Benefits of physical activity during pregnancy

advertisement

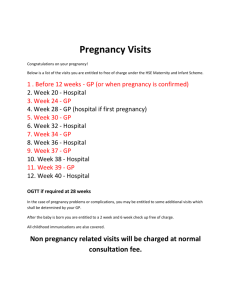

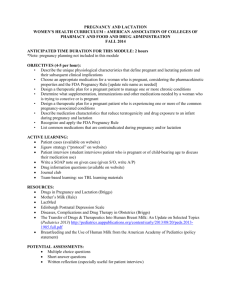

CONSULTATION DRAFT 9.2 Physical activity Regular low to moderate-intensity physical activity is generally safe during pregnancy with likely benefits for mother and baby. 9.2.1 Background Physical activity can be defined as any body movement that involves the use of one or more large muscle groups and raises the heart rate. This includes sport, exercise and recreational activities and incidental activity that accrues throughout the day (eg walking to the shops, climbing stairs). The Australian National Physical Activity Guidelines recommend at least 30 minutes of moderateintensity physical activity on most, preferably all, days, for all adults (DoHA 1999). Moderate-intensity activity is that which causes a slight, but noticeable, increase in breathing and heart rate (eg brisk walking, mowing the lawn, digging in the garden, or medium-paced swimming). The National Physical Activity Guidelines recommend against vigorous activity during pregnancy (DoHA 1999). Levels of physical activity in Australia Data specific to pregnant women are not available but results from national surveys give some indication of patterns of physical activity and sedentary behaviour. • The 2007–08 National Health Survey showed that only 38% of adult women exercised sufficiently to obtain health benefits (AIHW 2011), 34% were sedentary (no exercise or very low levels) and physical activity decreased with age — 29% of women aged 15–24 years were sedentary (AIHW 2010). • People living outside major cities and in more disadvantaged areas were more likely to be inactive (AIHW 2011). • The proportion of people with no or low levels of exercise varied with region of birth — North Africa and the Middle East (91%), South-East Asia (79.1%), Southern and Eastern Europe (74.9%), Australia (71.3%) (AIHW 2010). • In the 2004–05 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 75% of respondents aged 15 years and over living in non-remote areas had sedentary or low levels of physical activity, with women more likely to be sedentary than men (AIHW 2010). Factors influencing levels of physical activity Women may not be involved in physical activity for a range of reasons, including: • perceptions that being physically active may harm the baby; • limited facilities (eg pools, gymnasiums) or infrastructure (eg walking paths), particularly in some rural areas (NRHA 2011); • limited access to group activities and/or facilities specifically for women; • costs of attending activities; • perceptions that being physically active for the sake of it is a waste of time and money; • limited time for physical activity due to other commitments (eg looking after other children, working); and • perception of personal safety in public places. CONSULTATION DRAFT 9.2.2 Discussing physical activity Summary of the evidence Guidelines in the United States (ACOG 2002), Canada (Davies et al 2003), the United Kingdom (RCOG 2006) recommend that women be encouraged to participate in physical activity during pregnancy. Benefits of physical activity during pregnancy Systematic reviews and RCTs have found that regular physical activity during pregnancy: • appears to improve (or maintain) physical fitness (Kramer & McDonald 2006; Ramírez-Vélez et al 2011); • improves health-related quality of life (Montoya Arizabaleta et al 2010) and maternal perception of health status (Barakat et al 2011); and • may reduce depressive symptoms (Robledo-Colonia et al 2012); and • pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy can prevent urinary incontinence (Boyle et al 2012). The evidence on the effect of physical activity on weight gain during pregnancy is inconsistent: • systematic reviews have found: — insufficient evidence to recommend any intervention for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy (Muktabhant et al 2012); — physical activity alone was only effective in reducing weight gain among women who were overweight or obese (Sui et al 2012); and — diet-based interventions were more effective in reducing gestational weight gain than physical activity or a combined intervention (Thangaratinam et al 2012). • RCTs have found that physical activity alone may limit gestational weight gain among women who are overweight or obese (Nascimento et al 2011) and, combined with nutrition intervention, may limit weight gain in women with a pre-pregnancy BMI in the normal range (Ruchat et al 2012) and in the overweight or obese range (Vinter et al 2011). There is insufficient evidence for reliable conclusions about the effect of physical activity on: • maternal and fetal outcomes (Kramer & McDonald 2006); • preventing gestational diabetes or glucose intolerance in pregnancy (Han et al 2012); • improving glucose tolerance in women with gestational diabetes (Ceysens et al 2006); or • preventing pre-eclampsia and its complications (Meher & Duley 2006). RCTs into specific types of physical activity during pregnancy have found: • specifically designed exercise programs prevented pelvic girdle pain (n=301)(Morkved et al 2007) and reduced severity of back pain (Kashanian et al 2009); and • yoga