View/Open

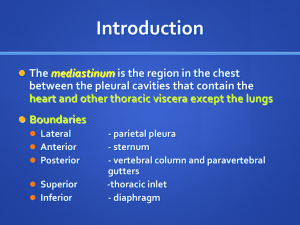

advertisement

Word count text : 2634. Word count abstract : 225. Endosonography for mediastinal nodal staging of clinical N1 nonsmall cell lung cancer : a prospective multicenter study. Christophe Dooms, PhD1*; Kurt G. Tournoy, PhD2*; Olga Schuurbiers, PhD3; Herbert Decaluwe, MD4; Frédéric De Ryck, MD5; Ad Verhagen, MD6; Roel Beelen, MD7; Erik van der Heijden, PhD3; Paul De Leyn, PhD4. 1 Respiratory Division, University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium. 2 Department of Pneumology, University Hospital Ghent and OLV Ziekenhuis Aalst, Belgium. 3 Department of Pulmonary Disease, Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen, The Netherlands. 4 Department of Thoracic Surgery, University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium. 5 Department of Thoracic Surgery, University Hospital Ghent, Belgium. 6 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen, The Netherlands. 7 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, OLV Ziekenhuis Aalst, Belgium. * These authors equally contributed to this manuscript. Summary conflict of interest statement : none for all authors. Funding source : none. Corresponding author: Christophe Dooms, MD, PhD, Respiratory Division, University Hospitals Leuven, Herestraat 49, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium e-mail : christophe.dooms@uzleuven.be 1 Abstract. Background: Patients with clinical N1 (cN1) lung cancer based on imaging are at risk for malignant mediastinal nodal involvement (N2-disease). Endosonography with a needle technique is suggested over surgical staging as a best first test for preoperative invasive mediastinal staging. The addition of a confirmatory mediastinoscopy seems questionable in patients with a normal mediastinum on imaging. This prospective multicenter trial investigated the sensitivity of preoperative linear endosonography and mediastinoscopy for mediastinal nodal staging of cN1 lung cancer. Methods: Consecutive patients with operable and resectable cN1 non-small cell lung cancer underwent a lobe-specific mediastinal nodal staging by endosonography. The primary study outcome was sensitivity to detect N2-disease. The secondary endpoints were the prevalence of N2-disease, the negative predictive value (NPV) of both endosonography and endosonography with confirmatory mediastinoscopy, and the number of patients needed to detect one additional N2-disease with mediastinoscopy. Results: Of the 100 patients with cN1 on imaging, 24 patients were diagnosed with N2disease. Invasive mediastinal nodal staging with endosonography alone has a sensitivity of 38%, which can be increased to 73% by adding a mediastinoscopy. Its NPV was 81% and 91%, respectively. Ten mediastinoscopies are needed to detect one additional N2disease missed by endosonography. Conclusions: Endosonography alone has an unsatisfactory sensitivity to detect mediastinal nodal metastasis in cN1 lung cancer, and the addition of a confirmatory mediastinoscopy is of added value. [clinicaltrials.gov NCT01456429] 2 Introduction. Patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) presenting with enlarged or FDG-avid hilar lymph nodes (cN1) have a considerable risk to have malignant mediastinal nodal disease (N2-disease). N2-disease has been documented in 19-30% of cN1 lung cancer, despite a normal appearance of mediastinal lymph nodes on CT alone or integrated PET/CT.1-4 Therefore, invasive mediastinal nodal staging before resection is strongly recommended over staging by imaging alone in patients with cN1 on integrated PET/CT.5-6 The recently updated recommendations on the staging of lung cancer have redefined the role of invasive mediastinal staging tools. A minimally invasive endosonography (endobronchial ultrasonography or combined endobronchial-esophageal ultrasonography) is suggested over surgical staging as a best first test for all lung cancer patients with any suspicion for mediastinal nodal disease.5-7 The recommendation to perform a confirmatory mediastinoscopy after a negative endosonography is solid for patients with suspect mediastinal nodes on imaging (i.e. discrete enlarged and/or 18F- fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) positive mediastinal nodes), but its clinical benefit for patients with a normal mediastinum on imaging is a matter of debate.8-10 It has been suggested that proceeding directly to surgical resection might be justified in case the preoperative endosonography is negative.10 However, patients with cN1 only represent a minority (<10%) in the controlled studies on which this suggestion is based.11-12 We therefore investigated the sensitivity of linear