Chapter Outline I. Types of Mood Disorders

advertisement

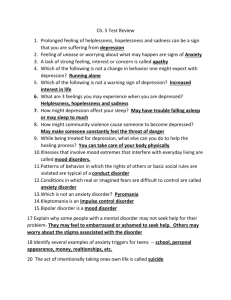

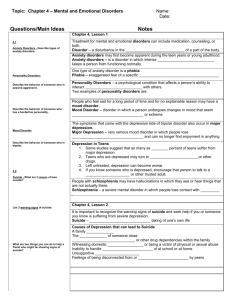

CHAPTER EIGHT MOOD DISORDERS AND SUICIDE Learning Objectives 1. Describe the features of major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder and distinguish between them. 2. Discuss the prevalence of major depressive disorder, with particular attention to ethnic and gender risk factors. 3. Discuss seasonal affective disorder and postpartum depression. 4. Describe the features of bipolar disorder and cyclothymic disorder and distinguish between them. 5. Discuss the relationship between stress and mood disorders. 6. Discuss the psychodynamic, humanistic, learning, cognitive, and biological perspectives on the origins and treatment of mood disorders. 7. Discuss the incidence of suicide and theoretical perspectives on its causes. Chapter Outline I. Types of Mood Disorders A. B. C. D. Major Depressive Disorder Dysthymic Disorder Bipolar Disorder Cyclothymic Disorder II. Causal Factors in Depressive Disorders A. B. C. D. E. F. G. Stress and Depression Psychodynamic Theories Humanistic Theories Learning Theories Cognitive Theories Learned Helplessness (Attributional) Theory Biological Factors III. Causal Factors in Bipolar Disorders IV. Treatment of Mood Disorders A. Treating Depression B. Treating Bipolar Disorder 93 V. Suicide A. B. C. D. Who Commits Suicide? Why Do People Commit Suicide? Theoretical Perspectives on Suicide Predicting Suicide VI. Summing Up Chapter Overview Types of Mood Disorders Mood disorders are disturbances in mood that are serious enough to impair daily functioning. There are various kinds of mood disorders, including depressive (unipolar) disorders, such as major depression and dysthymic disorder, and disorders involving mood swings, such as bipolar disorder and cyclothymic disorder. People with major depressive disorder experience profound changes in mood that impair their ability to function. There are many associated features of major depression, including depressed mood, changes in appetite, difficulty sleeping, reduced sense of pleasure in formerly enjoyable activities, feelings of fatigue or loss of energy, sense of worthlessness, excessive or misplaced guilt, difficulties concentrating, thinking clearly or making decisions, repeated thoughts of death or suicide, attempts at suicide, or even psychotic behaviors (hallucinations and delusions). About twice as many women as men seem to be affected by major depression, but the reasons for this gender difference remain unclear. Depression can begin or recur at any age, but the risk of initial onset of depression is age related. Major depression has been increasing worldwide. Dysthymic disorder is a form of chronic depression that is milder than major depression but may, nevertheless, be associated with impaired functioning in social and occupational roles. There are two general types of bipolar disorders: bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder. Bipolar I disorder is identified by the occurrence of one or more manic episodes, which generally, but not necessarily, occur in persons who have experienced major depressive episodes. In bipolar II disorder, depressive episodes occur along with hypomanic episodes, but without the occurrence of full-blown manic episodes. Manic episodes are characterized by sudden elevation or expansion of mood and sense of self-importance, feelings of almost boundless energy, hyperactivity, and extreme sociability, which often takes a demanding and overbearing form. People in manic episodes tend to exhibit pressured or rapid speech, rapid "flight of ideas," and decreased need for sleep. Cyclothymic disorder is a type of bipolar disorder characterized by a chronic pattern of mild mood swings and sometimes progresses to bipolar disorder. 94 Theoretical Perspectives In classic psychodynamic theory, depression is viewed in terms of inward-directed anger. People who hold strongly ambivalent feelings toward people they have lost, or whose loss is threatened, may direct unresolved anger toward the inward representations of these people they have incorporated or introjected within themselves, producing self-loathing and depression. Bipolar disorder is understood within psychodynamic theory in terms of the shifting balances between the ego and superego. More recent psychodynamic models, such as the self-focusing model, incorporate both psychodynamic and cognitive aspects in explaining depression in terms of the continued pursuit of lost love objects or goals that would be more adaptive to surrender. In the humanistic framework, feelings of depression reflect the lack of meaning and authenticity in the person's life. Learning perspectives focus on situational factors in explaining depression, such as changes in the level of reinforcement. When reinforcement is reduced, the person may feel unmotivated and depressed, which can lead to inactivity and further reduction in opportunities for reinforcement. Coyne's interactional theory focuses on the negative family interactions that can lead family members of depressed people to become less reinforcing to them. Beck's cognitive theory focuses on the role of negative or distorted thinking in depression. Depression-prone people hold negative beliefs toward themselves, the environment, and the future. This cognitive triad of depression leads to specific errors in thinking, or cognitive distortions, in response to negative events, that in turn, lead to depression. The learned helplessness model is based on the belief that people may become depressed when they come to view themselves as helpless to control the reinforcements in the environment or to