China-1-Midterm - Georgia Political Review

advertisement

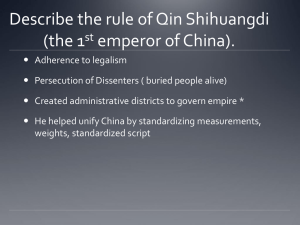

Chet Martin Dr. Ari Levine It’s October 3 China 1 Midterm ID Polycentric Hypothesis: The idea that Chinese civilization did not spread from one cultural hearth in the period from pre-history to roughly 1000 BCE but multiple, in areas ranging from the Shang that have traditionally been seen as the creators of “China” in the Yellow River Plain in north China to other areas like the people of the Sichuan River Valley and the southeastern coast, including Taiwan/Formosa. Scholars estimate that there were as many as a dozen Chinese hearths. While the Oracle Bones of early Chinese script from the Shang region in the North China Plain bolstered the argument for the “Nuclear Hypothesis”, other archeological finds like the tamped earth walls found to the West of the Shang and Shang reports of a powerful foreign state in the southern Sichuan region indicate that multiple regions of “China” created complex, organized societies. Scholars maintain that the presence of unusual goods in archeological sites (sea shells far inland, for example) proves that these people were in contact, often fighting, trading, and exchanging cultural norms Impartial Caring: The central tenant of Mozi, who lived in the Warring States period from approximately 400 to 350 BCE. Impartial Caring was created in opposition to the tenants of Confucianism; while Confucius argued for a system of morality predicated on appropriate bonds of fealty to superiors, notably within the family, Mozi argued instead for a morality system that demanded everyone treat each other with a certain degree of decency so that we can all be excellent to each other. Often mistranslated as “Universal Love”, Impartial Caring is a kind of utilitarianism that argues that the Jean Val-Jean scenario (man steals a loaf of bread for his starving family) is an example of evil, and that this invalidates Confucian thought. These beliefs fell out of favor as the Qin and Han took over China and established Confucianism (in broadest possible strokes) as state policy Hegemon system: The means by which the Zhou ruler appointed the strongest of the central state kings (or dukes, at the time) as chief among his peers during the Spring and Autumn Period of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (roughly from 700 BCE to 500 BCE.) The strongest of the five major nations that ruled the land that had once been controlled by the Zhou, the Hegemon (“Ba”) was tasked with keeping the peace among his neighbors and enforcing a code of morality among rulers that stemmed ultimately from the Zhou lineage law system. One of the greatest of the Hegemons was “Double Ears” of Jin. While not emperor or ruler of the other states, the Hegemon was a sort of “chief among equals” as the Eastern Zhou struggled to maintain order before the bloodier and messier Warring States period. Xiongnu: The nomadic people living in areas north of China who threatened the Han Dynasty from roughly 200 BCE to 100 BCE. The Xiongnu defeated an army of the first Han Emperor Gaozu and forced the Han to pay tribute and acknowledge the Xiongnu as a “sister nation” whose ruler was of the same stature as the “Huangdi.” The war to defeat the Xiongnu in the third century BCE facilitated the creation of a massive Chinese military and increasing demand for taxation, as well as bringing the Han in contact with many of the peoples of central Asia. The eventual defeat of the Xiongu around the tinme of the Emperor Wu allowed the Emperor to focus on conquering the eastern kingdoms and made the Han Empire safe from existential outside threats. Sima Qian: The Court Historian and author of “Annals of the Grand Historian” around the time of Emperor Wu in 150 BCE. Sima Qian wrote the first comprehensive account of “Chinese” history that mentioned the independent motivations of historical actors. He wrote with much independence and venerated the ancient Zhou dynasty and approved of their concept of “Mandate of Heaven” by condemning the last king of the Shang; similarly, he condemned the reign of the Qin as violent and oppressive. His book is the best source we have on much of pre-Han Chinese history and can be considered the “first draft” of that history Wang Mang: A minister for the Han Dynasty that usurped the throne in 9 CE and established the “New” (Xin) Dynasty. Wang Mang venerated the ancient Zhou dynasty and forbade the purchase of land and redistrusted land to the peasants in an effort to check the power of the aristocratic families of the Han. Ecological disasters (including a massive river flooding) and the antipathy of the disempowered nobles did him, and his “dynasty” survived less than twenty years. Nevertheless, Wang Mang’s usurpation led to the establishment of the Han capital in Luoyang and the beginning of what is called the “Eastern Han” period; the Han Empire never quite recovered from this episode Limited Time Frame Emperor Gaozu’s conquest of the Qin Empire around 200 BCE and the “confederation” system that took its place was a slow and complicated process involving many smaller states, peasant armies, and many of the nobles that had been deposed and weakened by the Qin Empire. As a commoner without a strong attachment to regional identity (he was born, worked, and ruled in different parts of China), his power was diffuse and contingent upon the continued support of the nobles and generals who had propelled him in to power. At the foundation of the Han regime, he declared legal simplicity that undercut the rigidly structured Legalist state of Qin; he was promising his followers that he would not be as oppressive or powerful as they viewed the Qin dynasty to have been. He quickly divided his empire into a western “half” (more like a third) centered around the capital and ruled directly by the emperor and eastern kingdoms that were ruled by his supporters (mostly his kin.) Gaozu split his empire so that he wouldn’t be vulnerable to as many opposition forces as the Qin. After Gaozu’s death, the reign of Empress Lu (at the cost of multiple infant emperors for which she was “regent”) and the attack of the Xiongnu made it difficult for the Han state to establish centralized power. Lu’s death around 170 BCE was followed by the massacre of her family and a wariness among court officials to allow any political actors to become strong enough to rule as she had (the families of consorts were