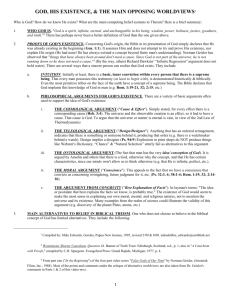

PURE_Front_Matter_Introduction_and_Chpater_5

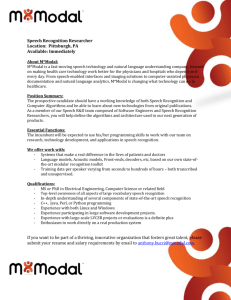

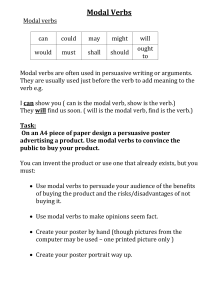

advertisement