Title: Preventing HIV in Vietnam – 1-year extension

advertisement

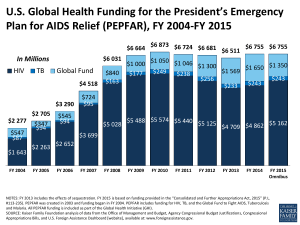

Business Case and Intervention Summary Intervention Summary Title: Preventing HIV in Vietnam – 1-year extension What support will the UK provide? The UK will make available an additional grant of £6.2 million from January 2013 to December 2013 to ensure a well-managed transition to the Global Fund financed programme and to the domestically financed HIV National Targeted Programme. This will help the Government of Vietnam to sustain its current achievements in HIV prevention and ensure sustainability of the initiatives supported over the past decade by the DFID and World Bank funded HIV/AIDS prevention programmes. This will increase DFID’s total contribution to the programme to £24.2 million. The additional grant by DFID will finance: Harm reduction for people who inject drugs, including needle/syringe programmes and methadone maintenance therapy (for 9 months only) – £1,240,000 Condom social marketing – £2,052,000 Work among men who have sex with men – £437,000 Strengthening the national monitoring and evaluation system for HIV and AIDS – £282,000 Training and advocacy – £1,142,000 Programme management – £797,000 DFID-managed international consultancy support – £250,000 Why is UK support required? DFID and the World Bank have been the main financiers of harm reduction programmes among the highest risk groups in Vietnam. This work has been highly effective, Vietnam now seeing annual incidence of new HIV infections in decline for the last four consecutive years, with prevalence among people who inject drugs (until now the primary drivers of the epidemic) having come down from 29% to 13% during the time that DFID has been supporting prevention programmes. The current joint DFID/WB project was scheduled to close in December 2012, with crucial HIV prevention activities being handed over to programmes funded by other donors (mainly the Global Fund) and by domestic resources (the National Targeted Programme for HIV). However, Vietnam is facing an unprecedented and unexpectedly rapid loss of donor resources. The Global Fund cancelled Round 11, on which Vietnam had placed high hopes, and has notified Vietnam that if the Phase 2 of round 9 is granted there will inevitably be a funding gap for the first months of 2013. At the same time the US Government’s PEPFAR programme is reducing its financial commitments to Vietnam much faster than originally planned. Furthermore, Vietnam’s National Assembly cut financing to the National Targeted Programme by 50% due to Vietnam’s own domestic economic problems. These unforeseen funding problems mean that if the DFID/WB support ends in 2012, some crucial prevention activities will be interrupted in the first half of 2013, severely jeopardizing the progress that has been made to date and potentially losing much of the legacy that DFID wishes to leave in Vietnam. This project extension will provide bridging funding for some essential activities pending additional resources expected from the Global Fund from mid-2013 and will also allow time for more sustainable 1 models to be developed for some important activities. This will involve more work through the private sector to ensure universal availability of condoms and needles/syringes. Further work on strengthening the evidence base and on advocacy with national and provincial policy makers will be aimed at making increased and better targeted domestic resources available. What are the expected results? The project will ensure that HIV continues to be controlled in Vietnam, focusing on the most-at-risk populations, as is appropriate for a concentrated epidemic. Prevalence among people who inject drugs and female sex workers should continue to decline and the rising prevalence among men who have sex with men should be halted. Specific targets are to keep the prevalence rate among adults aged 1549 at below 0.45%; the prevalence rate among people who inject drugs below 13%; the prevalence rate among female sex workers below 3%; and the prevalence rate among men have sex with men below 17%. It is not possible to measure prevalence rates accurately every year, but estimates will be updated through surveys conducted every 2-3 years. Trends in prevalence rates can be roughly estimated annually from sentinel surveillance data. The project aims to scale up and institutionalize best-practice models of HIV and AIDS control which can then be sustained in the longer term by the Vietnamese Government. A significant proportion of project resources is allocated to training and advocacy, all of which is aimed at improving sustainability. Annual performance of the project is measured in terms of maintaining low levels of high-risk behaviours. Specific targets for the extension period are: (1) consistent use of clean needles by people who inject drugs maintained at over 80% in the 32 participating provinces; (2) consistent use of condoms by female sex workers maintained at over 90% in the 32 participating provinces; (3) consistent use of condoms by men who have sex with men brought up to over 60% in the 10 provinces targeted for this work; (4) 2,200 patients are retained on methadone maintenance therapy. In order to help achieve these results the project will provide in 2013 22 million needles/syringes and over 42 million condoms. The original targets for the existing project were 80% condom use by female sex workers (baseline 60%) and 70% clean needle use by people who inject drugs (baseline 50%). As at mid-2012 both of these targets have been significantly over-achieved. There was no target set for condom use by men who have sex with men, but the limited survey data available suggest rates varying between 15% and 59% depending on location and type of partner. There are currently about 1700 patients retained on methadone maintenance therapy in DFID/WBsupported clinics, which is less than originally planned. However, the number is constrained by the availability of methadone, currently procured by USAID. USAID has budgeted for 40 methadone clinics, which include 6 supported by the DFID/WB project. 2 Business Case Strategic Case A. Context and need for a DFID intervention Epidemiological context HIV was first recognized in Viet Nam in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) in 1990, and spread rapidly across the country. As of 31 December 2011, HIV cases had been reported in all 63 provinces, 98% of districts and 77% of communes. The cumulative total since records began was 249,660 reported HIV cases, with 197,335 PLHIV still living and 52,325 AIDS-related deaths. In 2011 Vietnam had the fourth highest number of people living with HIV in Asia (after India, China and Thailand). The epidemic in Viet Nam comprises many sub-epidemics across the country and remains concentrated primarily among three populations defined by high levels of HIV-transmission risk behaviours: people who inject drugs (PWID) (predominantly men), men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers (FSW). According to 2011 sentinel surveillance, HIV prevalence among PWID had dropped to 13.4%, down from 29% in 2001-2002. Prevalence among FSW was 3%, down from 6% in 2002. IBBS data indicates that prevalence among MSM was 16.7% in 2009 and rising, although only four major cities were surveyed. Injecting drug use has been the primary route of HIV transmission until now, but a rise in reported cases of HIV-positive women, who now represent 31% of newly reported cases, reflects a probably slow but steady transmission of HIV to women by men engaging in highly risky behaviours, mainly PWID and MSM. However, the scale-up of prevention of mother-to child transmission services and a high HIV-testing coverage of pregnant women mean that it is likely that some proportion of these newly reported cases comes from increased testing rather than increased transmission. Overall the estimate of adult HIV prevalence (ages 15-49) remained at 0.45% in 2011, unchanged from 2010. This is one of the highest prevalence rates in Asia. At two sentinel sites, in Dien Bien province in the north-western hills and in Hanoi city, prevalence among pregnant women exceeded 1% in 2011. Political, institutional and social context Overall leadership and coordination of Vietnam’s response to HIV and AIDS is provided by the National Committee for AIDS, Drugs and Prostitution Prevention and Control, chaired by a Deputy Prime Minister. The current Deputy Prime Minister is steering a progressive path, gradually dismantling the old “social evils” agenda (which focused on removing drug users and sex workers from society by locking them up in detention centres for forced rehabilitation) and promoting more modern (and proven effective) methods. The new law no longer requires sex workers to be detained, but provides for their voluntary rehabilitation. There is a moratorium on the construction of detention centres for drug users and the numbers in compulsory detention have dropped rapidly over the past two years. The Government is now promoting the rapid scale-up of methadone maintenance therapy and community-based treatment and rehabilitation of drug users. Nevertheless, there are still conservative elements in the Public Security and Social Affairs departments, both of which play key roles in controlling drug use and sex work. Furthermore, conservative elements in the National Assembly and in other parts of Government are very influential in restricting the amount of funding that is available for effective HIV control, with the preference generally being for a traditional punitive approach. There is also a lot of variation between provinces, with some cities like Hai Phong and Can Tho leading the way with progressive approaches and others like Ho Chi Minh