reduced perceived stress (n=90)(Satyapriya et al 2009), improved quality of life and enhanced interpersonal relationships (n=102)(Rakhshani et al 2010) and women reported less pain during labour (n=74)(Chuntharapat et al 2008). The safety of moderate physical activity during pregnancy is supported by a number of RCTs: • walking, joint mobilisation and light resistance exercises (three 35-minute sessions a week in the second and third trimester) (n=160) did not affect fetal cardiovascular responses (Barakat et al 2010), maternal anaemia (Barakat et al 2009a), type of birth (Barakat 2009b), gestational age at birth (Barakat et al 2008) or the newborn’s body size or overall health (Barakat et al 2009c); • aerobic dance exercise was not associated with reduction in birth weight, preterm birth rate or neonatal wellbeing (Haakstad & Bø 2011); • stationary cycling (up to five 40-minute sessions a week from 20 weeks gestation) (n=84) was associated with normalisation of birth weight (Hopkins et al 2010); and • water aerobics (three 50-minute sessions a week from 16–20 weeks gestation) (n=71) was not associated with any alteration in maternal body composition, type of birth, preterm birth rate, neonatal wellbeing or weight (Cavalcante et al 2009). CONSULTATION DRAFT Recommendation 28 Grade B Advise women that low to moderate-intensity physical activity during pregnancy is associated with a range of health benefits and is not associated with adverse outcomes. Pregnant women should avoid physical activity that involves the risk of abdominal trauma, falls or excessive joint stress, such as in high impact sports, contact sports and vigorous racquet sports (NICE 2008). They are also recommended not to scuba dive, because the risk of birth defects seems to be greater among those who do, and there is a serious risk of fetal decompression disease (Camporesi 1996). 9.2.3 Practice summary: physical activity When: All antenatal visits. Who: Midwife; GP; obstetrician; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioner; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker; multicultural health worker, physiotherapist. Assess levels of activity: Ask women about their current levels of physical activity, including the amount of time spent being active and the intensity of activity. Provide advice: Explain the benefits of regular physical activity. Give examples of activities that are of sufficient intensity to achieve health benefits (eg brisk walking, swimming, cycling). Advise women to discuss their plans with a health professional before starting or continuing a program of physical activity. Provide information: Give information about local supports for physical activity (eg women’s walking groups, swimming clubs, yoga classes). Advise women to avoid exercising in the heat of the day and to drink plenty of water when active. Take a holistic approach: Assist women to identify ways of being physically active that are appropriate to their cultural beliefs and practices (eg activities they can do at home). 9.2.4 Resources DoHA (1999) An Active Way to Better Health. National Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/BC3101B1FF200CA4CA256F9700154958/$Fil e/adults_phys.pdf DOHA lifescript: Physical activity http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/DDEA0A1E90620C5BCA2577590006AC6E/ $File/physical.pdf NICE (2010) Dietary Interventions and Physical Activity Interventions for Weight Management Before, During and After Pregnancy. NICE public health guidance 27. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Sports Medicine Australia (undated) Exercise in Pregnancy. Sports Medicine Australia Women in Sport Fact Sheet. http://sma.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2009/10/WIS-ExPreg.pdf 9.2.5 References ACOG (2002) Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion No. 267. Obstet Gynecol 99: 171–73. AIHW (2010) Australia’s Health 2010. Australia’s health series no. 12. Cat. no. AUS 122. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. AIHW (2011) Key Indicators of Progress for Chronic Disease and Associated Determinants: Data Report. Cat. no. PHE 142. Canberra: AIHW. Barakat R, Stirling JR, Lucia A (2008) Does exercise training during pregnancy affect gestational age? A randomised controlled trial. Brit J Sports Med 42(8): 674–78. Barakat R, Ruiz JR, Lucia A (2009a) Exercise during pregnancy and risk of maternal anaemia: a randomised controlled trial. Brit J Sports Med 43(12): 954–56. Barakat R, Ruiz JR, Stirling JR et al (2009b) Type of delivery is not affected by light resistance and toning exercise training during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 201(6): 590.e1–6. CONSULTATION DRAFT Barakat R, Lucia A, Ruiz JR (2009c) Resistance exercise training during pregnancy and newborn's birth size: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Obesity 33(9): 1048–57. Barakat R, Ruiz JR, Rodriguez-Romo G et al (2010) Does exercise training during pregnancy influence fetal cardiovascular responses to an exercise stimulus? Insights from a randomised, controlled trial. Brit J Sports Med 44(10): 762–64. Barakat R, Pelaez M, Montejo R et al (2011) Exercise during pregnancy improves maternal health perception: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204(5): 402.e1–7. Bø K & Haakstad LAH (2011) Is pelvic floor muscle training effective when taught in a general fitness class in pregnancy? A randomised controlled trial. Physiother 97(3): 190–95. Boyle R, Hay-Smith EJC, Cody JD et al (2012) Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD007471. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007471.pub2. Camporesi EM (1996) Diving and pregnancy. Sem Perinatolo 20: 292–302. Cavalcante SR, Cecatti JG, Pereira RI et al (2009) Water aerobics II: Maternal body composition and perinatal outcomes after a program for low risk pregnant women. Reprod Health 6(1): 1. Ceysens G, Rouiller D, Boulvain M (2006) Exercise for diabetic pregnant women. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004225. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004225.pub2. Chuntharapat S, Petpichetchian W, Hatthakit U (2008) Yoga during pregnancy: effects on maternal comfort, labor pain and birth outcomes. Complement Ther Clin Pract 14(2): 105–15. Davies GA, Wolfe LA, Mottola MF et al (2003) Exercise in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 25(6): 516–29. DoHA (1999) An Active Way to Better Health. National Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/BC3101B1FF200CA4CA256F9700154958/$Fil e/adults_phys.pdf Haakstad LAH & BØ K (2011) Effect of regular exercise on prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 16(2): 116–25. Han S, Middleton P, Crowther CA (2012) Exercise for pregnant women for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Issue 7. Art. No.: CD009021. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009021.pub2. Hopkins SA, Baldi JC, Cutfield WS et al (2010) Exercise training in pregnancy reduces offspring size without changes in maternal insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(5): 2080–88. Kashanian M, Akbari Z, Alizadeh MH (2009) The effect of exercise on back pain and lordosis in pregnant women. Int J Gynecol Obstet 107(2): 160–61. Kramer MS & McDonald SW (2006) Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD000180. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000180.pub2. Meher S & Duley L (2006) Exercise or other physical activity for preventing pre-eclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD005942. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005942. Montoya Arizabaleta AV, Orozco Buitrago L, Aguilar de Plata AC et al (2010) Aerobic exercise during pregnancy improves health-related quality of life: a randomised trial. J Physiother 56(4): 253–58. Morkved S, Salvesen KA, Schei B et al (2007) Does group training during pregnancy prevent lumbopelvic pain? A randomized clinical trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 86(3): 276–82. Muktabhant B, Lumbiganon P, Ngamjarus C et al (2012) Interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Issue 4. Art. No.: CD007145. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007145.pub2. Nascimento SL, Surita FG, Parpinelli M et al (2011) The effect of an antenatal physical exercise programme on maternal/perinatal outcomes and quality of life in overweight and obese pregnant women: A randomised clinical trial. BJOG 118(12): 1455–63. NICE (2008) Antenatal Care. Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Press. NRHA (2011) Physical Activity in Rural Australia. Fact sheet 26. Canberra: National Rural Health Alliance. http://nrha.ruralhealth.org.au/cms/uploads/factsheets/Fact-Sheet-26-Physical-Activity.pdf Rakhshani A, Maharana S, Raghuram N et al (2010) Effects of integrated yoga on quality of life and interpersonal relationship of pregnant women. Qual Life Res 19(10): 1447–55. Ramírez-Vélez R, Aguilar de Plata AC, Escudero MM et al (2011) Influence of regular aerobic exercise on endothelium-dependent vasodilation and cardiorespiratory fitness in pregnant women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 37(11): 1601–08. RCOG (2006) Exercise in Pregnancy. Statement No. 4. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Robledo-Colonia AF, Sandoval-Restrepo N, Mosquera-Valderrama YF et al (2012) Aerobic exercise training during pregnancy reduces depressive symptoms in nulliparous women: a randomised trial. J Physiother 58(1): 9–15. Ruchat SM, Davenport M, Giroux I et al (2012) Nutrition and Exercise Reduce Excessive Weight Gain in NormalWeight Pregnant Women. Med Sci Sports Exercise 44(8): 1419–26. CONSULTATION DRAFT Satyapriya M, Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R et al (2009) Effect of integrated yoga on stress and heart rate variability in pregnant women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 104(3): 218–22. Sui Z, Grivell RM, Dodd JM (2012) Antenatal exercise to improve outcomes in overweight or obese women: A systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 91(5): 538–45. Thangaratinam S, Rogozinska E, Jolly K et al (2012) Effects of interventions in pregnancy on maternal weight and obstetric outcomes: meta-analysis of randomised evidence. BMJ 344 e2088. Vinter CA, Jensen DM, Ovesen P et al (2011) The LiP (Lifestyle in Pregnancy) study: a randomized controlled trial of lifestyle intervention in 360 obese pregnant women. Diab Care 34(12): 2502–07.