endosonography and mediastinoscopy to detect N2-disease in a large prospective multicenter trial dedicated to the patient with cN1 (without distant metastases) NSCLC by integrated PET/CT. Patient and methods. Patients with operable and resectable (suspected) NSCLC were eligible for the study if they had cN1 disease after an integrated whole-body PET/CT. The cN1 was based on either an enlarged hilar N1 lymph node on CT scan or visual FDG-uptake on PET in a hilar N1 lymph node. The FDG-uptake within the lymph node was compared to the 3 background FDG accumulation in the mediastinal vessel pool and reported positive whenever a FDG uptake higher than the background uptake in the mediastinal vessel pool was present. Patients with irresectable disease or with distant metastases were not eligible for this study. Only resectable clinical T stages T1, T2, and selected T3 (i.e. intraparenchymal tumor >7cm, T3 chest wall, or T3 additional nodule in the same lobe) were allowed. Exclusion criteria were CT enlarged or FDG-PET positive mediastinal lymph nodes, technical contraindication to endosonography or cervical mediastinoscopy, any centrally located primary tumor staged T3 or T4 by CT scan, or inability to consent. This investigator-initiated study was approved by the institutional review boards at the 3 participating hospitals (University Hospital Ghent, IRB 2010/014; University Hospitals Leuven, IRB S51974; Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen, IRB 2010/387), and registered as ASTER 2. The trial was registered (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01456429). All patients provided written informed consent. Endosonography. Endosonography of the mediastinum was performed using a dedicated convex probe ultrasound bronchoscope or combined convex probe ultrasound bronchoscope and esophageal endoscope. Transbronchial and esophageal procedures were performed during a single session by the same bronchoscopist in each center. The minimal requirement was to perform a lobe-specific mediastinal nodal examination using EBUS or combined EBUS-EUS. Therefore the requirement was to explore stations 2L-4L-7 in case of a left-sided upper lobe primary tumor, stations 4L-7-8-9 in case of a left-sided lower lobe primary tumor, or stations 2R-4R-7 in case of a right-sided primary tumor. Nodes larger than 5mm in short axis were sampled three times (in case no ROSE was available) or at least two times (in case ROSE was available) under real-time ultrasound guidance with a 22-gauge needle, labeled according to the IASLC lymph node map and sent for pathological examination. Cervical mediastinoscopy and surgical resection. Surgical staging was performed by cervical videomediastinoscopy according to current guidelines.13 A systematic assessment of left and right high and lower paratracheal and 4 subcarinal nodes was performed. Thoracotomy or VATS resection with systematic nodal dissection were performed according to current guidelines and considered the reference standard.14 Study design. A non-randomized prospective multicenter trial performing EBUS-TBNA or combined endosonography (EBUS-EUS) for mediastinal nodal staging of consecutive patients with operable and resectable NSCLC staged cT1-3N1M0 based on integrated PET/CT. End points. The primary endpoint was sensitivity to detect mediastinal nodal involvement (N2 disease) by linear endosonography (either EBUS or combined EBUS-EUS). Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of patients with N2 disease in whom the linear endosonography did show mediastinal nodal disease. Thoracotomy or VATS resection with nodal dissection was considered the reference standard for cases without N2 disease after preoperative mediastinal nodal staging. Secondary endpoints were: (1) the negative predictive value (NPV) and negative posttest probability for linear endosonography; (2) sensitivity, NPV and negative posttest probability for mediastinal nodal disease after both a negative endosonography and negative cervical mediastinoscopy; (3) comparison of sensitivity and NPV between the three participating centers; (4) the number needed to treat (NNT) as the number of patients needed to undergo a cervical mediastinoscopy to identify one case of mediastinal nodal disease missed by endosonography. Statistical analysis. Based on an incremental 25% sensitivity for endosonography compared to a sensitivity of 65% for surgical staging to detect N2 disease, we calculated a minimum sample size of 80 patients for a one proportion study group consisting of resectable cN1 lung cancer, having a prevalence for N2 disease of 20% (two-sided type I error of 5% and a power of 80%). A sample size of 100 patients was judged to be adequate to prove that a wellperformed linear endosonography enables the clinician to discard a confirmatory cervical mediastinoscopy. 