A Short Synopsis of the Education Philosophy

advertisement

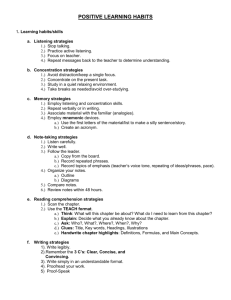

A Short Synopsis of The Educational Philosophy of Charlotte Mason Towards A Philosophy of Education, Volume 6 of the Charlotte Mason Series 1. 2. Children are born persons. They are not born either good or bad, but with possibilities for good and for evil. "This first proposition of Charlotte Mason's educational philosophy may seem merely a statement of the obvious. But it is not some minor element of a greater truth. It is a central truth in its own right, and if we ignore it, great sorrow and malpractice can result. Try a simple experiment. Take a small child on your knee. Respect him. Do not see him as something to prune, form or mold. This is an individual who thinks, acts, and feels. He is a separate human being whose strength lies in who he is, not in who he will become. If his choices now and in the future are to be good ones, this person must understand reality and see the framework of truth... We are told by many in our generation that this small child is a cog in a machine, or even that he is a possession, like a pet animal... We must answer: NO. You are holding a person on your knee and that is wonderful."1 The principles of authority on the one hand, and of obedience on the other, are natural, necessary and fundamental; but3. These principles are limited by the respect due to the personality of children, which must not be encroached upon whether by the direct use of fear or love, suggestion or influence, or by undue play upon any one natural desire 4. "There is an idea abroad that authority makes for tyranny, and that obedience, voluntary or involuntary, is of the nature of slavishness; but authority is, on the contrary, the condition without which liberty does not exist and, except it be abused, is entirely congenial to those on whom it is exercised: we are so made that we like to be ordered even if the ordering be only that of circumstances." "That principle in us which brings us into subjection to authority is docility, teachableness, and that also is universal. If a man in the pride of his heart decline other authority, he will submit himself slavishly to his 'star' or his 'destiny.' It would seem that the exercise of docility is as natural and necessary as that of reason or imagination; and the two principles of authority and docility act in every life precisely as do those two elemental principles which enable the earth to maintain its orbit, the one drawing it towards the sun, the other as constantly driving it into space; between the two, the earth maintains a more or less middle course and the days go on."2 Therefore, we are limited to three educational instruments— the atmosphere of environment, the discipline of habit, and the presentation of living ideas. The P.N.E.U. Motto is: "Education is an atmosphere, a discipline, and a life." 5. 6. Then we say that "education is an atmosphere," we do not mean that a child should be isolated in what may be called a 'childenvironment' especially adapted and prepared, but that we should take into account the educational value of his natural home atmosphere, both as regards persons and things, and should let him live freely among his proper conditions. It stultifies a child to bring down his world to the child's' level. "The atmosphere in which a child gathers his unconscious ideas of right living emanates from his parents. Every look of gentleness and tone of reverence , every word of kindness and act of help, passes into the thought-environment, the very atmosphere which the child breathes; he does not think of these things, may never think of them, but all his life long they excite the vague appetency...towards things sordid or things lovely, things earthly or divine." "In a personal interview with Marion Berry in July 1999, I asked her the secret to creating the atmosphere that seemed to exist in her school for fifty years or more, one in which children thrived as persons in proper relationship to so many things. Her reply came quickly, firmly, and with conviction for her ninety-one years. Yet she spoke of what was omitted rather than what was present. The absence of four toxic practices – competition, prizes and marks, stress, and comparison-purified the air for learning."3 7. By "education is a discipline," we mean the discipline of habits, formed definitely and thoughtfully, whether habits of mind or body. Physiologists tell us of the adaptation of brain structures to habitual lines of thought, i.e., to our habits. " 'The formation of habits is education and education is the formation of habits', Charlotte Mason maintained. But children are often 'left up to their nature' in hopes that they will grow out of it or in excuse of their youth or individuality. But Charlotte Mason was adamant concerning training in habit. She went as far as to say that almost anything could be accomplished through the correct and consistent training...This discipline is training that comprises relationship