especially untrusted.) Likewise, the series of weak emperors that followed Empress Lu would have been incapable of staging an attack on their eastern kin as they were preoccupied with the Xiongu threat and needed their support to face them. It was the defeat of the Xiongnu, which occurred only after the Han Emperors recruited stellar meritocratic generals, adopted cavalry tactics, and raised armies of hundreds of thousands, that gave the Han the breathing room to take on their Eastern cousins. It was in to this world that the Emperor Wu was born around 150 BCE. With the Xiongnu defeated, Emperor Wu had fewer institutional restraint than any Chinese leader before him. When a rebellion by the king of the southeastern coast (whose son Emperor Wu was responsible for killing) was joined by other powerful Eastern kingdoms, the bureaucratic Emperor Wu, who forbade eastern bureaucrats from joining his service and made passage between the two Han zones possible only with special passports, took his opportunity to lay low the rebellious East. Motivated by court ministers (from the Confucian Academy he founded) that stressed fealty to emperor and declared him the upholder of the cosmos, Wu defeated the eastern kings and spread his bureaucratic, nominally meritocratic way of rule to the Eastern kingdoms. In the consolidation of imperial power (Wu’s bureaucrats could only make policy by submitting memoranda to be approved by the Emperor), the increased support for Confucianism, and the beginning of the civil service exam, Wu can be considered nearly a co-founder of the Han regime. Extended Time Frame If Warring States thinkers agreed on anything, it was that the world in which they lived was troubled. The Warring States Period (roughly 500 BCE to 237 BCE) was characterized by near-constant warfare between the central states and the breakdown of the hegemon (“Ba”) system that gave nominal control to the Zhou ruler and true control to the strongest of the central states. Much of Warring State thought was a series of reactions to Confucius, whose life straddled the line between the Spring and Autumn Period and the beginning of the Warring States. Confucius was the first of many thinkers of the Shi class, a group of upper middle-class intellectuals (made up mostly of degraded Zhou nobles as well as elevated commoners) who were literate and educated without ruling anything of their own. This class (hereafter “gentleman”, the closest Western translation to the term) was the Chinese incarnation of “Axial” thinkers, who began teaching students at a price and having those students pass down their teaching orally, which became a written document centuries later, much like Socrates or Buddha. The presence of these gentleman, educated enough to examine the past but lowly enough to be without the responsibilities and challenges of ruling, in the fluid social strata of the Warring States period allowed the philosophizing and didactic argument that led to the formation of multiple schools of Chinese thought. Likewise, the presence of many states in which to work and teach prevented the formation of a heterodoxy of thought; rulers could not stamp out ideas in all of China, and thinkers who found themselves unwelcome in one kingdom could make a new home in another. Finally, the existential threat that all central states constantly existed in denied rulers the luxury of ridding themselves of a single turbulent thinker; rulers needed those who were most capable to validate and strengthen their rule. Above all else, Confucius and those who followed him venerated the earlier periods of Western Zhou rule. They disagreed mightily on the moral system that could replicate the relative peace and harmony of that time. Confucius and Mozi both believed that the rulers of the current world were wicked, but refused the idea that gentleman should withdraw from that world in order to save themselves from the wickedness, a view expounded by early Daoist thinkers. Writings attributed to Confucius (but almost certainly not written by him) in the Spring and Autumn Annals praise the earlier days of the Zhou dynasty before the Warring States period. Where Confucius argued in the Analects that society could be held together by rigid adherence to five key relationships (especially the relationship between parent and child), Mozi, who lived immediately after Confucius, took positions contrary to his master and stressed in his commentary on the Analects that society required “impartial caring”, a kind of Utilitarianism, between all humans to return to the glory day of the Zhou; he took great offense to the ostentatious funerals demanded by Confucius, saying that such lavish praise of authorities was little more than conspicuous consumption, not a moral necessity. Confucian thinking eventually won out with the end of the Warring States period and the institutionalization of his thought under the Han; his rigid theories made rule much easier in the years following the Warring States period, especially his belief that the relationship between ruler and subject should mirror the parent child relationship. Later Warring States thinkers like Mencius pondered human nature, and how the state should be structured because of that nature. Mencius argued that humanity was essentially good and that a corrupt world had brought man down, while rival thinkers of his age (especially the misspelled Xunzi) thought that human beings were corrupt and that only the institution of government and society could save them from their wickedness. Both thinkers agreed that the nature of government must stem from the nature of man, but differed wildly in that interpretation. It was the rigid order argued for by Mencius’s rival that triumphed in the Qin Dynasty and contributed to their legalistic theories and reorganization at the hands of the powerful minister Shang, a sort of Warring States Bismarck. This was almost commonplace in Warring States China; Confucius, Mozi, and Mencius were arguing over how a proper society should be governed (in clear reaction to the perceived inadequacy of governance in their lifetime) and lobbied for their teachings to be adopted by states so that those states may gain an advantage over their rivals. All three were concerned with the disunity of the time and hoped that a well-governed state (one that adopted their teachings, naturally) would defeat the others, unify “China”, and bring it back to previous Zhou harmony.