and Da Nang taking much more conservative and traditional approaches. The project, working together with the 3 UN agencies and US Government agencies, continues to advocate for more effective approaches and a greater level of domestic resource allocation, and a key activity of the proposed extension will be to build the evidence base still further, demonstrating the effectiveness of a comprehensive harm reduction programme not only in reducing HIV transmission but also in controlling crime. Of the three high-risk behaviours (commercial sex, injecting drug use and anal sex between men), sex work by FSW is the least stigmatized in Vietnamese society. Despite there being no law against sex between consenting adult men, all kinds of homosexual behaviour are highly stigmatized in Vietnam. Until very recently the majority of Provincial AIDS Centres were in denial about the existence of gay communities in their provinces. The hidden nature of MSM communities makes the sub-epidemic among them much more dangerous. It is estimated that 3% of Vietnam’s population belongs to the lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender (LGBT) community, making it by far the largest highrisk population for HIV transmission. However, due to the emergence of compelling evidence coupled with advocacy by internationally-funded projects, including this one, almost all provinces are now factoring work among MSM into their annual action plans. With the exception of a few cities that have developed more sophisticated approaches, most provinces are still learning how to engage with MSM communities. Given the high rates of HIV prevalence recorded among MSM, developing effective ways of working among MSM needs to be a high priority in Vietnam’s HIV prevention strategy. The day-to-day work of combatting the HIV epidemic in Vietnam is managed centrally by the Vietnam Administration of HIV and AIDS Control (VAAC), a department that reports to the Ministry of Health. At the provincial level, where most programme implementation takes place, the Provincial AIDS Centres (PACs) manage the response. These report to the Provincial People’s Committees and ensure coordination between key departments, especially Health, Public Security and Social Affairs. All donor-funded projects are implemented under the overall control of VAAC and the PACs, although many of the US Government funded activities are implemented by international agencies. The DFID/WB funded work is implemented solely by the Government, with technical support provided by WHO. Complete social, institutional and political appraisals were conducted during the original project design and are included in the Project Memorandum. These are still valid and relevant. HIV prevention work in Vietnam DFID and the World Bank have been the main financiers of HIV prevention programmes among the highest risk groups in Vietnam. DFID started funding the £17 million “Preventing HIV in Vietnam Project” in 2003 with the purpose of reducing vulnerability to HIV infection in Vietnam primarily through harm reduction programmes involving increased availability of condoms and needles/syringes, coupled with behaviour change communication and advocacy work. The project covered 21 provinces. This project ran till 2009 and was found at the time of end-of-project evaluation to have been very successful. The World Bank launched its own “HIV/AIDS Prevention Project for Vietnam” in 2005 with a credit of US$38.5 million. This provided more comprehensive support for a range of prevention and treatment activities in 18 provinces, some of which overlapped with the DFID provinces, as well as national components on policy studies and research, training, and innovation. In 2009 when DFID was designing a follow-on project, it was decided to add resources to the existing WB project, instead of having another stand-alone DFID project. DFID added another £18.3 million grant to the WB project, which was extended until the end of 2012. The two sets of provinces were combined, making 32 provinces. These include most of the provinces with highest HIV transmission rates. A requirement of the DFID funding was that 60% of the combined project resources must be allocated to harm reduction activities. 4 Vietnam also currently receives significant funding for HIV and AIDS programmes from the US Government (PEPFAR) and from the Global Fund Round 9. PEPFAR is Vietnam’s largest HIV donor in financial terms, although the programme is focused in a smaller number of provinces and spends most of its resources on treatment (including AIDS treatment and methadone) and on technical assistance and policy work. PEPFAR supports the social marketing of condoms in some provinces. PEPFAR cannot support comprehensive harm reduction among PWID because of US Government restrictions on procuring and distributing needles/syringes. PEPFAR is now reducing its budget in Vietnam much faster than originally planned, and is currently transitioning from a focus on programme delivery to a focus on technical assistance. The Global Fund has been supporting harm reduction programmes on a smaller scale than DFID/WB and generally in lower transmission areas. When Round 9 funding was approved, it was agreed that when it enters its Phase 2 it would take on much of the harm reduction work supported by DFID/WB. 2012 was to be the transition year, with full support from 2013. Vietnam was also planning to submit an application for major HIV/AIDS funding under Round 11. However, due to the Global Fund’s own financial problems, Round 11 was cancelled and the transition to Phase 2 of Round 9 is no longer fully assured. The Phase 2 application process has become more rigorous, is subject to new conditions and is therefore, even if successful, going to be delayed. In the meantime, the planned gradual transition of DFID/WB-funded harm reduction activities to Global Fund financing in 2012 has not taken place, although some smaller programme components (the STI treatment programme and the VCT programme) have been transferred. There are also much smaller AusAID and ADB projects covering a handful of provinces in Vietnam. Domestic funding for HIV and AIDS is very low, at around 13% of the total, less than half of which is provided by central government. The Vietnam Authority for HIV/AIDS Control (VAAC) lobbied successfully with the Government leadership to have HIV/AIDS included as a new National Targeted Programme from 2012. However, the National Assembly cut back the proposed budget for 2012 by 50% due to nationwide budget constraints and a widespread sense among politicians that HIV is not a high priority, being primarily a disease associated with “social evils”. Vietnam has committed to increasing central government funding for HIV/AIDS from the current level of $10m per year by 20% per annum up until 2020. This compares to current total programme expenditure of about $125m, with an estimated need of about $200m by 2020. Nevertheless it is a great improvement on the previous central government financial contribution of less than $7m per year up to 2009. According to a recent study by AusAID, Vietnam currently has the third lowest domestic funding proportion for HIV work in Asia, after Timor Leste and Laos. An increasing proportion of domestic funding is allocated by provincial governments. Provincial financing of HIV and AIDS programmes grew by 85% from $6.6 million in 2008 to $12.2 million in 2010. As Vietnam follows a path of increasing fiscal decentralization, this trend is likely to continue. According to the most likely future funding scenario, GoV financing will overtake donor financing by 2015/16 and will cover over 60% of the estimated total need by 2020. Given that there are likely to be savings through gradually increasing efficiencies, current GoV estimates of total programme need are probably a little on the high side. So the actual funding gap may not be insurmountable from 2015 onwards, especially if Vietnam is successful in obtaining additional Global Fund financing when new applications are accepted from 2015 onwards. Annex 1 shows in both narrative and graphic terms the various future funding scenarios with and without the DFID extension and with and without additional Global Fund financing. The DFID extension plays two critically important roles: (1) it bridges an inevitable funding gap in 2013; and (2) more importantly ensures continuity of vital prevention activities, which would otherwise be interrupted for several months with disastrous consequences for the epidemic. Provided that the Global Fund approves the Phase 2 of Round 9 and can provide new funding for Vietnam from 2015 to 2020, it looks as though Vietnam’s future funding needs can be met. 5 Justification for a 1-year extension to the existing project Given the above background, DFID Vietnam proposes to allocate additional funding to the existing project and extend it for one year to the end of 2013. The reasons are: 1. This is a very effective project which has achieved significant demonstrated impact on the course of the epidemic in Vietnam. DFID Vietnam has available financial resources to extend it. 2. Vietnam is facing an unprecedented and unexpectedly rapid reduction in donor financing for HIV and AIDS control. While domestic funding is increasing steadily, it cannot fill this large gap so quickly, although it could expect to do so from about 2020. It is hoped that the Global Fund can fill the gap from 2015 to 2020. 3. Because of recent changes in the Global Fund, there is likely to be a 6-month gap in financing in the first half of 2013, just when the current DFID/WB project would have finished. This will almost certainly lead to a disastrous interruption of crucial prevention programmes, which will result in a resurgence of HIV infections, especially among PWID, bringing to a halt Vietnam’s progress towards HIV control and severely damaging the legacy left by 10 years of DFID support. 