Running head: THE DEFENSE OF MARRIAGE ACT

advertisement

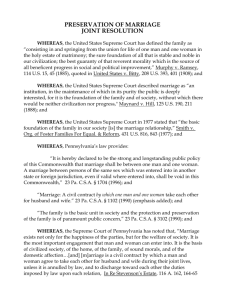

The Defense of Running head: THE DEFENSE OF MARRIAGE ACT The Defense of Marriage Act Should Be Overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court: Analysis of Equal Protection and Full Faith and Credit Clauses of the U.S. Constitution Cornell College 1 The Defense of 2 Abstract This paper seeks to analyze the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) under the purview of constitutional law. It demonstrates how DOMA should be overruled on grounds of constitutionality. This is seen through both Equal Protection and Full Faith and Credit analysis. I explore how precedent evokes a substantive argument for overruling DOMA, as well as issues that would arise from doing so and how they should be addressed. Additionally, strict scrutiny review is exercised to demonstrate the unconstitutionality of DOMA. The impact of court cases such as Varnum v. Brien are examined and issues of inconsistency are analyzed. Public health analysis also leads to the conclusion that same-sex marriage should be legalized. The Defense of 3 The Defense of Marriage Act Should Be Overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court: Analysis of Equal Protection and Full Faith and Credit Clauses of the U.S. Constitution I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people's religious beliefs over others. Especially if it denies people's civil rights. I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard's and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That's what Loving, and loving, are all about. –Mildred Loving, June 12, 2007. In light of that statement regarding same-sex marriage, we see that this contentious debate is not a new one. The U.S. Supreme Court first addressed the institution of marriage in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), in which they posited: We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights - older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred. It is an association that promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects. Yet it is an association for as noble a purpose as any involved in our prior decisions. Indeed, marriage as an institution reaches far back into time, beyond the duration of our own government and U.S. Constitution. As one of the most frequently contested issues in the United States today, marriage carries with it a plethora of issues and conflicts. Clearly Griswold was not about same-sex marriage, and neither was a subsequent case, Loving v. Virginia (1967). In Loving (1967), the U.S. Supreme Court articulated: Marriage is one of the "basic civil rights of man," fundamental to our very existence and survival....To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State. The Defense of 4 The combination of these two cases established the right to marry as a fundamental right. They established this using equal protection analysis. This is stated in the Constitution, guaranteed in the Fourteenth Amendment, “No State shall…nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the law” (U.S. Const., amend. XIV, § 1). It is in the spirit of that dictumthat we come to the issue at hand: The issue of same-sex marriage. There has been no U.S. Supreme Court decision regarding same-sex marriage, nor has there been any constitutional amendment either prohibiting or allowing such an institution. However, in 1996, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). This Act was passed in light of a pending decision by the Hawaii Supreme Court. In effect the Act nullifies federal recognition of State issued marriage licenses between same-sex partners and also instructs States that they are not required to recognize such marriage as would be provided under the Full Faith and Credit Clause of the U.S. Constitution. It is my conclusion that the U.S. Supreme Court should declare the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional based on analysis with respect to the Full Faith and Credit and Equal Protection Clauses of the U.S. Constitution. The following paragraphs will discuss a myriad of reasons why DOMA should be overruled based on a variety of grounds including but not limited to full faith and credit, equal protection, public interest, and judicial consensus. DOMA is a relatively new piece of legislation, having been passed only about a decade ago. DOMA came about as a result of the case of Baehr v. Miike (1996). On December 17, 1990, Ninia Baehr et al. filed suit after having civil marriage licenses denied to them on the basis that they were all same-sex couples. Judgment in favor of the defendant was entered on October 1, 1991, and the plaintiffs appealed to the Supreme Court The Defense of 5 of Hawaii. The Supreme Court of Hawaii reversed the lower court’s decision in 1993 and declared that under strict scrutiny analysis a statute prohibiting marriage on same-sex grounds was unconstitutional. The case was remanded to the lower court which was ordered not to bar issuance of marriage licenses on basis of sex. The Hawaii legislature, in response, passed an amendment to