change their lives for the better. A reformulated version of the theory held that the ways in which people explain events – their attributions – determine their proneness toward depression in the face of negative events. The combination of internal, global, and stable attributions for negative events renders one most vulnerable to depression. Genetics appears to play a role in mood disorders, especially in explaining major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Imbalances in the neurotransmitter activity in the brain appear to be involved in depression and mania. The diathesis-stress model is used as an explanatory framework to illustrate how biological or psychological diatheses may interact with stress in the development of depression. Treatment of Mood Disorders Psychodynamic treatment of depression has traditionally focused on helping the depressed person uncover and work through ambivalent feelings toward the lost object, thereby lessening the anger directed inward. Modern psychodynamic approaches tend to be more direct and briefer and focus on developing more adaptive means of achieving self-worth and resolving interpersonal conflicts. 95 Learning theory approaches have focused on helping people with depression increase the frequency of reinforcement in their lives through such means as increasing the rates of pleasant activities in which they participate and assisting them in developing more effective social skills to increase their ability to obtain social reinforcements from others. Cognitive therapists focus on helping depressed people identify and correct distorted or dysfunctional thoughts and learn more adaptive behaviors. Biological approaches have focused on the use of antidepressant drugs and other biological treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Antidepressant drugs appear to increase the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain. Bipolar disorder is commonly treated with lithium. Suicide Mood disorders are often linked to suicide. Although women are more likely to attempt suicide, more men actually succeed, probably because they select more lethal means. The elderly, not the young, are more likely to commit suicide, and the rate of suicide among the elderly appears to be increasing. People who attempt suicide are often depressed, but they are generally in touch with reality. They may, however, lack effective problem-solving skills and see no way to deal with their life stress other than suicide. Lecture and Discussion Suggestions 1. Interpersonal aspects of depression. Our interactions with others may be an important factor in the onset and management of depression. Especially helpful here is James Coyne's interactional theory, described in this chapter. According to this view, people who are depressed affect and are affected by their interactions with loved ones. Basically, Coyne holds that living with a depressed person can become so stressful that this person's partner or family become less supportive over time toward the depressed person. Initially the depressed person may succeed in eliciting support from others. However, over time, the depressed person's demands evoke feelings of annoyance, anger, and eventually aversive reactions. The depressed person may then react to rejection by becoming more demanding, which results in further rejection and withdrawal of positive reinforcement in vicious cycles. Consequently, the depressed person becomes more depressed and family members living with the person also experience higher stress and depression. Coyne found that as many as 40 percent of family members of depressed people were sufficiently depressed as to need therapeutic intervention; however, there may be other contributing factors such as genetic and environmental overlap as well as selection-bias in choosing friends and mates. This theory has important implications for managing depression, including modifying the depressed person's demands for support and helping family members to sustain realistic but helpful levels of reinforcement. 96 2. Beck's cognitive approach to depression. Aaron Beck's cognitive theory of depression holds that people who adopt a habitual style of negative thinking are more likely to become depressed. The cognitive triad of depression, described in this chapter, involves the adoption of negative thinking about oneself ("I'm no good"), the environment ("school is awful"), and the future ("nothing will ever turn out right for me"). Early learning experiences are believed to play a major role in shaping these negative attitudes. Once adopted, however, such habitual negative thinking is manifested in "automatic thoughts," or cognitive distortions, such as all or nothing thinking, overgeneralization, and disqualifying the positive. These spontaneous cognitive distortions then sensitize people to interpret any disappointment or failure as a total defeat, which then leads to depression. Therapeutic intervention includes helping depressed persons to identify their particular pattern of cognitive distortions and modify them accordingly. Drs. Aaron and Judith Beck have several training videos on using cognitive behavioral therapy to treat depression. Discuss Dr. Beck’s theory while interspersing video segments that demonstrate key aspects of the treatment protocol, how it links to Dr. Beck’s theory, and why it is effective in treating symptoms of depression. 