Key Concepts of Argument / Persuasion

advertisement

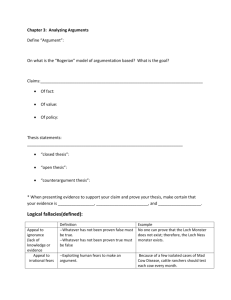

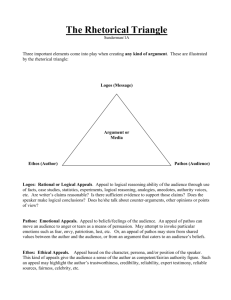

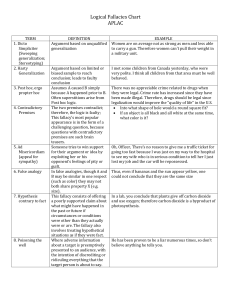

Vine/Hemer Argument/Persuasion Concepts English106 1 Key Concepts of Argument / Persuasion Argumentation: Using clear thinking and logic to convince readers of the soundness of a position or opinion. It aims to encourage acceptance of ideas. Persuasion: Using emotional language and dramatic appeals to the readers' concerns, beliefs, and values. It aims to gain readers' commitment to a course of action. In practice, the two are usually combined. Aristotle’s Three Components of Argument/ Persuasion Aristotle recognized three areas in which the writer of argument/ persuasion must appeal to an audience: Logos: Pathos: Ethos: logical appeal; employs facts, statistics, examples, authoritative statements; appeals to readers' sense of reason emotional appeal; is sensitive to the connotative power of language; appeals to readers' needs and attitudes ethical appeal; establishes writer's credibility; appeals to readers' ethics or values Ideally, the three should balance in some way. Depending on audience and purpose, the balance will be different for each writing situation, but all three elements should be included. Inductive and Deductive Reasoning Inductive Logic: is newer than deductive reasoning is a product of the scientific age is reasoning from specific examples to draw general conclusions. In the local newspaper over a period of weeks, you read news stories and police records reporting the following: Several people were mugged while shopping downtown last week. A number of homes and apartments were burglarized in the past few weeks. A growing number of cars have been stolen from people’s driveways or vandalized while parked on the street. You conclude that the local police force has been negligent about protecting the town. You have just used inductive reasoning. In the persuasive argument, induction usually takes these forms: Sampling--arriving at a conclusion about a group through reference to a certain percentage of that group Analogy--suggesting that things that are alike in some ways must also be alike in others Causal generalization--generalizing about many members of a class to determine why one member is different Flaws that may occur in inductive arguments: Too few samples (hasty generalization)—not examining the full situation before coming to a conclusion Irrelevant samples Atypical examples—cases looked at don’t represent what happens most of the time Faulty analogy—comparing two situations that aren’t essentially similar Faulty cause and effect—assuming that because something happened before something else, the first event caused the second, or assuming a causal relationship between events that are not causally connected Failure to realize that the conclusion in induction requires an "inductive leap" or inference; it is rarely an entirely sure statement Examples of Cause / Effect Fallacies: 1. 2. 3. 4. We are experiencing high unemployment, which is being caused by low consumer demand. (This may be true, but both of these may be caused by high interest rates, so a good analysis should dig deeper). Smoking is causing air pollution in Los Angeles. (Smoking may indeed be a contributing factor, but its significance is probably slight compared with other causes such as automotive and industrial pollution). The accident was caused by the poor location and overgrowth of the bushes. (This may be true, but if the driver had not been speeding and if the pedestrian had not been jaywalking, the accident might have been avoided in spite of the bushes. Examine ALL causes and emphasize the most significant). The increase in AIDS cases was caused by expanded sex education programs. (The cause & effect are reversed here). Vine/Hemer Argument/Persuasion Concepts English106 5. You have a fever, and this is causing you to break out in spots. (Identifying one effect as the cause of another, when, in fact, both are caused by another factor—in this case, chicken pox virus—is another logical flaw that can occur in cause /effect reasoning). 2 Deductive Logic: goes back to the ancient Greeks as a tool or rule for a mental game of questioning, they devised the syllogism—a formal way to set up a deductive argument the syllogism has been adapted to Boolean mathematics as well, so you may recognize it. deduction is reasoning from general to specific begins with an assumption—a generalization that is generally accepted as true—and moves to a specific conclusion. As noted, the formal structure of deduction is called a syllogism: 1. Major premise (MP) = general assumption about an entire group 2. Minor premise (mp) = linking statement about an individual within that group 3. Conclusion = based on logical movement from MP to mp, conclusion makes a new statement about the individual mentioned in the minor premise. Example: Major premise: All men are mortal. Minor premise: Socrates is a man. Conclusion: Socrates is mortal. Notice that we could assign a letter to represent each part of these statements: A=men; B=mortal; C=Socrates. The syllogism