the Hawaii Constitution on April 29, 1997, which reserved marriage to opposite sex couples. Upon appeal of the case once more to the Supreme Court of Hawaii by the defendant, the Court reversed its decision on the basis of the new amendment therefore invalidating the plaintiffs’ complaint (Baehr v. Miike, 1996). The 1996 Defense of Marriage Act Public Law 104-199, otherwise known as the Defense of Marriage Act, was enacted by the 104th Congress on Sept. 21, 1996. This Act is actually quite brief and revises Title 28 of the United States Code so that: No State, territory or possession of the United States, or Indian tribe, shall be required to give effect to any public act, record, or judicial proceeding of any other State, territory, possession, or tribe respecting a relationship between persons of the same-sex that is treated as a marriage under the laws of any other State, territory, possession, or tribe, or a right to claim arising from such relationship. This in effect supersedes and/or preempts the Full Faith and Credit Clause of the U.S. Constitution, effectively allowing a State to refuse to recognize a marriage license from another state if it should so choose. The guiding principle behind such a change is because otherwise once a state like Massachusetts recognizes same-sex marriage, essentially all of the other 49 states are required to do so by the Full Faith and Credit Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which holds that, “Full Faith and Credit shall be given in each State to the public Acts, Records, and judicial Proceedings of every other State. And the Congress may by general Laws prescribe the Manner in which such Acts, Records and Proceedings shall be proved, and the Effect thereof” The Defense of 6 (U.S. Const., art. IV, § 1). In order to nullify such constitutionally mandated recognition of marriage, the Act was passed. In addition to the above provision, the Act also redefines on the national level what a marriage is. The Act amends Title 1 of the U.S. Code so that: In determining the meaning of any Act of Congress, or of any ruling, regulation, or interpretation of the various administrative bureaus and agencies of the United States, the word ‘marriage’ means only a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife, and the word ‘spouse’ refers to only a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or wife” (Defense of Marriage Act, 1996). This effectively achieves two objectives. First, it limits marriage at the federal level to that between a man and a woman, and secondly it ensures that states are not compelled to recognize any same-sex marriage under the above definition due to transference under Full Faith and Credit. Without getting into deep legal arguments about the legality or underlying issues with DOMA, a surface level analysis reveals several key issues which are immediately important for purposes of analysis. First, that such an Act of Congress inherently places same-sex marriage in the national and/or federal view. Secondly, that such an Act clearly seeks to prevent an obvious outcome: same-sex marriage. Third, that such an Act incontrovertibly seeks to apply the rule of law to a discrete group of persons: homosexuals. Fourth, that the Act, while not making samesex marriage illegal outright, certainly seeks to place an obstacle in the way of those seeking such a union. Finally, as Theresa Goulde, J.D. Candidate at Tulane University Law School observes, “Congress enacted DOMA both to preserve the heterosexual definition of marriage and to advance the government’s interest in defending traditional, Judeo-Christian moral norms” (Goulde, 2005, p. 197). Judicial precedent effects a substantive argument in favor of same-sex marriage. The Defense of 7 Jurisprudentially speaking, there is a clear argument to be made in favor of same-sex marriage. Examination of the case law provides a clear and concise legal framework for an argument in favor of same-sex marriage. The most obvious precedent is Loving v. Virginia (1967). This is the key case in which equal protection of the law is extended to prevent discriminatory exclusion of marriage based on race. The case involves a white male who married a black female in Washington, D.C., but then elected to return to Virginia to reside. They were then convicted under Virginia statute for violating the anti-miscegenation laws within the Virginia Code. The Court ruled that the law was unconstitutional under purview of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Even though the statute applied equally to whites and blacks, the U.S. Supreme Court still struck it down on the ground that it was forbidden to deny the right to marry, which the Court articulated was a fundamental right, based solely on classifications. The decision preceding Loving is that of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). In Griswold (1965), a statute held that it was a crime to use “any drug, medicinal article or instrument for purpose of preventing conception,” and Estelle Griswold and Lee Buxton, who dispensed information, instruction and medical advice to married couples about birth control, were