File

advertisement

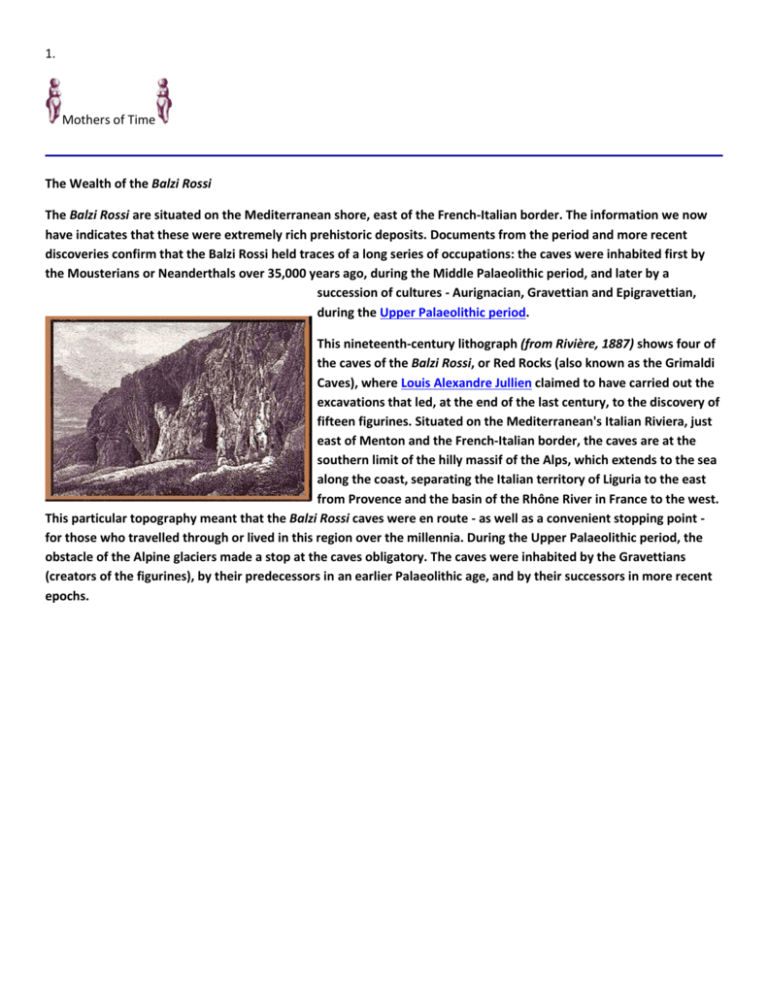

1. Mothers of Time The Wealth of the Balzi Rossi The Balzi Rossi are situated on the Mediterranean shore, east of the French-Italian border. The information we now have indicates that these were extremely rich prehistoric deposits. Documents from the period and more recent discoveries confirm that the Balzi Rossi held traces of a long series of occupations: the caves were inhabited first by the Mousterians or Neanderthals over 35,000 years ago, during the Middle Palaeolithic period, and later by a succession of cultures - Aurignacian, Gravettian and Epigravettian, during the Upper Palaeolithic period. This nineteenth-century lithograph (from Rivière, 1887) shows four of the caves of the Balzi Rossi, or Red Rocks (also known as the Grimaldi Caves), where Louis Alexandre Jullien claimed to have carried out the excavations that led, at the end of the last century, to the discovery of fifteen figurines. Situated on the Mediterranean's Italian Riviera, just east of Menton and the French-Italian border, the caves are at the southern limit of the hilly massif of the Alps, which extends to the sea along the coast, separating the Italian territory of Liguria to the east from Provence and the basin of the Rhône River in France to the west. This particular topography meant that the Balzi Rossi caves were en route - as well as a convenient stopping point for those who travelled through or lived in this region over the millennia. During the Upper Palaeolithic period, the obstacle of the Alpine glaciers made a stop at the caves obligatory. The caves were inhabited by the Gravettians (creators of the figurines), by their predecessors in an earlier Palaeolithic age, and by their successors in more recent epochs. 2. Mary Leakey: Unearthing History Editors' Note: Mary Leakey, one of the world's most renowned hunters of early human fossils, died in Nairobi on December 9, 1996, at the age of 83. Crowning triumphs of her long career included such finds as the 1972 discovery (with Louis, her husband and collaborator) of 1.75-million-year-old remains from Homo habilis at Olduvai Gorge and the 1978 discovery of 3.6million-year-old footprints at Laetoli, both in Tanzania. This profile of Dr. Leakey, written by former news editor Marguerite Holloway, originally appeared in the October 1994 issue of Scientific American By Marguerite Holloway | December 16, 1996 Mary Leakey waits for my next question, watching from behind a thin curtain of cigar smoke. Leakey is as famous for her precision, her love of strong tobacco--half coronas, preferably Dutch--and her short answers as she is for some of the most significant archaeological and anthropological finds of this century. The latter would have hardly been excavated without her exactitude and toughness. And in a profession scarred by battles of interpretation and of ego, Leakey's unwillingness to speculate about theories of human evolution is unique. These characteristics have given Leakey a formidable reputation among journalists and some of her colleagues. So have her pets. In her autobiography, Disclosing the Past, Leakey mentions a favorite dog who tended to chomp people whom the archaeologist didn't like, "even if I have given no outward sign." So as we talk in her home outside Nairobi, I sit on the edge of a faded sofa, smiling exuberantly at her two dalmatians, Jenny and Sam, waiting for one of them to bite me. I quickly note details--her father's paintings on the wall, the array of silver trophies from dog shows and a lampshade with cave painting figures on it--in case I have to leave suddenly. But the two dogs and soon a cat and later a puppy sleep or play, and Leakey's answers, while consistently private, seem less terse than simply thoughtful. Leakey first came to Kenya and Tanzania in 1935 with her husband, the paleontologist Louis Leakey, and except for forays to Europe and the U.S., she has been there ever since. During those many years, she introduced modern archaeological techniques to African fieldwork, using them to unearth stone tools and fossil remains of early humans that have recast the way we view our origins. Her discoveries made the early ape Proconsul, Olduvai Gorge, the skull of Zinjanthropus and the footprints of Laetoli, if not household names, at least terms familiar to many. Leakey was born in England, raised in large part in France and appears to have been independent, exacting and abhorrent of tradition from her very