Use of behaviour modifying collars FINAL

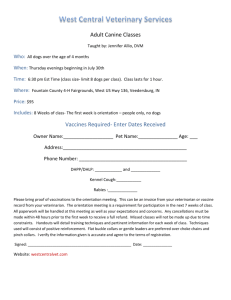

advertisement

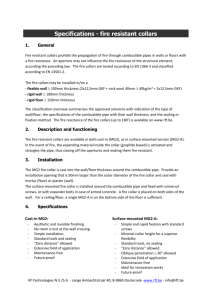

Use of behaviour-modifying collars Member comments have been incorporated to extend the policy beyond dogs and list the states where shock collars are banned. Minor editorial changes have been Policy Behaviour-modifying collars that use electric shock should not be used on animals and should be banned. Behaviour-modifying collars that use citronella (or other nontoxic substances) are not recommended. Background The use of positive reinforcement training methods is recommended for modifying the behaviour of animals. Negative reinforcement and positive punishment methods are not recommended. Although equipment based on these methods is available for use in Australia, its use is not recommended. Barking is a normal behaviour of all dogs and occurs for a number of reasons e.g. guarding, excitement, attention seeking, and anxiety. The use of punishment to control excessive barking does not take into account why the behaviour is occurring and therefore does not address the root of the problem. Dogs also escape for a number of reasons but a common reason is anxiety e.g. separation anxiety, noise fears and phobias. Punishing a dog with an anxiety disorder is inhumane. There are three different designs of behaviour-modifying collars: 1) Manual, radio controlled collars which are activated by a remote hand held transmitter. 2) Anti-bark collars which are activated when the dog barks. Such collars may utilise a microphone, a vibration sensor, or a combination of both. 3) “Invisible fence” containment devices, in which proximity to a wire placed around the boundary activates the collar. These devices often incorporate a warning” beep” which precedes the electric shock by several seconds and enables to dog to move further from the boundary wire and avoid the shock.19. Such collars – commonly called “e-collars” – may deliver an electric shock (“impulse”) a squirt of an unpleasant odour (citronella, lemon juice), a puff of air, or an ultrasonic tone. The main concern with the use of these products has been regarding e-collars. The full effects of citronella and other collars on dogs are not known however citronella and high-pitched sounds are likely to be aversive. The shocks caused by e-collars “are not only unpleasant but also painful and frightening” and cause both short-term and long-term stress.24 Risks associated with use of behaviourmodifying collars that use electric shock include the potential for dogs to develop conditions such as learned helplessness, increased anxiety, increased aggression, redirected aggression, long-term potentiation (i.e. the problem becomes worse) and reduced motivation. Positive reinforcement reward-based training has been shown to be more effective than punishment 9 when conducted by experienced professional trainers and in the hands of the general public.10,22 The use of punishment is associated with an increase in the number of problematic behaviours10 and a reduction in owner satisfaction with the dog’s general and on-leash behaviour. 12 The use of operator-controlled behaviour-modifying collars is more open to potential abuse than collars that are activated by the dog’s behaviour. Punishments (shocks) which are inappropriately applied and which the dog cannot predict (or avoid) cause more stress and suffering 12, and this is likely to be the case in the hands of an inexperienced trainer. While the AVA does not condone their use, they are in use in Australia and therefore their use must be supervised by appropriately trained registered veterinarians or a person with appropriate qualifications, training and experience in animal behaviour. They should be used in combination with other therapies that may address the underlying motivation for the behaviour including behavioural modification and medication where appropriate. The animal’s progress should be regularly reviewed and the program adjusted accordingly. The use of electric shock collars is under review in some states and territories and prohibited in others as it is in many other countries. Using shock collars on animals is currently illegal in New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia. Guidelines Those who wish to use these products should thoroughly investigate all other humane efforts to modify and manage the behaviour before electing to use this equipment. The following guidelines should be observed for the use of citronella collars on dogs: Citronella antibarking and boundary collars should only be used according to accepted principles of behavioural modification that optimise the effects of the adverse experience with the minimum of exposure. If, in the view of the supervising, competent person, the subject dog is likely to be distressed by exposure to the stimulus, then the collar should not be used. The supervising person(s) must ensure that they and the persons using the citronella collar under their supervision fully understand the principles of learning (including negative reinforcement and positive punishment) that underlie the effective use of the collars and that the collars are used properly. Veterinarians should keep records of all animals on which such products are used. They should be used in combination with other therapies that may address the underlying motivation for the behaviour including behavioural modification and medication where appropriate. The animal’s progress should be regularly reviewed and the program adjusted accordingly. Citronella antibarking collars A citronella antibarking collar must only be activated by the behaviour of the dog that is to be controlled. The device should not be activated by other influences, such as the behaviour of other animals, extraneous noise or electronic interference. o The initial use of a