Theory and Criticism: From Plato to Ransom

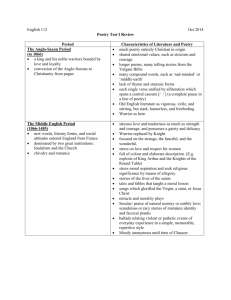

advertisement

Theory and Criticism: From Plato to Ransom Summarized and compiled by the members of English 449 at Lycoming College in the Spring Semester 2002: Gretchen Hause, Laura Koons, Elizabeth McNassor, Casey Spencer, Holly Wendt CLASSICAL CRITICISM Plato (427-347 BC) Republic Plato was influenced by Socrates and utilized a dialogue form in writing due to this influence. He argues that poetry was a “divine madness,” not a skill that a person could learn. He thought that poetry must be instructive and act as a moral tool. Plato also argued that poetry was imitative, or mimetic, and therefore poetry as a moral tool is impossible because poetry should never imitate anything “untrue,” that might be a negative example. Plato thought that all poetry was untrue because it is three times removed from the original form. He illustrates this point in his famous Allegory of the Cave. Aristotle (384-322 BC) Poetics, Rhetoric Aristotle believed that people are basically imitative. Through imitation, they learn lessons even if the lesson is painful. The purpose of drama is to arouse fear and pity in the audience and purge the audience of these emotions, the result of which is known as catharsis. He believed that this catharsis made people emotionally stronger. He believed in the three Unities (time, action, and place). The Unity of Action mandates that there should be no subplots and only one main lesson. The Unity of Time suggests that everything should progress in real world time. The Unity of Place says that the action should happen in the same place, or very close to it. Horace (65-8 BCE) Ars Poetica Horace viewed poetry as both an art and a craft. Horace firmly believed that poetry ought to both instruct and delight. He established some guidelines for both poetry and drama. He thought that poetry ought to have unity and consistency, that it ought to stick to a particular subject. He thought that meter and language should fit both subject and character. He felt that a poet ought to write what they know and draw from his life experience. Horace said that a poet should not try to impress, but rather inform and entertain. He thought that so far as myths were concerned, one ought either to follow tradition or invent something new. Horace believed that a play should put an audience directly into the action and should not tell the entire story on stage. The play should consist of five acts. Horace believed that one should not employ “deus ex machina” as a quick fix for conflict resolution, solving conflicts by means of the gods. He also believed that the chorus should play an important role in the play. Longinus (first century CE) On Sublimity Longinus’s On Sublimity discusses the idea of the sublime. He argues that sublimity is not just lofty, elevated writing, but rather something that comes from an inner genius or passion. He argues that there are five sources of sublimity, two from natural sources, and two from artistic sources. He states that the sublime comes from the power to conceive great thoughts (natural). He also thinks that the sublime comes from a strong or inspired emotion (natural). Artistically, he thinks that the sublime comes from certain figures of speech or thought. He also thinks that noble diction, use of metaphor, and dignified or elevated word arrangement contribute to the sublime. Sublimity is a work that implies that man can transcend the limits of the human condition, and a realization that there is something more to life than the mundane. Quintillian (30-100) Institutio Oratoria Quintillian discusses tropes, which are an “artistic alteration of a word or phrase from its proper meaning to another.” He argues that some of these tropes aid meaning, and some are merely ornamental. He discusses the use of metaphor, synecdoche (a figure of speech in which part is used for a whole), and metonymy (a figure of speech which replaces a word with an object with which it is closely associated) to create these tropes. He also discusses the use of figures, which are different from tropes because they “do not necessarily involve any alteration of the order or strict sense of words.” He discusses the figure of thought (a conception in the mind), and the figure of speech (an expression of thought which includes words, diction, expression, style or language). He says that irony can be associated either with tropes or figures. He also believes that a poet’s work ought to be moral and teach virtue. MEDIEVAL CRITICISM St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) On Christian Doctrine, The Trinity St. Augustine’s primary concern was biblical text. He compared the difference between the figurative and literal interpretations of the text and preferred the figurative. He thought that things did not signify, but signs did. Signs could either be natural (which signifies without intending to, such as smoke signifying fire), or conventional (where words convey ideas). Conventional signs can be literal (such as the word “ox” which signifies a four legged farm animal), or figurative (which uses a metaphor of an ox to represent something else). Thought is the ideal form, followed by spoken words, which signify ideas, and then the written word which is a symbol of spoken word. Only through signs and metaphors can we begin to express the perfect idea (to St. Augustine, the Word of God). We can’t describe all things, but we can relate them to something for deeper understanding. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) Summa Theologica Aquinas used a unique form of argument. He would first pose a yes or no question, and then offer possible arguments for the “no” position. After that, he would pose his “yes” argument and support it. He argued that figurative language serves no function but to disguise the truth. He struggled to understand why biblical texts used this “murky” language. He thought all interpretations of biblical texts ought to be literal. Dante Aligheri (1265-1321) Il Convivio Dante was a proponent of literature in the vernacular, or national, language. He that that poetic language was polysemous, open to many interpretations. He adapted a four-step exegesis interpretation to poetry and thought that all interpretations could exist at once, but a literal interpretation must always be first. He thought that poetry must be a moral, instructive tool. Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) Genealogy of the Gentile Gods Boccaccio believed that poetry proceeded from the “bosom of God,” and that a poet could not be created because poetry is innate. He thought that poets were not necessarily liars, but they veiled the truth in fiction. Boccacio believed that poetry was sublime in its effects. It is not the poet’s function to be easy to read or familiar. Boccaccio believed that through working at poetry, a reader would appreciate it more. Christine de Pizan (1365-1429) The Book of the City of Ladies De Pizan prefigures many of the main issues in feminism, which will appear several centuries after her work. She discusses the misogynist views of her day, and creates a society where a person can be accepted for her ideas. She believes that men should embrace the ideas of intelligent women, and she does not think that ignorance is an excuse for wrong ideas. She thinks that arguments should be based in Reason. RENAISSANCE CRITICISM Giambattista Giraldi (1504-1573) Discourse on the Composition of Romances Giraldi was a proponent of the vernacular and national literature. He believed that poetry should conform to the language it is written in; Tuscan poetry will not be the same as Greek. He also believed that social conditions could change literature and the context of criticism. A modern critic, Giraldi disliked excessive allegorizing and was skeptical of the four-step exegesis interpretation. He was also an innovator of Renaissance Romance and depicted the “obscene” (murder, etc.) on stage. In direct opposition to Aristotle, he said that multiple plots in literature are like a wellproportioned body. He said that poetry should be moral, beautiful - with emphasis on each part not only the whole--and follow models already utilized in a particular genre. Joachim du Bellay (1522-1560) The Defense and Illustration of the French Language Du Bellay asserts that all language has one purpose: to signify the mind’s conceptions. Some languages, however, aren’t as rich as others. The French language isn’t as rich as the Latin or Greek because of “the ignorance of our ancestors.” The French left out the ornaments of the classical languages; the language is like a plant that has not yet flowered. He also believes that translations are insufficient in portraying the original. A translator may serve those who don’t know the language, but the delivery or speech cannot convey the emotion. He states that the improvement of the French language cannot happen without the doctrine that comes from the Greek and Romans. Pierre de Ronsard (1524-1585) “A Brief on the Art of French Poetry” In this work, Ronsard gives instructions for writing poetry and how the poet should live. He states that poetry can’t be taught or learned by rules; that poets are inspired by the divine. Poets communicate with the divine and translate and embellish it so others can understand. Ronsard instructs poets to act kindly and honorably, study the good poets, excuse no faults of their own, converse with fellow poets of the day, know their own language, and learn about other trades. He states that the invention, or aim, of the poet is to imitate, invent, and represent things, which are or may be, in resemblance to truth. Poetry should be better than the vulgar, but intelligible to everyone else. A poet should have good disposition, or “proper placing and ordering of the things invented.” A poet should also use good elocution (always using the appropriate word), and attend to invention rather than rhyme. The skilled poet needs to ignore his audience; it is “better to be in the service of truth than in the service of opinion.” Giacopo Mazzoni (1548-1598) On the Defense of the Comedy of Dante Mazzoni believed that there were three types of objects: the idea (art of horsemanship - the ruling art), the work (art of bridle making - fabricating art), and the idol (painting the bridle - imitative art). He placed poetry into the category of idolistic art. He also said that poetry could be portrayed in two ways. Phantastic, or imaginary, poetry was truth veiled with fiction. Icastic, or realistic, poetry dealt with the true actions of real people in a credible manner. Finally, Mazzoni asserted that different types of art all have their place; comic for the appetite, heroic for the spirit, and tragic for reason. Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586) An Apology for Poetry Sidney is not interested in the rules or rhetoric of poetry; he sees it as an art form. He states that there is no better way to spend one’s time then poetry because it teaches and moves the best. He also stresses that poets are not liars because the poet “affirms nothing and therefore never lieth.” He believes that poetry does not corrupt man, man corrupts poetry. Answering to Plato’s objections to poetry, Sidney argues that poets are makers, men who use their mind to improve on what they see. Historians only concern themselves with what is, and the ideas of philosophers are obscure. Because poets write what may and should be, they are closer to the ideal forms than others. ENLIGHTENMENT CRITICISM John Dryden (1631-1700) An Essay of Dramatic Poesy, Preface to Troilus and Cressida, and Preface to Sylvae Dryden believes the purpose of tragedy, which comes from fear and pity, is to purge our emotions. To “instruct delightfully” is the purpose of all poetry. Through examples, tragedy does this and is thus superior to philosophy and history. The poetic hero must possess some “natural goodness.” In discussing translations, Dryden says the translator’s job is to make the author as charming as possible. He must understand the mother language before he translates, or it won’t be graceful. Joseph Addison (1672-1719) The Spectator, No. 62 & 412 In The Spectator, No. 62, Addison discusses the idea of wit. Wit brings ideas together, while judgment separates them. Addison says wit must delight and surprise, combining ideas dissimilar in nature. Addison has a negative view of false wit, or resemblance of words such as word play and puns. He also mentions mixed wit, which is part resemblance of ideas and part resemblance of words - a pun in a larger witty idea. In The Spectator, No. 412, Addison is concerned with imagination and beauty. He says that things outside ourselves bring pleasure through the senses and “new and uncommon” things break the monotony of life. In discussing beauty, Addison states “nothing…makes its way more directly to the soul.” Beauty “strikes the mind with an inward joy, and spreads a cheerfulness and delight.” Art can accomplish this same effect by reminding the reader of an initial experience with beauty. Alexander Pope (1688-1744) An Essay on Criticism Pope states that criticism has strayed too far from the Greek and Roman past; it should return to the classics. Critics should use nature as a frame of judgment because it is universal. Truth comes from reason and critics should seek the truth in a work. Pope also says that a work should be moral, and that for every work, there is a “perfect” critic who will see all parts as they contribute to the whole (not just parts and fragments). Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) The Rambler, No. 4 [On Fiction], “Preface to Shakespeare,” “Lives of the English Poets [On Metaphysical Wit]” Johnson feels that fiction is a moral learning tool. “Bad” characters should never be presented and vice should always horrify and elicit disgust. Familiar histories are more useful as teaching tools than grander schemes and metaphors. In Preface to Shakespeare, Johnson says that nothing can be judged until it is compared with like works. Shakespeare is the “poet of nature”, using practical examples to instruct by pleasing. He has no heroes, but fully human characters; he approximates the remote and familiarizes the wonderful. In Lives of the English Poets, he says that wit must change with fashion. Though ideas are often new, they are seldom natural. One cannot be born a metaphysical poet--it is a man-made construct. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) Critique of Judgment Kant focused on beauty, both on what makes something beautiful and the standards for recognizing the beautiful. The beautiful mixes both the sensible and nonsensible on an objective level, as opposed to something which is “good” (useful) or “agreeable” (a matter of personal preference). Kant states that beauty brings together imagination (nature) and reason (mind) and is therefore superior to the sublime because beauty cannot be explained or reasoned; the sublime separates, rather than unites, the mind and nature. Also, because of beauty's superior nature, it should always be moral and never tainted with mundane purposes. Edmund Burke (1729-1797) A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful Burke believed there should be a basic standard of taste. Senses perceive things in the same way, and imagination can only vary and interpret what it is given by the senses. Therefore, natural taste should be the same for everyone. It is acquired taste that differs. Burke was also interested in the philosophical and physical nature of the human response to the exalted and fearful in both art and nature. He felt the sublime was different from beauty in that it produced the strongest emotion in which the mind is capable of feeling, including fear and terror. Beauty is small and finite, whereas the sublime is intense and awe inspiring. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781) Laocoön In Laocoön, Lessing examined the relationship between painting and poetry, arriving at the conclusion that the two are alike in aim and effect but differ in means (visual vs. verbal). Like Aristotle, Lessing agreed that poetry should draw on action, not imitation of forms, as poetry is an art of time, not space, as is painting. Painting can imitate action, but only through bodies; poetry can imitate bodies, but only through action. He believed truth to be greater than beauty, and realized that it was sometimes necessary to sacrifice beauty in order to represent the truth more clearly. Friedrich von Schiller (1759-1805) On the Aesthetic Education of Man In the letters that comprise On the Aesthetic Education of Man, Schiller asks the question of whether one can concern oneself with art when politics are unstable. However, he believed that politics could be righted by the understanding of the beautiful (aesthetics). He also questioned whether man was turning away from Nature/Imagination to Reason while noting that the Moderns focus on one specialized field, while the Greeks considered the whole and universal, not limiting one person to one field of study. Finally, concerning the nature of art, Schiller proposed that art comes from a better, higher place and is therefore “immune to human arbitrariness.” Because art does represent something of a higher power, it is therefore the artist’s duty to ignore the opinion of the times and direct humanity toward good. ROMANTIC CRITICISM Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) Phenomenology of Spirit; Lectures on Fine Art In Hegel's Phenomenology, he used the dialectic to arrive at truth through the consideration of a thesis, development of an antithesis, and a union of the two in a synthesis. He concentrates on the idea of “self,” in which we determine our “selfconsciousness” by meeting something that is “not-self,” i.e. another person, because it is only through relationships with others do we have a “self.” Hegel illustrates this with his Slave/Master relationship: the Master demands recognition from the Slave, but refuses to give recognition to others. Since recognition is only valuable when given freely, the Master feels doubt in his “self-hood.” In reality, the Master's “self-hood” is mediated by the Slave and the Slave is an independent entity. This arrives at the synthesis that each person is a self, and there must be mutual recognition/acknowledgement to have “selfhood.” In Lectures on Fine Art, Hegel also touches on consciousness, but here on the consciousness of the “spirit,” which can only be reached by philosophy. Art gives this “spirit” a concrete form. Art is divided into categories: symbolic art, which is tied to nature but falls short of the sublime and therefore fails; classical art, which focuses on the human form and fails because it defines “spirit” as something particular and human; and Romantic art, which moves both artist and audience to an “inwardness of selfconsciousness” and therefore reaches sublimity and succeeds. Because of his focus on art as the reflection of the inner spirit, Hegel is considered the champion of the Romantics. William Wordsworth (1770-1850) Preface to Lyrical Ballads The major focus of Wordsworth revolved around his view of poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” Because of this, poetry should break from rules in favor of inspiration from emotions and refrain from being technical; poets should write in the common language instead of elevated speech, as prose with meter. For subject matter, the poet should look to the common man because the emotions of the common man are more powerful- "raw simplicity." Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) A Defence of Poetry Shelley wrote his Defence of Poetry in refutation of The Four Ages of Poetry by Peacock. He believed that the poet, although he transcends time, is judged by his contemporaries; nonetheless, the poet should not be a servant to politics/times but should introduce new ideas arranged and ordered in a beautiful way. By the same token, he attributed poetry to divine inspiration (moral tool), but because of the nature of language, the full essence of the divinity can't be transcribed onto paper. Poetry is infinite, of many layers, and therefore poetry will endure. Shelley also referred to the utility of poetry; it produces both durable and transitory pleasure, the former of which cannot be defined, yet should be the kind produced by poetry. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) “The American Scholar;” “The Poet” In The American Scholar, Emerson discussed the role of the books of the past, saying that the spirit of the scholar is influenced by works of the past; the best of those propel us toward the truth, but books cannot convey truth. Therefore, each age must write its own books to propel society toward truth, which humans naturally seek. However, he cautions that literary works are not perfect and our love of our heroes may be deluding. In The Poet, Emerson states that the poet is representative of complete men, half as himself and half as expression. He is a natural “sayer” (represents and delivers beauty to the people), and once that beauty is expressed, it becomes a new and higher beauty. Symbols also express beauty, so we are all essentially poets because we all use symbols. “We are symbols.” The poet can help us get closer to the truth; ascension is the aim of poetry. Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) “The Philosophy of Composition” For Poe, the overall effect of a poem is of the utmost importance, and similarly, beauty is not a quality of a work, but an effect of the whole. In his search for the ideal poem, Poe set out some guidelines: 1) the appropriate work can be read in one sitting, about 108 lines 2) the use of a refrain and the monotone are good things to utilize in poetry 3) the sounds of “o” and “r” are the most agreeable 4) a sad tone is the most beautiful kind, and the death of a beautiful woman is both the most poetic and beautiful subject for a poem, and, finally, 5) the poet should compose his ending first so that he knows where he is going with the poem. VICTORIAN CRITICISM Karl Marx (1818-1883) and Frederich Engels (1820-1895) Marx and Engels did not directly deal with literary theory or criticism; their work was more a social comment that leads to Marxist Criticism (among other things). They argue against a capitalist society and examine the condition of the people caught in its clutches. They are concerned with the materialistic state of society. They talk about the danger of symbolic wealth (money), and the danger of symbolic wealth becoming more valuable than goods. In pre-industrial times, people bartered goods to get food and other goods, and everyone made their goods themselves. In that society, symbolic wealth was not very important, but with industrialization, the bartering system broke down. Symbolic wealth causes huge differences between wealth and poverty. People started working in factories on assembly lines only making part of a good. They could not even hold up a manufactured item and say that they made it. Workers were oppressed, and Marx and Engels empathized with their condition. They argued that for every luxury the bourgeoisie enjoys, another human suffers. Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) “The Painter of Modern Life” The painter’s concern is the present and not the past. Beauty is a double composition. It is made of the eternal element that is hard to label and the relative/circumstantial element, consisting of the age (current religion, culture, fashion). Beauty must contain these two elements. “Genius is recovered childhood at will.” This artist (the “anonymous” Guys) sees everything in a state of newness. This man is a spectator of life--and searching for modernity. The body doesn’t mirror the soul; dress your subjects in garments of the present. The dandy is positive because he is an item of the times--a distinct person searching for personal originality. Cosmetics are also good! Nature gives us both positive and negative instincts, so we have reason to guard against some of nature’s negative instincts. Thus, religion and nature are artificial, just like make-up. Face painting represents life. Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time;” Culture and Anarchy Matthew Arnold believed foremost that the critic should "see the object as in itself it really is," and do so in a disinterested (objective) way in order to know and spread the best ideas and thought throughout the world. This included refuting all existing religious works in order to reach for the ideal, not accepting less than perfection. Arnold placed the creative process as the highest function of man, but criticism fills in when creative works are not possible; atmosphere influences the creative process immensely (Elizabethan England, Pericles' Athens). In Culture and Anarchy, Arnold examines the idea of culture as the study of perfection, focusing on a harmony over all beauty and human worth without emphasizing one thing over another. Walter Pater (1839-1894) Studies in the History of the Renaissance Pater coined the phrase “art for art's sake.” He thought that the most important quality a critic must have is not to posses some abstract definition of beauty but to posses the power of being deeply moved by beautiful things. The function of the aesthetic critic is to determine what virtue something has that makes it beautiful and under what conditions that beauty is experienced. Renaissance art was an “outbreak of human spirit,” and the artists of this era did not live isolated lives but “breathed common air, and caught light and heat from each other's thoughts.” Theories should not take away the enjoyment of art; we should always be seeking the beautiful. Stephane Mallarmé (1842-1898) “Crisis in Poetry” Mallarmé believed that literature was in a time of crisis. Poetry and prose is the same thing: “There is verse as soon as diction is stressed; there is rhythm as soon as style is emphasized.” Poetry goes through periods of “gleaming” and “fading” and is constantly changing, or “recasting.” Beauty of traditional forms is still valid on “important occasions.” Language