3. Exercise and depression. Many studies have shown a link between regular physical exercise and the alleviation of depression. People who exercise regularly are less depressed. But, it works the other way too, so that people who are more depressed simply exercise less. In order to demonstrate a causal link between exercise and depression, Lisa McCann and David Holmes ("Influence of aerobic exercise on depression," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1984, 46, p. 1142-1147) performed an experiment with college women at the University of Kansas. Students were randomly assigned, either to an exercise group, involving running and aerobic exercise, or to a control group, which involved no exercise. Results showed that only the students in the exercise group became markedly less depressed, but it is not clear how or why exercise alleviates depression. Some explanations focus on the changes in body and brain chemistry, such as the rising levels of endorphins in the blood during exercise. Other explanations stress the sense of mastery over one's body gained through exercise, which may also contribute to a greater sense of personal control over other aspects of one's life. In a recent exploration of the link between depression and exercise, Drs. Ruth L. Hall and Carole A. Oglesby find support for the benefit of integrating exercise, sports, and therapy in treating women with depression in their book, Exercise and Sport in Feminist Therapy: Constructing Modalities and Assessing Outcomes (2003; The Haworth Press, Inc. and a monograph published simultaneously as Women & Therapy, Vol. 25, No. 2.) 4. Getting rid of "the blues." Ask students what they do to get rid of "the blues." Everyone has an occasional "down" day. Ask students to share their strategies for shaking off such moods. How successful are these strategies? How many of the activities they describe are listed in the Pleasant Events Schedule in the text? How can they tell "the blues" from a more serious depression? 97 5. Depression and politics. Invite students to discuss their feelings about having a presidential or vice presidential candidate who has been treated for depression. When there was a public disclosure that Senator Thomas Eagleton, a democratic candidate for vice president in the 1972 election, had been given electroconvulsive for depression, his name was reluctantly withdrawn due to the uproar that followed the disclosure. Was Eagleton treated fairly? Should we make treatment available and then effectively punish public figures who choose to get treated? Does suffering from a mood disorder or other mental illness once mean that one is never qualified for public office thereafter? 6. Postpartum depression. Postpartum mood changes attendant upon childbirth can reach the level of depression and even psychosis in some women. In these situations the woman can present a danger to herself as well as her newborn child. Invite students to analyze postpartum depression according to the major perspectives presented in the text: psychodynamic, learning, cognitive, interactional, humanistic existential, and biological. For example: Is the new mother re-experiencing unresolved childhood conflicts? Has she learned that some reinforcers are contingent upon the role of depressed person? Are certain distorted cognitions playing a part in her disorder? Or, is it primarily a result of hormonal changes that occur after childbirth? How might postpartum depression be viewed from the interactional perspective? 7. Depression and children. The Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1992, 31) devotes several articles to various aspects of the occurrence of mood disorders in children and adolescents. Of special interest is an article by Weissman, Fendrich, Warner, and Wickramaratne titled "Incidence of Psychiatric Disorder in Offspring at High and Low Risk for Depression." Of the 174 children in the study, 121 were offspring of 1 or more depressed parents. In a 2-year longitudinal study, first onsets of suicide attempts and psychiatric disorders in these children were determined. Of the children of depressed parents, 7.8 percent reported making at least one suicide attempt in their lives, while 1.4 percent of non-depressed parents' children made an attempt. All of the cases of major depression (10) and anxiety disorder (8) occurred in children of depressed parents. Incidence of substance abuse did not differ for the two groups. Conduct disorder rates were higher among the children of depressed parents, but not significantly so. The cumulative probability by age 20 for the children of depressed parents that they will report having a major depression is over 50 percent. 98 What implications can students draw from these results about the occurrence of mood disorders in children? Would periodic assessment of children at some risk for depression due to their parents' depression be ethical? The federal law mandating early childhood intervention for children at risk, PL 99-457, makes provision for family-centered and family-sensitive assessment for children at risk for many disorders. Do students feel that a case could be made for early intervention and assessment for something like depression? What could go wrong with an effort at massive intervention like this? 8. Gender and depression. There have been many different explanations for the higher incidents of depression in women versus men. Susan Nolen Hoeksema (1987) offers an excellent review of these theories, and then offers her own. She believes that we all get depressed at times, but that the genders react to these depressions in different ways. Men try to distract themselves, such as by playing a sport, taking drugs, or doing physical work. Women, on the other hand, are less active in their response. They ruminate more about the causes of their depression. NolenHoeksema believes it is this rumination that leads to helpless feelings, remembering of sad things, and self-blame. This tendency to think and ruminate is possibly socialized early in life. This theory suggests that women might respond to depression by engaging in pleasant activities and other (non-drug taking) distractions as a way to fight the mild depressions we all experience. Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1987) "Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory." Psychological Bulletin, 101, 259-282. 9. Suicide on TV. Many studies suggest that suicide rates increase following depiction of suicide in the media. These findings have raised public concern about imitation effects. We might hypothesize that youths would be particularly prone to such effect, and indeed, some research has demonstrated an increase in imitative youth suicides following both news stories of suicide and television movies about suicide. However, more recent evidence raises doubt about the suggested negative effects of depicting suicide on TV. Berman (American Journal of Psychiatry, 1988, 145, 982-986) reviewed research on youth suicide following made-for-television movies depicting suicide, and conducted a study to improve methodological problems identified in previous research. The re-analysis found a significant decrease in the number of suicides following the broadcast of three films depicting suicide in 1985 and 1986. The decrease was nonsignificant for those age 24 or younger. However, the findings suggested that films which depict a specific method of committing suicide may result in selection of that method over other methods in subsequent suicides. The authors conclude that a complex interplay of the person, the stimulus, and the environment affect the impact of media suicide, and further suggest that beneficial effects of the depiction of suicide cannot be ruled out. Show the PBS film, The Silent Epidemic: Teen Suicide, and discuss factors unique to teens and suicide. Given the proximity in age between high school and many college students, ask them to comment on the fear of imitation effects and copycat suicides. 99 10. Is depression contagious? What is it like to be around depressed people? Many experts believe it exacts a toll on families of those seriously depressed. James Coyne's interactional theory is concerned with this effect. In an early, study he had college students talk on the phone to a seriously depressed person who was under treatment for that problem. After only a few minutes, the students experienced various negative feelings, including depression, anxiety, and hostility. In a later study, students spoke to a person who was only mildly depressed. Nevertheless, the conversation provoked the same negative feelings reported in the first study. Along with the lower mood, subjects in these studies also tended to devalue or reject the depressed people they talked to. All of this suggests that depression and social rejection is a two-way street. Sometimes being rejected is depressing; other times being depressed induces rejection by depressing others. As Coyne suggests, depression is not just a problem within the person who has it. It elicits social reaction, which, in turn, can aggravate the depression. Solicit your student's reactions to Coyne's idea. Does it fit with their experiences? Coyne, J. C., Kessler, R. C., Tal, M., Turnball, J., Wortman, C. B., & Greden, J. F. (1987). "Living with a depressed person." Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 347-352. 11. Are anxiety and depression the same thing? Now that you have covered both anxiety and mood disorders, it is useful to remind the class how similar these are. For instance, tests of anxiety and depression typically correlate moderately to strongly with each other. How are depression and anxiety alike or different? Leanna Clark and David Watson are among those who cite the broad personality dimensions of positive affectivity (PA) and negative affectivity (NA) as explanatory factors. PA is the tendency to experience positive moods, such as feeling cheerful or proud. NA is the tendency to experience anxiety, anger, and other negative moods. Each of us differs in the relative levels of these two tendencies, and PA and NA are uncorrelated across people. Clark and Watson believe that high NA characterizes both anxiety and depression. This no doubt accounts for the high intercorrelation of tests of those two constructs. The difference comes in that depression is related to low levels of PA, while anxiety is not. Anxiety is marked more by physiological arousal rather than low PA. This is seen in the clinical world, where many patients seem to have an equal mix of anxiety and depression, while others have a high degree of one and at least some of the other. So, anxiety and depression are alike, but they are also different. Clark, L. A. & Watson, D. (1991). "Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications." Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 316-336. 100 12. Warning signs of suicide. Discuss the warning signs of suicide. Some of the classic signs of suicide are expression of suicidal thoughts, prior suicide attempts, giving away prized possessions, intense depression over broken relationships, despair over a chronic illness or problem, change in eating or sleeping habits, marked personality change, abuse or increased abuse, of alcohol or drugs, a sense of helplessness and hopelessness, veiled warnings or hints that the person might not be around much longer, and increased withdrawal and isolation. In discussing this, you should also discuss with students what to do if they see the warning signs in a friend or loved one and suspect that the person is thinking about attempting suicide. The "A Closer Look: Suicide Prevention" box in this chapter provides a good basic outline of the things to do when faced with such a situation. 