, explain why religion is a popular theme in fiction today. Answers are context dependent but reference may be made to (e.g.) universal concerns about death, suffering, meaning and purpose of life; pressure of 21st century living raising ‘angst’; new age philosophies and pluralism. Bandwagon effect. Inheritance from previous generation of literature – revival in films. Commercial success and piggybacking. (30 marks) AO1 (b) ‘Religion needs humour.’ To what extent is this claim true? Various points may be made with examples / illustrations. Disagree Some humour regarded as divisive, blasphemous and / or inciting racial hatred. Seen as trivialising religion, which in turn is seen to require serious moral self discipline and respect for the sacred. Humour can be seen to be at the expense of others. Alternatively Humour may be a way of penetrating the illusion of the ‘real’ world to suggest a reality beyond. Formal religion can be seen to obscure the ‘spirit’ and humour to puncture that formality. Joy in ‘God’s creation’ or in spirituality is considered more important and accessible than intellectualising. All points should be supported with explanatory examples / illustrations and some conclusion should be reached. (15 marks) AO2 8 (a) Examine the role of the Internet in promoting religion. Examples of ways internet is used to promote religion (information, evangelism, propaganda, religious practice, theological debate) using web sites chat and forums online worship environments and e-mail. Mainstream and minority groups (e.g. neo-paganism) are represented. Quality of site does not indicate religious authority. Note can also be used to promote anti religious agenda. (30 marks) AO1 (b) Discuss how far televangelism establishes a cult rather than promotes religion. Look for some explanation of nature of ‘cult’ and explanation of ‘religion’. Look for evaluation of question. Establishes cult Charismatic leaders (e.g. Jimmy Swaggart, Jim Baker). Discourages social engagement with those outside cult. Often makes financial demands upon followers. But promotes religion Popularity suggests they do meet a spiritual need better than mainstream churches. Bring religion to housebound, etc. (15 marks)