HY 7510 Historiographical Paper 1

advertisement

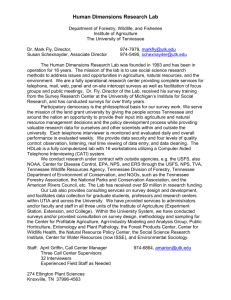

Tucker 0 Kimberly Tucker HIST 7510: Historiographical Paper Dr. Conard 10/15/2010 Historiographical Essay: New Freedoms for Southern African Americans that Emerge Through the New Agricultural Labor System Tucker 1 The study of the Civil War, especially the impact of the Civil War on the national and local landscapes and in the lives of Americans, has a long historiographical tradition. Within this historiography lay several important twentieth century historians who have examined the aftermath of the Civil War through the lenses of economic, legal, social, and cultural change. In fact, Heather Cox Richardson states that “the emancipation of southern slaves had inaugurated a new era of human freedom in America.” Stephen Ash, Donald Winters, Robert McKenzie, Paul Phillips, Paul Cimbala, John Lodl, and Thomas Brown all contribute to this Civil War historiography by focusing on the new freedoms and agency that southern African Americans gain in the economic realm through the transition from the old plantation labor system of slavery to the new agricultural labor system of sharecropping. The scope of their studies encompasses both the national landscape and the regional setting of Middle Tennessee. Each author also approaches this topic from different perspectives and with different interpretations. Still, by focusing on each historian’s argument and methodology, the historiography concerning the new era of freedom that emerges for African Americans through sharecropping can be better understood. Historian Stephen Ash is one of the few scholars who traces southern societal changes brought about by the Civil War in the groundbreaking and most recent historiographical work discussed in this essay, Middle Tennessee Society Transformed, 1860-1870. Through his investigation of the Civil War’s impact on the thirteen counties of Middle Tennessee, Ash presents the arguments that “Middle Tennessee on the eve of the Civil War represented a ‘third South’ and that emancipation unleashed forces that transformed the region’s society from a biracial one to a dual one divided by race.”1 Within his arguments, Ash concentrates on the 1 Stephen V. Ash. Middle Tennessee Society Transformed, 1860-1870: War and Peace in the Upper South (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2006), xviii. Tucker 2 importance of emancipation for African Americans’ economic freedom. He explains that in the postbellum years there were rural labor shortages because blacks continued their exodus from farms and plantations. This lack of labor resulted in the “shift of bargaining power in favor of the laborers, white and black alike.”2 As blacks realized their negotiating power, they were able to demand shorter work days and easier work, quit gang work, and secure “small tenant farms to cultivate on their own, paying the owner in cash or, more often, crop shares.”3 Even though this sharecropping system – “in conjunction with the credit monopolies of local merchants, a pernicious crop-lien system, and state laws limiting tenants’ rights and freedom – entangled sharecroppers in a web of poverty and dependence,” it also provided a “true liberation for the agrarian working class, providing many of the landless with some measure of control over their own livelihoods and a significant degree of independence from the landowners.”4 Ash justifies his claim that Middle Tennessee holds the status of a “third South” by explaining that this region lies between the plantation society and the yeoman society because the farmers dominated the agricultural wealth while the aristocrats controlled the political offices and social hierarchy, and the agricultural economy was more diversified, as it was mainly based on corn and livestock production and agricultural exportations. However, the war destroyed Middle Tennessee’s economy and the end of the war saw the emergence of a new labor system, as well as the economic and social reestablishment of the aristocracy and the willingness of the lower-class whites to accept their authority. Still, the postwar years for the region’s agrarian folk were not completely dire. In fact, both African American and white farmers gained new opportunities in education and improvement through the “many prewar agricultural societies and 2 Ibid., 187. Ibid., 187. 4 Ibid., 187. 