13. Suicide and its effects. The effects of suicide on those in a relationship with the person who dies are complex, involving both pain and anger. Brent and colleagues interviewed 58 adolescent friends and acquaintances of 10 adolescent suicide victims six months after their deaths. The study found that exposure to suicide was "clearly associated with significant psychiatric sequelae, namely major depression and symptoms of PTSD (p. 636)." The evidence showed no imitation of suicidal behavior. In fact, suicides seemed to act to make the friends less inclined to it. The most common sequela was major depression, which was found to be correlated with severity of grief. The depression and grief were both correlated with closeness of relationship to the victim. Brent, D. A., Perper, J., Moritz, G., Allman, C., Friend, A., Schweers, J., Roth, C., Balach, L., & Harrington, K. (1992). "Psychiatric effects of exposure to suicide among the friends and acquaintances of adolescent suicide victims.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 629-640. 14. Clinical, ethical, and philosophical issues in handling suicide. The topic of suicide is likely to raise personal issues in any classroom; the odds are that at least one person in an average class has had a personal experience with a friend or relative attempting or committing suicide, or perhaps personally grappling with suicidal ideas. In regards to discussion topic #2 (above), you might point out that psychiatrist Thomas Szasz views suicide as a fundamental right, in a manner not too different philosophically from the position claimed by Dr. Jack Kervorkian. Szasz believes that responsibility for a decision to commit suicide rests squarely in the hands of the patient, not the therapist or caregiver. He opposes the use of coercive means in preventing suicide in adults. While Szasz has not gone so far as Dr. Kervorkian to the point of actually assisting in a patient's suicide attempt, he stakes out philosophical ground that is only one step away from such action. Ask students what they think of Szasz's and Kervorkian's ideas and actions. What are the pros and cons of our current laws and ethical rules regarding suicide? What are the pros and cons of Szasz's approach or Kervorkian's approach? Talk about Kervorkian’s conviction and recent release from prison for his actions? What responsibilities do mental health professionals have in preventing suicide? Can they ethically support a "pro-suicide" position? 101 Think About It How do clinicians distinguish between normal variations in mood and mood disorders? Feeling down or depressed is not abnormal in the context of depressing events or circumstances. But, people with mood disorders experience disturbances in mood that are unusually severe or prolonged and impair their ability to function in meeting their normal responsibilities. Some people become severely depressed even when things seem to be going well. Still others experience extreme mood swings from incredible highs to abysmal lows. For most of us, mood changes pass quickly or are not severe enough to interfere with our lifestyle or ability to function. People with mood disorders have mood changes that are more severe or prolonged and affect daily functioning. “Women are just naturally more inclined to depression than men.” Do you agree or disagree? Explain your answer. Students should be familiar with gender differences in the incidence and prevalence rates of depression. Encourage them to 1) maintain a skeptical attitude, 2) consider the definitions of the terms, 3) weigh the assumptions or promises on which arguments are based, 4) bear in mind that correlation is not causation, 5) consider the kinds of evidence on which conclusions are based, 6) do not oversimplify, 7) do not over generalize. Why is it difficult to distinguish between cyclothymic and bipolar disorder? Cyclothymia and bipolar disorders are similar in that both involve abnormal mood swings. The boundaries between bipolar and cyclothymic disorder are not clearly established. Some forms of cyclothymic disorder may represent a mild, early type of bipolar disorder. Approximately 33 percent of people with cyclothymic disorder eventually develop bipolar disorder. We presently lack the ability to distinguish between people with cyclothymia who are likely to eventually develop bipolar disorder. Which of the cognitive distortions, if any, that are listed in the text characterize your way of thinking about disappointing experiences in your life? What were the effects of these thought patterns on your mood? How did they affect your feelings about yourself? How might you change these ways of thinking in the future? This is a personal experience question. Students need to be familiar with the different cognitive distortions as outlined in the text. What evidence supports a genetic contribution to mood disorders? Is genetics solely responsible? Why or why not? Evidence has accumulated pointing to the important role of biological factors, especially genetics and neurotransmitter functioning, in the development of mood disorders. We know mood disorders, especially bipolar disorders, tend to run in families. Twin studies and adoptive studies contribute evidence to the idea of genetic contribution with high concordance rates. However, genetics isn’t the only determinant. Moreover, genetics may not be the most important determinant. Environmental factors, such as exposure to stressful life events, appear to play at least as great a role – if not a greater role – than genetics. 