4. The Government of Vietnam has formally requested DFID to extend the project, and this is strongly supported by international partners in country, including USG and the UN agencies. During the extension period the Government will use the project resources even more intensively than before to develop cost-effective, sustainable approaches to HIV prevention that can make maximum use of limited domestic resources and also make much more use of the private sector. Strategic fit with DFID priorities in Vietnam DFID formulated its Operational Plan in early 2011 with the following priorities, which are fully embedded in the FCO-led UK-Vietnam Strategic Partnership: Support achievement of the MDGs, particularly off-track ones and areas with less progress Step up wealth creation efforts by supporting Vietnam to benefit from global trade agreements and achieve a growth path that is more private sector led Enhance support on governance and accountability Address challenges for women and girls, who will benefit from many of our programmes: creating jobs, raising minimum incomes and pensions (social protection), and providing access to education Support the Government to address climate change challenges by enhancing the Government’s technical expertise, coordination capacity, and by mainstreaming climate resilience This HIV project primarily supports the first priority. MDG6 on communicable diseases is one of very few that are still off-track in Vietnam. There are signs that Vietnam is now turning the corner on HIV control. The MDG target states that the spread of HIV should have started to be reversed by 2015. This means that the national HIV prevalence rate needs to be in decline. The number of new HIV cases detected every year (a proxy for the incidence rate) has been in decline for four consecutive years, but prevalence is not yet decreasing, as there are sufficient numbers of AIDS patients on ARV treatment to ensure that the AIDS-related death rate is also declining. In order to meet the MDG, the incidence rate still has to come down further, and this can only be achieved by continuing and if possible intensifying the current prevention programmes among most-at-risk populations. The project also supports the 2nd and 4th priorities. It encourages private sector development by shifting the supply and distribution of commodities (condoms, lubricants, needles/syringes) away 6 from free public sector channels to commercial or partially subsidized private sector channels. It empowers and protects women and girls. Sex workers are both empowered and protected by having access to condoms and by being trained through their interaction with the project to be able to negotiate successfully with their clients to ensure 100% condom use. Female partners of PWID and MSM are protected from HIV infection when their male partners use safe sex and safe injecting practices. B. Impact and Outcome that we expect to achieve The project will maintain the downward momentum of HIV prevalence among PWID. By the end of 2013 prevalence among PWID should be reduced to below 13%. Without this project extension, further progress in reducing HIV transmission among PWID would be very unlikely and in fact transmission could start to rise again, due to non-availability of clean needles/syringes when and where they are needed by PWID and due to the discontinuation of the peer educator network. Peer educators play a key role in identifying new PWID and getting them to adopt safe injecting practices. The project will reduce dependence on the supply of free clean needles/syringes through Government by developing innovative approaches through the private sector. Some provinces are already piloting such approaches, and these will be scaled up rapidly during 2013. The project will also continue to ensure that HIV prevalence among FSW is maintained below 3%. For the past decade, prevalence among FSW has been fluctuating around 4% after a high of 6% in 2002, but dropped below 3% in 2011. Prevalence among FSW locked up in detention centres has generally been higher, around 7-8%, but the Government has now stopped sending sex workers to compulsory detention centres. This will greatly improve the access to HIV prevention services by all sex workers. Following the new model implemented since the beginning of 2012, the project will continue to shift the primary distribution route of condoms away from dependence on free condoms provided by the Government to a greater reliance on the private sector, especially ensuring that high quality condoms are widely available at an affordable price in all the venues where sex transactions take place. The project will also continue to develop effective approaches in a sub-set of 10 provinces aimed at reversing the current increasing trend of HIV prevalence among MSM. Surveys in the supported provinces should indicate no further rise in prevalence among MSM. This will be achieved through strengthening MSM self-help networks and organizations, continuing to support peer educators and ensuring an adequate supply of appropriate condoms and lubricants, primarily through the private sector. In order to achieve this three-fold impact, the project needs to be able to ensure low levels of highrisk behaviours among the three primary target groups of PWID, FSW and MSM. Specific targets for the extension period are: (1) consistent use of clean needles by people who inject drugs maintained at over 80% in the 32 participating provinces; (2) consistent use of condoms by female sex workers maintained at over 90% in the 32 participating provinces; (3) consistent use of condoms by men who have sex with men brought up to over 60% in the 10 provinces targeted for this work; (4) 2,200 patients are retained on methadone maintenance therapy. In order to help achieve these results the project will provide in 2013 22 million needles/syringes and over 42 million condoms. 7 Appraisal Case A. What are the feasible options? The first consideration is whether DFID should do anything further to help Vietnam achieve progress towards the HIV MDG. 10 years of support will come to an end, as planned, in December 2012. However, as outlined in the Strategic Case, this will almost certainly lead to a discontinuation of crucial HIV prevention activities in 2013, due to the situation Vietnam finds itself in with less money than expected coming in from both the Global Fund and PEPFAR. This would most likely lead to a resurgence of HIV infections, especially among PWID, bringing to a halt Vietnam’s progress towards HIV control and severely damaging the legacy left by 10 years of DFID support. Due to underspend in other areas of the DFID Vietnam-Cambodia portfolio, DFID Vietnam has available financial resources to reallocate. Considering the significant impact that the DFID-funded HIV work has had to date, as evidenced by the 2009 independent project evaluation of the earlier project (conducted by WHO) and by the 2011 independent impact evaluation of the DFID-funded harm reduction work (conducted jointly by UNAIDS and the University of New South Wales), further investment in HIV control appears to be the most cost-effective way for these available resources to be allocated. There is no other project in DFID Vietnam’s past or present portfolio that has had such a demonstrable impact on achieving progress towards any of the MDGs. If DFID money is to be used to help Vietnam maintain progress towards the HIV MDG, as set out in the Strategic Case, the options for the approach are: 1. Design a new intervention, building on past successes and learning from less effective aspects of previous work. 2. Provide funding to other international partners operating in Vietnam, such as the UN agencies or other bilateral donors, to increase the scope of their own work using DFID resources. 3. Extend the current project, using the existing management and implementation mechanisms, but with a tailoring of the activities to be supported to maximise both impact and sustainability. B. Assessing the strength of the evidence base for each feasible option In the table below the quality of evidence for each option is rated as either Strong, Medium or Limited Option 1 2 3 Do nothing Evidence rating Strong Medium Strong Strong What is the likely impact (positive and negative) on climate change and environment for each feasible option? This project does not offer any opportunities under any of the options to do any significant work on climate change and the environment. However, there is a medium level environmental risk presented by the disposal of used condoms and especially needles/syringes, which may be HIV infected. As with previous DFID-funded work, steps will be taken to mitigate the risk by ensuring, as far as is possible, safe disposal of used commodities, especially needles/syringes. 