5 For the primary analysis, sensitivity, NPV and negative posttest probability regarding mediastinal nodal status were calculated on an intention-to-treat basis for all included patients. For patients with missing reference standard, a multiple imputation analysis was performed. Imputation for missing values on mediastinoscopy or surgical resection was performed using a logistic regression model including primary tumor location, clinical T stage, clinical N1 station, clinical N1 short axis size, and center as predictor variables. In a secondary analysis, sensitivity, NPV and negative posttest probability were calculated on those patients for whom complete information on mediastinal nodal status was available. Differences between the three centers with respect to sensitivity and NPV are based on the multiple imputation data and tested using a logistic regression model. The probability of a positive mediastinoscopy after a negative endosonography for any given patient is calculated as the product of the probability of a positive surgery after a negative endosonography and the probability of a positive mediastinoscopy in case of a positive surgery. The NNT is the smallest integer that gives a value 1 when multiplied with the probability of a positive mediastinoscopy after a negative endosonography. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 of the SAS system for Windows (SAS Inc, Cary, NC, USA). All tests performed are two-sided and a 5% significance level is assumed for all tests. Two-sided 95% Wilson score confidence limits were given for sensitivity, NPV and negative posttest probability in cases of complete case analysis. Confidence limits and statistical tests based on multiple imputation data are based on the method of Rubin. Results. Between December 2009 and September 2013, 100 consecutive patients with operable and resectable (suspected) clinical N1 NSCLC were included (Figure 1). The clinical patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Endosonography procedure and the detection of nodal metastasis. The characteristics of the endosonography procedure are depicted in Table 2. At endosonography, a mean of 2.1 mediastinal nodal stations were biopsied. Endosonography was performed in all patients and detected mediastinal nodal 6 metastases in 10 patients (10%). Eighty-five patients without evidence of mediastinal nodal disease underwent surgical staging followed by resection or immediate resection, showing missed mediastinal nodal metastasis in 14 additional patients (Figure 1). These missed mediastinal metastases were single station N2 disease in 12 patients and multi-station N2 disease in 2 patients (Table 3). The missed mediastinal metastases were located in station 7 (n=5), station 4R (n=4), station 2R (n=1), station 4L (n=2), station 8 (n=1), and station 5 (n=3). No association was found, either between false negative endosonography and T stage, or between overall mediastinal nodal involvement and T stage, location of primary tumor or histology. Surgical procedures. Upon surgical resection, additional mediastinal nodal metastases were found in an additional 6 patients after a negative mediastinoscopy: station 7 (n=1), station 4R (n=1), station 4L (n=1), and station 5 (n=3). The characteristics of the surgical procedures are depicted in Table 2. A mean of 3.4 mediastinal lymph node stations were biopsied during mediastinoscopy. At surgical resection (thoracotomy or VATS), a mean of 4 mediastinal lymph node stations were dissected. For 6 patients, there was no surgical verification of node negative findings at preoperative staging (Figure 1). Study endpoints. The prevalence of mediastinal nodal metastases was 24% overall. According to an intention-to-treat analysis (n=100; Table 4) for detecting mediastinal nodal metastases, sensitivity for endosonography alone was 0.38 (95% CI 0.18-0.57) and sensitivity for endosonography plus cervical mediastinoscopy was 0.73 (95% CI 0.55-0.91). The NPV for endosonography alone was 0.81 (95% CI 0.71-0.91) and for endosonography plus cervical mediastinoscopy 0.91 (95% CI 0.83-0.98). The posttest probability for endosonography alone was 0.19 (95% CI 0.13-0.27), and for endosonography plus cervical mediastinoscopy 0.09 (95% CI 0.04-0.17). As such, a patient with a negative endosonography has a probability of 19% of a positive surgical result with respect to mediastinal lymph nodes. According to a complete cases analysis (n=94) for detecting mediastinal nodal metastases, the sensitivity for endosonography alone was 0.42 (95% CI 