102 Jonathan becomes clinically depressed after losing his job and his girlfriend. Based on your review of the different theoretical perspectives on depression, explain how these losses may have figured in Jonathan’s depression. Depression and other mood disorders involve the interplay of multiple factors. Consistent with the diathesis-stress model, depression may reflect an interaction of biological factors, psychological factors, and social/environmental stressors. In Jonathan’s case, certainly environmental and social factors come into play with the loss of both his girlfriend and job. He may be biologically at risk for depression from his family background. Certainly genetics and brain chemistry can be a factor. Finally, Jonathan may be psychologically at risk. If he engages in cognitive distortions or has a sense of learned helplessness, depression can occur. If you were to become clinically depressed, which course of treatment would you prefer-medication, psychotherapy, or a combination? This is a personal opinion question. Students need to know the different treatments available and the pros and cons of each. End with an emphasis on the effectiveness of combining both medication and psychotherapy for stable longterm improvement. What factors are related to suicide and suicide prevention? Did your reading of the text change your ideas about how you might deal with a suicidal threat by a friend or loved one? If so, how? This is a personal experience question. Students should know the facts relating to suicide and suicide prevention. Activities/Demonstrations 1. Cognitive distortions. Ask students to select approximately six negative thoughts they engage in from time to time. If they find it difficult to recall any, have them choose some representative thoughts listed in table 8.5 in the text. Once they have chosen some characteristic negative thoughts, have them identify the kind of cognitive distortion each thought represents along with a rational response (see below). Automatic Thought Cognitive Distortion Rational Response "I rarely succeed at anything" Overgeneralization "Sometimes I succeed, sometimes I don't" You might have students write a brief one-page reaction paper, telling what they have learned from doing this exercise and how they can utilize these strategies in the future. 2. The “Are You Depressed?” Scale. Have students fill out the “Are you Depressed?” scale in the text. Since students with high scores may feel embarrassed about revealing their scores, you might have them write their scores anonymously on a slip of paper and collect the slips from them. Scan through the slips and see what the scores are. Often, the scores will average much higher than students might expect. This can lead to a discussion of what types of things are causing depression among students and what are the various ways they can cope or get help. 103 Video Resources Prentice Hall Videos ABC News/PH-Library #1: New Mother's Nightmare (20/20, 8/2/91, 15:31). Explores the prevalence and effects of postpartum depression on mothers of newborns. ABC News/Ph-Library #1: Desperate for Light (ABC News Series, 1988, 11 min.). Describes cases of seasonal affective disorder. ABC News/PH-Library #1: Depression: Beyond the Darkness (ABC News Series, 47 min.). Describes several cases of clinical depression and treatment approaches, including talk therapy, antidepressant medication, and ECT . ABC News/PH-Library # 2: The Only Way Out -- Teen Suicide in NH Town (Day One, 2/28/94). Explores the causes and effects of five teen suicides in the town of Goffstown, New Hampshire. ABC News/PH-Library #2: American Agenda -- Prozac (World News Tonight with Peter Jennings, 1/4/94). Explores problems related to the over prescription of Prozac. ABC News/PH-Library #2: Beating Depression (Nightline, 3/17/94). Case study of how ABC News Washington bureau chief George Watson was treated for depression. Patients as Educators, Case #3 -- Helen, Major Depression (14:05). Case study of an 83-year-old female who has suffered depression since childhood and who still keeps a potentially lethal supply of sleeping capsules with her. Other Videos Beck's Cognitive Therapy, Part of the "Three Approaches to Psychotherapy" series, 42 min. color (Psychological Films, Inc.). Aaron Beck explains and demonstrates his cognitive therapy with a depressed client. Biochemistry of Depression, 29 min. color (CM). Presents a wide range of technical material relating to the biochemical underpinnings of depression. Depression, 19 min. color (Films for the Humanities and Sciences). Explains the difference between occasional and realistically motivated mood changes and depression. Depression, 59 min. color (Kent State Univ.). Follows the lives of people suffering from depression or bipolar disorder, and includes a discussion of the causes of depression and suicide risks. 104 Depression: A Study in Abnormal Behavior, 26 min. color (CRM/McGraw-Hill Films). Follows a young teacher and homemaker through her depression and includes various approaches to treatment, including hospitalization. Depression: Biology of the Blues, 26 min. color (Films for the Humanities and Sciences). Focuses on the biological causes of depression. Depression: Recognizing It and Treating It, 42 min. color (Human Relations Media). An overview of the treatment of depression, including psychodynamic, cognitive, and biochemical approaches. Depression: The Shadowed Valley, 57 min. color (IU). An overview of the various forms of depression, including suicide as the extreme form, and various treatment approaches. Depression and Suicide: You Can Turn Bad Feelings into Good Ones, 26 min. color (PCR). Explores some of the causes of depression in teenagers and ways to prevent feelings related to depression from becoming overwhelming. Do I Really Want to Die? 31 min. color (Polymorph Films). Shows a series of interviews with people who have attempted suicide. Dying to be Heard: Is Anybody Listening? 