could then be represented as a set of mathematical equations: MP: A=B mp: C=A Conclusion: C=B If the major and minor premises and conclusion fit this pattern of A=B, C=A, C=B, the syllogism is said to be valid. However, being valid is not the same as being true. The truth of a syllogism depends on the truth of the major and minor premises. The validity of a syllogism depends on its following a prescribed format. A syllogism may be valid, but not true, if either of the premises is not true. Example: Major premise: Everyone who reads the assignment will pass the quiz. Minor premise: Jade read the assignment. Conclusion: Jade will pass the quiz. Explanation: This syllogism is valid because A=B, C=A, C=B. However, the major premise or the minor premise may not be true. For example, someone who has read the assignment but misunderstood the material or failed to remember the items the instructor found important might fail a quiz over the assignment. These facts make the major premise false. Thus, the syllogism is false. In the same way, if Jade did not read the assignment as stated in the minor premise, the minor premise would be false and, as a result, the entire syllogism would be false. More Good Examples of Syllogisms: MP: All dinosaurs are now extinct. GM makes reliable cars. mp: T-Rex was a dinosaur. Grand Prix is a GM model. Conclusion: T-Rex is now extinct. Grand Prix is a reliable car. Faulty syllogisms: MP: All dinosaurs are now extinct mp: The passenger pigeon is extinct Conclusion: The passenger pigeon was a dinosaur. GM makes reliable cars PT Cruiser is a GM model PT Cruiser is a reliable car (This doesn’t fit A=B, C=A, C=B form) (This is valid, but not true because mp is false.) Flaws that may occur in deductive arguments: One of the premises may be false Minor premise or conclusion may reverse the "if. . .then" relationship implied in the major premise, making the conclusion false or illogical Example: Major premise: Everyone who commits plagiarism must appear before the Standards Committee. Minor premise: Jeff Doe, president of the Student Senate, appeared before the Standards Committee. Conclusion: Jeff must have committed plagiarism. Explanation: Notice that the format of this syllogism is A=B, C=B, C=A. The sequence of the latter two items is reversed, making the syllogism invalid and probably false. (Plagiarists are not the only people who appear before the Standards Committee.) Vine/Hemer Argument/Persuasion Concepts English106 Have you ever noticed that when you research both sides of a question, you find yourself being convinced first by one side, and then by the other? Each argument sounds good—at least while you are reading it. When you read an argument which takes an opposite position, that sounds good too, and soon you may feel completely confused. 3 Components of a Rhetorical Situation 2. Writer (1. Expressive Focus) 1. Purpose (See parenthetical note at each point of the triangle) 3. Subject (1. Informative Focus) 4. Reader (1. Persuasive Focus) Argumentative writing has a different focus than expressive writing (autobiography, journals) or informative writing (profiles, reports, instructions) that you did in Composition I. In argument, the emphasis is on the reader or audience. Of course, your subject matter and your ideas are important too, or you’d have no reason to write, but you should be aware of the stronger focus on audience in persuasive writing. Your focus is to gain a response from your reader, so you must approach with an appropriate attitude: Writer’s relationship to audience in persuasion: I. Respect them A. Even if they’re less knowledgeable than you are B. Even if they hold a viewpoint that is completely counter to yours or that you find repugnant or illinformed. Assume that they are doing the best they can with the information or background that they have. II. Consider what you want from them A. You want them to form an opinion 1. First opinion 2. Replacement opinion B. You want them to act on the opinion 1. In their own way 2. In a way which you desire or present III. Consider what they know of the subject A. Nothing: explain clearly B. Misinformation: respectfully correct them and clarify points C. As much as you do: move to attitude IV. Consider their current attitude A. Supportive: emphasize emotional appeal to reinforce their commitment/rouse their desire to act B. Neutral or wavering: emphasize logical appeal to establish validity and importance of your point; emphasize your credibility to strengthen their response C. Apathetic or hostile: apathetic may be most difficult audience to deal with because you must gain their interest before you can move them with logic or values: emphasize logic, values, credibility. As you analyze your audience, establish these qualities of your writing: 1. Your voice as writer Are you an expert writing to amateurs? Are you a sincere and concerned individual citizen? Are you an equal of your audience, asking their attention for a personal concern? Vine/Hemer Argument/Persuasion Concepts English106 2. Your relationship or credibility with your readers Show your experience with the subject Offer quality research Be fair 4 Be