3 Tucker 3 fairs [that were] revived after the war and new ones [that] sprang up across the region.”5 The new labor system, known as sharecropping, also meant new economic freedoms and different working conditions for freedmen because “economic reality, Federal injunctions, and the resolute determination of the freedmen soon compelled even the most obstinate white to capitulate and commence paying his black farmhands and servants with wages or crop shares.”6 Ash also argues for the evolution of a society divided by race after emancipation. He claims that it was only after emancipation that African Americans were able to achieve freedom and control their own destiny because it was then that “slaves realized that their masters no longer held the power of compulsion over them, that is when they understood that they could leave without fear of recapture or could refuse orders and resist punishment without fear of ultimate retribution.”7 Ash explains that, before the war, Middle Tennessee was a biracial society in which African Americans and whites were not integrated but intertwined. Essentially, the races were separated even though they went to church together and shared the same shopping, working, and living areas: they were separated but occupied the same spaces. However, emancipation transformed the region from this biracial society into a dual society divided by race. He illustrates that, despite “the repeated collisions of reality and illusion” in the heartland’s postwar landscape, the white Middle Tennesseans “inveterate racist and paternalistic ideology,…[as well as] their newly reinforced traditional ties,” strengthened their belief in the unworthiness of the blacks and the legitimacy of their own fossilized social system and stale ideology. The freedmen, for their part, gathered in their new homes and churches and communities, rejected the white world and its gospel of racial and class inequality, stoically endured their legal and economic subjugation, and prayed hopefully for brighter days ahead. The Civil War in Middle Tennessee – more precisely, black initiative unleashed by the war – had liberated black 5 Ibid., 189. Ibid., 139. 7 Ibid., 114. 6 Tucker 4 society and pointed it toward the future, only to immure white society and point it toward the past.8 In order to support this interpretation, inform his argument, and create a picture of Middle Tennessean society from 1860-1870, Ash employs a variety of primary sources that include census data, church records, government documents, manuscript census, private papers, county records. He provides a useful list of the sources available. However, the information obtained from those sources is spread over the years and across the counties. Thus, because his information and supporting evidence is patched together from many different data sources, he illustrates the dilemma of constructing history, not revealing history. Also, while Ash’s source base allows him to understand broad patterns, it does not provide a basis from which to probe the psyche of the people. In “Postbellum Reorganization of Southern Agriculture,” Donald L. Winters also stresses the importance and centrality of emancipation in ushering in a new era of freedom for African Americans in the postbellum South through the restructuring of plantation agriculture. However, while Ash focuses on Middle Tennessee, Winters applies his arguments to the whole state of Tennessee. Also, instead of using church records or census data as a source base, Winters employs legal and judicial documents and family histories to argue that the reorganization of labor manifested into a system known as sharecropping, which was “an acceptable compromise between landowners seeking a system of labor organization and landless farmers seeking a system of land tenure.”9 This new agricultural system offered many opportunities for both the landowners and landless farmers (both freed slaves and poor whites). When the newly freed slaves realized that the federal government would not redistribute their old masters’ land, and 8 Ibid., 252, 253. Donald L. Winters. “Postbellum Reorganization of Southern Agriculture: The Economics of Sharecropping in Tennessee.” Agricultural History 62 (1988): 1. 9 Tucker 5 that they would not gain “forty acres and a mule,” freedmen decided sharecropping would be their best alternative because it “furnished them with the use of land” for which they were responsible and allowed them “to tap the owners’ supply of capital and managerial expertise,” develop credit (through credit provisions such as crop liens), and amass a small savings.10 Freedmen’s organizations, including the Freedmen’s Bureau, provided some aid and assistance to African Americans that included giving them traction in legal and economic realms. This was important for the newly freed slaves because landownership equaled freedom. Winters argues for the institutionalization of this sharecropping system across the South after emancipation through an adjustment process that consisted of “landowners and croppers implement[ing] agreements that spelled out with increasing precision and regularity their mutual obligations and understandings; state courts handed down decisions eliminating ambiguity in the rights and legal relationship of parties to sharecropping contracts;” and state legislatures “passed laws designed to protect the interests of landowners and croppers.”11 Winters goes on to explain that one