25 min. color (Films for the Humanities and Sciences). Offers specific advice on how to recognize suicide warning signs in teens and how to intervene successfully. Gifted Adolescents and Suicide, 26 min. color (Films for the Humanities and Sciences). Specially adapted Phil Donahue program focusing on two couples who lost gifted 17-year-old children to suicide. Grief Therapy, 19 min. color (Carousel Films). A therapeutic interview with a woman who lost her mother and daughter in a fire. Mysteries of the Mind, 58 min. color (Films for the Humanities and Sciences). Explores bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcoholism, and related mood disorders. On Death and Dying, 40 min. color (FI). Elizabeth Kübler-Ross discusses the stages of death and dying and how the process can be made more humane. One Man's Madness, 31 min. color (BBC). Documentary of a writer who developed bipolar disorder. Shows extreme symptoms and treatment in the hospital. Psychopathology: Diagnostic Vignettes: No. 1, Dysthymic Disorder and Major Affective Disorder, 38 min. color (IU). Shows a group of depressed patients with characteristic symptoms of these disorders. 105 The Secret Life of the Brain Part IV. The Adult Brain: To Think by Feeling, 60 min. (PBS). This film explores the brain as the center of both intellect and emotion, and this episode chronicles the critical balance between these processes and explores what happens when the balance is lost. Scientists draw insight from the stories of a stroke victim and a sufferer of posttraumatic stress disorder, and break new ground in the struggle to understand and treat depression. The Silent Epidemic: Teen Suicide, 30 min. (PBS). This film is part talk show and part docu-drama, focusing on the epidemic of teenage suicide and depression. The film profiles teens who have attempted suicide and their progression in coping with depression. Grammy-award winning recording artist CeCe Winans hosts a studio audience segment in which teens and suicide experts discuss warning signs, causes, and prevention of teen suicide. Serious Depression, 28 min. color (Films for the Humanities and Sciences). Explains that women are at higher risk for depression than men and interviews experts on the causes and treatment of depression. Suicide Survivors, 26 min. color (Films for the Humanities and Sciences). Explores the special needs of suicide survivors. Trouble in Mind: Postpartum Depression, 30 min. (Unapix/Ardustry Film; 2000). This film is part of a series that looks at various mental disorders and treatments for them. This episode on postpartum depression examines the changes in a woman's body during pregnancy, birth, and the initial adjustment to motherhood, the associated stress, and hormonal changes that contribute to this condition. It also discusses innovative treatments to help mothers and newborns after delivery. Narrated by Jaclyn Smith. Speaking Out Videos in Abnormal Psychology CD ROM 6 - Everett: Major Depression VIDEO BACKGROUND: In this interview, Everett talks about the major depression he has experienced since childhood. Beginning at the age of two, Everett explains how his depression has affected many important areas of his life: he had difficulties with relationships, low self-esteem, poor occupational functioning, etc. To deal with his illness, Everett began self-medicating with prescription drugs as well as alcohol and eventually tried to commit suicide. He was reluctant to be hospitalized fearing stigma, but eventually spent more than six months in a hospital. Now he feels he has turned his life around and is working to “tear down the walls” he built in his relationships during the first 48 years of his life. A particularly interesting segment is his discussion of how one feels during a Depressive Episode. 106 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: 1. Major Depression can begin: a) during childhood b) during adolescence c) during adulthood d) all of the above Answer: d. Although major depression is often thought of as an “adult’s disease,” it can begin at any age. As Everett notes, when he was younger, childhood depression may have been an uncommon diagnosis. Now childhood depression is more regularly recognized and diagnosed. 2. Which of the following would rule out a diagnosis of major depression? a) psychotic features (i.e., hallucinations, delusions) b) catatonia c) mania d) insomnia Answer: c. Psychotic features and catatonia are both included in the subtypes of major depression. Insomnia can be a symptom of the required major depression episode. The presence of a non-drug induced manic episode, however, prevents a diagnosis of major depression. 3. Which of the following is NOT a diagnostic symptom of major depression? a) diminished interest in activities b) weight loss c) weight gain d) irritability Answer: d. Although one might associate irritability with depressed people, it is not a diagnostic feature of a major depressive episode. Note that both weight loss and gain are diagnostic features. 4. Everett discusses some of the cognitions associated with depression in this video. What kind of thoughts do people with depression commonly have? Suggested answers: suicide, death, worthlessness, guilt, etc. In addition, their thoughts tend to be negative and pessimistic in regards to the self, the world, and the future. 