logical Choose words precisely Build common ground 3. Your tone with regard to the subject Choices: Being reasonable, firm, distant, sarcastic, ironic, urgent, humorous, moral, weary, chiding, sporting a “we’re in this together” camaraderie, full of righteous indignation Good tone choices Bad tone choices Consider which tone will do most to accomplish your chosen purpose. Writer’s Task in Argument In Argumentative or Persuasive writing, you must make sense of information, prove your thesis, and convince your audience. Start by deciding which ideas are important to your position/which are not. Main Ideas and Supporting Details One needs to be able to locate the important points, so place them At the beginning of your selection As topic sentences for each paragraph Repeated throughout the essay in various ways Also emphasize important points in the following ways: Use transition words, phrases, idea markers o o “the point is” this is one reason” o o The causes are complex” “In contrast” Identify supporting information by using markers o “for example” o “to illustrate the point” Follow a plan for the organization of your essay (cause-effect, compare-contrast the similarities and differences, build to most important point, etc.) Separating Facts from Opinion Fact: a statement that can be proven true or false. Your argument gains credibility if supported by facts: Consult reliable sources Quote experts Opinion: personal belief that cannot be proven true or false Signal words can indicate your opinion (feel, think, doubt, agree, would argue, etc.). Do not use: “In my opinion,” “I believe,” or “I think.” Going Beyond the Facts In reading or writing argumentative essays, you must use the information by thinking about what you already know; then you need to make inferences, draw conclusions, or make generalizations. Inference: logical guess one makes by combining what you learn with your prior knowledge Drawing a conclusion: a judgment or decision. It is based upon facts, inferences, and prior knowledge. Generalization: A broad idea or statement based on specific examples. Avoiding Errors in Reasoning Argumentative reading and writing are meant to persuade you to buy (Evaluation), believe (Position) or do something (Proposal). Before you make decisions or take action, use critical thinking to look for errors. Becoming aware of these errors will help you avoid them in your own writing. (See Propaganda Techniques section of the handout). Vine/Hemer Argument/Persuasion Concepts English106 5 Recognizing Emotional Appeals Emotional appeals are statements directed at people’s emotions rather than their sense of reason. There is nothing wrong with appealing to emotions if the argument is based on logic and values as well. However, the following strategies may be used to create faulty persuasive writing: Loaded language: Use of words that have strong positive or negative associations. If reading makes you angry, enthusiastic, afraid, etc., the essay probably contains loaded language. Emotional fallacies: Some emotional appeals are not valid tools of argument. These “emotional fallacies” attempt to play on the audience’s emotions IN PLACE OF providing a supported and reasoned argument. Flattering and threatening the audience are examples of such fallacies. See Emotional Fallacies section of this handout for more information. Hemer & Vine’s List of 11 Propaganda Techniques Propaganda: techniques used to persuade people to accept an idea or cause, good or bad. Propaganda is used for a variety of reasons, including politics, advertising, and fundraising. Know definitions for each term, as they will be on quizzes and tests. 1. Name calling—calling other people bad names, negative words. Ex: “My lazy opponent is running our country into the ground!” 2. Arguentum ad hominem—a Latin term for “argument to the man.” While name calling directly attacks another individual, argumentum ad hominem distracts attention away from the issue with irrelevant, offtopic slurs of the person. Ex: “My opponent smoked marijuana when he was in college.” What does that have to do with the way he works in office now? 3. 4. 5. 6. Glittering generalities—vague words with positive connotations. Ex: “As candidate for office, I believe in the American way.” It sounds good, but there is no exact definition for “American way.” Other examples: “justice,” “freedom,” “Constitutional rights,” and “family values.” Are these just glittery words to distract our attention? What specific details are included to add substance to the appeal? Slippery slope—a dire chain of events unlikely to occur. Ex: “If my opponent takes office, he will raise taxes, ruin the economy, and cause unemployment to skyrocket. Before you know it, everyone in this country will be broke, out on the streets, and in bread lines.” Is such a chain of events likely to happen, or is the speaker exaggerating? Hasty generalization—reaching a conclusion based on insufficient evidence/an isolated example. Ex: “I took anti-depressants for my depression, and just got worse. Clearly, drugs are being used too often to treat mental illness.” Does the speaker offer enough examples or evidence in addition