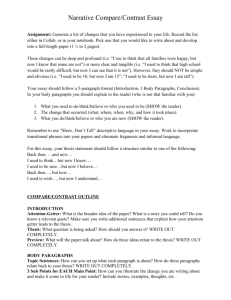

BASIC OUTLINE of your rhetorical analysis essay

advertisement

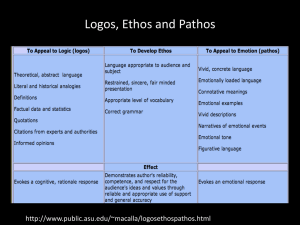

L. May, English 101 (Winter 2010) BASIC OUTLINE of your rhetorical analysis essay INTRODUCTION (1-3 paragraphs). Include the follow elements in your introduction section (not necessarily in this order). - GET STRAIGHT TO THE POINT. Introduce your reader (me and your classmates) to the piece you’ll be analyzing. (Yes, we already know about it. But pretend we’ve forgotten . ) You don’t have to provide much by the way of a “hook” to get the reader interested. Assume the reader would not have picked up your essay had she/he not been interested in reading an analysis of the piece in question already. So you can jump right in by immediately introducing the writer to the piece itself. For example, you could start with, “In “A case for faith,” an op-ed piece for The Tufts Daily, the student newspaper of Tufts University, student Sharon Neely argues that religious faith is as valid as scientific “faith.”” - STATE WRITER’S MAIN POINT (THESIS) AND REASONS. State the writer’s one main point (thesis), if you haven’t already: “In “Imagine No Heaven,” Salman Rushdie argues that religion provides no benefits at all to society. In fact, he confidently asserts that all religion has a negative effect on society because ______________, _______________, and ___________” - SUMMARIZE. Summarize the supporting reasons and evidence the writer provides. See They Say, I Say, chapter 2, “The Art of Summarizing.” - PROVIDE NEEDED BACKGROUND INFORMATION. Provide the reader any background information needed on the issue at hand. For example, if you were writing about “God Diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder,” you’d want to make sure your reader understood that this piece was published in a magazine known for its humorous and satirical pieces. Basically, give your reader some basic background information on your writer (not just any information, but information which helps the reader understand your analysis) and on the circumstances of the piece’s publication (for instance, where – in what publication – was it published, what type of piece it is (an opinion piece, a humorous piece)). - STATE YOUR MAIN POINT (THESIS) AND REASONS. Include an explicit statement of what you are arguing, what your claim about the rhetorical effectiveness / ineffectiveness of this piece is. For example, “While Sharon Neely’s piece may be somewhat effective on people who already agree with her, due to its many logical fallacies, this piece would likely be completely ineffective on readers who doubted the validity of religious faith.” Here the thesis is basically “Neely’s piece is ineffective on readers who don’t already believe in the validity of religious faith.” And the reason is “due to its many logical fallacies.” BODY (2-3 pages). Include these analytical “moves’ in this section. - FOCUS ON PROVING YOUR SPECIFIC THESIS. Your thesis statement should have zeroed in one to three significant ways in which this writer effectively (or ineffectively) achieves her purpose with her/his audience(s). Now provide your reader with a detailed and coherent analysis and explanation of exactly how this piece is effective or ineffective for this audience. L. May, English 101 (Winter 2010) - ANALYZE THE PIECE IN DETAIL. DON’T JUST IDENTIFY RHETORICAL ELEMENTS. Here is where you’ll want to follow the “formula for rhetorical analysis” (on a handout I handed out last week). a. Make a claim/assertion that supports your main claim (aka “main point,” “thesis). b. Identify an example (or more) that supports this claim. c. Re-state / interpret the example in your own words d. Explain how this example works to support your thesis. a. CLAIM: “Rushdie’s use of pathos is especially evident in his vivid word choice. This word choice would likely effectively persuade even some agnostics and religious believers in his audience. b. IDENTIFY AN EXAMPLE: For instance, in one of his most powerful lines, he boldly asserts that one’s religion “may at some point come to feel inescapable, not in the way that the truth is inescapable, but in the way that jail is” (paragraph 6). c. RE-STATE / INTERPRET THE EXAMPLE IN YOUR OWN WORDS: Certainly, no one, not even the most devout religious believer would want to live in a jail. d. EXPLAIN HOW THIS EXAMPLE WORKS TO SUPPORT YOUR THESIS: Also by using the word “jail,” he is showing the reader not just telling them. In other words, he could have simply said, “Religion will limit you your entire life.” But that would just be telling his reader, and thus not making much of an impression on them on the level of values and emotion (pathos). By picking a word like “jail,” on the other hand, he picks a word every reader can visualize and vividly imagine, whether they’ve ever actually been in a jail or not. - CREATE A “QUOTATION SANDWICH” EACH TIME YOU INCLUDE A QUOTATION IN YOUR ESSAY. See Chapter 3, “The Art of Quoting,” in They Say, I Say. In this way, your quotations are smoothly integrated into your essay and make your essay a lot easier to understand. - SET UP AND DOCUMENT YOUR QUOTATIONS PER MLA FORMAT. See TSIS Chapter 3 as well as Hacker “MLA-3” (362-369) CONCLUSION (likely only one paragraph, but it could well be two) - STICK TO RHETORICAL ANALYSIS. DON’T COMMENT ON THE QUESTION AT HAND. In your conclusion, remember to stick with a summary or reflection on what your analysis revealed about the piece. In other words, DO NOT get “off topic” by slipping into a commentary on the issues at hand. Don’t say something like, “Even though Rushdie doesn’t believe that religion is valuable, it actually very much is.” That would be switching your topic from a rhetorical analysis to an argument about the topic of religion itself. - SUMMARIZING IS FINE. Basically, simply summarize in fresh words (not, in other words, the same phrases and words you used in the body) what your analysis revealed: the piece’s effectiveness/ineffectiveness for a particular audience, and how it was especially effective / ineffective. - YOU COULD REFLECT ON WHAT YOU”VE LEARNED ABOUT THE POWER OF RHETORICAL APPEALS (logos, ethos, pathos). If you wanted to get creative (which I would love to read), you could comment on the particular strategy the writer used. For example, if you emphasize the way in which a writer uses pathos, you could reflect on the way in which writing that appeals to readers’ emotions and values is often so powerful.