8 Categorise as A, high potential risk / opportunity; B, medium / manageable potential risk / opportunity; C, low / no risk / opportunity; or D, core contribution to a multilateral organisation. Option 1 2 3 Do nothing Climate change and environment risks and impacts, Category (A, B, C, D) B B B C Climate change and environment opportunities, Category (A, B, C, D) C C C C C. What are the costs and benefits of each feasible option? The “do nothing” option has no cost to DFID, but would in effect have substantial negative benefit. Although clearly some of the previously achieved benefits are “banked” in terms of HIV infections averted over the past several years, the lasting benefit of setting up an HIV prevention system that ensures a continuing low (and reducing) HIV transmission rate would be largely lost due to interruption of key services, disbanding of thousands of peer educators and stock-outs of key commodities, especially needles/syringes. This would lead to an almost certain reverse of progress made so far in HIV control in Vietnam. Options 1 and 3 would focus on harm reduction activities among the three most-at-risk population groups (PWID, MSM and FSW). The cost-effectiveness of reducing new HIV infections through harm reduction programmes has been tested and found effective in many global settings. The UK has been a global leader in this area. In concentrated epidemics such as that in Vietnam (i.e. where the HIV prevalence rate is still low among the general population but high among most-at-risk subpopulations), harm reduction is by far the most cost-effective approach. The latest global research by the UN indicates that this should be supplemented by better integration of prevention and treatment programmes with the aim of detecting HIV positive people earlier and getting them onto ARV treatment earlier, thus reducing their infectiousness (i.e. “treatment as prevention”). The original project design conducted an in-depth cost-effectiveness study, looking at three possible approaches: (1) comprehensive prevention programme with emphasis on harm reduction in highest transmission provinces; (2) similar programme but without the geographical targeting, to ensure equity; and (3) harm reduction programme with narrower focus on outreach by peer educators and condom/needle/syringe distribution. The analysis found that the first approach was the most costeffective, providing a net return on the DFID investment of between £26 million and £59 million. The societal benefit would range from £1.86 billion to £4.39 billion. The return on DFID investment only factors in healthcare costs of the averted HIV infections. The societal benefit also considers the economic cost of lost productivity, quality of life and mortality. Option 1 would allow better fine-tuning of DFID resources to ensure that all money was spent on the most cost-effective interventions. This could include cutting support to some provinces and focussing resources in the provinces where the most new infections are likely to occur, and possibly adding some high-transmission provinces not currently supported by DFID/WB (e.g. Dien Bien which now has the highest prevalence in Vietnam, and rising). However, this would involve an extensive redesign process which would take time and staff resources, which are in very short supply. DFID resources must be fully spent by December 2013 when the MDGs programme in Vietnam comes to an end, as agreed by Ministers. This is not therefore a practical option. Option 2 offers very limited opportunities. The only like-minded donor in Vietnam in terms of prioritizing harm reduction activities is AusAID. They have a small programme, limited management resources and no plan to expand in Vietnam. DFID resources could be managed by USAID, but their programme does not prioritize harm reduction, has very high management costs and would not be 9 allowed to procure needles/syringes – a critical component. DFID is already funding HIV advocacy work and technical assistance through the “One UN” project, which runs till 2014. The UN would find it very difficult to manage large service delivery components such as the needle/syringe programme, the methadone programme and the condom social marketing programme. So the only practical option is to continue to work with the World Bank, which is option 3. The original economic appraisal has been revisited, re-examining the costs and benefits of the harm reduction programme among PWID as proposed under option 3 and comparing this with the “do nothing” option. This new appraisal estimates the net present value of benefits to DFID to be £5.8 million for the proposed additional investment of £6.2 million, and the net present value of societal benefits to be £220 million. So even if the only benefits are from the work among PWID, the investment is strongly justified. However, the extension is expected to deliver additional benefits from the work among sex workers and among MSM. Due to a severe paucity of economic evaluations of condom programmes globally, it is not possible to do this analysis for Vietnam without commissioning a major new stream of research. Nevertheless, there is overwhelming non-economic evidence, well accepted by the global development community, including UNAIDS, US CDC and WHO, that 100% condom use programmes are an essential ingredient of any HIV prevention strategy in both generalized and concentrated epidemics. The revised “light touch” economic appraisal is attached at Annex 2. Option 3 is therefore the preferred option. Within option 3 there are further options as to how to allocate the resources. Despite this not being a new project offering maximum opportunities to allocate resources completely rationally based on the most effective targeting of the appropriate mix of interventions, the working relationship between DFID, World Bank, the WHO technical advisers and VAAC is such that a very good prioritization of activities can be achieved within the existing project. Resources are effectively allocated using a theory of change process, somewhat modified by political realities. The theory of change looks at interrupting HIV transmission routes and focussing resources at the activities that will have the greatest effect on interrupting the key transmission routes. Transmission among MSM, transmission from MSM to the general population and transmission from FSW to the general population are all interrupted by consistent condom use. Transmission among PWID (the most efficient HIV transmission route) is interrupted by ensuring zero sharing of injecting equipment. Transmission from PWID to the general population and to other high-risk groups (FSW and MSM) is interrupted by ensuring 100% condom use. However, it is recognized that ensuring 100% condom use within long-term stable relationships is very difficult to achieve, so the project primarily targets the highest risk sexual activity, i.e. transactional sex, sex with multiple partners and anal sex between men. The theory of change for the specific interventions to be supported can be illustrated by the following diagram: 10 FSW Clients Of FSW PWID Regular & casual partners of PWID MSM General population MSW Clients of MSW Female partners of MSM Most-at-risk population groups are at the left. The general population is at the right. The arrows represent HIV transmission routes. The thicker arrows show more intense transmission. The blue arrows are routes of transmission specifically targeted by the 100% condom use programme. The red arrow is the transmission route addressed through the needle/syringe and methadone programmes. The areas of overlap between different most-at-risk populations have particularly high risk of transmission. These are addressed by both types of programme. The black arrows represent routes of transmission that are difficult to target, and so are not a major focus of the project. It is important to address the intra-group transmission among PWID and MSM, because this reduces the pool of HIV infected people within the groups, thereby reducing the risk of transmission out from each group. The intensity of HIV transmission along each route is reduced by three interventions: (1) reduce the frequency of high-risk behaviour; (2) eliminate or greatly reduce the risk from the high-risk behaviour; and (3) reduce the infectiousness of the HIV-infected people by treating them with ARVs to reduce the viral load in their blood. It is not generally possible to implement intervention (1) for sexual behaviour, although if sex workers are able to earn enough money seeing fewer clients this does reduce the risk of infection. Sex workers who have sex with several clients a day are much more likely to receive and pass on the virus. For PWID, methadone eliminates or greatly reduces the need to inject drugs (as methadone is administered orally). 11 The primary focus of the project is on intervention (2). 100% condom use and 100% use of clean needles/syringes almost completely eliminates the risk of HIV transmission. However, since it is never possible to reach 100%, attention also needs to be paid to interventions (1) and (3). The “Treatment 2.0” pilot addresses intervention (3). Treatment as prevention is a relatively new intervention globally and Vietnam has agreed to pilot it, initially in two provinces. The effectiveness of combined prevention activities among PWID and FSW was confirmed by the independent “Evaluation of the epidemiological impact of harm reduction programs on HIV in Vietnam” conducted jointly by UNAIDS and the University of New South Wales and published in 2011. Epidemiological modelling in six of the 32 supported provinces estimated that an average of over 1,500 HIV infections were being averted annually through the free distribution of needles/syringes and condoms just in these 6 provinces and not including commercially or socially marketed commodities. When these estimates are extrapolated across the 32 provinces, and assuming a similar pattern continued in subsequent years, it suggests that this intervention more than accounted for the total annual reduction in new HIV infections in Vietnam since 2008, when the downward trend started. In other words, without this DFID/WB supported programme, the number of new HIV infections in Vietnam would still be increasing today. DFID resources in 2013 will therefore be allocated first and foremost to comprehensive harm reduction programmes in the 32 supported provinces. This accounts for 60% of the proposed budget. The political reality is that provinces cannot be cut out of the project at this stage, although more resources are allocated to provinces that have greatest need and have a good track record of using the money most effectively. Some resources are allocated to surveillance, monitoring and evaluation (4.5%) to training and advocacy (15%) and to international technical assistance (7.5%). These are necessary to improve the prospects of sustainability. Hitherto, most of Vietnam’s fight against HIV/AIDS has been undertaken by internationally funded projects, albeit under the administrative leadership of the Vietnam Administration for HIV and AIDS Control (VAAC). International partners have provided most of the technical inputs, including clear steers on where and how money should be spent. The capacity to lead and manage the response at the national level has been strengthened, but this capacity is not yet well developed in most provinces. This is why more investment is needed over this extension year of the project to provide more intense training to officials at local levels to ensure that ongoing technical leadership can be provided domestically without dependence on international projects. This particularly includes the ability to collect and analyse data and use it for evidencebased programming decisions, especially as an ever-increasing proportion of resources will be allocated by provincial governments. DFID and the World Bank will continue to work closely with other international partners over the extension period to build the evidence base and advocate with key Government counterparts at national and provincial levels with the aim of increasing Vietnam’s domestic budget allocation for HIV and AIDS and ensuring that the scarce resources are allocated to the most cost-effective activities. The remaining 13% of the proposed budget is for project management by the Government at national level and in the 32 provinces. This proportion has been reduced below the previous level, again with a view to achieving sustainability. D. What measures can be used to assess Value for Money for the intervention? The ultimate measures of value for money are in the cost per HIV infection averted and the resultant economic returns in terms of (direct) medical costs averted and (indirect) societal costs averted. These will be assessed again during the independent evaluation planned for the second half of 2012 and can be compared to international benchmarks. 12 During the period covered by the UNAIDS/UNSW epidemiological impact evaluation mentioned above, coverage of the most-at-risk populations within the selected study provinces was not very high (less than 50% of both PWID and FSW and very few MSM indeed). Furthermore, rates of unsafe behaviour (sharing needles and unprotected sex) remained fairly high. Since then coverage has improved significantly (although still needs to improve more) and levels of unsafe behaviour have reduced dramatically in the supported provinces. These factors would suggest that the value for money in terms of HIV infections averted will be even greater now than it was then. This is because with generally lower levels of unsafe behaviour and generally greater penetration of the most-at-risk populations, the same programmatic investment is likely to result in a greater proportion of HIV infections averted. Lower coverage tends to include the easier-to-reach communities, whereas higher coverage includes harder-to-reach communities who typically practise higher risk behaviours. The current project (unlike the one previously evaluated) has both higher coverage and higher rates of consistent safe behaviour. E. Summary Value for Money Statement for the preferred option The proposed extension represents very good value for money. The societal economic rate of return is one of the highest of any potential DFID funded project anywhere. This was estimated at over £4 billion from the original £18.3 million investment, and it is now estimated that at least an additional £220 million of societal benefits would be generated from this extension phase. The net present value of direct benefit to DFID (in averted health sector costs) is £5.8 Million. Commercial Case Direct procurement Almost all the procurement will be indirect (see below). A small proportion of the money (£250,000) is retained by DFID for direct procurement of some international inputs, especially for training, monitoring and evaluation. Such procurement follows DFID procedures to ensure value for money. Indirect procurement A. Why is the proposed funding mechanism/form of arrangement the right one for this intervention, with this development partner? Most of the procurement in the project is done by the Central Project Management Unit (CPMU) and its provincial subordinates (PPMUs). These are Government of Vietnam units, so the aid modality is classified as Financial Aid to the Government of Vietnam. Procurement is undertaken using Government of Vietnam procurement procedures. Some procurement is done by the World Bank office in Hanoi following the World Bank’s procurement regulations. All indirect procurement in the project, whether through Government or World Bank, must follow World Bank procedures and is subject to monitoring and audit accordingly. Procurement to date has been satisfactory according to the World Bank procurement specialist. The project was selected for various audits and evaluations by the UK Government, including DFID’s Internal Audit Department in 2010 and NAO audit in 2011. There were no qualified audit opinions. 13 Given the nature of this final year during which the project activities are going to be transferred gradually to the National Targeted Programme or other donor funded projects, the need for the procurement work to follow Government procedures becomes greater. Therefore the project will help strengthen the procurement processes by officially implementing at all levels the transparent procurement framework that has been applied successfully in other DFID/WB funded work in Vietnam. The CPMU and PPMUs are already implementing most of the steps in this framework effectively. B. Value for money through procurement A realistic procurement plan for the remaining contract activities has been prepared by the PPMUs, consolidated by CPMU, and approved by MOH. Procurement supervision missions will be carried out on a semi-annual basis. Procurement of goods and services will be on a competitive bidding both internationally and nationally, depending on the size of goods and service packages. Financial Case A. What are the costs, how are they profiled and how will you ensure accurate forecasting? The phased budget for the additional financing is as follows: Description FY 2012/2013 FY 2013/2014 Total Trust Fund with the World Bank £ 4.3 m £ 1.65 m £ 5.95 m DFID managed consultancy £ 0.2 m £ 0.05 m £ 0.25 m Total £ 4.5 m £ 1.7 m £ 6.2 m The project will start its planning process for 2013 in Oct/Nov 2012 in consultation with all key stakeholders including provinces, central agencies and donors. Final provincial action plans and the overall project workplan will be approved by 31 Dec 2012. DFID forecasting is based on these workplans. Payment to the Trust Fund with the World Bank will be made twice in FY12/13, scheduled in Dec 2012 and Mar 2013 to align with the payment schedule of the project. There will be one payment in FY13/14, scheduled in Oct 2013. Based on preliminary estimates, to be confirmed during the above-mentioned planning process, indicative financial allocations to the different areas of work will be as follows: £1,240,000 for harm reduction for people who inject drugs, including needle/syringe programmes and methadone maintenance therapy (for 9 months with transition to Global Fund starting from July 2012) £2,052,000 for condom social marketing £437,000 for work among men who have sex with men £282,000 for strengthening the national monitoring and evaluation system for HIV and AIDS £1,142,000 for training and advocacy (including £210,000 for technical assistance provided by WHO experts) £797,000 for programme management (at central level and in the 32 provinces) £250,000 for DFID managed consultancy 14 B. How will it be funded: capital/programme/admin? Programme. C. How will funds be paid out? The project utilizes a joint financing/payment arrangement whereby DFID and IDA funds are comingled and channeled through a special account held by the Ministry of Finance. The Administrative Arrangement between DFID and the World Bank and the Grant Agreement between the World Bank and the Government of Vietnam will be amended to reflect the time and cost extension in the funding. The World Bank is not committing additional funds for this time extension period, but has agreed to extend the Trust Fund to enable DFID to finance another year of operations. DFID will then transfer the funds to the World Bank according to the above schedule, but taking into account actual progress of the planned activities to ensure that funds would not be transferred in advance of need. From the Special Account, the funds would be transferred to CPMU and PPMUs. D. What is the assessment of financial risk and fraud? No fraud or misuse of funds has been detected during the operation of the project so far. The monitoring arrangements both of the Government and of the World Bank are robust. The fiduciary risk is considered to be low. E. How will expenditure be monitored, reported, and accounted for? The assessment for the additional financing has concluded that the project will continue to meet the minimum World Bank financial management requirements. Current reporting arrangements will be maintained. PPMUs are committed to improving financial management and reporting and are following up on 2010 and 2011 audit recommendations. The CPMU will continue their frequent monitoring visits supported by two WHO technical