0.25-0.61) and 7 the sensitivity for endosonography plus cervical mediastinoscopy was 0.74 (95% CI 0.54-0.88). The NPV for endosonography alone was 0.83 (95% CI 0.74-0.90) and for endosonography plus cervical mediastinoscopy 0.91 (95% CI 0.82-0.96). The posttest probability for endosonography alone was 0.17 (95% CI 0.11-0.25), and for endosonography plus cervical mediastinoscopy 0.08 (95% CI 0.03-0.17). There was no statistical significant difference between the three participating centers based on the multiple imputation data, neither for sensitivity (p=0.35) or NPV (p=0.37) of endosonography alone, nor for sensitivity (p=0.41) or NPV (p=0.61) of endosonography plus mediastinoscopy. Two patients had occult mediastinal nodal disease restricted to station 5 (Table 3). According to a complete cases analysis (n=92) for detecting mediastinal nodal disease within superior and inferior mediastinal nodal stations, the sensitivity and NPV for endosonography alone were 0.45 (95% CI 0.250.67) and 0.85 (95%CI 0.75-0.92), respectively. The estimated NNT based on multiple imputation data was a cervical mediastinoscopy in 10 patients with cN1 NSCLC to identify one case of mediastinal nodal disease after a negative endosonography. Discussion. The most important findings of this study are that one in four patients with cN1 lung cancer on imaging ends up with N2-disease, and that invasive staging with endosonography alone has a sensitivity of 38% to detect N2-disease which can be increased to 73% by adding a mediastinoscopy. The recommendation to use endosonography as the preoperative mediastinal staging tool of choice for all lung cancer patients with a suspicion for mediastinal nodal involvement is based on data from several (non-)randomized clinical trials. These trials included unselected clinical stage I-III lung cancer patients, mainly with suspect mediastinal nodes after imaging (clinical N2). Only a minority of the patients had a centrally located tumor or cN1 with a normal mediastinum on imaging.11,12,15 The current prospective multicenter study is therefore unique in its kind, since we implemented the recommendation by exposing a large cohort of consecutive welldefined patients with cN1 lung cancer to endosonography and tested the assumption 8 made on the role of a confirmatory mediastinoscopy in case no nodal metastasis were found after endosonography. First, we confirm prospectively what was suggested by others concerning the prevalence of N2-disease in cN1 lung cancer despite a normal mediastinum on both CT and PET scan. Twenty-four percent of patients ending up with N2-disease underscores there is no doubt on the indication for preoperative invasive mediastinal nodal staging of cN1 lung cancer. Second, test characteristics of endosonography are disappointingly low for the cN1 lung cancer patient. We found that the sensitivity and NPV of endosonography was 38% and 81%, respectively. A possible explanation is that the majority of the patients (75%) underwent a single EBUS procedure, while only twenty-five patients (25%) had a combined endobronchial and esophageal procedure. The decision to add an esophageal procedure (either with dedicated EUS scope or with the EBUS scope) was left at the discretion of the operator. This decision to add a EUS procedure was based on the need to sample lymph nodes that were inaccessible to the EBUS. This differs from a strategy to perform a systematic nodal mapping of all nodes accessible by both EBUS and EUS. Indeed, the performance of a systematic combined EBUS-EUS procedure could have been of relevance also for the cN1 lung cancer patient. One the one hand, we observed that EBUS did adequately biopsy 9/11 (82%) of the technically reachable false negative stations (Table 3). In 3 patients the mediastinal nodal N2 disease was out of reach for the EBUS technique (stations 5 and 8). On the other hand, we calculated that a maximum of 7 patients could have been picked up with N2-disease provided an EUS procedure was added systematically to the EBUS procedure. With this reasoning, a systematic combined approach might have resulted in a sensitivity of 70% and NPV of 92%, which is in agreement with published results of ASTER 1.10 We see this as an argument that an EBUS procedure alone might be inadequate and that a systematic combined EBUS and EUS procedure could be favorable especially in cN1 patients. Another point is that we did a lobe-specific mediastinal nodal staging during endosonography in the current trial. It has been observed that N2-disease follows a predictable lobe-specific pattern in patients with clinically negative mediastinal nodes by PET-CT scan and that N3 skip metastases are unlikely.16 