with oneself, one's world, one's God, and others. The parent and/or teacher supplants the child's weakness or affinity through instruction of conscience and the will. Along with deliberate effort, that is often painstaking on behalf of both the child and the educator to reach the desired outcome. This work expands the scope of a child's education to include the following habits: a. Intellectual habits: attention, concentration, thoroughness, intellectual volition, accuracy, reflection, and meditation, rapid mental effort and application, thinking, imagining, remembering, and perfect execution. b. Moral habits: sweet thought, obedience, truthfulness, reverence, and temper c. Physical habits; self-restraint, self-control, self-discipline, alertness, quick perception, fortitude, service, courage, prudence and chastity. d. Religious habits: the thought of God, a reverent attitude, regularity in devotions, reading the bible, praise and Sunday keeping_ e. Miscellaneous habits: physical exercise, good manners and ear and voice. The children will have habits, and we as parents and educators are engaged in forming these habits actively or passively every day, every hour:14 8. In saying that education is a life,- the need of intellectual and moral as well as of physical sustenance is implied. The mind feeds on ideas, and therefore children should have a generous curriculum. In terms of the development of a curriculum that reflects the idea that education is a life, Miss Mason does not leave us clueing. She has written that just as the body needs nourishment in order to grow and flourish, so does the mind need feeding. “The mind feeds on ideas," she wrote "and therefore children should have a generous curriculum.' The business of teaching was for the sole purpose of furnishing the child with ideas, and any teaching that did not leave the child with a new mental image missed the mark. A morning in which the child receive no new idea, needless to say, was a morning wasted. This wasteful existence goes on and on in many a classroom, on many a day, as the student and the teacher passively interact with information. This need not be, nor should be, as Charlotte Mason has left a rich legacy of thinking and practice that constantly affirms one of her basics tenets. That education is a life. This principle is not a narrow compartmentalizing of facts into one area and life into another, but a rich interweaving of ideas, experiences, knowledge that leads ultimately to the way we all as individuals live our lives.'5 9 We hold that the child's mind is no mere sac to hold ideas; but is rather, if the figure may be allowed, a spiritual organism, with an appetite for all knowledge. This is its proper diet with which it is prepared to deal; and which it can digest and assimilate as the body does foodstuffs. “This vibrant picture at the "life-ward" motivation of children that she draws is most striking and unique. The nature of knowing (learning) begins with ideas, the live things of the mind, that strike, impress, seize, and catch hold of one. Ideas are the initiators of habits, of thought, and habits of action. They originate as the issue from two minds. No one person has the power to produce an idea autonomously, as ideas reproduce after their own kind and in turn generate their own ideas, “Ideas are of spiritual origin, and God has made us so that we get them chiefly as we convey them to one another”. These ideas are conveyed through the natural world, heroic poetry, painted pictures, books of literary tradition, proverbial philosophy, music symphonies, and the lives of persons and nations. Ideas are the living concepts that under gird, give meaning to, and connect one thought to another”6 10. Such a doctrine as e.g. the Herbartian, that the mind is a receptacle, lays the stress of education (the preparation of knowledge in enticing morsels duly ordered) upon the teacher. Children taught on this principle are in danger of receiving much teaching with little knowledge; and the teacher's axiom is. "what a child learns matters less than how he learns it." 11. But we, believe the normal child has powers of mind which fit him to deal with all knowledge proper to him, give him a full and generous curriculum; taking care only that all knowledge offered him is vital, that is, that facts are not presented without their informing ideas. The educators part is to place before the child the daily nourishment of ideas by way of books !hat promote “living thought". Scores of thinkers will meet the children mind to mind in books of literary quality. This "mind food”- is not served up in dry bits, diluted, or pre-digested. Instead it is offered in abundance with all it’s savory delights. Each child eats what he wills and leaves nourished and contented”7 Out of this conception comes our principle that,— 12. "Education is the Science of Relations"; that is that a child has natural relations with a vast number of things and thoughts: so we train him upon physical exercises, nature