aspect of this adjustment period was the interpretation of the relationship between landowner and cropper. One interpretation put forth by historians insists that an employee – employer relationship was developed throughout the South and used the sharecropping system as a means of racial control rather than agricultural production. This relationship, in which “the planter owned the entire crop from the time it was sown and paid a portion of it after the harvest to the cropper in return for his labor,” was designed to “mobilize the labor of freedmen and to keep blacks dependent upon and subordinate to white planters.”12 As labor contracts were formed, there were initial disparities between the contracts of white croppers and black croppers that depicted this racial control. However, these disparities began to disappear and “virtually all 10 Ibid., 2. Ibid., 3. 12 Ibid., 3. 11 Tucker 6 contracts, irrespective of the cropper’s race, provided for a simple division of the crops.”13 Even the Supreme Court declared that the cropper was not legally under the employment of the landowner. Winters explains that this change in the form of contracts and the “judicial clarification of the legal relationship between the parties to those contracts,” which emphasizes the division of the crops, institutionalized the sharecropping system and created a tenants-incommon relationship between landowner and cropper, not an employer-employee relationship.14 Essentially, in postwar circumstances, sharecropping became institutionalized through contracts, judicial developments, and legislative developments. Winters also argues that it was more of a tenants-in-common relationship due to “the mutual economic dependence of the landowner and the cropper,” (in which the planter needed to sustain production on their land while the freedmen needed to support their families), “the high risks of commercial agriculture, the croppers’ credit needs, and the accumulation of human capital by blacks.”15 Like Ash and Winters, Robert Tracy McKenzie also focuses his article, “Freedmen and the Soil in Upper South,” on the transformation and reorganization of agricultural labor. These three historians also study this topic from a local perspective: Ash concentrates on the thirteen counties that compose Middle Tennessee and Winters and McKenzie broadens the setting to explore sharecropping across the state of Tennessee. In his article, McKenzie’s argument centers on his opposition to and reevaluation of the standard scenario of the social and economic reconstruction of the postbellum South. He disagrees with the standard scenario by focusing “upon two elements of the accepted account [as they apply to Tennessee]: the rapidity of institutional reorganization resulting in the clear predominance of sharecropping by 1880 and the 13 Ibid., 5. Ibid., 8. 15 Ibid., 18. 14 Tucker 7 negligible extent of black land accumulation during the same period.”16 Like Winters before him and Ash after him, McKenzie insists that emancipation forced freedmen and former masters to redefine their relationship. He lays out three competing visions for this new relationship in the postwar world. Tennessee’s former slaves envisioned a postwar world in which “a black community of freeholding farmers [were] largely independent of white interference” and the government redistributed their old master’s plantations.17 White Tennesseans wanted a future where blacks played “no role in the state’s agriculture.”18 This vision would be realized through the “colonization of the freedmen and immigration of white laborers.”19 However, most Tennesseans believed in a third vision that would “use black labor effectively” by restricting “the mobility of blacks and…fashion[ing] land and labor arrangements that resembled slavery as closely as possible.”20 While none of these visions were fully realized, McKenzie concentrates on the third vision. He argues that landowners were unable to immobilize blacks and, “for at least the first fifteen years after emancipation, Tennessee blacks moved freely throughout the countryside, utilizing their new mobility in order to reunite with family members, take advantage of economic opportunities, and resist oppression.”21 With the mobility of freedmen, which resulted in a ruralto urban shift, there was a shortage of labor that caused landowners to accede to black demands for increased independence. Essentially, in his study on the transformation of southern agriculture after emancipation, McKenzie argues that blacks were able to gain more freedom than previous historians have contended because the standard scenario they put forth Robert McKenzie. “Freedmen and the Soil in the Upper South: The Reorganization of Tennessee Agriculture, 1865-1880.” Journal of Southern History, 59 (1993): 4. 17 Ibid., 6. 18 Ibid., 7. 19 Ibid., 7. 20 Ibid., 8. 21 Ibid., 9. 