charged for violating that statute as an accessory to that offense. The Supreme Court articulated that “specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.” It is these “penumbras” which are then explained as “zones of privacy” later invoked in Roe v. Wade (1973). In Griswold (1965), the Court further concluded, “Such a law cannot stand in light of the familiar principle, so often applied by the Court, that a ‘governmental purpose to control or prevent activities constitutionally subject to state regulation may not be achieved by means which sweep The Defense of 8 unnecessarily broadly and thereby invade the area of protected freedoms’ NAACP v. Alabama 377 U.S. 288, 307.” Taken together, these two cases establish as fundamental judicial principle that marriage is in fact a fundamental right, which cannot be abridged by state statute regarding race nor invaded by governmental interests involving contraception. This establishes marriage as a fundamental right and a protected institution under constitutional law. There are two more cases which require attention. The first of these is merely to act as a reference point for the second. These cases are Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) and Lawrence v. Texas (2003), respectively. In Bowers (1986), two men were charged with violating a Georgia statute prohibiting consensual sodomy, which they had obviously engaged in. The Court, rejecting the plaintiffs’ argument that their constitutional rights to privacy and association were violated by the statue, upheld the law. The Court held that, in blatant disregard to the constitutional issues at hand, there was no constitutional right to consensual homosexual sodomy. This ruling was then completely overturned nearly two decades later in Lawrence (2003). While also about sodomy statutes, Lawrence (2003) overruled Bowers (1986) because “its continuance as precedent demeaned the lives of homosexual persons” (Lawrence v. Texas, 2003). The Court, citing Casey, asserted that “Our obligation is to define the liberty of all, not to mandate our own moral code,” and “It is a promise of the Constitution that there is a realm of personal liberty which the government may not enter” (Lawrence v. Texas, 2003). It also held that “When homosexual conduct is made criminal by the law of the State, that declaration in and of itself is an invitation to subject homosexual persons to discrimination both in the public and the private spheres” (Lawrence v. Texas, 2003). The final holding and directive of the Supreme Court in Lawrence was very clear: “The petitioners are entitled to respect for their private lives. The Defense of 9 The State cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime. Their right to liberty under the Due Process Clause gives them the full right to engage in their conduct without intervention of the government.” (Lawrence v. Texas, 2003). The Court succinctly upholds both privacy and a right to due process simultaneously as they apply it in Lawrence. The final case of relevance is that of Romer v. Evans (1996). In this case the Court struck down Amendment 2 to the Colorado Constitution, an amendment which sought to annul antidiscrimination regulations adopted by the cities of Aspen, Boulder and Denver prohibiting private and public discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. In the Opinion of the Court, Justice Kennedy affirms that “A law declaring that in general it shall be more difficult for one group of citizens than for all others to seek aid from the government it itself a denial of equal of protection of the laws in the most literal sense” (Romer v. Evans, 1996). Furthermore, the Court argued that Amendment 2 failed the rational basis standard of review: “We conclude that, in addition to the far reaching deficiencies of Amendment 2 that we have noted, the principles it offends, in another sense, are conventional and venerable; a law must bear a rational relationship to a legitimate governmental purpose, and Amendment 2 does not” (Romer v. Evans, 1996). The Opinion culminates in the blatantly direct denouncement of Amendment 2 as essentially absurd and unacceptable. The Court held that “It [Amendment 2] is a status-based enactment divorced from any factual context from which we could discern a relationship to legitimate state interests; it is a classification of persons undertaken for its own sake, something the Equal Protection Clause does not permit” (Romer v. Evans, 1996). In this case, the Court has extended further the umbrella of equal protection that had been held over race and sex to the category of sexual orientation. This case necessarily includes gays and lesbians as a suspect class, deserving of The Defense of 10 equal protection under the law. This massive amount of case law will all become highly relevant momentarily. Based on the case law we can see that there are several fundamental premises established by the Court. First, that marriage is a fundamental right. Second, the right to marriage cannot be infringed upon by a variety of statutes and provisions, regardless of governmental interest in things like child welfare. Indeed, even