Overall 23 of 24 patients (96%) had mediastinal nodal N2 disease, while only one patient had non-skip N3 9 disease proven by endosonography. Our strategy translated in a median of 2 mediastinal nodal stations biopsied by endosonography in the current trial, which is less than the 3 mediastinal nodal stations sampled per patient in the ASTER 1 trial. Finally, our data shed a clear light on the role of a confirmatory mediastinoscopy after a negative endosonography. The posttest probability of 0.19 indicates that one should not proceed directly to surgical resection after a negative endosonography. Since endosonography missed (14/24) 58% of N2-disease amongst cN1 patients and since mediastinoscopy picked up at least half of these, we argue that a confirmatory mediastinoscopy should be done. This however implies a considerable cost and investment: we estimated that ten cN1 patients should undergo a mediastinoscopy to detect one patient with N2-disease missed by endosonography. As a consequence, one could question whether endosonography (especially a single EBUS procedure) is really the best choice to start with in resectable cN1 lung cancer patients. Our study has some limitations that deserve attention. First, the endosonography procedure did not require a systematic combined EBUS-EUS assessment of the lobespecific mediastinal nodal stations in all patients. This could have been of importance, since the biopsy of normal sized (<10mm) mediastinal lymph nodes is more challenging by endosonography as compared to enlarged nodes. Second, there were few patients in whom no surgical verification of the nodal status took place. However, with 95% of the patients ending up with a pathological verification of the mediastinal nodal status and only 5% without, we believe the data set is solid. Both intention to treat and complete data set analysis showed comparable results. In conclusion, we analyzed the performance of endosonography in a well-defined cohort of patients presenting with resectable cN1 lung cancer. We found that one in four has N2-disease. We found that endosonography alone has an unsatisfactory sensitivity to detect mediastinal nodal metastasis, and that the addition of a confirmatory mediastinoscopy is of added value. Acknowledgements for each author : Planning of the work : CD, KT, PDL. Conduct of the work : all authors. Reporting of the work : all authors. Responsible for the overall content : CD. 10 References. 1. Watanabe S, Asamura H, Suzuki K, Tsuchiya R. Problems in diagnosis and surgical management of clinical N1 non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(5):1682–1685. 2. Hishida T, Yoshida J, Nishimura M, Nishiwaki Y, Nagai K. Problems in the current diagnostic standards of clinical N1 non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax. 2008;63(6):526–531. 3. Cerfolio R, Bryant A, Ojha B, Eloubeidi M. Improving the inaccuracies of clinical staging of patients with NSCLC: a prospective trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:120713;discussion 1213-4. 4. Kim D, Choi YS, Kim HK, Kim K, Kim J, Shim YM. Heterogeneity of Clinical N1 NonSmall Cell Lung Cancer. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013. doi:10.1055/s-00321333067. 5. Detterbeck FC, Lewis SZ, Diekemper R, Addrizzo-Harris D, Alberts WM. Executive Summary: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 Suppl):7S–37S. 6. De Leyn P, Dooms C, Kuzdzal J, et al. Revised ESTS guidelines for preoperative mediastinal lymph node staging for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014 Feb 26. [Epub ahead of print] 7. Silvestri GA, Gonzalez AV, Jantz MA, et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013 May;143(5 Suppl):e211S-50S. 8. Szlubowski A, Zieliński M, Soja J, et al. A combined approach of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided needle aspiration in the radiologically normal mediastinum in non-small-cell lung cancer staging--a prospective trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010 May;37(5):1175-9. 11 9. Herth FJ, Eberhardt R, Krasnik M, Ernst A. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of lymph nodes in the radiologically and positron emission tomography-normal mediastinum in patients with lung cancer. Chest. 2008 Apr;133(4):887-91. 10. Tournoy KG, Keller SM, Annema JT. Mediastinal staging of lung cancer: novel concepts. Lancet Oncol. 2012 May;13(5):e221-9. 11. Annema JT, van Meerbeeck JP, Rintoul RC, Dooms C, Deschepper E, Dekkers OM, DeLeyn P, Braun J, Carroll NR, Praet M, de Ryck F, Vansteenkiste J, Vermassen F, Versteegh MI, Veseliç M, Nicholson AG, Rabe KF, Tournoy KG. Mediastinoscopy vs endosonography for mediastinal nodal staging of lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010 Nov 24;304(20):2245-52. 