16 Tucker 8 underestimated the mobility of blacks, distorted the supremacy of family-based labor arrangements among Tennessee’s freedmen, and understated the “extent to which Tennessee blacks acquired and lost land during the early postbellum period.”22 In his study on the economy and race in the post-emancipation South, “A General Remodeling of Every Thing,” Stephen West slightly resembles McKenzie in the sense that a large portion of his essay is devoted to examining over a generation of historiography that has favorably viewed C. Vann Woodward’s seminal work, Origins of the New South, 1877-1913, and agreed with his assertions about the postbellum economy: “the fall of the planter class, the emergence of sharecropping, tenancy, and the crop lien, and the rise of a new middle class.”23 He then surveys more recent developments in this historiography in order to identify further possibilities in the direction of this literature. Like McKenzie, West questions the “prevailing interpretations about the development and importance of sharecropping after the Civil War.”24 He calls for historians to rethink the prevalence of sharecropping among African Americans, the organization of black labor in the household economy, and the legal basis of free labor. He also advocates for a comparative or international approach to the study of this topic during the postemancipation years. John Rodrigue further develops West’s examinations about African Americans in the post-war South by investigating black agency after emancipation, the development of the free black community, and the creation of a free black social and cultural life. In order to illustrate that black freedom, achievement, and agency lay at the center of Reconstruction, he divides the historical scholarship into the following cultural categories: rural economy, family and gender, 22 Ibid., 17. Stephen A. West. “A General Remodeling of Every Thing: Economy and Race in the Post-Emancipation South,” in Reconstructions: New Perspectives on Postbellum America, ed. Thomas J. Brown (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 11. 24 Ibid., 22. 23 Tucker 9 urban life, education and religion, and community. Like Ash and Winters, Rodrigue concentrates on the importance of black freedom and black agency as it emerged from the transition to free labor and “contributed to the failure of Reconstruction.”25 He argues that “while scholars have emphasized different aspects of black economic aspirations or have identified varying tendencies among freedpeople in the pursuit of economic autonomy,” blacks pursued and were able to gain economic success and independence through the acquisition of property.26 In order to understand the reconstruction of the post-war South, both Paul Phillips and Paul Cimbala the creation, nature, and eventual failure of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Phillips concentrates on the localized history of the Bureau in Tennessee, while Cimbala explores the Bureau as it applies to the larger setting of the American South. Both historians discuss the organization of the Bureau, relief work and philanthropy, the contract system of free labor and abandoned or desired land, education, and opposition to the Bureau and rights of freed slaves. They also give detailed accounts of this federal agency’s activities in overseeing and assisting the newly freed blacks “in the transition from slavery to responsible freedom and citizenship.”27 John C. Rodrigue. “Black Agency after Slavery,” in Reconstructions: New Perspectives on Postbellum America, ed. Thomas J. Brown (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 44. 26 Ibid., 47. 27 Paul David Phillips. A History of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Tennessee. PhD diss. (Vanderbilt University, 1964), 1. 25 Tucker 10 Works Cited Ash, Stephen V. Middle Tennessee Society Transformed, 1860-1870: War and Peace in the Upper South. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2006. Cimbala, Paul A. The Freedmen’s Bureau: Reconstructing the American South after the Civil War. Florida: Krieger Publishing Company, 2005. McKenzie, Robert Tracy. “Freedmen and the Soil in the Upper South: The Reorganization of Tennessee Agriculture, 1865-1880.” Journal of Southern History, 59 (1993): 63-84. Phillips, Paul David. A History of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Tennessee. PhD diss., Vanderbilt University, 1964. Rodrigue, John C. “Black Agency after Slavery.” In Reconstructions: New Perspectives on Postbellum America, ed. Thomas J. Brown. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. West, Stephen A. “A General Remodeling of Every Thing: Economy and Race in the PostEmancipation South.” In Reconstructions: New Perspectives on Postbellum America, ed. Thomas J. Brown. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Winters, Donald L. “Postbellum Reorganization of Southern Agriculture: The Economics of Sharecropping in Tennessee.” Agricultural History, 62 (1988): 1-19.