beginnings. Her father, an artist, took his daughter to see the beautiful cave paintings at such sites as Fond de Gaume and La Mouthe and to view some of the stone and bone tools being studied by French prehistorians. As she has written, these works of art predisposed Leakey toward digging, drawing and early history: "For me it was the sheer instinctive joy of collecting, or indeed one could say treasure hunting: it seemed that this whole area abounded in obje cts of beauty and great intrinsic interest that could be taken from the ground." These leanings ultimately induced Leakey at the age of about 17 to begin working on archaeological expeditions in the U.K. She also attended lectures on archaeology, prehistory and geology at the London Museum and at University College London. Leakey says she never had the patience for formal education and never attended university; she never attended her governesses either. (At the same time, she is delighted with her many honorary degrees: "Well, I have worked for them by digging in the sun.") A dinner party following a lecture one evening led her, in turn, to Louis Leakey. In 1934 the renowned researcher asked Mary, already recognized for her artistic talents, to do the illustrations for a book. The two were soon off to East Africa. They made an extraordinary team. "The thing about my mother is that she is very low profile and very hard working," notes Richard E. Leakey, former director of the Kenya Wildlife Service, an iconoclast known for his efforts to ban ivory trading and a distinguished paleontologist. "Her commitment to detail and perfection made my father's career. He would not have been famous without her. She was much more organized and structured and much more of a technician. He was much more excitable, a magician." What the master and the magician found in their years of brushing away the past did not come easily. From 1935 until 1959 the two worked at various sites throughout Kenya and Tanzania, searching for the elusive remains of early humans. They encountered all kinds of obstacles, including harsh conditions in the bush and sparse funding. Success too was sparse--until 1948. In that year Mary found the first perfectly preserved skull and facial bones of a hominoid, Proconsul, which was about 16 million years old. This tiny Miocene ape, found on Rusinga Island in Lake Victoria, provided anthropologists with their first cranium from what was thought to be the missing link--a tree-dwelling monkey boasting a bigger brain than its contemporaries. Proconsul was a stupendous find, but it did not improve the flow of funds. The Leakeys remained short of financial support until 1959. The big break came one morning in Olduvai Gorge, an area of Tanzania near the Great Rift Valley that slices East Africa from north to south. Again it was Mary who made the discovery. Louis was sick, and Mary went out to hunt around. Protruding slightly from one of the exposed sections was a roughly 1.8-million-year-old hominid skull, soon dubbed Zinjanthropus. Zinj became the first of a new group--Australopithecus boisei-and the first such skull to be found in East Africa. Australopithecus boisei "For some reason, that skull caught the imagination," Leakey recalls, pausing now and then to relight her slowly savored cigar or to chastise a dalmatian for being too forward. "But what it also did, and that was very important for our point of view, it caught the imagination of the National Geographic Society, and as a result they funded us for years. That was exciting." How Zinj fits into the family tree is not something Leakey will speculate about. "I never felt interpretation was my job. What I came to do was to dig things up and take them out as well as I could," she describes. "There is so much we do not know, and the more we do know, the more we realize that early interpretations were completely wrong. It is good mental exercise, but people get so hot and nasty about it, which I think is ridiculous." I try to press her on another bone of contention: Did we Homo sapiens emerge in Africa, or did we spring up all over the world from different ancestors, a theory referred to as the multiregional hypothesis? Leakey starts to laugh. "You'll get no fun out of me over these things. If I were Richard, I would talk to you for hours about it, but I just don't think it is worth it." She pauses. "I really like to feel that I am on solid ground, and that is never solid ground." In the field, Leakey was clearly on terra firma. Her sites were carefully plotted and dated, and their stratigraphy--that is, the geologic levels needed to establish the age of finds--was rigorously maintained. In addition to the hominid remains found and catalogued at Olduvai, Leakey discovered tools as old as two million years: Oldowan stone tools. She also recorded how the artifacts changed over time, establishing a second form, Developed Oldowan, that was Oldowan Tools in use until some 500,000 years ago. "The archaeological world should be grateful that she was in charge at Olduvai," notes Rick Potts, a physical anthropologist from the Smithsonian Institution who is studying Olorgesailie, a site about an hour south of Nairobi where the Leakeys found ancient stone axes in 1942. Now, as they did then, the tools litter the white, sandy Maasai savanna. The most beautiful ones have been stolen, and one of Leakey's current joys is that the Smithsonian is restoring the site and its small museum and plans to preserve the area. Olduvai Gorge has not fared as well. After years of residence and work there, and after the death of Louis in 1972, Mary finally retired in 1984. Since then, she has worked to finish a final volume on the Olduvai discoveries and has also written a book on the rock paintings of Tanzania. "I got too old to live in the bush," she explains. "You really need to be youngish and healthy, so it seemed stupid to keep going." Once she left, however, the site was ignored. "I go once a year to the Serengeti to see the wildebeest migrations because that means a lot to me, but I avoid Olduvai if I can because it is a ruin. It is most depressing." In outraged voice, she snaps out a litany of losses: the abandoned site, the ruined museum, the stolen artifacts, the lost catalogues. "Fortunately, there is so much underground still. It is a vast place, and there is plenty more under the surface for future generations that are better educated." Leakey's most dramatic discovery, made in 1978, and the one that she considers most important, has also been all but destroyed since she left the field. The footprints of Laetoli, an area near Olduvai, gave the world the first positive evidence of bipedalism. Three hominids (generally identified as Australopithecus afarensis ) had walked over volcanic ash, which fossilized, preserving their tracks. The terrain was found to be about 3.6 million years old. Although there had been suggestions in the leg bones of other hominid fossils, the footprints made the age of bipedalism incontrovertible. "It was not as exciting as some of the other discoveries, because we did not know what we had," she notes. "Of course, when we realized what they were, then it was really exciting." Today the famous footprints may only be salvaged with the intervention of the Getty Conservation Institute. "Oh, they are in a terrible state," Leakey exclaims. "When I left, I covered them over with a mound of river sand and then some plastic sheeting and then more sand and a lot of boulders on top to keep the animals off and the Maasai off." But acacia trees took root and grew down among the tracks and broke them up. Although Leakey steers clear of controversy in her answers and her writings, she has not entirely escaped it. She and Donald Johanson, a paleontologis t at the Institute of Human Origins in Berkeley, Calif., have feuded about the relation between early humans found in Ethiopia and in Laetoli. (Johanson set up his organization as a philosophical counterweight to the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.) And some debate erupted about how many prints there were at Laetoli. Tim White of the University of California at Berkeley claimed that there were only two and that Leakey and her crew had made the other track with a tool during excavation. Leakey's response? "It was a nonsense," she laughs, and we are on to the next subject. A subject Leakey does not like. "'What was it like to be a woman? A mother? A wife?' I mean that is all such nonsense," she declares. Leakey--like many other female scientists of her generation, including Nobel laureates Rita Levi-Montalcini and Gertrude Belle Elion--dislikes questions about being a woman in a man's field. Her sex played no role in her work, she asserts. She just did what she wanted to do. "I was never conscious of it. I am not lying for the sake of anything. I never felt disadvantaged." Leakey just did her work, surviving bitter professional wars in anthropolog y and political upheavals. In 1952 Louis, who had been made a member of the Kikuyu tribe during his childhood in Africa, was marked for death during the Mau Mau uprising. The four years during the height of the rebellion were terrifying for the country. The brakes on Mary's car were tampered with, and a relative of Louis's was murdered. The house that Leakey lives in today was designed during this time: a low, white square structure with a central courtyard where the dogs can run at night. These pets are very important to Leakey--a source of companionship and safety out in the bush. She admires the traits in them that others admire in her: independence and initiative. (Any small joy that I have about emerging from her house unbitten fades sadly when I reread the section in her autobiography about her telepathic dalmatian and learn that he died years ago.) We seem to have covered everything, and so she reviews her discoveries aloud. "But you have not mentioned the fruits," she reminds me. One of Leakey's favorite finds is an assortment of Miocene fossils: intact fruits, seeds, insects-- including one entire ant nest--and a lizard with its tongue hanging out. They lay all over the sandy ground of Rusinga Island. "We only found them because we sat down to smoke a cigarette, hot and tired, and just saw all these fruits lying on the ground next to us. Before that we had been walking all over them all over the place." She stops. "You know, you only find what you are looking for, really, if the truth be known." 3. Discovering our human origins Donald C. Johanson was born in Chicago, Illinois. Although his parents were Swedish immigrants with little education, his father, a barber, supported the family in relative comfort. All that changed when Johanson was two. His father died, leaving the family without any means of support. Johanson's mother worked as a cleaning lady to support them in far more modest circumstances, but always encouraged Johanson to study and prepare himself for a rewarding career. Although Johanson did poorly on the Standardized Aptitude Test, an anthropologist neighbor encouraged him in his ambitions to become a scientist, and he was accepted to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He was determined to become an anthropologist and specialize in the study of human origins. Since one of the leading scholars in the field, Clark Howell, was at the university of Chicago, Johanson wrote to him and arranged a meeting. With Howell's support, Johanson transferred to the University of Chicago, where he won his bachelor's degree in 1966. He went on to earn his Master's and Ph.D. at the same institution. As a Professor of Anthropology, his career took him from Case Western University, to Kent State, to Stanford, but his reputation is based on his archaeological work in the field, which began while he was still an undergraduate. His first trip to Africa came in 1970; he has participated in expeditions in South Africa, Tanzania and, most famously, Ethiopia. It was at the Hadar site, in the Afar region of Ethiopia the Johanson made the discovery that changed our understanding of human origins forever. There, in 1974, he found the fossilized remains of a female hominid the world came to know as Lucy. Until then, paleoanthropologists had had to content themselves with the most fragmentary remnants of our pre-human ancestors. Over 40 percent of the Lucy skeleton had been preserved, enough to provide the anthropological world with some startling insights. The previously accepted account of human evolution had proposed that a strain of primates with larger brains evolved, became capable of making tools, and began walking upright to free up their hands. But, from all appearances, Lucy and the other hominids whose remains were found at the site, were walking upright, although their brains were barely larger than those of the chimpanzee. No stone tools, not even fragments, have survived at the stratum where Lucy and her contemporaries were found. From this, it may be inferred that our ancestors walked upright for another reason. They may have used their hands to carry food gathered for their offspring, and engaged in more elaborate cooperative behavior than one finds among creatures who walk on all fours. At first, many scholars believed these remains were specimens of a previously identified species,Australopithecus africanus, but after years of studying the staggering assortment of fossils found at the Hadar site, Johanson came to another conclusion. In 1978, he shocked the scientific