to personal experience to support the claim? Transfer (guilt or glory by association)—know both transfers: Guilt by association—transferring our dislike or disapproval of an idea or group to another idea or group that the speaker wants us to criticize and reject. Ex: “My opponent’s attempts to make us accept his idea sounds suspiciously like what happened in Germany in the 1930’s. By the way, have you ever noticed how his mustache resembles Hitler’s?” Is the comparison fair or accurate? Glory by association—transferring positive feelings of something respected and loved to an idea or group the speaker wants us to accept. Ex: “This plan will succeed, just like our Olympic athletes brought home the gold last year.” 7. Bandwagon—persuading others to join a cause or do something because everyone else is, because it’s popular. Ex: “Join the rest of the district in supporting Smith for Congress.” Does joining everyone make it a good idea? 8. Testimonial or endorsement—a respected or loved person giving a statement of support. Ex: A popular celebrity might endorse a candidate for office or a respected politician might endorse a fundraising organization in attempts to raise more money. Advertising frequently uses this technique: “Michael Jordan wears Hanes for Men; so should you.” People should think about whether the person is an authority on the issue or product before accepting his or her testimonial as reasonable. 9. Faulty cause and effect (sometimes called by the Latin terms post hoc and non sequitur)—a cause and effect relationship that might not be true. Ex: “When I took office, the unemployment rate dropped to three percent.” Listeners should question whether the rate dropped because of the person in office, or because of other factors beyond the person’s control. Did that person actually cause the rate to drop? Just because one event follows another does not mean that the first caused the second. What evidence supports the causal relationship? Vine/Hemer Argument/Persuasion Concepts English106 10. Two extremes fallacy—portraying or viewing reality in sets of two extremes, or polar opposites. Ex: 6 “America: love it or leave it.” “A person is either for capitalism or she is for communism.” While the speaker or writer tries to portray the issues as a matter of black and white, listeners or readers should also look for gray areas or other points of view. 11. Straw person—distorting an opponent’s view so that it is easy to attack; thus, the argument attacks a point of view that does not truly exist. Emotional Fallacies From San Jose State University's "Mission: Critical" Website http://www.sjsu.edu/depts/itl/graphics/adhom/emotion/html (Try connecting with the site using this part of the URL: http://www.sjsu.edu/depts/itl Fallacious emotional appeals all have two things in common: 1. They attempt to elicit an emotional response that will serve as the basis of any decision made instead of presenting an argument and relying on its soundness. 2. As a result, they are never acceptable in an argument, though they can be quite effective in arousing nonrational responses. 3. Fallacious appeals to emotion are effective because it's easier for most people not to think critically, but to rely on their gut reaction; and it's easier for the person making the appeal to excite his listeners' emotions than to construct a persuasive argument. As a result, those who try to persuade us most often—politicians and advertisers—tend to rely on emotional appeals in order to motivate us to do things that we might not do for purely rational reasons. 4. Fallacious appeals can target almost any emotion, but some are more common than others. In this section, we will be focusing on five different appeals: to fear, loyalty, pity, prejudice, and vanity. Appeal to Fear: Fear and love are two of the strongest emotions, and this sort of non-rational persuasion is usually designed to tap into both of them, by threatening the safety or happiness of ourselves or someone we love. As a result, it's often called scare tactics or appeal to force because the threats of force are intended to scare us into agreement or action. Consider the following appeals: "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but if you give me a ticket, I'll have to call my friend the mayor and have a long talk." Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but if you give me a ticket, you better make sure your family is in a really safe place." Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but if you even start to give me a ticket, I'm going to shoot you with this gun." Notice that the first threat is the most veiled, carried in the implication that the speaker has a powerful friend that can adversely affect the officer's career. The second threat is also veiled--the speaker never says he or she will do anything, and in some situations, advice to ensure the safety of one's family might be considered downright neighborly. But the second appeal is, in other ways, more powerful than the first, because it threatens the officer's family with violence. The threat in the third example is so direct—the speaker has apparently pulled a gun on the officer—that it might not be considered a fallacy at all. Certainly, caution would be the best response in each of these cases, but most of the threats encountered in critical thinking are less direct and less violent than these examples. Remember that, while all appeals to fear involve negative outcomes, not all negative outcomes necessarily derive from fallacies. When the doctor tells you to change your diet or you'll die young, and when the dentist tells you to floss better or you will lose your teeth, they are probably not engaging in a fallacious appeal to fear. Instead, they are explaining to you the demonstrable consequences of your actions, not as a threat but as information upon which they hope you will act. Appeal to Loyalty: since humans are social beings, one of our strongest emotions involves attachment to the group, and there are several different ways to appeal to that emotion. One is the general appeal to loyalty, which operates on the notion that one should act in concert with (what is claimed to be) the group's best interests, regardless of the merits of the particular case being argued. Chauvinistic slogans, like "My country, right or wrong," are good examples of this sort of non-rational emotionalism, and Vine/Hemer Argument/Persuasion Concepts English106 such appeals are often known as ad populum arguments, meaning that they are directed "to the people." Fallacious use of peer pressure and bandwagon are other variations on the appeal to loyalty. 7 "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but we cops have to stick together." (Apparently this statement is being made by an off-duty officer who has been stopped.) "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but you've got to get with the program. Everyone else lets other cops off with just a warning." The first appeal to "stick together" rather than judging the case on its merits shows how appeal to loyalty works. The second example illustrates bandwagon—doing something just because everyone is doing it, regardless of whether it is proper. Appeal to Pity: A fallacious appeal to pity, also known as a sob story, is different from a simple (and perfectly legitimate) appeal to pity in one significant way: it is used to replace logic rather than to support it. As far as critical thinking goes, it would be perfectly legitimate for someone to say, "Please give me some money to buy food. I haven't eaten in days." Certainly, this would be an appeal to pity, but as long as the appeal is made in such a way as not to interfere with logical consideration of the situation (such as whether the request is appropriate for the problem, whether you can reasonably afford or provide what is requested, and so on), it need not be fallacious. When the fallacy does occur, it usually exhibits either a greatly exaggerated problem or an inappropriate request. Most of all, a fallacious appeal to pity uses emotion in place of reason to persuade. For example: "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but please don't give me a ticket. If you do, they'll suspend my license, I'll lose my insurance, I won't be able to work, and my kids will go hungry." Note that this is a "slippery slope sob story." **One item of note about the appeal to pity, fallacious or not, is that it often fails, because the emotion is mostly on the side of the one making the argument. If readers see the argument as a desire to be pitied, many will turn off their emotions rather than respond from them. Often a dispassionate but accurate account of one's plight is more effective than a tear-filled narrative of the wrongs one has suffered. Appeal to Prejudice: A prejudiced response judges groups of people or things either positively or negatively, even after the facts of the case indicate otherwise. By appealing to prejudice in the reader, the person making the argument attempts to ensure a favorable reaction to his or her argument. Often such an appeal works on negative images, but some appeals to prejudice do not carry the hatred necessary for another emotional fallacy—appeal to spite. Consider this example: "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but there ought to be special laws for those of us proud to be American and driving American-made cars on our streets, instead of making us follow the same rules as those foreign-made cars that have ruined the economy and put so many good Americans out of work." This statement could be made without hatred, but perhaps it requires some indignation. In any case, the speaker has mixed prejudice with wishful thinking to produce an image of how the world would be if people with a prejudice against foreign-made cars were in control. Appeal to Vanity: Also known as apple-polishing, the strategy behind this fallacy is to create a predisposition to agreement by paying compliments. The success of the strategy depends on a combination of the vanity of the target and the subtlety of the compliment. It is usually more effective when the compliment is somehow related to the situation at hand: "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but it certainly was perceptive of you to notice. You deserve a commendation."