consultants to provinces and will send to donors six-monthly progress reports which cover up-to-date information on disbursement and work progress. Besides annual financial and reporting audits, an impact evaluation will also be carried out in 2012. Management Case A. What are the Management Arrangements for implementing the intervention? The programme will be managed by the Vietnam AIDS Administration Control (VAAC) under the Ministry of Health. Management and coordination will be organized as follows: A Joint Steering Group (JSG), chaired by the former Vice Minister of Health (now a Special Adviser to the Ministry), sets strategic goals, approves the annual work plans and budget, and oversees implementation. Members include officials from VAAC and ODA management Ministries (MPI, MOF), WHO (technical review), World Bank and DFID. The JSG meets twice a year. 15 A Central Programme Management Unit (CPMU) is in charge of programme management. The CPMU is led by a Deputy Director General of VAAC with support from seconded staff from VAAC and contracted staff. A Technical Review Team (TRT) will review the annual work plans and provide support as necessary. TRT comprises of technical experts from implementing Ministries, WHO and technical epidemiology institutes. At provincial level the Provincial AIDS Centre (PAC) is in charge of developing and reviewing provincial work plans and facilitating implementation by ensuring support and participation of multiple implementing agencies. It is led by the Vice Chairman of the Provincial People’s Committee and attended by senior officials from Departments of Health, Public Security, Labour and Social Affairs, Planning and Investment, Finance, Information and Culture, Women’s Union and the Youth Union. Provincial action plans are approved through an iterative process involving the PACs and the CPMU, with technical advice from WHO. DFID and the World Bank have opportunities to feed into this process. Technical assistance will be provided by WHO. Additional TA will be procured based on demand. DFID and the World Bank jointly lead on overall management, although the World Bank handles the financial disbursement to the Government and also leads on procurement. Both DFID and the World Bank participate in regular supervision and monitoring. The programme will contract health specialist inputs through a Technical Assistance Arrangement, which will include drawing in WHO expertise. DFID plans to bring in additional technical inputs as required to support annual reviews. Day-to-day implementation management is by the Government of Vietnam at both national and provincial levels. During this extension phase the management costs have been reduced by rationalization of management structures at provincial level and reduction of staff numbers at the national level. More staff will now be paid for completely by the Government. International partners in the HIV/AIDS sector in Vietnam work together closely, and the DFID/WB project is not managed as a stand-alone project. It is essential for effectiveness and sustainability that it is managed in close collaboration with the programmes funded by the Global Fund and by PEPFAR and with the domestically funded National Targeted Programme. Donors hold monthly coordination meetings and both DFID and the US Government are members of the Global Fund’s Country Coordinating Mechanism, along with UNAIDS and WHO. B. What are the risks and how these will be managed? The overall risk rating is medium. The two key risks identified during the original project design – sustainability of outcomes and support from public security – remain key risks, although recent political developments have somewhat reduced the second of these. Limited sustainability of outcomes due to shortage of public funds. This remains a key risk. Government commitments to increase significantly the domestic budget for HIV and AIDS have only partially materialized and in the meantime donor support has decreased much more rapidly than previously expected. Uncertainties over ongoing Global Fund financing are particularly worrying. This risk will be mitigated in the short term by this project extension, ensuring uninterrupted prevention activities during the transition to the next phase of Global Fund financing. DFID and other international partners will continue to use high level policy fora to push for increasing public funding for HIV/AIDS and make the economic case for early funding on prevention and harm reduction. As GoV financing is expected to grow steadily over the coming years, the situation from 2020 onwards looks manageable. The period from 2015 to 2020 could potentially be covered by additional Global Fund financing, since the Global Fund Board has stated that new funding applications will be processed from 2015. International partners, including key Global Fund financiers such as DFID and the US Government, need to advocate at the Global Fund Board and senior management level to ensure that the Global 16 Fund provides adequate resources for Middle Income Countries (especially lower MICs like Vietnam) which are struggling to mobilize adequate domestic resources while simultaneously losing bilateral donor funding. Restricted community and authority acceptance of the national harm reduction approach. Despite the growing awareness of the effectiveness of harm reduction among Government agencies and communities in Vietnam, drug injecting is still treated as a criminal offence by many local authorities and police forces. While this remains the case, harm reduction activities such as needle and syringe programmes may not receive the necessary support from communities and Government agencies, in particular the police. Furthermore, local authorities at various levels (from provincial down to commune) in some parts of the country place restrictions on the placement of condoms in entertainment venues and guesthouses, despite the fact that there is a national regulation encouraging such condom placement. This severely hinders the 100% condom use programme in those locations. To mitigate this risk, the programme will actively pursue a multi-sectoral approach to the management and delivery of project activities. In addition to national support from the MOH, Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Labour Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA) and Ministry of Culture Sports and Tourism, the political involvement of provincial, district and commune level party and local governments (i.e. People’s Committees) will be prioritized. Lack of procurement capacity was identified as an important risk in the original project design, and this proved to have been a well-founded concern. Stock-outs of commodities occurred during the transition from previously DFID-funded provinces to the new project using World Bank procurement rules in 2009-2010. Provided that option 3 (continuation of the same joint DFID/WB project management arrangements) is selected, this should not be a major risk now, as all provinces are now up to speed on the procurement regulations. Stigma, discrimination and criminalisation of drug users, sex workers, MSM and other vulnerable groups was another important risk. This continues to be a risk, although the criminalization of sex work has reduced markedly and in many provinces drug users are less criminalized than before. MSM remain highly stigmatized almost everywhere, although there are signs that this is beginning to change in the major cities. Furthermore, the Ministry of Justice is currently reviewing the legal status of same-sex couples, using (somewhat surprisingly) a rights-based approach to identity, property, inheritance and adoption of children. The project will continue to work with government officials and community leaders to reduce criminalization, stigma and discrimination. C. What conditions apply (for financial aid only)? Not applicable. D. How will progress and results be monitored, measured and evaluated? The project currently utilizes a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework which forms part of the National M&E Framework which the project has helped to develop. Outcome and output indicators have been revised to make them up to date and relevant and to reflect the additional results to be delivered through the extension phase. The project has established a good monitoring and reporting system. Monitoring is carried out at different levels by: Ministry of Health and VAAC (ad hoc) Provincial AIDS Centre (monthly) Central Project Management Unit M&E team (6-monthly) Technical, financial, social and safeguard audits (annually) 17 The CPMU provides VAAC and donors with a 6-monthly progress report with data on progress on disbursement, on progress of implementation, on procurement and TA activities and key issues to be addressed. These reports will be discussed at the semi-annual review missions. The project also uses data from the Government’s Annual Sentinel Surveillance Data System and the Integrated Blood and Behavioural Survey (IBBS) (every 2-3 years) and supplemented by programme surveys at start and completion of the project. The project has used analysis and evidence from various evaluations on DFID’s work on harm reduction including the independent evaluation in 2009 on DFID’s previous project by WHO and the independent impact evaluation in 2011 by UNAIDS and the University of New South Wales. The project is planning another independent evaluation focusing on effectiveness and VFM. This is currently in the process of being commissioned. The ToRs have been developed jointly by DFID Vietnam, DFID Evaluation Department, WHO and the World Bank, in consultation with VAAC and following UNAIDS guidance on best practice for HIV prevention evaluations. The evaluation will be conducted