lore, handicrafts, science and art, and upon many living books, for we know that our business is not to teach him all about anything, but to help him to make valid as many as may be of— "Those first-born affinities That fit our new existence to existing things." We consider that education is the science of relations, or, more fully, that education considers what relations are proper to a human being, and in what ways these several relations can be best established; that a human being comes into the world with a capacity for many relations-, and than we, for our part, have two chief concerns, first, to put him in the right way of forming those relations by presenting the right idea at the right lime, and by forming the right habit upon the right idea: and secondly, by not getting in the way and so preventing the establishment of the very relations we seek to form. "8. 13. In devising a SYLLABUS for a normal child, of whatever social class, three points must be considered: (a) He requires much knowledge, for the mind needs sufficient food as does the body. (b) The knowledge should be various, for sameness in mental diet does not create appetite (i.e. curiosity) (c)knowledge should be communicated in well-chosen language, because his attention responds naturally to what is conveyed in literary form.. 'Charlotte Mason introduces the reader to living books and living things as the only form of "mind food" that provides the daily nourishment for the mind to do its work. "For the truth of the matter is that babies and young children explore new experiences with tireless enthusiasm. A girl or boy has a mind which is hungry for ideas. They have an appetite for knowing and experiencing”. If a book is not living, Mason refers to it as twaddle, something dry, diluted, pre-digested, void of thought. It seems as if there is nothing in between; books and things either do the work of nourishment, or they do not”.9 14. As knowledge is not assimilated until it is reproduced, children children should ‘tell back’after a single reading or hearing; or should write on some part of what they have read. 15. A single reading is insisted on, because children have naturally great power of attention; but this force is dissipated by the re-reading of passages, and also, by questioning, summarizing and the like. Acting upon these and some other points in the behavior of mind, we find that the educability of children is enormously greater than has hitherto been supposed, and is but little dependent on such circumstances as heredity and environment. Nor is the accuracy of this statement limited to clever children or to children of the educated classes: thousands of children in Elementary Schools respond freely to this method, which is based on the behaviour of mind. 'Narration is re-telling. It is not memorizing or parroting. It includes feelings and reactions. It is not word for word, but point for point. It is a type of essay response to a broad open-ended questioning, a recall of information. In the strictest sense, narration is an immediate recall of information seen, read, or heard, In a more liberal sense it is often used as a quest for information that has been seen, read or heard after a period of time in the form of exams or evaluation of a child's knowledge on a particular subject. But even in the latter sense, the work of oral narration must have gone on before in order that the child obtain the knowledge in question”10 16 There are two guides to moral and intellectual selfmanagement to offer to children, which we may can call ‘the way of the will' and 'the way of the reason.' 17 The way of the will: Children should be taught, (a) to distinguish between ‘I want' and ‘I will’ (b) That the way to wilI effectively is to turn our thoughts from that which we desire but do not will. (c) That the best way to turn our thought is to think of or do some quite different thing, entertaining or interesting. (d) That after a little rest in this way, the will returns to its work with new vigour. (This adjunct of the will is familiar to us as diversion, whose office it is to ease us for a time from will effort, that we may ‘will’ again with added power. The use of suggestion as an aid to the will is to be deprecated, as tending to stultify and stereotype character, It would seem that spontaneity is a condition of development, and that human nature needs the discipline of failure a well as of success). "The great things of life, life itself are not easy of definition. The Will, we are told, is ‘the sole practical faculty of man.' But who is to define the Will? we are told again that ‘the Will is the man’ and yet most men go through life without a single definite act of willing. Habit, convention, the customs of the world have done so much for us that we get up, dress, breakfast, follow our morning's occupations, our later relaxations, without an act of choice. For this much at any rate we know about the will. Its function is to choose, to decide, and there seems to be no doubt that the greater