incarceration does not preclude the right to marry as seen in the case of Turner v. Safley (1987). Third, the “zones of privacy” articulated in Griswold (1965) extend not only to protect married couples, but also extend over homosexual conduct in the privacy of one’s own home. The Court necessarily, in Lawrence (2003), holds that the law cannot be used as a weapon of the majority against homosexuals and their conduct. Or as Justice O’Connor so blithely puts it, that moral disapproval is not a legitimate state interest to justify a criminal statute against a class of citizens under rational basis review (See O’Connor, J., concurring, Lawrence v. Texas, 2003). Finally, that equal protection applies to sexually oriented minorities as much as it does to historical minorities and disadvantaged groups such as women. This all becomes highly relevant when taken together as a whole. If marriage is so fundamental, and homosexual conduct is neither punishable nor discriminable under law, then what barrier is there to same-sex marriage? My answer is none. It logically and jurisprudentially follows from the case law above that if marriage is a fundamental right, and if we cannot discriminate against homosexuals or their conduct, they should be allowed to marry each other. The Court has already extended the penumbra of privacy, as it were, to protect homosexuals under equal protection, as can be clearly seen from the case law. Analysis of the judicial precedent and case law invites one to look at the big picture and see how it is rather apparent that same-sex marriage is not as farfetched as some people would believe. It The Defense of 11 seems as though moral opinion of the majority is the only reason which inhibits a jurisprudence that would allow same-sex marriage. As above, this is clearly insufficient within the law. Objecting to same-sex marriage on purely “moral” or religious grounds raises questions that the judiciary should not address. As articulated above, a moral argument for exclusion of homosexuals from the social and legal, not religious institution of marriage, is insufficient at best. Clearly, religious institutions may regulate or prohibit marriage within their purview as they please. However, there are still individuals and groups that protest such allowance for same-sex marriage because it offends religion. Case in point here is that since there is a separation between church and state, such an argument is not only insufficient, but should be disregarded in its entirety by the judiciary. This is due to the fact that adjudication on purely religious or majority grounds is not only unacceptable but undesirable. Morality, while it may play a significant part in law, especially criminal law, is not sufficient for justification of exclusion of homosexuals from the institution of marriage. The Superior Court of Washington provides jurisprudential guidance on this very subject in the case of Andersen v. King County (2006). In the case, Judge William Downing concluded that the DOMA statute of Washington State could not “survive analysis under the rational basis standard, and held them violative of the privileges and immunities and due process clauses of the Washington Constitution” (Anderson v. King County, 2006). Judge Downing also argued that “In our pluralistic society, in which church and state are kept scrupulously separate, the moral views of the majority can never provide the sole basis for legislation” (Andersen v. King County, 2006). He also concluded that “serving tradition, for the sake of tradition alone, is not a compelling state interest” (Andersen v. King County, 2006). Judge Downing additionally refers us to Justice O’Connor’s Opinion in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), “Indeed, we have never held that moral The Defense of 12 disapproval, without any other asserted state interest, is a sufficient rationale under the Equal Protection Clause to justify a law that discriminates among groups of persons.” Based upon the above jurisprudence, it can be seen how it is not only legally insufficient for the judiciary to make decisions about same-sex marriage on religious grounds, but that it is indeed forbidden to do so by the Constitution itself, through application of the First Amendment. DOMA intrinsically violates the Full Faith and Credit Clause, as well as superseding it outright, in turn violating the Supremacy Clause. DOMA is a federal law, and its purpose was and is to prevent States from having to recognize same-sex marriages issued by other States against their will due to the legitimizing effect of the Full Faith and Credit Clause, supra. There is, however, a key constitutional issue with this statute. As a means of overcoming Full Faith and Credit, Congress passed this law, but it would appear that doing so was unconstitutional. There are two main issues to be raised with respect to this issue. The first is that of an extension of legislative power forbidden by the Constitution. The Full Faith and Credit Clause would appear on its face to be an allowance to the Congress to extend the power, “…And the Congress may by general