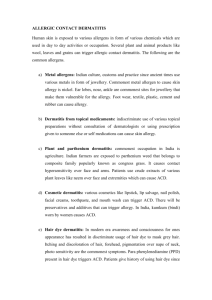

Factors contributing to the development of occupational contact

advertisement