in close collaboration with the independent Vietnamese team (from the Research Centre for Rural Population and Health) that is providing inputs to the World Bank’s Implementation Completion Report. The project has also included a budget of £282,000 during the extension phase to strengthen the national monitoring and evaluation systems for HIV and AIDS. Logframe Quest No of logframe for this intervention: 3623917 18 Annex 1 Supplement to Business Case: Funding sources, current and future 1. Funding from all sources over the last three years for which comprehensive data is available is presented in the table below. (Figures in US dollars) Sources % 2008 2009 2010 Total 13,459,880 17,176,061 21,431,087 52,067,028 6,832,580 6,737,254 9,193,116 22,762,950 6.3% 6,627,300 10,438,807 12,237,971 29,304,078 Private sources 16,014,322 16,036,519 15,600,379 47,651,220 8.1% 13.1% Profit-making institutions Households 82,581 15,931,741 144,812 15,891,707 15,600,379 227,393 47,423,827 International sources 66,734,575 94,161,904 102,221,779 263,118,258 Bilateral organisations Government of Australia Government of Canada Government of Denmark Government of France Government of United Kingdom 48,552,930 1,205,251 70,785,002 2,471,859 137,207 954,800 593,146 4,470,027 598,866 2,256,690 84,013,483 1,502,842 300,000 4,176,787 321,443 7,534,127 203,351,415 5,179,952 437,207 5,131,587 1,513,455 14,260,844 56.0% 1.4% 0.1% 1.4% 0.4% 3.9% Government of United States (PEPFAR) 38,894,158 63,926,353 69,340,357 172,160,868 47.4% 596,419 304,091 581,876 953,162 158,084 398,397 385,379 448,912 117,000 502,195 159,897 754,503 819,488 1,469,450 1,561,971 0.2% 0.2% 0.4% 0.4% 3,255 58,835 62,090 0.0% 17,849,999 6,251,409 22,975,232 6,320,161 17,512,495 6,152,088 58,337,726 18,723,658 2,871,788 5,829,561 6,650,517 15,351,866 1,877,157 5,548,183 1,670,997 8,443,611 1,343,508 1,849,216 4,891,662 15,841,010 4.2% 1.3% 4.4% 1,301,462 710,902 1,517,166 3,529,530 1.0% 331,646 401,670 695,801 1,429,117 0.4% The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation 46,697 20,887 67,584 0.0% Ford Foundation Other international not-for-profit organisations 14,880 14,880 0.0% Public sources Central government (including National Targeted Program) Provincial government Government of Germany Government of Ireland Government of Netherlands Government of Sweden Other Goverments (Japan, Luxembourg, Norway) Multilateral organisations Asian Development Bank (ADB) Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) UN agencies World Bank Multilateral funds or development funds n.e.c. International not-for-profit organisations Total 14.3% 0.1% 13.1% 72.5% 16.1% 5.2% 331,646 340,093 674,914 1,346,653 0.4% 96,208,776 127,374,483 139,253,245 362,836,506 100.0% 19 2. The above data is derived from the Vietnam National AIDS Spending Assessment (UNAIDS, 2011). After excluding out-of-pocket expenditure, the total programme expenditure covered by Government and donors in 2010 was $123.7 million. 3. The Government estimates that the total programmatic need is still around $125 million, but from 2014 this will grow steadily to $205 million by 2020. This growth is due to planned increased coverage, both of prevention programmes and treatment and care programmes, as Vietnam seeks to fulfil both its international obligations and its duty of care to the population. 4. Many of the donors listed in the above table have already stopped providing any further funds for HIV and AIDS work in Vietnam. These include most of the European donors, the World Bank and the ADB. The WB and ADB have decided that any further funding for the health sector should be through health systems strengthening, not for any specific disease control programmes. 5. Although PEPFAR is by far the largest donor, there are some important considerations concerning PEPFAR funding that make it very different from other donors’ and GoV funding. Hence the role of PEPFAR in the overall financial picture is distortionary. Key factors include: a. Almost all PEPFAR money is channelled through US-based international NGOs and cannot be passed through Government channels and cannot pay for Government staff or Government-managed procurement. b. Almost half of the money goes into management, administrative and “enabling” work that does not directly deliver HIV/AIDS services. c. PEPFAR cannot fund some crucial prevention activities, such as needle and syringe programmes. d. PEPFAR’s cost norms (e.g. for staff salaries and allowances) are three times those of the Government. 6. The Government has recently published (this week) its latest projections for the HIV/AIDS response’s financing needs, using an all-inclusive programmatic approach sub-divided into four categories: prevention, treatment & care, monitoring & evaluation and capacity building. These projections are based on the Government’s own cost norms and management costs. Whereas the DFID/WB and Global Fund financed programmes stay quite close to Government cost norms, as they mainly implement through Government, PEPFAR’s cost structure is very different. Thus, to get a comparable picture of the actual value to Vietnam of the PEPFAR programme, the PEPFAR budget has to be adjusted downwards to fit with GoV cost norms for the activities financed. This makes a very significant difference when looking at future financing projections and the estimated funded gap. The following two figures illustrate this. 20 Figure 1: Showing funding sources without adjusting PEPFAR value. (US$) 7. This assumes that the Global Fund Round 9 grant Phase 2 application is granted and does not include the DFID extension. At face value, the programme is fully funded until 2015 or 2016. However, this is not a realistic scenario, because the PEPFAR resources cannot be used to fund all the activities considered necessary by Government (and donors) and PEPFAR-funded and managed activities cost approximately twice as much to implement as Government-managed activities. The next figure shows the situation after adjusting the PEPFAR resources in line with Government cost norms. 21 Figure 2: Showing PEPFAR funding adjusted to remove excess overhead costs (US$) 8. This now shows that when the PEPFAR contribution is scaled to fit the Government’s own cost projection, there is a much larger funding gap. There is already a gap in 2013, and then a bigger gap starts to open up from 2015. However, if the Global Fund is open to considering further funding applications from Vietnam after completion of Round 9 in 2015, the remaining gap could potentially be filled right up to 2020. It is also likely that through efficiency savings, it may be possible for Vietnam to run an effective HIV and AIDS programme at a cost somewhat below the current projection. However, this is crucially dependent on 22 there being no interruption in the prevention programme. Any loss of momentum on prevention will lead to greatly increased treatment and care costs in subsequent years. 9. These projections are based on the latest estimates by donors (including an update by PEPFAR this week). The central Government funding projection is based on the current commitment to increase funding by 20% per annum up until 2020, reiterated publicly by the Vice Minister of Health this week. The provincial Government funding is also calculated on the basis of 20% annual growth. In actual fact, provincial financing has been increasing faster than this in recent years, and Vietnam is following a path of increasing fiscal decentralization. So these projections may in fact be on the low side. 10. It is clear from this projection, which is the most accurate scenario based on currently available information, that although GoV funding is increasing slowly, it is on track to provide more funding than all the donors together as early as 2015 or 2016. By 2020 it will be funding 61% of the estimated need from domestic public finances. 11. The next figure (see Figure 3, next page) adds in the proposed DFID/WB extension. This effectively fills the gap in 2013. This may look like a small gap in financial terms, but it is critically important for two reasons: (1) the DFID money is funding crucial prevention activities for which no other provision has been made other than the extension of the Global Fund Round 9 into its Phase 2; (2) the Global Fund Secretariat in Geneva has already communicated that there will most likely be a gap of about 6 months from the Board decision in January 2013 to the actual availability of Phase 2 funds for the programme in Vietnam. 12. This is a manageable scenario. Adequate funding is assured to 2015; prevention programmes do not get interrupted; and Vietnam can apply for more Global Fund financing to bridge the gap from 2015 to 2020. 