Laws…” (Const. art. IV, § 1), but providing such a “negative” power as that granted by DOMA is unseemly. As Jennie Shuki-Kunze, of the Case Western Reserve Law Review writes: The Clause states that Congress may legislate as to the “effects” of acts, records, and judicial proceedings of one state in another. However, the Clause confers no power authorizing Congress to decree one state’s acts, records or proceedings have no effect in the state of another. While an affirmative legislative power may be supported by the language of the Clause, it is unlikely that the Framers intended to provide Congress with a “negative” power under the Clause as well. While the Clause states Congress may legislate as to the “effect” of one state’s acts or judgments in another, it does not declare that Congress may give these acts or judgments no effect whatsoever (Shuki-Kunze, 1998, p.361). This is truly the issue at hand. A granting of power to nullify the acts of other states would appear to be in contradiction to the very intent of the Full Faith and Credit Clause. How is the The Defense of 13 power to annul the acts of States consistent with the ideal of recognizing that which is carried out in other States? I assert that it is not. The purpose of the Full Faith and Credit Clause was “in order to facilitate state unity and uniformity” (Shuki-Kunze, 1998, p. 361). This is a logically prudent argument. Without such a guarantee, the entire Constitution bears significantly less muster, and we would be reduced to a glorified version of the Articles of Confederation. This is clearly not the purpose or intent of the Framers, nor of the Constitution itself. Ergo, the very nature of the Full Faith and Credit Clause in its creation is an additive function: It was designed to allow Congress to expand and expound the powers so described-Not to nullify them entirely, which is clearly subtractive in nature. The second issue that arises is more diaphanous and evanescent. The issue is that of federalism, and the inherent separation of power. It is fairly obvious that marriage and its regulation is reserved to the States. That fact is not in question. They have made the law, according to the very text of the Full Faith and Credit Clause itself, to “prescribe the Manner in which such Acts, Records and Proceedings shall be proved, and the Effect thereof” (Const. art. IV, § 1). This is also not in doubt. What Congress has done, however, is given its power, the power to “proscribe…the Effect thereof” (Const. art. IV, § 1) unto the States themselves. Not only this, but they have given the negative power, the power of nullification, unto the States. This is a grievous issue. This is not limited to purely legislative actions, however. It also applies to the judiciary. As set forth over a century ago in Roche v. McDonald (1928): The Full Faith and Credit Clause requires that the judgment of a state court which had jurisdiction of the parties and the subject matter, shall be given in the courts of every other state the same credit, validity, and effect as it has in the state where it was rendered, and be equally conclusive upon the merits, and that only such defenses as would be good to a suit thereon in that state can be relied on in the courts of any other state. The Defense of 14 A further argument, although perhaps less substantive and more peripheral, is one of judicial power in its normative form. The traditional theory of separation of powers holds that the legislative branch makes the laws, the executive branch enforces the laws, and the judiciary interprets the laws. Inherent in this is the power of the judiciary, most notably the U.S. Supreme Court, to declare an act of Congress unconstitutional. That is to say, the Supreme Court can nullify an act of Congress if it is in violation to the Constitution. It would appear that Congress has attempted to utilize this power of nullification as its own. If that is not enough, it has further dug itself into a Constitutional sinkhole by granting that power to the States. It has, in effect, delegated its power to the States, which was clearly not the intent of the Framers. Otherwise they would not have included the Tenth Amendment “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people” (U.S Const., amend X). This clearly marks a separation between the powers of the States and the federal government. The Framers of the Constitution would have an aneurysm if they found out that Congress had delegated such power to the States, and the nature of such power. That is how it would seem at least. It at least raises some interesting questions surrounding the very nature of DOMA itself, and its facial viability under the Constitution. In essence, the Full Faith and Credit issues raised above are themselves compounded by another. This final issue is that of DOMA superseding and/or preempting the Full Faith and Credit Clause. This is impermissible due to the power of the Supremacy Clause, which holds that “This Constitution and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States shall be the supreme Law of the Land” (U.S. Const., art. VI). In essence, all law must give way to the