community with an assertion that the remains belonged to another distinct species, which he named Australopithecus afarensis. Throughout the 1980s, the turbulent political situation in Ethiopia barred Johanson and his colleagues from returning to the site. In 1990, the fossil hunters were allowed to return and by 1992 had found a large portion of an afarensis skull. The reconstruction of the head silenced most of Johanson's critics and afarensis is now widely recognized as the ancestor of both Australopithecus africanus and modern man, Homo sapiens.Books Johanson has co-authored include:Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind, Blueprints: Solving the Mystery of Evolution, Lucy's Child: The Discovery of a Human Ancestor, Journey From the Dawn: Life With the World's First Family, Ancestors: In Search of Human Origins, and From Lucy to Language. Since 1980, Johanson has participated in the production of more than one documentary series for Public Television. He appeared as the on-screen host of a 13-part series for Nature in 1982, and for theNova series in 1994. Today, Donald Johanson is Director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona. 4. African Skull Suggests Diversity of Early Human Relatives By JOHN NOBLE WILFORD Published: October 7, 1997 A TEAM of Japanese, American and Ethiopian paleontologists, embodying the diversity among modern humans, has found a 1.4-million-year-old skull in Africa and a new reason to think that individuals within fossil species of early human relatives were also manifestly diverse. The discovery, reported in the current issue of the journal Nature, offers a cautionary tale for all scientists interpreting fossil finds: beware of splitting fossils into different species on the basis of minor variations in a limited sampling of individual specimens. The discovery team said the skull belonged to the species Australopithecus boisei, a robust member of the now-extinct branch of the human family tree that split off more than 2.5 million years ago from the lineage that led to living people. The boisei species was first identified almost 40 years ago, but this is the largest known skull, the first one found with an intact lower jaw and the first to be excavated in Ethiopia. From previous finds, the species appeared to be concentrated in Kenya and Tanzania. In most of its characteristics, the paleontologists said, the skull is typical of a large A. boisei male. But they noted a few differences. The cheekbones look more like those of a southern African species called A. robustus. The back of the cranium resembles another species, A. aethiopicus. And the short, broad palate is shaped like one from the genus Homo, the family branch that includes modern humans. The unexpected combination of cranial and facial features of this skull, the discoverers said, probably represented geographical variations within the species and did not justify declaring this to be a new fossil species. Other research indicated that these northern members of the species seemed to have adapted to a predominantly dry grassland environment, compared with the relatively moist and wooded habitats favored by the species elsewhere in Africa. The skull was excavated at Konso, Ethiopia, by a team led by Gen Suwa of the University of Tokyo and including Dr. Berhane Asfaw of the Rift Valley Research Service in Ethiopia and Dr. Tim D. White of the University of California at Berkeley. Although A. boisei was not a direct ancestor of modern humans, Homo sapiens sapiens, it was one of several australopithecine species that shared a common ancestor with the Homo genus, and evolved in parallel after 3 million to 2.5 million years ago. Boisei lived from around 2.3 million years to about 1.4 million years ago, meaning the skull is from the most recent known member of the species. The entire australopithecine branch became extinct about one million years ago. The discoverers' interpretation of the skull as a geographical variant of A. boisei, not an entirely different species, is certain to rekindle debate between the ''lumpers'' and the ''splitters'' of paleoanthropology. Lumpers tend to be inclusive, assigning fossils that are similar to a single species, even though they exhibit some variations. Splitters are more exclusive, suggesting that any discernible difference in morphology implies that interbreeding would have been unlikely. The inability to interbreed is a primary way of separating living animals into distinct