is imperfect and the sound of words does not always match the meaning. Poetry is “an attempt to make up for the failure of language.” Realism cannot fully express reality; speech is allusion. You must divorce the author from work. Henry James (1843-1916) “The Art of Fiction” James believed that art, both the fiction and author, should never apologize for itself. Art should never concede that it is fictitious because the aim of fiction is to represent life. “Literature should be either instructive or amusing.” The novel ought to be “good” but it is impossible to define “good” in the moral sense. We can only demand that literature be interesting and not morally edifying. The only way to create good art is it so give it complete freedom. Characters should be realistic. The writer should work from experience as much as possible. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) “On Truth and Lying in a Non-Moral Sense” Human intellect is purposeless within nature; it is only important to humans. Truth is a way of designating that something is the same everywhere. Language allows people to perform this manipulation and to lie. Humans desire only the pleasant consequences of truth, not truth itself. Language is a mere copy of nervous stimulations and sounds and is arbitrary--it cannot express true forms. For example: What is the meaning of the word leaf? All leaves are different; the word and concept of leaf is made by dropping the differences between them. Therefore, a word can never fully express reality. Truths are illusions. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) Preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray; “The Critic As Artist” The artist creates beautiful things. There is “no such thing as a moral or immoral book.” All art is useless. In “The Critic as Artist,” Wilde said that criticism breeds new forms, or creation “repeats itself.” It is NOT easier to talk about something than to do something. Criticism is an art, both creative and independent. The critic “works with new materials and puts them into a form that is at once new and delightful.” Criticism is not expressible, but impressive. The critic can bring to beauty whatever one likes, and each art has a critic (music, acting, etc.). People will turn to criticism rather than art. Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) Course in General Linguistics De Saussure's theory rested in language, divided into three parts: 1) le language, or “body language,” 2) la langue, or the specific name given to a language (the English language), 3) la parole, or speech. Language as we know it can only exist as part of a “social contract,” otherwise the signifiers (words) represent different signifies (object) to each person, or mean nothing at all. Because of this, language or linguistic signs must be studied independently of speaking because language can be classified as human phenomena. The linguistic sign (signifier) is NOT Adamic, simply giving names to things, nor does it resemble the thing it signifies but rather unites a concept and sound- image. Because words represent concepts, only language can give shape/order to thought, and only by using words can thought be coherent. De Saussure also touched on the idea of synonyms in that they limit each other to specific shades of meaning. However, de Saussure’s main point is that in languages there are only differences. Sigmund Freud (1865-1939) The Interpretation of Dreams, “The ‘Uncanny,’” “Fetishism” As children we love one parent and hate another (Oedipus complex). Oedipus is a tragedy of destiny because its perseverance as a drama exists in our recognition of the force of destiny--in other words, we each relate to Oedipus. Our dreams convince us this is true; we have the same desire/hate has Oedipus. Freud analyzes Hamlet's procrastination as an Oedipus complex. The meaning of dreams is found in the latent content (dream meaning) and not manifest content (dream action). Within our dreams, condensation, displacement and representation occurs, which all act to repress the latent content or true meaning. “Uncanny” means homely or familiar or concealed/secret. Freud associates this with repression. Freud uses this definition to analyze “The Sandman,” a story in which a young man, Nathaniel, is told his eyes will be stolen in the night if he doesn't sleep. Freud claims that Nathaniel actually has a castration complex. Fetishism results from representation. Some men cannot accept that their mother does not have a penis, so they will create “representatives”--hair, fingers--which function as a sexual organ. WEB DuBois (1868-1963) “Criteria of Negro Art” DuBois did not “care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda.” He believed that the main purpose of art was propaganda. He believed that an artist should use beauty as a way to expose truth to set the world right, and the eternal and perfect beauty was above truth. He believed that the world was distorted away from beauty, and that the variety and possibility of beauty was endless. He gave four very different examples of what is beautiful (architecture, art, nature, and music); suggesting that beauty can be seen in all things, and therefore, everything has the possibility of being