becomes the effort of decision the weaker grows the general will. Opinions are provided for us, we take our principles at second or third hand, our habits are suitable, and convenient, and what more is necessary for a decent and orderly life? But the one achievement possible and necessary for every man is character and character is as finely wrought metal beaten into shape and beauty by the repeated and accustomed action of will. We who teach should make it clear to ourselves that our aim in education is less conduct than character; conduct may be arrived at, as we have seen, by indirect routes, but it is of value to the world only as it has its source in character11 “By degrees the scholar will perceive that just as to reign is the distinctive function of a king, so to will is the function of a man. A king is not a king unless he reigns and a rnan is less than a man unless he wills” 12 18. The way of reason: We teach children, too, not to 'lean (too confidently) to their own understanding’; because the function of reason is to give logical demonstration (a) of mathematical truth, (b) of an initial idea, accepted by the will. In the former case, reason is, practically, an infallible guide, but in the latter, it is not always a safe one; for, whether that idea be right or wrong, reason will confirm it by irrefragable proofs. 19. Therefore, children should be taught, as they become mature enough to understand such teaching, that the chief responsibility which rests on them as persons is the acceptance or rejection of ideas. To help them in this choice we give them principles of conduct, and a wide range of the knowledge fitted to them. These principles should save children from some of the loose thinking and heedless action which cause most of us to live at a lower level than we need. “After abundant practice in reasoning and tracing out the reasons of others, whether in fact or fiction, children may readily be brought to the conclusions that reasonable and right are not synonymous terms; that reason is their servant, not their ruler, - one of those servants which help Mansoul in the governance of his kingdom. But no more than appetite, ambition, or the love of ease, is reason to be trusted with the government of a man, much less that of a state; because well reasoned arguments are brought into play for a wrong course as for a right. He will see that reason works involuntarily; that all the beautiful steps follow one another in his mind without any activity or intention on his own part; but he need never suppose that he was hurried along into evil by thoughts which he could not help, because reason never begins it. It is only when he chooses to think about some course or plan, as Eve standing before the apples, that reason comes into play; so, if he chooses to think about a purpose that is good, many excellent reasons will hurry up to support him; but, alas, if he choose to entertain a wrong notion, he, as is were, rings the bell for reason, which enforces his wrong intention with a score of arguments proving that wrong is right. '13 20. We allow no separation to grow up between the intellectual and 'spiritual' life of children, but teach them that the Divine Spirit has constant access to their spirits, and their Continual Helper in all the interests, duties and joys of life. "Supposing we are willing to make this great recognition, to engage ourselves to accept and invite the daily, hourly, incessant co-operation of the divine Spirit, in, to put it definitely and plainly, the schoolroom work of our children, how must we shape our own conduct to make this cooperation active, or even possible? We are told that the Spirit is life; therefore, that which is dead, dry as dust, mere bare bones, can have no affinity with Him, can do no other than smother and deaden his vitalizing influences. A first condition of this vitalizing teaching is that all the thought we offer to our children shall be living thought; no mere dry summaries of facts will do; given the vitalizing idea, children will readily hang the mere facts upon the idea as upon a peg capable of sustaining all that it is needful to retain. We begin by believing in the children as spiritual beings of unmeasured powers-intellectual, moral, spiritual – capable of receiving and constantly enjoying intuitions from the intimate converse of the Divine Spirit”14 References: 1. Jack Beckman, When Children Love to Learn, p51 2. Charlotte Mason, Vol 1, CH4 3. Charlotte Mason, Home Education, Vol 1 4. Maryellen St Cyr, When Children Love to Learn, p90-91 5. Maryellen St Cyr, When Children Love to Learn, p100 6. Maryellen St Cyr, When Children Love to Learn, p101 7. Maryellen St Cyr, When Children Love to Learn, p102 8. Jack Beckman, When Children Love to Learn, p123 9. Maryellen St Cyr, When Children Love to Learn, p125 10. Maryellen St Cyr, When Children Love to Learn, p128 11. Charlotte Mason, Vol 6, p128,129 12. Charlotte Mason, Vol 6, p133 13. Charlotte Mason, Vol 1, CH9 14. Charlotte Mason, Vol 2, p277