species. Such a test, of course, cannot be directly applied to fossils. Concluding their report, the discoverers wrote, ''We predict that, as new hominid-bearing sedimentary basins are discovered and existing site samples are augmented, a more accurate picture of variation will emerge to challenge overly split phylogenies of hominid species.'' Dr. Eric Delson, a paleoanthropologist at the City University of New York and the American Museum of Natural History, agreed with the lumper interpretation for the Konso skull, writing in a separate journal article that ''the greatest importance of this specimen is its implication for the study of variation in this, and other, human populations and species.'' In an interview, Dr. Delson said: ''We certainly know that people from different parts of the world today look different, and yet are all Homo sapiens. But all too often, paleontologists jump on small variations in appearance and say this must represent a different species.'' Photo: The ambiguous skull from Konso. (Courtesy of Nature) Map: ''A Question of Identity'' All these sites have yielded fossils identified as Australopithecus boiseii; sites marked with white boxes have also yielded Australopithecus ethiopicus; the newly found skull from Konso resembles those of both species and has characteristics of still a third, Australopithecus rubustus. Map shows the location of Konso, Ethiopia. 5. Ardipithecus ramidis, a new species of early hominid from Ethiopia In September, 1994, in Nature, Tim D. White and two students named Australopithecus ramidus, a new species of early hominid. In a corrigendum in 1995 they placed the species in a new genus,Ardipithecus. 'Ardi' means ground or floor in the Afar language. The species was based on seventeen hominoid fossils with dental, cranial and postcranial specimens, all from Aramis, Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Both the antiquity, around 4.4 mya, and the primitive morphology suggest an ancestral species for the Hominidae. Prior to this publication the earliest hominid species wasAustralopithecus afarensis, dated to between 3.0 and 3.6 (possibly 3.8) mya. A. ramidis was named in recognition of the Afar people who contributed to fieldwork. 'Ramid' means 'root' in the Afar language. The type, ARA-VP-6/1, an associated set of teeth from one individual, was found by Gada Hamed in December of 1993. The specimens were collected in 1992 and 1993. The hominid specimens were surface finds with the immediately underlying tuff dated at 4.39 mya. The authors distinguished the species as follows: "upper and lower canines larger relative to the postcanine teeth; lower first deciduous molar narrow and obliquely elongate, with large protoconid, small and distally placed metaconid, no anterior fovea, and small, low talonid with minimal cuspule development; temporomandibular joint without definable articular eminence; absolutely and relatively thinner canine and molar enamel; lower third premolar more strongly asymmetrical, with dominant, tall buccal cusp and steep, posterolingually directed transverse crest; upper third premolar more strongly asymmetric, with relatively larger, taller, more dominant buccal cusp. "A. ramidus is distinguished as a hominid ... by the following: canine morphology more incisiform, crowns less projecting, with relatively higher crown shoulders, cupped distal wear pattern on lower canine; mandibular P3 with weaker mesiobuccal projection of the crown base and without functional honing facet, modally relatively smaller mandibular P3; modally relatively broader lower molars, foramen magnum anteriorly placed relative to carotid foramen; hypoglossal canal anteriorly placed relative to internal auditory meatus; carotid foramen placed posteromedial to tympanic angle." The dental description benefits from the ARA-VP-1/129 child's mandible retaining a first deciduous molar. The deciduous molar has been used for sorting apes and hominids. The Aramis deciduous molar is far closer to a chimpanzee's than to previously described hominids. The cranial fossils were described as evincing "a strikingly chimpanzee-like morphology." The anterior foramen magnum distinguishes A. ramidis and infers bipedality. This feature, together with a more incisiform canine with reduced sexual dimorphism places this species clearly among the hominids. The postcranial characteristics are a mosaic of hominid and great ape characteristics. Australopithecus was first described by Raymond Dart, after a student brought him a fossil from a quarry. Dart contacted the quarry manager, who sent him two crates of fossiliferous breccias. Dart noticed a natural endocast and found the crania, a juvenile known as the Taung child. This first Australopithecine, the type for the genus, represents the first monumental discovery of an early hominid. The Taung Child fossil, Australopithecus africanus Click on images for a larger views. Photo courtesy IHO/Kimbel. Sources: White, Tim D., Gen Suwa and Berhabe Asfaw. 