5. Everett discussed the ways his depression affected his life. List some of the effected areas and the way in which they were affected. Suggested answers: occupationally, feeling he was the “world’s worst teacher” and “world’s worst principal”; relationships, feeling like a bad father/spouse; self-esteem, feelings of worthlessness, etc. 107 CLASS ACTIVITY: 1. Although depression itself can be very difficult to overcome, often people continue to have problems after their depression is in remission. Discuss depression-related problems people might have after they feel they have overcome their depression. Suggested answers: difficulty mending relationships, difficulty finding a job, problems reorganizing life, etc. 7 - Sarah: Depression/Deliberate Self-Harm VIDEO BACKGROUND: In this interview, Sarah discusses her early-onset depression stemming from her living situations and abuse. The depression has affected her life in numerous areas including school functioning and relationships; it has also led her to deliberate self-harm (cutting) as a coping mechanism. She has moved from place to place and has been in foster care for some time. She experiences low levels of trust for others as well as suicidal ideation and has been hospitalized for months. In addition, she has symptoms of insomnia and irritability, which often are present during depressive episodes. Sarah’s discussion of why she cuts and how it makes her feel during and after are of particular interest. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: 1. In the discussion of her cutting behavior, Sarah notes that it makes her feel: a) scared b) pain c) relief d) anxiety Answer: c. Although it is natural to have fear and avoidance reactions to being cut, people who self-harm do so as a coping mechanism and therefore seek relief. 2. Deliberate self-harm is also associated with: a) Obsessive/Compulsive Disorder b) Borderline Personality Disorder c) Schizophrenia d) all of the above Answer: b. People with borderline personality disorder sometimes use self-harm to prevent others from abandoning them, while self-harm behavior is not associated with OCD or schizophrenia. 3. Sarah discusses her cutting in detail during this interview. What seems to be the purpose of her cutting? Suggested answers: relief, release of negative feelings, coping with depression, relaxation, control, escape, etc. 4. What are some possible reasons someone would turn to deliberate self-harm? Suggested answers: control, a “reality check,” familiarity, dissociation, endorphin release, sense of escape, etc. 108 CLASS ACTIVITIES: 1. It seems that cutting has become more popular in recent years. What are some reasons for this? Suggested answers: increased media attention, increased knowledge of cutting as a “coping option,” peer pressure, etc. 2. People cope with depression in various ways. Discuss some other ways, both positive and negative, that people cope with depression. Suggested answers: self-medication, alcohol, drugs, suicide, violent behavior, seeking psychotherapy, seeking pharmacological interventions, etc. 8 - Ann: Bipolar Mood Disorder with Psychotic Features VIDEO BACKGROUND: In this interview, Ann discusses how her bipolar mood disorder has affected her life in multiple ways. Although she has had only one major depressive episode, Ann’s Manic Episodes have led to significant difficulties including the loss of her marriage, job, friends, and custody of her daughter. She also experienced delusions throughout the course of her disorder, including beliefs that she was in line for the presidency of Harvard or MIT, that her mother was disguised as Che Guevara on television, and that the CIA was going to assassinate her. These delusions led to paranoia and alcohol abuse. Ann currently receives psychotherapy and medication and attends self-help groups. She “runs light” on her medications so she can remain in a hypomanic state at all times. Interesting segments include her discussion of how one feels during a manic episode and the perceived benefits of being manic. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: 1. What symptom is most associated with bipolar I disorder? a) mania b) depression c) psychosis d) insomnia Answer: a. A diagnosis of bipolar I disorder requires either a manic or mixed episode. Depressive episodes are very common as well, however. Psychosis and/or insomnia may appear as well, but are not required for diagnosis. 2. What disorder might a clinician most want to rule out to determine a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder? a) Schizophrenia b) Schizoaffective Disorder c) Schizoid Personality Disorder d) Schizotypal Personality Disorder Answer: b. As bipolar I disorder is a mood disorder, it would be most important to rule out disorders involving a mood component. Although the other disorders listed might involve comorbid mood disturbances, only schizoaffective disorder requires mood symptoms. 109 3. What are some ways in which mania has negatively affected Ann’s life? Suggested answers: loss of job/relationships, insomnia, racing thoughts, tension, etc. 4. What are some ways in which Ann feels mania affected her life positively? Suggested answers: high energy, ability to see connections in business, creativity, etc. 5. How does Bipolar Disorder I differ from Bipolar Disorder II? Answer: Bipolar Disorder I requires at least one Manic Episode or Mixed Episode. Bipolar Disorder II requires at least one Major Depressive Episode and at least one Hypomanic Episode. CLASS ACTIVITY: 1. Although not all people with Bipolar I Disorder have a wide range of symptoms, Ann’s symptomatology was multifaceted. Discuss the symptoms Ann had and put them into diagnostic groups. Suggested answers: MANIC SYMPTOMS: energy, hyperactivity, substance use, etc.; DEPRESSED SYMPTOMS: sadness, etc.; PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS: delusions (e.g., thinking her office was bugged, thinking she was in line for university presidencies), etc. 110