12. Yasufuku K, Pierre A, Darling G, et al. A prospective controlled trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration compared with mediastinoscopy for mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011 Dec;142(6):1393-400. 13. De Leyn P, Lardinois D, Van Schil PE, et al. ESTS guidelines for preoperative lymph node staging for non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007 Jul;32(1):1-8. 14. Lardinois D, De Leyn P, Van Schil P, et al. ESTS guidelines for intraoperative lymph node staging in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(5):787– 792. 15. Kang HJ, Hwangbo B, Lee GK, et al. EBUS-centred versus EUS-centred mediastinal staging in lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2014 Mar;69(3):261-8. 16. Shapiro M, Kadakia S, Lim J, et al. Lobe-specific mediastinal nodal dissection is sufficient during lobectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracotomy for early-stage lung cancer. Chest. 2013;144(5):1615–1621. 12 Tables. Table 1. Clinical patient characteristics. Number of patients 100 Age, years, mean (SD) 65 (9.8) Indication, known NSCLC : suspected NSCLC, n 48:52 Primary tumor, localization, n LUL : LLL RUL : RML : RLL 22 : 16 35 : 2 : 25 T stage, n T1a : T1b 18 : 17 T2a : T2b 31 : 20 T3 14 Nodal N1 stage, n by PET (visual FDG avidity) 94 by CT (short axis 10mm) 68 Hilar nodal N1 station, n 10 : 11 : 12 13 : 73 : 14 Hilar nodal station, short axis largest node, mm mean (SD) 12 (5) Final pathological diagnosis NSCLC, n adenocarcinoma 51 squamous cell carcinoma 36 NSCLC NOS 4 large cell carcinoma 3 other : LCNEC; carcinoid; mucoepidermoid Ca 4 Benign, n tuberculosis 1 normal lung parenchyma 1 13 Table 2. Endosonography and surgical procedure findings. Endosonography findings (n=100) Type of endosonography performed EBUS-TBNA only , % 75 EBUS-TBNA + EUS-FNA , % 15 EBUS-TBNA + EUS-B FNA , % 10 Type of sedation, % Moderate sedation : General anesthesia 94:6 Short axis of largest mediastinal lymph node, mm mean (SD) 6.9 (2.2) Number of mediastinal nodal stations observed mean (SD) 3.2 (0.7) Number of mediastinal nodal stations biopsied mean (SD) 2.1 (1.1) Number of mediastinal lymph nodes biopsied mean (SD) 2.3 (1.2) Surgical findings CERVICAL MEDIASTINOSCOPY (n=75) Number of mediastinal nodal stations biopsied mean (SD) 3.4 (1.0) SURGICAL RESECTION (n=77) Number of mediastinal nodal stations dissected mean (SD) 4 (1.7) Type of surgery (bi)lobectomy 67 pneumectomy 7 segmentectomy or wedge resection 3 14 Table 3. Characteristics of patients with false negative endosonography findings. N Local T-stage Final PA Endosonography+ mediastinoscopy Node metastasis EBUS adequately done ? EUS of potential added value ? 1 RML T3 Large cell Ca true positive station 7 at mediastinoscopy Yes No, has been done 2 LLL T1a Large cell Ca false negative stations 5 and 8 at resection Out of reach Yes, was not done 3 RUL T2a Adenocarcinoma true positive stations 2R and 4R at mediastinoscopy No, inadequate sample No, out of reach 4 RLL T2a Adenocarcinoma false negative station 4R at resection Yes No, out of reach 5 RLL T2a Squamous cell Ca true positive station 7 at mediastinoscopy Yes Yes, was not done 6 RLL T2a Adenocarcinoma true positive station 4R at mediastinoscopy Yes No, out of reach 7 LLL T1b Adenocarcinoma true positive station 4L at mediastinoscopy No, inadequate sample Yes, was not done 8 LUL T2b Adenocarcinoma false negative station 5 at resection Out of reach No, out of reach 9 RLL T2b Adenocarcinoma false negative station 7 at resection Yes Yes, was not done 10 LLL T2a adenocarcinoma false negative station 4L at resection Yes Yes, was not done 11 LUL T2a Adenocarcinoma false negative station 5 at resection Out of reach No, out of reach 12 RUL T1b LCNEC true positive station 7 at mediastinoscopy Yes Yes, was not done 13 RLL T3 Carcinoid na station 7 at resection Yes Yes, was not done 14 RUL T2a Adenocarcinoma true positive station 4R at mediastinoscopy Yes No, out of reach 15 Table 4. Diagnostic performance based on multiple imputation analysis. Endosonography alone Endosonography + cervical mediastinoscopy Sensitivity 0.38 (0.18-0.57) 0.73 (0.55-0.91) Negative Predictive Value 0.81 (0.71-0.91) 0.91 (0.83-0.98) Posttest Probability 0.19 (0.13-0.27) 0.09 (0.04-0.17) 16 Figure 1. Flow chart of patients undergoing mediastinal nodal staging for clinical N1 (suspected) non-small cell lung cancer. N, number of patients. * patient refusal or physicians’ choice not to perform a mediastinoscopy after a negative endosonography ** physician decided to give induction chemotherapy, based on N1 proven by EBUS 17