Constitution if it is conflict to it; i.e. the Constitution is sovereign. It would seem that DOMA The Defense of 15 does this very thing. By seeking to preempt or supersede the Constitution, DOMA intrinsically violates the Supremacy Clause. Based on this analysis, DOMA should be ruled unconstitutional as a prima facie case, even disregarding its content. DOMA has substantive issues under Full Faith and Credit examination and so it remains in contradiction to the constitutional law. Discrimination against homosexuals by forbidding same-sex marriage inherently creates a suspect class that is protected under Equal Protection, as established by judicial precedent. In the vast body of case law, one of the most frequently cited footnotes is number 4 of United States v. Carolene Products Company (1938), which I will invoke now. In footnote four, the Supreme Court held that prejudice against discrete and insular minorities is deserving of strict judicial scrutiny. Strict scrutiny was first applied in Korematsu v. U.S (1944). This discrete/insular/minority pretest to determine level of scrutiny was later applied to associate strict scrutiny with racial discrimination and intermediate scrutiny with sex based discrimination. Homosexuals are clearly a discrete, insular minority. More so, in fact, than even women, who have been traditionally disadvantaged by our patriarchal society. However, while women are certainly discrete, they are not a minority statistically speaking, and may or may not be insular according to the Carolene (1938) definition of that term. Based on this, it would seem apparent that strict scrutiny is necessarily the judicial standard of review when it comes to sexuallyoriented legislation concerning homosexuals. Moreover, strict scrutiny requires that there be a “compelling governmental interest,” that the statue be “narrowly tailored” and that it must use “the least restrictive means” to achieve that interest, as asserted in Korematsu v. U.S (1944). There is a way to determine if a group is a “suspect class.” A group is a suspect class if they are: (1) a "discrete" or "insular" minority who (2) possess an immutable trait, (3) share a history of discrimination, and (4) are powerless to protect themselves via the political process (United States v. Carolene Products Company, 1938). The Defense of 16 We have already established (1) above, homosexuals possess an immutable trait, namely their sexual orientation (this is supported by vast amounts of biopsychological research), they certainly share an obvious history of discrimination, and due to their status as a discrete insular minority are powerless to protect themselves via the political process. Based on these substantive criteria, also articulated in footnote four of Carolene, we can clearly conclude that homosexuals are a suspect class based on judicial precedent. We can also conclude that strict scrutiny is the standard of judicial review in cases involving homosexuals. Ergo, in a case about same-sex marriage, the Equal Protection Clause necessarily invokes strict scrutiny, demanding a compelling governmental interest. Clearly however, this is not the case. The Defense of Marriage Act explicitly forbids same-sex marriage recognition. In a court of law, application of strict scrutiny requires a compelling governmental interest to pass the test. I can see none. What compelling interest is there, other than tradition, which is not compelling at all? I say none. There is no compelling interest. If the Supreme Court is going to fairly apply the Equal Protection Clause, which guarantees us that “No State shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws” (U.S. Const., amend. XIV, § 1), then DOMA would seem to fail equal protection analysis using strict scrutiny. Thus, DOMA should be overturned by the Supreme Court, in interest of protecting liberty and constitutional rights to equal protection under the law. Rulings such as Varnum v. Brien create a general inconsistency in judicial case law as well as public policy which results in discrepancies which the Supreme Court historically has dealt with, and should do so again. If we follow the above recommendation to overrule DOMA, we come up with another issue: Full Faith and Credit would then apply once more so that once one state accepts same-sex marriage, effectively all states must do so. This is an issue in and of itself. On April 3, 2009, the The Defense of 17 Iowa Supreme Court handed down its (unanimous) decision in the case of Varnum v. Brien (2009). In this case, the court held that refusing marriage to same-sex couples inherently denied them equal protection under the law assured by the Iowa Constitution. Citing esteemed Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, the court asserts that, “It is revolting to have no better reason for a rule of law than that so it was laid down in the time of Henry IV. It is still more revolting if the grounds upon which it was laid down have vanished long since, and the rule simply persists from blind imitation of the past” (Varnum v. Brien, 2009). Utilizing an intermediate scrutiny standard, which requires that “a statutory