Woodland Art Symbolism

advertisement

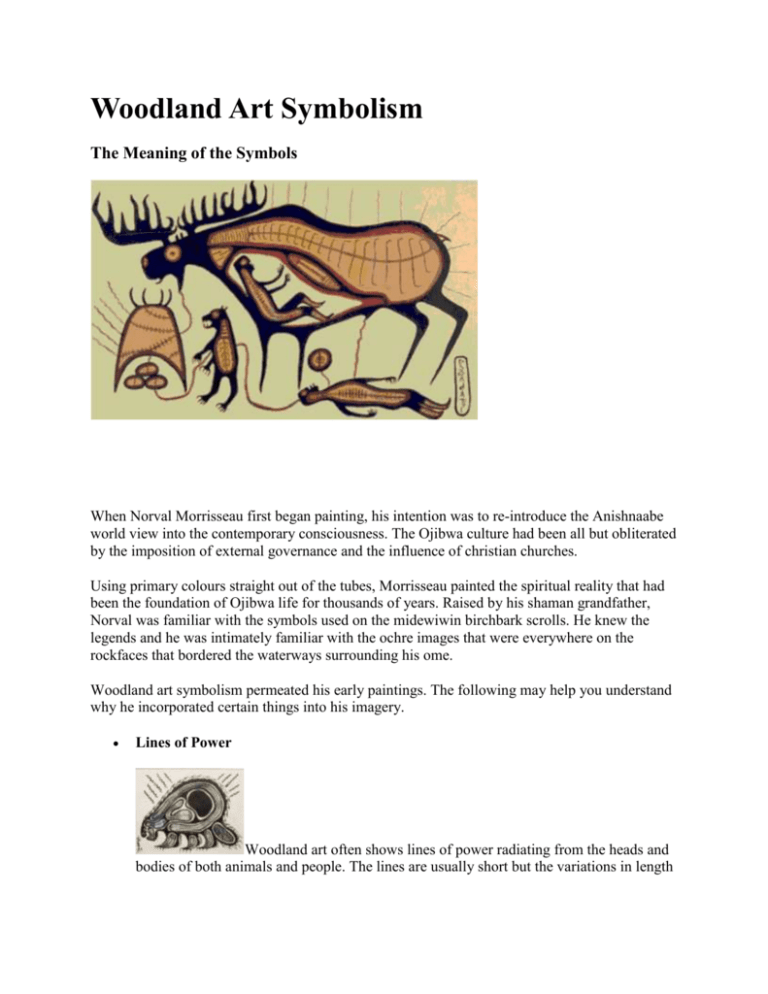

Woodland Art Symbolism The Meaning of the Symbols When Norval Morrisseau first began painting, his intention was to re-introduce the Anishnaabe world view into the contemporary consciousness. The Ojibwa culture had been all but obliterated by the imposition of external governance and the influence of christian churches. Using primary colours straight out of the tubes, Morrisseau painted the spiritual reality that had been the foundation of Ojibwa life for thousands of years. Raised by his shaman grandfather, Norval was familiar with the symbols used on the midewiwin birchbark scrolls. He knew the legends and he was intimately familiar with the ochre images that were everywhere on the rockfaces that bordered the waterways surrounding his ome. Woodland art symbolism permeated his early paintings. The following may help you understand why he incorporated certain things into his imagery. Lines of Power Woodland art often shows lines of power radiating from the heads and bodies of both animals and people. The lines are usually short but the variations in length and intensity indicate the quality of power. The lines can both transmit and recieve information. Lines of Communication Woodland artists often portray animals and people joined with flowing lines which indicate relationships which reflect the artist's understanding of the nature of the interdependence between the two beings. This is a recent painting by Goyce Kakegamic depecting the legend of Red Lake. Lines of Prophecy Some powerful creatures may have narrow ivy-like lines spewing from their mouths which indicate more than simple speech - they indicate prophecy, particularly in association with shaman imagery. A good example is this painting by Norval Morrisseau showing a shaman making direct communication with the universal life force. Lines of Movement Very short lines, clustered near an organ like a heart as in this example, indicate movement and an active attempt at communication with the viewer. The lines are particularly significant surrounding shaking tent imagery. The Divided Circle A circle divided in half, connected with the main image by lines of communication is an especially meaningful symbol used by woodland artists. The divided circle represents dualities present in the world - good and evil, day and night, sky and earth, honest and dishonest, function and dysfunction for example. X-Ray Decoration The term would have been meaningless to prehistoric woodland artists, but nowadays the concept of an x-ray view aptly describes the way woodland artists depict inner structures of people and animals. They are representations of inner spiritual life. Colour In prehistoric times the only significant colour used was red ochre as in this ancient image of mishpashu (a water spirit) on a cliff overlooking Lake Superior Fortunately Norval Morrisseau had a broader palette. He painted with unmixed acrylics straight from the tube for most of his career. He used colour intuitively to reflect what he said was the inner reality of the inner being. Woodland art symbolism was most prominent in the early legend painters like Eddy Cobiness, Carl Ray and, of course, Morrisseau himself. Symbolism was evident in the early works of Blake Debassige and Martin Pannamick. Woodland art symbolism is still a prominent in many of Leland Bell's work...particularly divided circles but sometimes he incorporates discrete lines of power. Leland Bell is Anishinabe from the Wikwemikong Unceded First Nation on Manitoulin Island. He is Loon Clan and a second degree member of the Three Fires Midewiwin Society. Leland was one of the young men mentored by members of the Indian Group of Seven at the Manitou Arts Foundation, a summer school that operated on Schreiber Island in 1972. He was deeply inspired by the work of the Woodland artists and with the help of elders has made the connection between the Anishnabe concept of vision quest and his own committment to living life as a good being. Leland Bell's paintings are of stylized human figures sharing the affinity of family or friends, often depicting imagery of nurturing, sharing, learning, peace and serenity. "My art comes from the Three Fires (or Midewiwin) tradition. That is what I believe in. I came to this belief through a dream I had about peace. It was a deeply spiritual experience. After consulting with Elders I began trying to build my sense of spirituality. Then I needed to have an Indian name. I consulted with some elders and asked them to help me find my name. I was given the name Bebaminojmat which, loosely translated, means, 'when you go around you talk about good things'. Then I fasted to prepare my body and my mind to talk to the Creator. This is where my art comes from. "The circle is central to our tradition. The Creator sits in the East. Yellow is the colour for that direction; the sacred herb is tobacco; the animal is the eagle. Red is the colour of the South which is the place of all young life, of the little animals; the sacred plant is cedar. The West is the place of life; it's colour is black and the sacred medicine is sage. All the healing powers come from the North; its colour is white; sweetgrass comes from there; and that is where the sacred bear sits. "The Circle is what my paintings are based on. The rounded lines are deliberate ... what I create is something simple and serene and peaceful." All the paradigms that sustain his creativity exist within his Anishinabe culture. He says that he absorbs what he needs and discards what he doesn't need from other cultures and is committed to remain Anishinaabe.