art. He says that the “artist's tools” are truth and goodness. He calls truth the “highest handmaid of imagination,” and argues (like Shelley) that it is the greatest vehicle of understanding. He says that goodness leads to justice, honor, and what is “right.” He says that it should be used to gain sympathy of human interest, not just integration of races, but a fuller understanding of the condition of fellow man. Carl Jung (1875-1961) “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry” The practice of art is a psychological activity and can be approached from the psychological angle. Only the artistic process, not the outcome, can be analyzed in this way. Poetry is currently interpreted on an elementary level. For example, just because a poet writes about his personal relationships does not mean we understand all of his poetry. Jung claims that Freud’s technique is based only on what we repress, but Jung believes repression is normal and Freud incorrectly calls clues pointing to the unconscious symbols. The symbol is an intuitive idea--an expression. A symbol is always a challenge. When the poet is controlled by the unconscious, symbols are denser. The source of art is the “collective unconscious,”--the “inborn possibility of ideas.” Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) Literature and Revolution Trotsky believed that art was not self-contained, or separate from politics of political--art is a matter of ideology. He commented against formalism and futurism. He criticized formalists for being narrow and superficial. He argued that futurists are disconnected from the social aspects of the time. He thought it is important that new cultural movements should not reject history and the culture of the past, but that they must use it to grow in tradition. He believed that through Marxism we can gain an explanation of the origins of trends and developments in the arts. His biggest contribution to Marxism is his idea of “permanent revolution.” The idea behind this is that in order for a revolution to succeed, it cannot occur in only one country. In order for a revolution to be successful, it must “spill over” to other nations as well. MODERNIST CRITICISM Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) A Room of One's Own What if Shakespeare had a gifted sister? Woolf explains that she wouldn't be allowed to use her talent and would eventually kill herself. Women who were probably creative geniuses were considered possessed or witches. Women in literature are seen through their relationships with/to men. This “impoverish[es] literature.” Most of the great works would be impossible if men were seen only through their relationship with/to women. There are “two sexes in the mind corresponding to the two sexes in the body.” A normal state of being is when these two sexes exist comfortable together in the mind. Men typically only write with the “male side.” Poetry should have a “mother and as well as a father.” Gyorgy Lukács (1885-1971) “Realism in Balance” Lukács was a Marxist aesthetic. He was critical of capitalism; he believed capitalism drives social elements apart toward independence. Expressionism and Impressionism focus only on “immediate sense of perceptions” and have become a “passive depiction of alimentation under capitalism.” Literature should work to bring to light social problems and possible solutions--realist literature does this. Literature should create representative, “type” characters. Great realist authors (i.e. Shakespeare) should be accessible to everyone. T. S. Elliot (1888-1965) “Tradition and the Individual Talent;” “The Metaphysical Poets” In “Tradition,” Elliot emphasizes that tradition is NOT static, but that things that have worked, been proven, need to be remade in a fresh way. Tradition also encompasses the “historical sense,” or a perception of the “pastness of the past,” in which a writer must write with all of the ages in the back of his mind; however, the writer's own times must also play a part in his work. Art must change with social conditions, yet cannot exist alone; it must always be judged in comparison with all works previously done. Art for Elliot is the “extinction of personality.” In “The Metaphysical Poets,” Elliot spends much of his time refuting Johnson's claim that the metaphysics yoke together ideas that are simply too incongruous to be poetic, stating that though Johnson may be right at times, much of the metaphysical poetry is clear and elegant. Elliot especially praises Donne and Racine for looking into “the heart, cerebral cortex, nervous system, etc,” (they dug deep). However, Elliot does respect Johnson's era, stating that Johnson's critiques stand as part of Johnson's time and context. John Crowe Ransom (1888-1974) “Criticism, Inc.” There are three “trained performers” who have what the critic needs. First, the artist is able to recognize “good art” and his understanding is intuitive. Second, the philosopher must be able to understand the function of arts. Third, the university professor will lead critical activity. Crowe emphasized “the text itself!” Critics must eliminate five things from their criticism: personal registrations, synopsis and paraphrase, historical studies, linguistic studies, and moral studies.