classification must be substantially related to an important governmental objective” citing Clark v. Jeter, (1988), the Court held that the Iowa statute defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman fails the intermediate scrutiny test. Addressing a variety of issues, from religious objections to “family value” arguments, the Court asserts that it would seem to be that it is actually in the best interest of the State to allow same-sex marriage, jurisprudence notwithstanding. Their reasoning is that same-sex couples are allowed to raise children, so it would be better for their caretakers to be solidly committed and bound to each other through marriage, forming a “family” which opposition to same-sex marriage argues is actually diminished by same-sex marriage. As the Iowa Supreme Court so clearly puts it: We have a constitutional duty to ensure equal protection of the law. Faithfulness to that duty requires us to hold Iowa’s marriage statute, Iowa Code section 595.2, violates the Iowa Constitution. To decide otherwise would be an abdication of our constitutional duty. If gay and lesbian people must submit to different treatment without an exceedingly persuasive justification, they are deprived of the benefits of the principle of equal protection upon which the rule of law is founded (Varnum v. Brien, 2009). However, the Iowa Supreme Court is not the only court to hold this. This is seen in the case of Goodridge v. Department of Public Health (2003) in which the Supreme Judicial Court of The Defense of 18 Massachusetts asserted that “the [same-sex] marriage ban worked a deep and scarring hardship on a very real segment of the community for no rational reason” (Eaton, 2007). Sarah Eaton (2007) affirms: After Goodridge, the Massachusetts Senate requested an opinion from the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts concerning a proposed bill that would limit marriage to opposite-sex couples, but would create a parallel civil union structure for same-sex couples. The court concluded that the bill would only “maintain an unconstitutional, inferior, and discriminatory status for same-sex couples” in violation of the equal protection and due process guarantees of the Massachusetts Constitution. These two courts both hold that suppressing same-sex marriage violated equal protection of the law. It would seem that they both independently came to this conclusion. This raises an adjudicative dilemma, especially when legislators are passing laws and other courts are handing down rulings accepting prohibition of same-sex marriage as unconstitutional. First let us look to another issue before addressing this one. It is the public policy and public health issue of same-sex marriage. The public health term I use here is broad in a general sense: I do not mean physiological health. In reference to public health, I am referring to that asserted by John Culhane, Professor of Law and Director, Health Law Institute, Widener University School of Law, who discusses the “health (and safety) of the population as a whole” (Culhane, 2008, p.12). Citing Goodridge, Culhane states “Marriage is a vital social institution. The exclusive commitment of two individuals to each other…brings stability to our society” (Culhane, 2008, p. 17). Culhane furthers his analysis by giving statistics showing that married people: live longer, are less likely to suffer from chronic illness or longterm disability, are less likely to suffer from mental health issues, and make more money. He also provides a counterargument by providing that “They [studies] also suggest that the major health benefits found in married couples do not arise between cohabitating partners” (Culhane, The Defense of 19 2008, p. 28). Justice Thurgood Marshall also comments on the family, although he was not speaking about same-sex marriage when he said, in the case of Zablocki v. Redhail (1978): It is not surprising that the decision to marry has been placed on the same level of importance as decisions relating to procreation, childbirth, child rearing, and familial relationships. As the facts of these cases illustrate, it would make little sense to recognize a right to privacy with respect to other matters of family life and not with respect to the decision to enter into a relationship that is the foundation of the family in our society. However, these two issues create a larger one: Inconsistency. The Supreme Court has traditionally denied certiorari to cases which it deemed did not possess “ripeness,” that is they had sufficiently passed through the lower courts and that it is an issue which the Court feels it is both able and willing to address. The same-sex marriage issue has been percolating for some time now, and with cases like Varnum v. Brien (2009) being handed down, the time is now. Allowing for some courts to issue one ruling while other courts issue another does not serve the interests of jurisprudence, even though these cases deal with State Constitutions, rather than the federal Constitution. There is still a variety in both the rulings and reasoning of these lower courts. This variation serves neither the judicial