1994. Australopithicus ramidis, a new species of early hominid from Aramis, Ethiopia. Nature 371:306-312. White, Tim D., Gen Suwa and Berhabe Asfaw. 1995. Corrigendum. Australopithicus ramidis, a new species of early hominid from Aramis, Ethiopia. Nature 375:88. 6. History of the excavations at Catal Huyuk The Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük was first discovered in the late 1950s and excavated by James Mellaart in 4 excavation seasons between 1961 and 1965. The site rapidly became famous internationally due to the large size and dense occupation of the settlement, as well as the spectacular wall paintings and other art that was uncovered inside the houses. The results of these excavations as published can be found on the reading list. Plan of James Mellaart's excavations showing the dense house lauyout. Wall paintings discovered in the 1960s As well as wall paintings and wall reliefs, many objects of daily life were uncovered. Some were decorative such as exceptional flint 'daggers' with decorative bone handles (right) and clay or stone figurines (left), depicting human figures and animals. Other utilitarian objects include obsidian, flint, pottery, worked bone and clay balls. Another distinguishing feature of Çatalhöyük was the nature of the houses: they had no doors to the outside and were clearly entered through ladders from the roof, and the inhabitants buried their dead under the floors of their platforms. Since 1993 an international team of archaeologists, led by Professor Ian Hodder, has been carrying out new research at Çatalhöyük. After the first seasons of surface survey, the excavations in the North and South Areas began in 1995 and have continued up to the present day. During the first phase of excavation to 1999 teams based in Cambridge, Berkeley and Thessaloniki joined Turkish colleagues to excavate individual buildings. The primary aim was to study the depositional processes in houses. For example, Buildings 1 and 5 were excavated on the North part of the site, and Building 5 has now been put on display. The Berkeley team excavated the BACH Building 3 also in the North Area. Since 1999 work has focused on publication, and on a new and more expansive approach to the excavations so that the overall organization of the site can be studied. The team is now based in Stanford, Berkeley and London, and we have been joined by teams from Poznan University in Poland, and from Istanbul and Selcuk Universities. The main excavation areas are the TP and South and Istanbul areas in the south part of the mound, and the 4040 Area in the north. Throughout, there has been excavation also on the Clacolithic West Mound, and to the north of the East Mound in the KOPAL Area. All this work is documented on this web site in Newsletters and detailed Archive Reports. Finds from the recent excavations Clay figurine Obsidian point Bone hook Neolithic pot beads 7. http://www.lascaux.culture.fr/#/en/02_00.xml On September 12, 1940, the entrance to Lascaux Cave was discovered by 18-year-old Marcel Ravidat. Ravidat returned to the scene with three friends, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas, and entered the cave via a long shaft. The teenagers discovered that the cave walls were covered with depictions of animals.[5][6] The cave complex was opened to the public in 1948.[7] By 1955, the carbon dioxide, heat, humidity, and other contaminants produced by 1,200 visitors per day had visibly damaged the paintings and introduced lichen on the walls. The cave was closed to the public in 1963 to preserve the art. After the cave was closed, the paintings were restored to their original state and were monitored daily. Rooms in the cave include the Hall of the Bulls, the Passageway, the Shaft, the Nave, the Apse, and the Chamber of Felines. Lascaux II, a replica of the Great Hall of the Bulls and the Painted Gallery located 200 meters away from the original, was opened in 1983, so that visitors may view the painted scenes without harming the originals.