23 Figure 3: Showing adjusted PEPFAR budget with DFID 1-year extension. (US$) 13. It is of course impossible to know whether the Global Fund Board will approve the Phase 2 at its meeting in January 2013. But the approval of the DFID extension will improve the likelihood of a positive outcome. Throughout the planning process for the Phase 2, the DFID/WB teams and the DFID-funded WHO experts have been working intensely with the Global Fund’s principal recipient (a sister unit within the Vietnam Authority for HIV/AIDS Control) and the Vietnam CCM to ensure a well-planned, seamless and responsible handover of key prevention activities from DFID/WB financing to Global Fund financing. Originally, when the Global Fund Round 9 grant was approved, this transition was planned for 2012. Due to factors beyond the control of 24 the DFID/WB funded project, this could not happen. However, now that the Global Fund resources have become more constrained and subject to more conditions, and now that the Government has recognised the extreme urgency of using all resources in an integrated, cost-effective way, the conditions are right for a smooth transition in 2013. The Global Fund’s Fund Portfolio Manager for Vietnam has told the Vietnamese Government that a well-planned and epidemiologically sound handover of DFID/WB-funded prevention work to the Global Fund programme is a requirement for further grant approval. It is well recognized by all that if the prevention work currently funded by DFID/WB stops, Vietnam’s entire HIV and AIDS programme will suffer a major setback. The following figure shows the funding scenario without either the DFID or Global Fund extensions. Figure 4: Showing adjusted PEPFAR budget but without DFID or GF extensions 25 14. In this scenario, a large funding gap opens up from 2013, and without the possibility of Global Fund finance, there are no other options for filling the gap. The next applications for new Global Fund finance will not be submitted until 2015. By that time the prevention programmes will have come to a halt, with GoV having to prioritize its limited resources into care and treatment. The epidemic will almost certainly flare up out of control, setting Vietnam back by at least 5 years. 15. Another important consideration is that if the DFID/WB project is extended through 2013, this enables GoV to learn important lessons from the transition process. A well-managed transition, supported by DFID-funded WHO technical assistance, will set the standard for an even bigger transition from the Global Fund financed programme to the domestically funded National Targeted Programme in the coming years. Abrupt DFID exit in 2012 without this well-managed transition would not provide any opportunities of this nature. 16. The most positive scenario, which is not improbable, is that (1) the DFID extension provides the necessary transition in 2013; the Global Fund Round 9 Phase 2 is approved, with funding filling the gap from the second half of 2013 through to the end of 2015; and (3) Vietnam secures new financing from the Global Fund from 2015 to 2010 at approximately the same level as the current Round 9. Under this scenario, there is no funding gap until 2020, and by that time it is expected that efficiency savings will have brought down the estimated need somewhat. See the final figure below: 26 Figure 5: Showing adjusted PEPFAR budget with DFID 1-year extension and additional GF financing from 2015. (US$) 27 Annex 2 Light touch economic appraisal for the HIV/AIDS Prevention Programme extension, August 2012 Background DFID and the World Bank in Vietnam have been supporting an HIV/AIDS Prevention Programme since 2009, focusing on harm reduction activities, training and advocacy, and monitoring and evaluation. This work has been effective, contributing to Vietnam seeing the number of new HIV infections in decline for the last four years. The programme was planned to end in December 2012. However Vietnam is now subject to serious financing constraints given unexpected rapid loss of donor resources (e.g the Global Fund, and the US Government’s PEPFAR programme), and Vietnam’s own budgetary difficulties. DFID is proposing to continue its support for an additional 12 months to provide bridging funding before additional funding from the Global Fund and Government’s budget comes. This will help ensure the continuation of key prevention activities and advocacy work to bring about sustainability of the approach before we can confidently and successfully complete the programme. Methodology and assumptions This light touch economic appraisal draws heavily from the substantial economic appraisal piece of HIV/AIDS prevention programmes in Vietnam, performed by Access Economics, the University of Melbourne in March 2009. This study looked at the lifetime cost of illness per case of HIV/AIDS in people who inject drugs - the most prominent high risk behaviours, and the cost-effectiveness of prevention interventions for this group in Vietnam. It concluded that a prevention programme of £18 million would have very strong value for money with net benefits to DFID (avoided health care costs) ranging from £26 million to £59 million. The societal benefits (including also avoided lost productivity, quality of life and mortality) would range from £1.86 billion to £4.39 billion. For this analysis of the programme continuation, we use the same various figures calculated in the previous study for the following reasons, some of which will be elaborated in the Benefits section below: The Access Economics study used a standardised approach for estimating the costs and effectiveness of prevention interventions; Key parameters still hold such as the epidemiological, political, social, and institutional contexts. Vietnam is still at the low-level and concentrated epidemics stage and other contextual issues are still valid; Costs of HIV infection could have increased given the rising health care costs and productivity. However the same costs used mean that we adopt a conservative approach to estimating the expected benefits (i.e. avoided costs) Intervention cost per case prevented is assumed to be the same, and was quickly cross-checked with newly available results of cases prevented and corresponding estimated programme spending. 28 The business case considers three options in addition to the “do nothing” option. It concludes that the preferred option is extending the current programme, using the existing management and implementation mechanisms, but with tailored activities for maximum impact and sustainability. The cost and benefit analysis below presents results for this option and the counterfactual of doing nothing. Costs The programme cost for DFID is £6.2 million. This amount is proposed to be transferred to the World Bank, the implementing agency in two instalments, £4.5 million and £1.7 million in 2012/2013 and 2013/2014. For simplicity we assume that this cost will be incurred in the calendar year of 2013. Also for simplicity we do not take into account the staff cost involved with the extension, which is very small proportionately to the programme cost. The activities and their cost breakdown are as follows: Activity Harm reduction for people who inject drugs Condom social marketing Work among men who have sex with men National monitoring and evaluation system Training and advocacy Programme management DFID-managed consultancy support Allocation (£) 1,240,000 2,052,000 437,000 282,000 1,142,000 797,000 250,000 The cost of the “do nothing” option for DFID is zero. Benefits We calculate only the benefits arising from infection cases averted due to harm reduction for people who inject drugs, using the parameters identified in the Access Economics study such as intervention cost per case prevented and cost per case of HIV infection. Benefits from other prevention types such as condom social marketing or work among men who have sex with men cannot be robustly identified due to very limited evidence of cost-effectiveness in these areas. A review of value for money in HIV prevention, by the DFID supported Human Development Resource Center, found only one study related to condom distribution, out of over 30 studies reviewed. On the other hand one may well argue that a mixture of interventions is required to break the infection circle, although evidence of cost effectiveness of a comprehensive package of activities is also limited. The intervention cost per case prevented is the average of the costs in large urban city, rural province, and urban township settings, where DFID work, which is £742. This figure tally broadly with newly established data in the “Evaluation of epidemiological impacts of HIV harm reduction programmes in Vietnam”, 2011 of over 1500 cases being averted annually, and the corresponding spending. The cost per case of HIV infection, or the benefits/avoided cost per case averted, consists of health care cost, productivity loss of people with HIV/AIDS. These figures are £2,046 29 and £5,507. The benefits/avoided costs to the society, apart from the above items, include loss of wellbeing, quality of life and premature mortality. This figure is £148,574 per case. Balance of costs and benefits The below table summarises the balance of costs and benefits of the proposed project extension. Summary of costs and benefits (£) 2013 Present Value 6,200,000 5,636,364 12,616,596.32 11,469,633.02 Costs to DFID Benefits to DFID (Avoided health care costs & productivity loss) Benefits to society 248,179,290.53 225,617,536.84 (Avoided health care costs, productivity loss of HIV people and carers, quality of life and premature mortality) Net benefit to DFID Net benefit to the society 6,416,596.32 241,979,290.53 5,833,269.38 219,981,173.20 Taking into account the avoided costs in health care and productivity loss, the net benefit is significant at £5.8 million in present value, for this DFID investment of £6.2 million (or £5.6 million in present value). The societal net benefit is huge at £220 million in present value. With the “do nothing” option, the benefits would be negative, i.e unrealised benefits because of lack of support. Value for money measures The main cost-effectiveness measures for HIV prevention interventions are intervention cost per infection averted or quality adjusted life-years (DALY) saved. We will include vfm dimensions in the coming independent impact assessment. We will verify the intervention cost per infection averted used for this analysis, which is £742. This is currently in the range for low-level and concentrated epidemics of $374 - $45,173 identified in the Human Development Resource Center review mentioned above. We will also explore measuring cost per DALY saved. There are other, lower level indicators such as cost per client contact or cost per condom/syringe distributed, which can also be looked at. 30