nor public interests in the matter of same –sex marriage. Discrepancies in case law arising from such decisions have traditionally been dealt with, and the court should do so again. This will necessarily solve the issue intrinsic to overruling DOMA and serve both judicial and public health interests. Conclusion We have examined a variety of issues surrounding same-sex marriage and DOMA. These issues include everything from judicial precedent as a matter of jurisprudence to intrinsic issues of constitutionality. This analysis sought to examine DOMA and provide reasons, judicial and otherwise, why it should be overruled. These reasons, both individually and cohesively support my argument for overruling DOMA, and consequently providing a ruling on same-sex marriage The Defense of 20 as a point of law. I think the vast amount of issues I have raised casts DOMA in a light of doubt that we should jurisprudentially acknowledge, and overrule. It is for these reasons, expounded above, why I hold that DOMA is unconstitutional, and should be overruled. In the end, however, we must look at the broader issues here as well. This analysis is certainly about same-sex marriage. But on a broader context it is about more than that. This case is about giving justice to a group of citizens who has experienced historical repression at the hands of the government as well as society. It is also about the rights of gays and lesbians to have equal protection and due process under the law, the same as all people if our Constitution is to be believed. In the end, the Supreme Court can assure that “We the People” and “All men (and women, of all races, religions and sexual orientations) are created equal” are upheld in our society. In the end, this analysis raises some questions while it in turn seeks to answers others. Is a Constitutional Amendment against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation necessary, as we have done with race and sex? Is it activist of the Court to decide same-sex marriage, or is it a necessary function of their role as interpreter of the law? These questions may not be answered anytime soon. We can only hope that the judiciary will see to deliver on its duty to uphold the law, as articulated in Marbury v. Madison (1803) by Chief Justice John Marshall “It is emphatically the privilege and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Perhaps, as with other such issues regarding race and sex, the public themselves will eventually seek to change the law so that it coincides with public opinion. As enucleated in Varnum v Brien (2009): We are firmly convinced the exclusion of gay and lesbian people from the institution of civil marriage does not substantially further any important governmental objective. The legislature has excluded a historically disfavored class of persons from a supremely important civil institution without a constitutionally sufficient justification. There is no material fact, genuinely in dispute, that can affect this determination. AFFIRMED. The Defense of 21 References Andersen v. King County, No. 75934-1 138 P.3d 963 (Washington 2006). Baehr v. Miike, No. 91-1394, WL 694235 (Hawaii 1996). Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986). Culhane, J. G. (2008). Beyond rights and morality: The overlooked public health argument for same-sex marriage. Law & Sexuality: A Review of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Legal Issues, 17, 7. Dana, L. R. (2005). Andersen v. King County: The battle for same-sex marriage – Will Washington State be the next to fall? Law & Sexuality: A Review of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Legal Issues, 14, 181. Defense of Marriage Act, Pub. L. No. 104-199, 110 Stat. 2419 (1996). Eaton, S. (2007). Lewis v. Harris: Same-sex marriage is a question for the legislature, not the courts. Law & Sexuality: A Review of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Legal Issues, 16, 157. Goulde, T. R. (2005). In re Kandu: Defending DOMA – Deferential Washington bankruptcy court deals blow to equal protection and due process by upholding federal ban on recognition of same-sex marriage. Law & Sexuality: A Review of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Legal Issues, 14, 193. Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965). Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003). Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967). Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (Cranch 1) 137 (1803). Roche v. McDonald, 275 U.S. 449 (1928). Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996). Shuki-Kunze, J. R. (1998). The ‘defenseless’ marriage act: The constitutionality of the Defense of Marriage Act as an extension of congressional power under the Full Faith and Credit Clause. Case Western Law Review, 48, 351. The Defense of Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987). United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144 (1938). U.S. Const., amend. XIV, § 1. U.S. Const., art. IV, § 1. U.S. Const., art. VI. Varnum v. Brien, No. 07-1499, WL 874044 (Iowa 2009). Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374 (1978). 22