[6]Reproductions of other Lascaux artwork can be seen at the Centre of Prehistoric Art. The cave contains nearly 2,000 figures, which can be grouped into three main categories: animals, human figures, and abstract signs. The paintings contain no images of the surrounding landscape or the vegetation of the time.[10] Most of the major images have been painted onto the walls using mineral pigments, although some designs have also been incised into the stone. Many images are too faint to discern, and others have deteriorated entirely. Over 900 can be identified as animals, and 605 of these have been precisely identified. Out of these images, there are 364 paintings of equines as well as 90 paintings of stags. Also represented are cattle and bison, each representing 4 to 5% of the images. A smattering of other images include seven felines, a bird, a bear, a rhinoceros, and a human. There are no images of reindeer, even though that was the principal source of food for the artists.[11] Geometric images have also been found on the walls. The most famous section of the cave is The Great Hall of the Bulls where bulls, equines, and stags are depicted. The four black bulls, or aurochs, are the dominant figures among the 36 animals represented here. One of the bulls is 5.2 metres (17 ft) long, the largest animal discovered so far in cave art. Additionally, the bulls appear to be in motion.[11] In recent years, new research has suggested that the Lascaux paintings may incorporate prehistoric star charts. Michael Rappenglueck of the University of Munich argues that some of the non-figurative dot clusters and dots within some of the figurative images correlate with the constellations of Taurus, thePleiades and the grouping known as the "Summer Triangle".[12] Based on her own study of the astronomical significance of Bronze Age petroglyphs in theVallée des Merveilles[13] and her extensive survey of other prehistoric cave painting sites in the region—most of which appear to have been selected because the interiors are illuminated by the setting sun on the day of the winter solstice—French researcher Chantal Jègues-Wolkiewiez has further proposed that the gallery of figurative images in the Great Hall represents an extensive star map and that key points on major figures in the group correspond to stars in the main constellations as they appeared in the Paleolithic.[14][15] An alternative hypothesis proposed by David Lewis-Williams and Jean Clottesfollowing work with similar art of the San people of Southern Africa is that this type of art is spiritual in nature relating to visions experienced during ritualistictrance-dancing. These trance visions are a function of the human brain and so are independent of geographical location. Nigel Spivey, a professor of classic art and archeology at the University of Cambridge, has further postulated in his series, How Art Made the World, that dot and lattice patterns overlapping the representational images of animals are very similar to hallucinations provoked by sensory-deprivation. He further postulates that the connections between culturally important animals and these hallucinations led to the invention of image-making, or the art of drawing. Further extrapolations include the later transference of image-making behavior from the cave to megalithic sites, and the subsequent invention of agriculture to feed the site builders. Some anthropologists and art historians also theorize that the paintings could be an account of past hunting success, or could represent a mystical ritual in order to improve future hunting endeavors. This latter theory is supported by the overlapping images of one group of animals in the same cave-location as another group of animals, suggesting that one area of the cave was more successful for predicting a plentiful hunting excursion. Applying the iconographic method of analysis to the Lascaux paintings (studying position, direction and size of the figures; organization of the composition; painting technique; distribution of the color planes; research of the image center), Thérèse Guiot-Houdart attempted to comprehend the symbolic function of the animals, to identify the theme of each image and finally to reconstitute the canvas of the myth illustrated on the rock walls.[16][further explanation needed] The Lascaux paintings' disposition may be explained by a belief in the real life of the pictured species, wherein the artists tried to respect their real environmental conditions.[19]