citronella antibarking collar should be under direct supervision of a competent person who has been instructed and trained in the use of the collar until that person is satisfied that the device is operating correctly and without causing undue distress to the dog. Citronella boundary collars Boundary collars must contain a mechanism that gives the dog an initial audible or visual warning (e.g. a marker tape). The dog must only experience the aversive stimulation if it ignores the warning and continues to approach a boundary. If the dog immediately ceases that behaviour, then it must not experience the stimulus. Other recommendations The AVA believes there should be an Australian Standard for behaviour-modifying collars. Other relevant policies and position statements 6.1 Companion animal welfare and responsible pet ownership 6.14 Obedience training References and further reading 1. Azrin NH et al (1967). Attack, avoidance and escape reactions to aversive shock. Journal of Exp Animal Behaviour 10:131–148. 2. Beerda B, Schilder MBH, van Hoof JARAM, de Vries HW and Mol JA 1998 “Behavioural, saliva cortisol and heart rate responses to different stimuli in dogs” Applied Animal Behaviour Science 58: 365-381 3. Blackwell E and Casey R 2006 “The use of shock collars and their impact on the welfare of dogs” a review for RSPCA UK available at http://www.rspca.org.uk/servlet/Satellite?blobcol=urlblob&blobheader=application/pdf&blobk ey=id&blobtable=RSPCABlob&blobwhere=1138718966544&ssbinary=true 4. Blackwell EJ, Twells C, Seawright A and Casey RA 2008 “The relationships between training methods and the occurrence of behaviour problems, as reported by owners, in a population of domestic dogs” Journal of Veterinary Behaviour 3: 207-217 5. Blackwell, EJ, Bolster C, Richards G, Loftus BA and Casey RA 2012 “The use of electronic collars for training dogs: estimated prevalence, reasons and risk factors for use, and owner perceived success as compared to other training methods” BMC Veterinary Research 8:93 6. Coleman T and Murray RW 2000 “Collar mounted electronic devices for behaviour modification in dogs” Proceedings of the 9th National Urban Animal Management Conference, Hobart, Australian Veterinary Association. 7. Cooper J, Wright H, Mills DE, Casey R, Blackwell E, van Drel K and Lines J 2010 “Studies to assess the effect of pet training aids, specifically remote static pulse systems, on the welfare of domestic dogs” Defra AW1402 available at http://randd.defra.gov.uk.Documents.aspx?Document=1167_AW11402SIDSFinalReport.pdf 8. Cooper J, Wright H, Mills DE, Casey R, Blackwell E, van Drel K and Lines J 2011 “Studies to assess the effect of pet training aids, specifically remote static pulse systems, on the welfare of domestic dogs” Defra AW1402a available at http://randd.defra.gov.uk.Documents.aspx?Document=1168_AW11402aSIDSFinalReport.pd f 9. Haverbeke, A., Laporte, B., Depiereux, E., Giffroy, J-M., Diedrich, C. 2008. Training methods of military dog handlers and effects on their team's performances Applied Animal Behaviour Science 113: 110-122 10. Hiby EF, Rooney NJ and Bradshaw JWS 2004 “Dog training methods: their use, effectiveness and interactions with behaviour and welfare” Animal Welfare 13: 63-69 11. Juarbe-Diaz S and Houpt KA (1996). Comparison of two antibarking collars for treatment of nuisance barking. Journal of American Animal Hospital Association 32:231–235. 12. Kwan JY and Bain MJ 2013 “Owner Attachment and Problem Behaviors Related to Relinquishment and Training Techniques of Dogs” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 16 (2) 168-183 (DOI:10.1080/10888705.2013.768923) 13. Lines JA, van Driel K and Cooper JJ 2013a “The characteristics of electronic training collars for dogs” Veterinary Record Vol 172: 288 (doi: 10.1136/vr.101144) 14. Lines JA, van Driel K and Cooper JJ 2013b (Letter) Veterinary Record 172: 243 (doi: 10.1136/vr.f1333) 15. Mills DS, Lord Soulsby, McBride A, Lamb D, Morton D and Wesley S (2012) “The Use of Electric Pulse Training Aids (EPTAs) in Companion Animals” Report for the Companion Animal Welfare Council, June 2012 www.cawc.org.uk 16. Overall KL 2007a “Why electric shock is not behaviour modification” Journal of Veterinary Behaviour 2: 1-4 (editorial) 17. Overall KL 2007b “Considerations for shock and training collars: Concerns from and for the working dog community “ Journal of Veterinary Behaviour 2: 103-107 (editorial) 18. Perkins 2003 (letter) Australian Veterinary journal 81 (1,2) 19. Polsky R (1994). Electronic shock collars: are they worth the risks? Journal of American Animal Hospital Association 30:463–468. 20. Polsky R (2000). Can aggression in dogs be elicited through the use of electronic pet containment systems? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare 3(4):345–357. 21. Riepl M 2013 (letter) “Characteristics of electronic training collars for dogs” Veterinary Record 172: 242-243 (doi: 10.1136/vr.f1332) 22. Rooney NJ and Cowan S (2011) Training methods and owner–dog interactions: Links with dog behaviour and learning ability. Applied Animal behaviour Science 132: 169 – 177. 23. Schalke E, Stichnoth J, Ott S and Jones-Baade R 2007 "Clinical signs caused by the use of electric training collars on dogs in everyday life situations" Applied Animal Behaviour Science 105: 369-380 24. Schilder MBH and van der Borg JAM (2004). Training dogs with help of the shock collar: short and long term behavioural effects. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 85:319–334. 25. Schultz RN, Jonas KW, Skuldt LH, and Wydeven AP 2005 “Experimental use of dogtraining shock collars to deter depredation by gray wolves” Wildlife Society Bulletin 33: 142148 26. Steiss JE, Schaffer C, Ahmad H and Voith VL 2007 “Evaluation of plasma cortisol levels and behavior in dogs wearing bark control collars” Applied Animal Behaviour Science 106: 96-106