narrative structure

advertisement

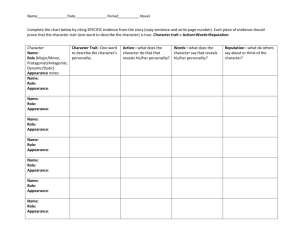

Narrative Structure The story (all the events in the story arranged in chronological order, as they “happened”) The Plot (the structure given to the narrative by the author, the way the story is actually presented to the reader). Plots may be episodic: events are held together mainly by the fact that they happen to the protagonist unified: events are carefully organized to create the effect of unity of action, constituting one action with a continuous sequence of beginning, middle, and end. polyphonic: main plot is interwoven with one or more subplots that enhance its meaning Point of View: the way a story is told; the perspectives which are presented to the reader First-Person Narrative: the narrator refers to him/herself with the pronouns “I” and “me” Protagonist or Participant/Observer self-consciously narrating or Unself-consciously narrating Reliable or Unreliable/Fallible Third-Person Narrative: the story is told in the third-person, with pronouns “I” and “me” used only in dialogue Omniscient: narrator knows everything about all characters, events, etc.; omniscient narrators may also occasionally employ embedded focalisers, characters whose perspectives temporarily control the narrative Intrusive: narrator comments on and evaluates characters and actions; establishes what counts as facts and values in the narrative Unintrusive /Impersonal/Objective: narrator “shows rather than tells”; does not explicitly comment on or evaluate the actions Limited Point of View: narrative is controlled through the limited perspectives of one main character (or a very few important characters) who does not know everything; such a third- person focaliser is often called a centre of consciousness Gustav Freytag’s1 analysis of dramatic structure, based on five-act plays: Die Technik des Drama, 18632 The exposition provides the background information needed to properly understand the story, such as the protagonist, the antagonist, the basic conflict, and the setting. (A specific exposition stage is criticized by Lajos Egri in The Art of Dramatic Writing. He states, “exposition itself is part of the whole play, and not simply a fixture to be used at the beginning and then discarded.” According to Egri, the actions of a character reveal who they are, and exposition should come about naturally. The beginning of the play should therefore begin with the initial conflict.) 1 German playwright and novelist Freytag’s analysis was intended to apply not to modern drama, but rather to ancient Greek and Shakespearean drama. 2 The exposition ends with the inciting moment, which is the incident without which there would be no story. The inciting moment sets the remainder of the story in motion beginning with the second act, the rising action. During rising action, the basic internal conflict is complicated by the introduction of related secondary conflicts, including various obstacles that frustrate the protagonist’s attempt to reach his/her goal. Secondary conflicts can include adversaries of lesser importance than the story’s antagonist, who may work with the antagonist or separately, by and for themselves or actions unknown. The third act is that of the climax, or turning point, which marks a change, for the better or the worse, in the protagonist’s affairs. If the story is a comedy, things will have gone badly for the protagonist up to this point; now things will begin to go well for him or her. If the story is a tragedy, the opposite state of affairs will ensue, with things going from good to bad for the protagonist. During the falling action, or resolution, which is the moment of reversal after the climax, the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist unravels, with the protagonist winning or losing against the antagonist. The falling action might contain a moment of final suspense, during which the final outcome of the conflict is in doubt. (Contemporary dramas increasingly use the fall to increase the relative height of the climax and dramatic impact (melodrama). The protagonist reaches up but falls and succumbs to their doubts, fears, and limitations. Arguably, the negative climax occurs when they have an epiphany and encounters their greatest fear or loses something important. This loss gives them the courage to take on another obstacle. This confrontation becomes the classic climax.) A comedy ends with a dénouement (a conclusion) in which the protagonist is better off than at the story’s outset. In literature, a dénouement consists of a series of events that follow the climax of a drama or narrative, and thus serves as the conclusion of the story. Conflicts are resolved, creating normality for the characters and a sense of catharsis, or release of tension and anxiety, for the reader. Etymologically, the French word dénouement is derived from the Old French word denoer, "to untie", and from nodus, Latin for "knot." Simply put, dénouement is the unraveling or untying of the complexities of a plot. A tragedy ends with a catastrophe in which the protagonist is worse off than at the beginning of the narrative. The catastrophe is the final resolution, which unravels the intrigue and brings the piece to a close, it may involve the death of one or more main characters. It is the final part of a play. Conflict Character vs. Self is when the central conflict of a story is internal to the main character, and is often portrayed as a conflict between the characters. Otherwise described as an internal conflict in which a character struggles with himself (a desire, or moral dilemma). Character vs. Character is when there is a conflict of two forms of like beings. An example is the hero's conflicts with the central villain of a work. There are usually several arguments/disagreements before the climax is reached. Character vs. Society is a theme in fiction in which a main character's, or group of main characters', main source of conflict is social traditions or concepts. In this sense, the two parties are: a) the protagonist(s) and b) the society of which the protagonist(s) are included. Society itself is often looked at as a single character, just as an opposing party would be looked at in a Character vs. Character conflict. Character vs. Nature is the theme in literature that places a character against forces of nature. Character vs. a spirit. This could be ghosts, monsters, demons, etc. Character vs. Destiny is a theme where one attempts to break free of a predetermined path chosen before him prior to his knowledge. If can also be referred to as an issue between fate and freewill. A common example is Shakespeare's Macbeth. As with other literary terms, these have come about gradually as descriptions of common narrative structures. Conflict was first described in ancient Greek literature as the agon, or central contest in tragedy. According to Aristotle, in order to hold the interest, the hero must have a single conflict. The agon, or act of conflict, involves the protagonist (the "first fighter") and the antagonist (a more recent term), corresponding to the hero and villain. The outcome of the contest cannot be known in advance, and, according to later critics such as Plutarch, the hero's struggle should be ennobling. Even in contemporary, non-dramatic literature, critics have observed that the agon is the central unit of the plot. The easier it is for the protagonist to triumph, the less value there is in the drama. In internal and external conflict alike, the antagonist must act upon the protagonist and must seem at first to overmatch him or her In many non-fictional narrative genres, even though the author lacks the same freedom to control the action and plot, selection of subject matter, degree of detail, and emphasis permit an author to create similar structures. An anti-climax is where something which would appear to be difficult to solve in a plot is solved through something trivial. The term anti-climax is also used when the falling action portion of a story is criticized for lasting too long and diminishes the impact of the climax. In a narrative, motifs are recurring structures, contrasts, or literary devices that can help to develop and inform the piece’s major themes. The narrative motif is the vehicle by means of which the narrative theme is conveyed. The motif can be an idea, an object, a place or a statement. The flute in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman is a recurrent motif that conveys rural and idyllic notions. The green light in The Great Gatsby and the repeated statement, "My father said that the reason for living is getting ready to stay dead." A motif can be something that recurs to develop the theme in a novel. A motif can also be used to connect different scenes or points in time. A motif differs from a theme in that a theme is an idea set forth by a text, where a motif is a recurring element which symbolizes that idea. Most narratives have a protagonist (one primary character who is the main focus of interest), who may or may not have an antagonist (one main opponent) and/or a foil (one or more figures who highlight the protagonist by their contrast with him/her). Freytag’s Pyramid: